EQカーブの歴史、ディスク録音の歴史を学ぶ本シリーズ。前回 Pt.8 では、1942年に策定された、放送局用トランスクリプション盤向けの録音・再生標準規格、通称「NABカーブ」についての歴史を調べました。

On the previous part 8, I studied on the history and background of “1942 NAB Curve”, the first recording/reproducing standards for electrical transcription discs used in the broadcasting industry.

今回はその続きで、第二次世界大戦中〜LP登場前夜のあれこれ をみていくことにしましょう。市販のシェラック盤への不満が徐々に蓄積されていたことを示す記事や、EQカーブが当時どのように捉えられていたか、がうかがえる資料などです。つまり「何が正解か」ではなく、「当時はどう考えられていたか」の探求です。

This time, I am going to continue learning the history of disc recording – during the WWII, as well as post-WWII period, until the advent of microgroove LP records. This include growing discontent with the quality and experience with commercial shellac records, as well as how listeners and engineers tried to deal with “EQ curves” in these years. So this article is the exploration of “how the things were regarded at that time”, not of “what is the correct answer”.

ただし、当時の技術書類やエンジニアノートなど、一次資料が非常に少ないトピックが多くなるので、当時の雑誌ではどのように言及されていたか、など、間接的な探求が多くなることをご理解の上、ご覧ください。

Please note that this article contains the topics whose primary information (such as technical documentation and engineers’ notes) is rarely found, and I am going to read many magazine articles about the topics, to understand the situation of the 1940s indirectly.

source: NAB Reports, January 2, 1942, Vol.10, No.1, p.1

- 「Pt.0 (はじめに)」

- 「Pt.1 (定速度と定振幅、電気録音黎明期)」

- 「Pt.2 (世界初の電気録音、Brunswick Light-ray、ラジオ業界の脅威)」

- 「Pt.3 (Blumlein システム、当時のRCAやColumbia、民生用における高域プリファレンスの萌芽)」

- 「Pt.4 (Vitaphone、Program Transcription、Electrical Transcription、Bell Labs / Western Electric 縦振動トランスクリプション盤)」

- 「Pt.5 (ベル研とストコフスキーのエピソード、横振動トランスクリプション、Orthacousticカーブ)」

- 「Pt.6 (アセテート録音機のカッターヘッド特性、高調波歪の論文、超軽量ピックアップ)」

- 「Pt.7 (圧電ピックアップとジュークボックス、定速度記録再生の試み)」

- 「Pt.8 (1942年 NAB 標準規格策定の歴史)」

の続きです。

This article is a sequel to

- “Things I learned on Phono EQ curves, Pt.0 (Intro)”,

- “Pt.1 (constant velocity/amplitude, early years of electrical disc recording)”,

- “Pt.2 (earliest electrical recordings, Brunswick Light-ray, Radio industry)”,

- “Pt.3 (Blumlein system, RCA and Columbia in the early 1930s, germination of treble pre-emphasis)”,

- “Pt.4 (Vitaphone, Program Transcription, Electrical Transcriptions, Bell/WE Vertical Transcription)”,

- “Pt.5 (Bell Labs = Stokowski episode, Lateral Transcription and Orthacoustic)”,

- “Pt.6 (Instantaneous Recorders, papers on distortion and lightweight pickup)”,

- “Pt.7 (piezo-electric pickups, jukebox, constant-amplitude recording)”,

- and “Pt.8 (history of 1942 NAB Standards)”.

毎回書いている通り、筆者自身の学習過程を記したものですので、間違いの指摘や異論は遠慮なくお寄せください。

As I noted in every part of my article, this is a series of the footsteps of my own learning process, so please let me know if you find any mistakes on my article(s) / if you have different opinions.

今回も相当長い文章になってしまいましたので、さきに要約を掲載します。同じ内容は最後の まとめ にも掲載しています。

Again, this article become very lengthy – so here is the summary of this article (the same contents are avilable also in the the summary subsection).

シェラック盤という材質に由来するサーフェスノイズの多さの問題は、1940年代当時も十分に認識されていた。そのサーフェスノイズを再生時に軽減するべく、トーンコントロールにより高域減衰して「聴きやすさ」を優先させることが、当時の標準的な技術トレンドであった。

High amount of surface noise, originated from the nature of shellac compound, was recognized in the 1940s. In order to cope with surface noise, utilization of “tone-control” during the playback was the standard technical trend at the time.

ユーザにより高域減衰されることを見越して、多くのレコード製造側が録音時に高域増幅(プリエンファシス)して記録し始めていた。しかし、1940年代の市販用シェラック78rpmレコード向けにどのようなプリエンファシスが具体的に施されていたのか、については、当時の資料にもほとんど記録がなく、参考資料がほとんど残っていない。家庭用市販レコードにおける正確なプリエンファシスや録音カーブの議論は、戦後の再生機器の技術向上とマイクログルーヴLPの登場を待つしかなかった。

Many record manufacturers started to use high-frequency pre-emphasis during the recording (cutting) to compensate the high frequency attenuation conducted by listeners. However, few articles and papers concretely describe the exact parameters and circuits used for cutting commercial shellac 78rpm records; virtually no engineers’ documentation survives (surfaced). After all, a few more years were needed for detailed discussion on pre-emphasis and recording / reproducing curves for commercial home records, until the development of higher-quality reproducing instruments as well as the advent of microgroove LP records.

主に市販用クラシック盤において、思い思いにターンオーバー周波数を上げ、記録可能なダイナミックレンジをあげようとする技術者間の競争のようなものがあった。一方、ダンスミュージック(ジャズやポピュラー)は、ジュークボックスの普及もあり、そのような「公開実験」のような試みはあまり行われていなかった、という説がある。

Primarily in the commercial classic records field, many engineers enjoyed “a friendly rivalry” in pursuit of the extension of dynamic range, by extending the turnover frequency to his/her preference. On the other hand, one critic notes in his 1944 article that dance music (jazz & pop) records never suffered from such “experimentation on the public”, probably because of the popularity of jukeboxes.

当時の市販用シェラックレコード製造側には、記録特性の標準規格化を目指す人はほとんどいなかった。一方、無秩序な現状に不満を持っていたリスナー、評論家、研究者は少なくなかった。

Manufacturers of commercial shellac records at that time rarely tried for the formulation of recording standards. On the other hand, there were non-negligible number of listeners, critics and researchers who expressed discontent with the situation in disorder.

LP以後の時代と異なり、そもそもシェラック盤での有効な記録周波数帯域上限は実質 8,000Hz 程度であった。また、当時のコンシューマの再生機器の環境や性能のばらつきもあり、どのように再生されるのが正解か、共通認識もなかった。結果、当時のリスナーもエンジニアも「カーブ補正による完全なフラット再生」など念頭になかった。

Unlike later microgroove LP records, useful frequency content in commercial shellac records were substantially limited to about 8,000Hz. Also, performance and ability of reproducing equipments of home users varied much, and there was no common recognition of how the shellac records should be played the best. As a result, few people (even engineers and manufacturers) even thought of “compensating the recording curve for full flat reproduction” at the time.

現在ではほとんど使われなくなってしまった圧電ピックアップ(クリスタルカートリッジ / セラミックカートリッジ、本稿 Pt.7 参照)だが、1940年代には、家庭用機器を中心としてほとんどのシェアを獲得していた。出力が大きく、フォノイコも簡略化でき、安価であることがその理由であった。プロフェッショナル市場においても、より高性能なマグネットカートリッジが主流ではあったが、一部で圧電ピックアップが使われていた。

Piezo-electric pickups (crystal and ceramic, see Pt.7 of my article for details), although virtually disappeared in the present era, were very popular and acquiring top market share in the 1940s, especially in the home instrument market. It was particularly because of the high voltage output, requiring simplified compensation circuits, and being inexpensive. Piezo-electric pickups were also used moderately in the broadcastinc indstry, although high-quality magnetic pickups were the main force there.

一方、本稿 Pt.4、Pt.5、Pt.8 でみてきたように、放送局用にはヴィニライト製でサーフェスノイズが少なく、1942年に標準規格化もされており、フラットな録音再生がほぼ実現できている、トランスクリプション盤がすでに存在していることが、放送局外の人々にも知られていた。

On the other hand, people outside the broadcasting industry already knew that there existed “Electrical Transcription” in the professional field – made of vinylite, quieter surface, recording and reproducing characteristic already standardized in 1942, nearly flat / uniform reproduction being feasible, as we have already seen in the Pt.4, Pt.5, and Pt.8 of my entire article.

当時の市販用電蓄には当然再生EQカーブ選択はなく、サーフェスノイズ対策の高域減衰をトーンコントロールで思い思いに調整していた。プロ用(放送局用)でも、再生フォノイコ部分は、基本は当時の標準規格とフラットのセレクトで、追加で主にサーフェスノイズ対策や摩耗した盤用の高域減衰量セレクトが選べる程度だった。

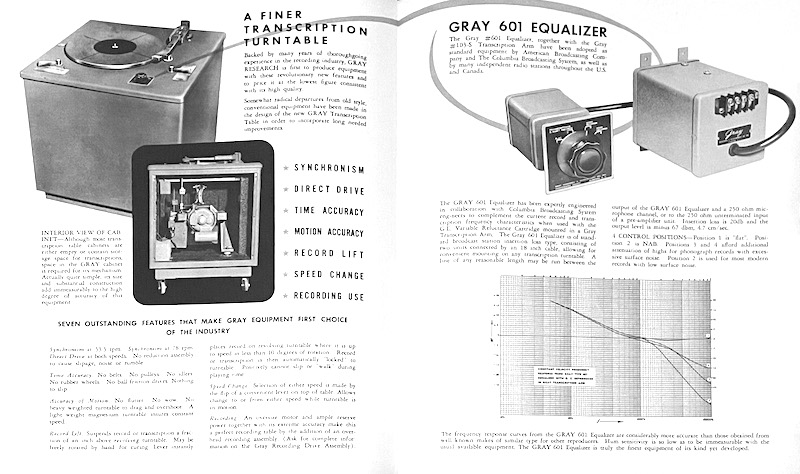

Home phonograph players at the time didn’t have variable EQ selectors: listeners used tone-control feature to attenuate high-frequencies to reduce surface noise. On the other hand in the professional field, transcription turntables were equipped with selectable phono equalizers, although it can switch the position among the followings: flat above 500Hz; standard curve (at the time); and several others with different amount of high-frequency attenuation (to cope with surface noise or worn records).

Contents / 目次

- 9.1 WWII Halts Phonograph Development / 第二次世界大戦で開発が足踏み

- 9.2 Some implications found in 1940s’ articles / 1940年代の各種記事から読み取れること

- 9.2.1 “Looking Ahead”, D.J. Julian, American Music Lover, July 1944

- 9.2.2 “MORE RECORD DATA, PLEASE”, Audio Engineering, November 1947

- 9.2.3 “Future of the Disc”, Wireless World (UK), January 1944

- 9.2.4 “Report of Technical Session at Gramophone Conference”, 1939

- 9.2.5 “Crystal Pickup Compensation Circuits”, Electronics, November 1945,

- 9.2.6 “Practical Disc Recording”, 1948

- 9.3 Some Implications found in 1940s’ equipments / 1940年代の各種機器から読み取れること

- 9.4 The summary of what I got this time / 自分なりのまとめ

9.1 WWII Halts Phonograph Development / 第二次世界大戦で開発が足踏み

1939年9月のポーランド侵攻、1941年6月の独ソ戦争、1941年12月の太平洋戦争と、時代は第二次世界大戦に入っていきます。結果として、多くの研究開発リソースが軍事開発に向けられることとなり、プロフェッショナル向け・市販向けを問わず、レコード録音再生技術の開発・発展は一時足踏みすることになります。

The invasion of Poland from October 1939; The Eastern Front conflict from June 1941; Asia-Pacific War from December 1941 – the whole world entered the World War II. As a result, many research/development resources were applied to war research and military development, resulting in a halt of the development and the evolution of disc recording and reproducing.

本稿 Pt.6 でも紹介した、超軽量ピックアップ発明者の F.V. Hunt 氏のインタビューにも、このような述懐がありました。

As I quoted in the part 6 of my article, oral interview of F.V. Hunt (inventor of ultra-light phono pickups) included the following lines as he revealed:

And the reason I mention this is that this is the fortune that Jack and I eschewed and gave up to the phonograph industry because we both got distracted by war research, the patent came out during the war, and by the time the war was over it had already been late, we had abandoned it, we never sued anybody. If we had been careful about picking some small fellow and suing him and getting the claims validated, I think we could probably have made a lot of money from the side wall support, because by the time the war was over everybody took it for granted that, of course, the stylus was supported on the side walls of the groove, how else would you do it? And without realizing that—in 1938—this was not only novel but no other pickup could do it except our experimental job. (…)

なぜ今この話をしているか、というと、Jack (Pierce) と私の2人は当時戦時研究に追われていたため、蓄音機業界に見切りをつけた、そういう運命だったからだ。HP6Aピックアップの特許は第二次大戦中に発行されたが、戦後にはすでに遅きに失していたため、我々はその特許を放棄し、誰も訴えることはなかった。戦争が終わった頃には、再生針は音溝の側壁でサポートされているのは当たり前のことだ、と誰もが思っていたから、もしも我々が当時、側壁サポートに関する我々の特許を侵害している、と訴えを起こしていたら、その特許で大金を稼ぐことができていたであろう。実際には、再生針の音溝側壁サポートは、(我々が特許を申請した当時の)1938年においては斬新であっただけでなく、我々による実験的な開発によって生んだ HP6A ピックアップ以外では不可能なことであった。 (…)

Oral History Interview: Frederick Hunt - Session II (interviewed by Leo Beranek and Charles Weiner), January 8, 1965 at Harvard Universityましてや、1942年7月31日〜1944年11月11日という長期間に渡った、有名な レコーディングストライキ もありました。それには、レコードの原材料となるシェラックの輸入が大戦によって滞り、さらには録音原盤に使うアルミニウムの枯渇など、戦時ならではの事情も絡んでいました。

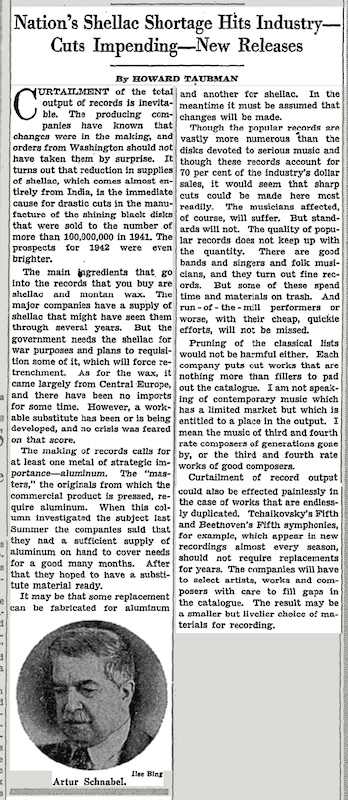

Furthremore, the musicians’ union called a ban on all commercial recordings, which later known as 1942-1944 Musician’s Stroike (“Petrillo Ban”). Shortage of Shellac (ingredient of 78rpm discs) and alminium (used for wax/lacquer masters) was also the issue during the war, and was related to the ban as well.

source: “Nation’s Shellac Shortage Hits Industry – Cuts Impending – New Releases.”, Howard Taubman, The New York Times, April 19, 1942, p.186.

レコード製造に必要なシェラックとアルミニウム版の不足を伝える記事

そして 前回 Pt.8 でみてきたように、よくぞこのような国を挙げての非常時である1941年〜1942年に、アメリカの放送局用トランスクリプション盤向けにNAB録音・再生標準規格が議論され正式に策定されたものだ、と驚かされます。

So, I am simply suprised by the fact that, National Association of Broadcasters could discuss and adopt the NAB Recording and Reproducing Standards, in such emergency period of 1941-1942, as we have seen in the part 8 of my article.

しかしそれは、(A) すでにヴィニライト製のトランスクリプション盤が一般的で、かつプロフェッショナル現場であった放送業界、(B) サーフェスノイズが多いシェラック盤が一般的で、かつアコースティック蓄音機もまだ現役であった(しかもジュークボックスでも使われていた)一般購買層向け市場、この両者の違いでもある、ということでしょう。前者の方が、より厳格な規格を求められる(そして求めることが可能だった)からです。

From a different point of view, the standardization for electrical transcriptions was possible because the transcription discs were made of vinylite (with quieter surface) and the broadcast industry was “professional”. On the other hand, commercial home disc records were made of shellac compounds exhibiting much surface noise, and the reproducing equipments at home varied from hand-wound phonograph to modern electric radio-phonograph machines. Also, shellac records were also used for jukeboxes. The “professional” field wanted more strict standardization, and they could.

そしてそれが、放送局向けの技術資料は大量に残されているのに、市販用レコード制作現場の技術資料がほとんど残っていない(あるいは非公開)である、という違いでもあるのかもしれません。

Plenty of technical documentation, papers and articles for professional disc recordings in the broadcasting industry survives, while those for commercial home records rarely survives (or were concealed behind the closed doors) – various differences between “professional” and “consumer” might be the reason for that.

9.2 Some implications found in 1940s’ articles / 1940年代の各種記事から読み取れること

この時期の事情について調べている最中に、PSPATIAL AUDIO (Stereo Lab) のサイトに非常に興味深い説明を見つけたので、ここに引用します。1930年代〜1940年代の市販レコードにおける、プリエンファシス適用に関する米国と欧州との違いについての考察です。

While I was searching and studying the history of the 1940s, I found by chance an interesting article at PSPATIAL AUDIO (Stereo Lab) web site. Below is the quote I thought interesting – an observation on the difference between the US and Europe, of the pre-emphasis applications.

Now, the idea of cutting the bass, to improve playing time, and to pre-emphasise the treble, to cut surface-noise, are both really good ideas (given certain assumptions) and more of both were gradually applied to records as the nineteen-forties progressed; especially in America. In fact, it is not a caricature to say that the main difference between pre-RIAA records from America and those from Europe in this period is that the European labels were much more cautious concerning the degree of pre-emphasis applied to 78 RPM records than were their American counterparts.

さて、記録可能時間を伸ばすために低域をカットするアイデアと、サーフェスノイズを軽減させるために高域を強調するアイデアは、(ある前提の下においては)本当に優れたアイデアであり、特にアメリカにおいては、1940年代に入ると徐々にレコードに適用されていった。実際、RIAA以前のアメリカ製レコードと、同時期のヨーロッパ製レコードの大きな違いは、市販の78回転レコードに対して高域プリエンファシスをどの程度かけるか、であった。ヨーロッパの方が高域プリエンファシス適用に非常に慎重であったと言って差し支えない。

This wasn’t simply fusty, European conservatism. America during this period wasn’t a colonial power as were many of the European nations (especially Britain and France). In wealthy, domestic America, electricity had reached most homes by the 1930s and electrical reproduction of sound was the norm. Not so for European manufacturers for whom a substantial market for records lay in the far-flung outposts of the empire where mechanical gramophones remained the predominant method of reproduction well into the fifties. The European record companies were only too aware that the more equalisation applied to records, the worse they sounded on a mechanical gramophone.

この違いは、ヨーロッパが保守的であったから、という単純な話ではない。この時代のアメリカは、ヨーロッパ諸国(特にイギリスやフランス)のように植民地支配をしていたわけではなかった。結果として裕福であったアメリカでは、1930年代にはほとんどの家庭に電気が行き渡っており、音楽再生も電気で行うのが当たり前になっていた。一方でヨーロッパのレコードレーベルにとって、実質的なレコード市場である遠方の植民地においては、1950年代に入っても依然としてアコースティック蓄音機による再生が主流であった。そしてヨーロッパのレコードレーベルは、イコライザ(高域プリエンファシス)をかければかけるほど、アコースティック蓄音機では音が悪くなることをよく認識していたのだ。

Historical Recording Characteristics: Technology and sociology (PSPATIAL AUDIO)今回の一連の記事においては、主に米国での事情を扱うため、イギリス/フランス/ドイツなどの事情については詳しく追わないのですが、このような事情から欧米間の差があった、ということは非常に勉強になりました。

As my whole series of articles primarily deal with the history of disc recording in the US, I will not deeply explore the history in UK, France, Germany etc. Anyway, I learned much from these paragraphs – such “History” made the difference of pre-emphasis application.

音楽だって、レコード録音再生技術だって、人類の歴史の一部分であり、音楽やオーディオに直接関係ない大きな流れの一部分でしかない、ということを再確認させられるエピソードです。

After all, music and disc recording/reproducing technology are tiny parts of the long history of Homo sapiens. I reaffirmed the fact that the big stream of time and general course of history just includes the history of music and disc recordings.

9.2.1 “Looking Ahead”, D.J. Julian, American Music Lover, July 1944

ちょうどこの時期、欧米間のプリエンファシスの違いについて触れている、かつ、第二次世界大戦中の米国における市販用レコード(78rpm)のイコライジングカーブに関連した、非常に興味深い記事が、American Music Lover という雑誌の1944年7月号に掲載されているのを見つけました。

Another article I could find also mentions the differences of pre-emphasis application between the US and Europe; and the article also discusses the situation of the varying equalizing curves applied to commercial 78rpm shellac records during the WWII. It appeared in July 1944 issue of American Music Lover magazine.

この雑誌は、1935年5月に刊行が始まったクラシック音楽のレコードコレクター向け月刊評論誌で、1944年暮れには American Record Guide と誌名を変更し、現在でも発行が続いています。1926年に発行が開始された元祖レコードコレクター向け雑誌 Phonograph Monthly Review と並び、当時のアメリカのレコードマニアの息吹を伝えてくれるものです。

The “American Music Lover” monthly magazine was first published in May 1935, then in late 1944 changed its name to American Record Guide – a famous review magazine for record collectors of Classical music, and it’s still being published now. It’s one of the precious resources that show us the lifes and atmosphere of Classical record collectors, along with another famous collector magazine Phonograph Monthly Review, first published in 1926.

残念ながら、American Music Lover July 1944 号は入手できておらず、現時点ではオンラインでも公開されていないのですが、Pt.0 の参考資料一覧 でも紹介した読み応え満点の本「From Tin Foil To Stereo: Evolution of the Phonograph」の中に当該記事が引用されているので、そちらを参照してみましょう。

Unfortunately, I have not yet obtained the July 1944 issue of American Music Lover magazine, and the particular issue is not available online. However, the article is quoted in the incredibly informative 1959 book “From Tin Foil To Stereo: Evolution of the Phonograph” that I mentioned at the “References” section of my part 0 article, so below are the quotations within quotations.

From Tin Foil To Stereo: Evolution of the Phonograph

Oliver Read & Walter L. Welch (1st edition 1959, 2nd edition 1976)

cover image from 45worlds, uploaded by LouisSidney.

なお、「From Tin Foil To Stereo」の当該箇所には、引用前にこんなことが書かれています。

「業界誌のテクニカルライターは、広告主との友好関係維持に関心があるため、装置や手法の欠陥をも弁護するコメントを載せていると容易に想像される。しかし、ごく稀に、真に率直な情報開示を行うライターもいる」。

それがこの D.J. Julian 氏の録音特性に関する記事というわけです。

Before the “From Tin Foil To Stereo” book quotes the article, it writes like this:

“As the technical writers of the trade papers are concerned with the maintenance of cordial relationships with the advertisers who support the publications of their writers, it is quite to be expected that rationalizations should be made about the deficiencies of methods and equipment. However, infrequently individual writers come forth with a truly candid disclosure”.

Such was this “Looking Ahead”, an article in regard to recording characteristics, written by D.J. Julian.

The utler absence of agreement as to recording characteristics before the war has been most disconcerting. It is noticeable that all the blatant, shrill experimentation by the engineers has been directed to the classical repertoire (surely, not the dance tune, which finds its way into the juke box, where experimentation would not be tolerated). How long suffering is the lover of good music!

(第二次世界大戦に入る前から今に至るまで)ディスク録音特性について全く合意がとられてこなかったことは、最も不愉快きわまりない。各社の録音エンジニアによる露骨でけたたましい実験が、全てクラシックのレパートリーにのみ向けられてきたことは注目に値する(もちろん、ダンスチューンのレコードは、実験が許されない現場であるジュークボックスで使用されるから、その対象外であった)。優れた音楽を愛する者がどれだけ長いあいだ苦しみを味わってきたことか!

“Looking Ahead”, D.J. Julian, American Music Lover, July 1944, quoted from “From Tin Foil To Stereo” (Read & Welch, 1959)冒頭からびっくりさせられます。すなわち、(忠実でフラットな再生のためではなく、ダイナミックレンジ拡大のために)ターンオーバー周波数を独自変更したり、独自のプリエンファシスを追加したりするのは、ジャズやポピュラーなどのジャンルで、というよりは、主にクラシック音楽のレコードの世界で行われていたらしいのです。もちろん、ジャズやポピュラーの世界でも、多少の記録特性の違いはあったのでしょうが、クラシックの世界ほど過激ではなかった、という辺りでしょう。

The opening sentence already surprise me: the author says, public experimentations on commercial records, of altering bass turnover frequency and application of independent treble pre-emphasis – for extending recorded dynamic range, not for faithful reproduction – were mainly conducted for classical 78rpm records. I guess such experimentation might be (or might not be) done for the Pops/Jazz releases to a certain degree, but not so extreme as in the classical releases.

私が戦前クラシックの78rpm盤を集めたりしていないので、この辺の事情は詳しくないのですが、明らかにクラシックの録音の方が、どのようにマイクを配置したか、どのようなセッティングでディスク録音をしたか、などのエンジニアノートが残っている可能性が高そうです。この辺りはまた改めて調査・勉強してみる機会を持ってみたいところです。

Since I am not an avid collector of pre-war classical 78rpm records, I am not familiar with the controversy of recording/reproducing curves for classical records in 1940s. But it is highly probable that, because the recordings of classical music involves much “serious” microphone placements and setting experimentation, a kind of detailed “engineering notes” might survive. I wish I have a chance to do research/study around here sometime.

そしてこの文章の “lover of good music” (優れた音楽を愛する者) という表現からは、クラシック音楽こそが芸術性に溢れた音楽であり、ダンス音楽(ジャズやポピュラーなど)は劣っている、と考えていたであろうことすら読み取れる気がします(深読みに過ぎるかもしれませんが)。

Also, by using the phrase “lover of good music”, the author might unconsciously revealed his thought that “classical music is the best in artistry – dance music (jazz, pop, etc) is inferior”, although I may be reading too much into it.

Since record publication from the early days of recording has been international in scope, technical advances should be more or less synchronized by important manufacturers throughout the world. It is a strange fact that, on the whole, Great Britain has lagged behind the rest of the field in putting into production some of the technical achievements consummated during the thirties. Why? Not because of the disinclination of the companies there to progress; for nowhere will be found such alertness and sensible cooperation by the industry with its customers. In England many of the most enthusiastic puchasers of records still cling to acoustic machines; and this bloc of the market must be reckoned with. The balance between bass and treble is unfavorable enough at best when a record is reproduced mechanically, without further robbing the low register to bloat the ‘highs.’

レコードのリリースは、初期の頃からある程度国際的なものであるが故に、録音技術の進歩は、世界中の主要メーカの間で多かれ少なかれシンクロしているはずのものである。しかし不思議なことに、大英帝国においては、1930年代に達成された技術的成果を未だに引きずり、遅れをとっている。それはなぜか? 実は英国の企業が進歩に対して消極的だからではなく、他の国では考えられないほど、産業界がコンシューマに対してこれほどまでに注意深く懸命な協力を行っているからだ。英国においては、レコードの熱心な購入者の多くが、いまだにアコースティック蓄音機に固執しており、このブロックのマーケットを無視するわけにいかない。レコードを機械的に(アコースティック蓄音機で)再生した場合、低域と高域のバランスがただでさえ悪いのに、さらに低音域を絞ったり(訳註: ターンオーバー周波数を更に上げて、の意)高域を肥大化させたり(訳註: 高域プリエンファシスを使う)することがあってはならないのだ。

“Looking Ahead”, D.J. Julian, American Music Lover, July 1944, quoted from “From Tin Foil To Stereo” (Read & Welch, 1959)この D.J. Julian 氏の論説においても、英国ではアコースティック蓄音機が依然根強い人気を得ていた(電気式増幅のオーディオがそんなに普及していなかった)ために、高域プリエンファシスの導入に慎重であったことについて触れられています。

The above part says the same story as PSPATIAL AUDIO web article – acoustic phonograph / gramophone machines were still popular in the UK (i.e. the diffusion of electrically amplified playback equipment was not yet), and the record manufacturers and engineers in the UK were discret enough to apply treble pre-emphasis.

そして Julian 氏は更に持論を続けます。

And Mr. Julian’s cherished opinion continues:

We should keep this point in mind; frequency range is not the most important single element in making records.

「(盤に記録可能な)周波数帯域(の広さ)が、レコード録音・製造において最も重要な要素というわけではない」。この点を我々は肝に銘じる必要がある。

“Looking Ahead”, D.J. Julian, American Music Lover, July 1944, quoted from “From Tin Foil To Stereo” (Read & Welch, 1959)この一文が、Julian 氏の最も伝えたかった点でしょうし、消費者(リスナー)の便を無視して、レーベル間/エンジニア間で技術競争を行うことは不毛だ、そう訴えたかったのだと思います。

This particular sentence may be what Mr. Julian wanted to stress the most – like “it is a barren attempt to strive for technology race among labels/engineers, ignoring the convenience of customers/listeners”.

さらに Julian 氏は続けて、ディスク録音・再生における規格が標準化されていないどころか、時代が進むほど各社の規格がバラバラになっている現状に対する批判を展開します。

Mr. Julian’s criticism continues – on the situation (at the time) of the lack of disc recording/reproducing standards, and the situation getting worse.

From the early experimental days of electrical recording until 1935, standards of groove shapes, depth of cut, and ‘Characteristics’ remained substantially stable all over the world. The system was called ‘constant velocity’; and in practice frequencies above 250 cps were engraved in a pure constant velocity characteristic (i.e., amplitude frequency equalled constant). Below 250 cps—called the ‘turnover’ or ‘crossover’ point—the cut was constant amplitude (all frequencies being limited to the same amplitude, instead of the amplitude increasing with a decrease in frequency).

実験的な最初期の電気録音から1935年あたりまでは、記録溝の形状や溝の深さ、そして「録音特性」の規格は、世界中で実質的に安定していたのである。この方式は「定速度」(constant velocity) と呼ばれる。実際には 250Hz 以上の周波数帯域において純粋な定速度特性(すなわち振幅周波数が一定)で刻まれていた。そして 250Hz、この周波数は「ターンオーバー」または「クロスオーバー」と呼ばれるが、それ以下の周波数帯域においては、等振幅特性(すなわち周波数の減少に伴って振幅が増加することなく、すべての周波数が同じ振幅に制限される)で記録されていた。

Beginning about 1935 the ‘crossover’ point was moved up to 500 or 600 cps in America, with the result that larger signals could be inscribed (so that the dynamic range was extended). This was all to the good. True, there was some loss in bass response, but reproducing instruments were corning off the lines with bass tone controls to compensate for this.

1935年頃から、米国においては「クロスオーバー」周波数が 500Hz ないし 600Hz に引き上げられた。その結果、より大音量の信号が盤に記録可能となった(すなわち、ダイナミックレンジが拡大された)。これは非常に良いことであった。確かに、低域のレスポンスは多少損なわれることになったが、再生機器側のトーンコントロールで低域を補正すればよかった。

“Looking Ahead”, D.J. Julian, American Music Lover, July 1944, quoted from “From Tin Foil To Stereo” (Read & Welch, 1959)この「1935年まではすべての国、すべてのレーベルで 250Hz がターンオーバー周波数だった」というくだりは、額面通りに受け入れる必要はありません。この記事が書かれた1944年(昭和19年!)当時の目線や知見から、D.J. Julian 氏が「電気録音黎明期」の話、すなわちベル研/WEのラバーラインレコーダによる録音について書かれている、と読むべきですが、専門家の研究により、現在では「米国では」「1930年〜1932年頃には」すでにターンオーバー周波数が500Hzに変更されたことが知られています。一方、英国や欧州では 300Hz 前後のターンオーバー周波数が大戦後にも使われていました。

The part “stable turnover frequency at around 250 cps until 1935” may not be taken too literally. The author D.J. Julian, from the point of view in 1944, might mention the frequency response of the early electrical recording system (Bell/WE “rubber-line” recorders). But by the extensive researches by professional researchers of recording history, the turnover frequency already moved up to 500Hz “at least in the US”. On the other hand in Europe, the turnover frequency around 300Hz had been used even after the WWII.

All too soon the recording characteristic fell into disrepute in this country: each engineer had his own ideas. Some wished to extend the ‘crossover’ point to 800 cps… to 1,000 cps… and perhaps even higher. What appeared to be a friendly rivalry sprang up among the brethren: to see who could make the loudest record.

ほどなく、この国において「録音特性」は評判を落とすこととなった。エンジニアはそれぞれに違うアイデアを持っていたのだ。クロスオーバー周波数を800Hzにあげようとするエンジニアもいれば、1,000Hzにまであげるエンジニアもいた。それ以上にあげたエンジニアもいたことだろう。誰が一番大きな音を記録できるか、エンジニア仲間の間で切磋琢磨しているかのようであった。

“Looking Ahead”, D.J. Julian, American Music Lover, July 1944, quoted from “From Tin Foil To Stereo” (Read & Welch, 1959)ここに書かれていることを鵜呑みにする必要はないかもしれませんし、私が米国のクラシック78rpm盤について無知なため正否を判断できないだけかもしれません。ともあれ、1944年において、D.J. Julian 氏(そもそもこの方は一体誰なんでしょう。。。どなたかご存知であれば教えてください)というレコード/オーディオ評論家が感じていた、レコード業界やホームオーディオ業界に対する不平不満を、臆せずぶちまけていることだけは伝わってきます。

You don’t have to believe everything he wrote without question. Or I just don’t have extensive knowledge on classical 78rpm records in the US and I have no idea to judge if these are correct. Anyway, D.J. Julian (does anybody know who he was? please let me know) – probably a music/audio critic – felt much dissatisfaction and discontent against record industry and home audio equipment industry at the time, and he might express his opinion in this article without hesitation.

そして、この Julian 氏の主張からは、これらの勝手きままな録音カーブの乱立は、広大なダイナミックレンジを必要とするクラシック音楽の録音だからこそ始まったものであり、ポピュラー音楽の録音の世界ではあまり起こっていなかったであろうことも、容易に推測されます。

And Mr. Julian’s assertion here naturally leads to a reasonable conjecture that, the state of being disorder – each engineering tried to extend crossover point of his/her own – primarily took place in the classical music field, that requires much wider dynamic range than popular music.

About this time, ‘phony high fidelity’ reared its monstrous head, when someone decided that increasing the intensity of frequencies in the 3,000 cps region would impart a spurious brilliance that sounded ‘nice’ on the cheap sets where the output transformers took anose dive on frequencies above that point. The effect was ear-splitting enough to cut through the noise of a boiler plate works, on a good machine, unless the treble tone control was jammed down hard to maximum attenuation.

ちょうどこの頃、邪悪な「インチキ・ハイファイ」が頭をもたげてきた。3,000Hz 近辺の周波数を少し持ち上げればそれっぽくブリリアントな音が出せる、と誰かが思いつき、高域ではトランスの出力が急降下する廉価なオーディオセットで「いい音」が出るようにしたのである。この効果は、優れた(高域まで十分に再生可能な)オーディオ機器においては、ボイラー圧縮機のノイズを切り裂くほど耳障りなものとなり、高域のトーンコントロールを最大限絞らないといけないほどであった。

There is a definite advantage to be gained if ‘peaking’ is skillfully executed, because the signal-to-noise ratio will be better. But to a specified ‘curve’ be reached by all companies; and then only if it appears that the advantage gained is sufficient to offset the obvious drawback; fussing with the tone controls every time we change from the London Philharmonic to the New York Philharmonic Symphony.

「ピーキング」(訳註: 正確には高域プリエンファシスではないものの、一部中高域を持ち上げることでプリエンファシスと同等の効果をもたらすもの)をうまく活用すれば、S/N比が向上するため、得られるメリットは大きなものとなる。しかし(「ピーキング」の活用は)すべての会社である特定の(統一)「カーブ」が採用されることが前提となるし、また、ロンドンフィルの盤からニューヨークフィルの盤に交換する度にトーンコントロールと格闘しなければならない、といった明らかな欠点が、(「ピーキング」の活用によって)得られる利点によって十分に相殺できる、と判断可能な場合に限られる。

“Looking Ahead”, D.J. Julian, American Music Lover, July 1944, quoted from “From Tin Foil To Stereo” (Read & Welch, 1959)Julian 氏の主張によると、当時はクラシック音楽のレコードですら、再生周波数帯域が十分ではない廉価な電蓄でよく聞こえるようにピーキングを行っていた、ということになります。

According to Mr. Julian’s assertion, even the classical records at the time, employed some kind of “peaking” to sound fine on the cheap sets.

繰り返しになりますが、この記事に書かれた個々の内容に正確性を求める必要はありません。しかし、カジュアルなリスナーではなく、真剣にレコードやオーディオに向き合っていた1944年当時のマニア・評論家の声として、この文章が伝えてくるニュアンスを受け止める必要があります。

Again, we don’t need to demand the precise correctness in every detail of his article. However, it surely is a real confess of a person from 1944 – a critic and a fanatic of records and audio equipment. So at least we better “read between the lines”, and appreciate the nuances to some degree.

プロフェッショナルな世界、すなわち放送局においては、縦振動トランスクリプション盤の録音・再生特性はずっと1種類で、横振動トランスクリプション盤の録音・再生特性も1942年にNABによって統一されました。しかし、コンシューマ向けの市販レコードについては、まったく統一がとれていなかったし、その具体的なパラメータも明らかになっていなかった(そして今に至るまで1940年代当時の確実な一次情報がほとんど見つからない)、またレコード製造側も再生機製造側も、統一しようという気すらなかった、そんな当時の状況がよく伝わってきます。

In the professional field – broadcasting industry – the recording/reproducing characteristic for vertical transcriptions had been only one type; that for lateral transcriptions was finally unified as 1942 NAB Standards. On the other hand, recording/reproducing characteristic for commercial (shellac) 78rpm records was “in complete confusion” – not unified at all. Not only such disunity was kept, but also the exact parameters of each recording characteristic was NOT made clear at the time – and even for now. Unlike the NAB Standardization, record manufacturers and audio equipment manufacturers at that time of the early-middle 1940s were unwilling to cooperate toward some sort of standardizations.

I question the wisdom of the thrusting upon the patient classical record buyer the capricious and whimsical babel of languages spoken by the companies’ engineers. Experimentation should be done in the laboratory —not on the public. A certain measure of sanity is desirable in recording. If frequency range alone is sought, this could be more effectively carried out with a 33-rpm motor and vertically recorded transcriptions.

忍耐強くクラシックレコードを購入する人々に、各レーベルのエンジニアが気まぐれで一貫性のない用語をまくしたて押し付けることに疑問を抱かざるを得ない。実験は実験室で行うべきで、一般大衆を対象にするべきではない。録音の世界では、ある種の「正気(しょうき)」が望まれる。もし周波数帯域(の拡大)のみを追求するのであれば、33 1/3回転のモーターと縦振動トランスクリプション盤を用意するだけで、効果的に遂行できるではないか。

When production of reproducing instruments is begun after the war, it is hoped that the amount of pickup equalization will be in harmony with what the engineers will put down in the wax.

戦争終結後、レコード再生機器の製造が再開する時に、録音エンジニアがワックス盤に刻む特性と、再生機側のイコライズ特性とが、手をとりあって調和していることが望まれる。

“Looking Ahead”, D.J. Julian, American Music Lover, July 1944, quoted from “From Tin Foil To Stereo” (Read & Welch, 1959)そして、この1944年時点においても、ベル研/WE の縦振動トランスクリプションとその技術に対する絶大な信頼を寄せている人が一定数いたことを示す文章と言えます。本稿 Pt.5 で紹介した、Fortune 誌1939年9月号の記事もそうでしたね。

Also, the above paragraphs are interesting because it shows immense trust in Bell/WE vertical transcriptions and its technology. Other example was the article “Phonograph Records” in Sep. 1939 issue of the Fortune magazine, as we already have seen on the part 5 of my article.

もちろん、市販のシェラック盤と比較して縦振動トランスクリプション盤に言及されているわけで、実際には当時ヴィニライト製の横振動トランスクリプション盤も存在していたわけですが、いずれにせよトランスクリプション盤は放送局向けであり、一般向けの市販は固く禁止されていました。それだけ「(現在の市販用シェラック盤より)高品質で録音再生できる技術がすでに存在しているのに、なぜそれを我々一般コンシューマに提供しないのか?」という気持ちの現れとも読めるでしょう。

Of course, the author is mentioning (vertical) transcription records to compare with inferior commercial shellac records, and there were vinylite lateral transcription records around. Anyway, transcription records were for broadcast stations and prohibited for commercial sale. So the author wanted to express like: “although the superior technology (to that of commercial shellac records) already exists, why won’t the manufacturers utilize such technology into the commercial market?”

文面から、クラシック音楽マニアかつレコードコレクターであったと思われる、この D.J. Julian 氏が、「どこまでダイナミックレンジを追求したレコードを作れるか」「どこまで周波数帯域を広げた録音ができるか」の競争に夢中になって、顧客をかえりみない、そんな当時の(主にクラシック音楽の)録音エンジニア達について、苛立ちを覚えているのが伝わってきます。実際のところ本当にそうだったのか、は、確認のしようがありませんが、当時のマニアや評論家からはそう見えていた、ということになります。

The article shows D.J. Julian’s aggravation against manufacturers’ stance of “friendly rivalry”, experimenting wider dynamic range and frequency range on records, taking no notice of what consumers feel. I am not sure if it really was such a situation at that time, but at least some consumers, enthusiasts and critics like D.J. Julian saw it as such.

そして、この記事を引用した書籍「From Tin Foil To Stereo」では、最後を次のように締めくくっています。

After this long quotation, the book “From Tin Foil To Stereo” concludes the section like below:

The advice of Mr. Julian to his fellow engineers was not followed. In fact the situation with respect to recorded characteristics became much worse than at the time he wrote his copy. The recorded characteristics of the current LP’s varied from company to company. There was even a difference in the diameter of the styli used to play them.

結局、技術者仲間に対する Julian 氏の忠告が守られることはなかった。むしろ、彼がこの記事を執筆した頃よりも、録音特性にまつわる状況は更に悪くなっていった。現在一般的であるLPが導入されてもなお、その記録特性は会社ごとレーベルごとにバラバラであった。再生用の針サイズが異なることすらあった。

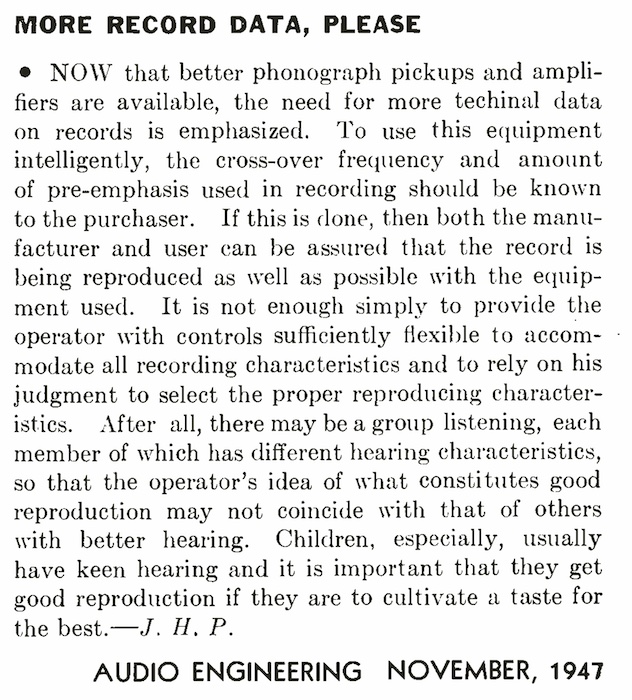

From Tin Foil To Stereo (Read & Welch, 1959)9.2.2 “MORE RECORD DATA, PLEASE”, Audio Engineering, November 1947

上で述べたような状況であったことは、戦後に発行された雑誌の編集ノートからも窺い知ることができます。

Another example showing similar controversy and recognition can be found in the “Editors’ Note” section of the post-WWII magazine.

1917年に創刊した雑誌 “Radio” を引き継ぐかたちで1947年に誌名を変更した、オーディオ技術雑誌 “Audio Engineering” は、翌年 AES (Audio Engineering Society) という学会を生み、1953年に学会誌 “The Journal of Audio Engineering Society” の刊行を開始したため、1954年によりコンシューマ向けの内容のみにシフトして、誌名もシンプルに “Audio” となります。ともあれ、その歴史ある Audio Engineering 誌の1947年11月号の Editor’s Report 欄に、編集者 John H. Potts 氏による “MORE RECORD DATA, PLEASE” という文が掲載されています。

“Audio Engineering” magazine, originally “Radio” magazine founded in 1917, and changed the name to “Audio Engineering” in 1947. It also hatched the AES (Audio Engineering Society) in 1948, and the first publication of “The Journal of Audio Engineering Society” was in 1953. This was why the “Audio Engineering” magazine renamed again in 1954, simply to “Audio”, and focused on consumer audio topics. Anyway, “Editor’s Report” section of the November 1947 issue of “Audio Engineering” has a short article entitled “MORE RECORD DATA, PLEASE”, written by the editor John H. Potts.

source: Audio Engineering, November 1947, Vol.31, No.10, p.2.

NOW that better phonograph pickups and amplifiers are available, the need for more technal data on records is emphasized. To use this equipment intelligently, the cross-over frequency and amount of pre-emphasis used in recording should be known to the purchaser. If this is done, then both the manufacturer and user can be assured that the record is being reproduced as well as possible with the equipment used.

蓄音機のピックアップやアンプの性能が向上した現在、レコードに関する技術的なデータの必要性が今まで以上に重要になってきている。性能が向上した機器を有効活用するには、ディスク録音において使われるクロスオーバー周波数とプリエンファシスの値が、レコードの購入者に伝えられる必要がある。そうすれば、機器製造者も、レコード再生を行うユーザも、そのレコードが可能な限り良好に再生できている、と確信できるようになるからだ。

It is not enough simply to provide the operator with controls sufficiently flexible to accommodate all recording characteristics and to rely on his judgment to select the proper reproducing characteristics.

ありとあらゆる録音特性に対応できるように、再生機器側に柔軟なコントロールを装備し、あとはリスナー自身に正しい再生カーブを判断させる、という単純な対応では十分とは言えないのだ。

After all, there may be a group listening, each member of which has different hearing characteristics, so that the operator’s idea of what constitutes good reproduction may not coincide with that of others with better hearing. Children, especially, usually have keen hearing and it is important that they get good reproduction if they are to cultivate a taste for the best.

というのも、人はそれぞれ聴力に差があるもので、集団でリスニングを行う場合、再生機器のオペレータが考える「良い再生」と、聴力に優れた人の考える「良い音」とが一致しない場合があるからだ。特に子どもは非常に鋭く優れた聴力を備えているものであり、良い音楽・良い音への感性を養うためには、良い再生音で聴かせることが重要である。

MORE RECORD DATA, PLEASE, John H. Potts, Audio Engineering, November 1947, Vol.31, No.10つまり、Potts 氏のこの文章は、「単に再生機器側でいかなるカーブにも対応可能にするだけでは不十分」、そして「レコード製造側が、どのような特性・カーブで記録したかをしっかり公にする必要がある」という主張です。同時にこれは、電気録音黎明期からLP登場後に至るまで、ずっと果たされなかった大問題でもあります。

So, Mr. Potts stresses in this article like: “it is not sufficient that reproducing equipments having a variable EQ setting feature”, and “record manufacturers should make public the detail of the recording characteristic (curve) used for every record”. Also at the same time, this huge problem has continued to exist since the early years – even after the advent of microgroove LP records.

そして、「市場に様々な記録特性が乱立する(しかも詳細が公開されていない)現状を改め、業界で標準規格を策定する」ことが、本質的な解決策になる、ということでもあります。

Also, it easily leads that the fundamental solution would be the standardization of recording/reproducing characteristic, correcting the situation of various characteristics being around (and technical details being kept confidential).

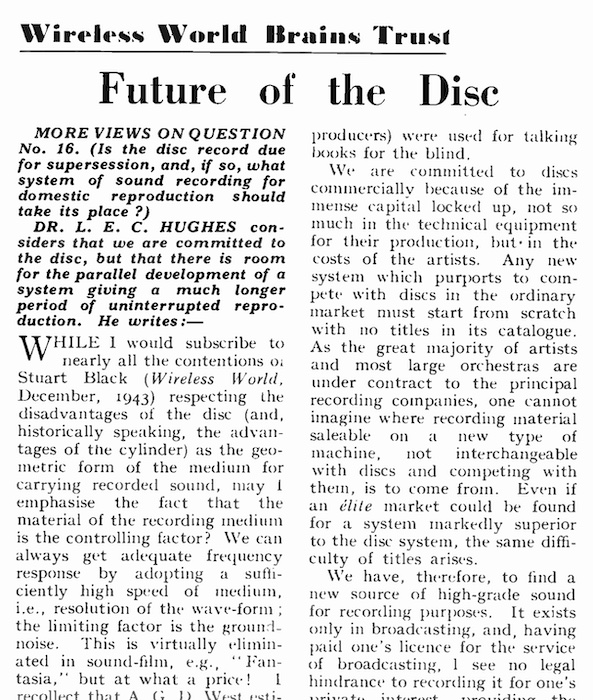

9.2.3 “Future of the Disc”, Wireless World (UK), January 1944

1940年代、すなわち大戦中かつLP登場前夜、の景色を映し出す秀逸な記事を、英国で発行された Wireless World 誌1944年1月号に見つけました。当時の市販レコードに対する不満とそれへの改善策提案といった内容です。

Another nice article I found is in the January 1944 issue of Wireless World UK magazine, displaying the situation of the 1940s (mid-war and post-war, pre-LP years). This article describes the discontent with the current (1940s) commercial shellac records, and some suggestions for improvements.

タイトルはストレートに「Future of the Disc」です。これは、1943年12月号 pp.378-379 に掲載された、Stuart Black 氏による辛辣な記事「Is Disc Recording Obsolete?」の続編で、L.E.C. Hughes 氏と Donald W. Aldous 氏がそれぞれ私見を述べているものです。

The article’s title is straightahead enough – “Future of the Disc”. This article was written by L.E.C. Hughes and Donald W. Aldous, and is a continuation of the sharp-tongued article entitled “Is Disc Recording Obsolete?”, that appeared in the previous issue (December 1943) of the Wireless World, pp.378-389.

source: “Future of the Disc”, L.E.C. Hughes & Donald W. Aldous, The Wireless World, Jan. 1944, Vol.50, No.1, pp.8-9.

Wireless World 誌 1944年1月号に掲載された “Future of the Disc” の冒頭部分

冒頭の Hughes 氏は、材質によるサーフェスノイズの問題をあげ、また内周に近づくほど線速度が落ちるため音質が劣化し、同時に(当時の重量級ピックアップでは)音溝がいとも簡単に摩耗し劣化してしまう問題を指摘しています。それらの問題を解決している技術は放送局業界にトランスクリプション盤として存在しているが、それらを使った新方式のディスクシステムを開発し市販したところで、タイトル不足の問題に直面する(主要なアーティストは大手レーベルと専属契約している)、と述べています。サーフェスノイズを撤廃でき、長時間再生できるようにするために、映画業界で使われているサウンド・オン・フィルム方式のフィルムが一般にも出回ることが望まれる、といったことも書いています。

Mr. Hugues shares his thought at the beginning: “may I emphasise the fact that the material of the recording medium is the controlling factor? We can always get adequate frequency response by adopting a sufficiently high speed of medium, i.e. resolution of the wave-form; the limiting factor is the ground-noise”, “The needle must wear, otherwise the material of the record would wear to a greater extent and reduce its own life. A distinct improvement would be to play the disc outwards instead of inwards”. He also express the cost of extending artists and repertoires if some new system was introduced: “As the great majority of artists and most large orchestras are under contract to the principal recording companies, one cannot imagine where recording material saleable on a new type of machine, not interchangable with discs and competing with them, is to come from”. And he express his desire to have filmic material like “sound-on-film” medium, “to take the longest uninterrupted musical or dramatic works” and “in such a way that the ground noise is at least as low in relation to the recorded sounds as the best records or modern sound-film”.

その他注目すべき意見としては、世界中のレコードレーベル間で、カッティング時の針のサイズすら統一されていない現状が、不必要な盤の摩耗を助長していること、カッティング時の溝間隔が国際的に統一されていないことの問題、などが記されています。

He points out the important thing as well: the standardisation of the exact dimensions of the cutting stylus among the recording companies throughout the world, saying “A bad fit of the reproducing needle in the groove leads, I am sure, to unnecessary wear of the record. If the two could be fitted together, and this could be done only by international agreement, I feel that records would not wear so quickly”. He also adds the lack of the international agreement on the spacing of grooves.

続く Aldous 氏は、British Sound Recording Association (英国録音協会) の技術部長で、1940年代当時の市販レコードの現状を鑑み、今後レコード録音・再生技術を向上させるための考察を試みています。以下引用します。

The latter half of this article was from Mr. Aldous, who was a Technical Secretary of the British Sound Recording Association. He tries to consider the technical issues of commercial records (in the 1940s), and any improvements for disc recording/reproducing, as quoted below:

The question “Is disc recording obsolete?” has long been debated among recordists and others interested in the subject. Briefly, the answer generally agreed upon at these discussions is “No: the disc recording system will continue to be of great use for domestic record reproduction purposes, but numerous improvments are urgently needed.” It is on the question of the desired improvements that no final agreement could be reached! (…)

「ディスク録音は時代遅れか?」という問いが、レコード会社やエンジニアなど関係者の間で長らく議論されてきた。この議論に対するほぼ同意のとれた回答は次のようになる。「否。ディスク録音はこれからも家庭用レコード再生目的に大いに役立つ。一方で、数多くの改善・改良が急務である」、と。しかしながら、ではどのように改善・改良すればよいか、その策については、最終的な合意には至れぬままである。(…)

Among the suggested improvements and modifications are the use of (a) the vertical or hill-and-dale cut, (b) constant amplitude recording, (c) constant groove-speed recording, (d) variable groove-pitch recording, (e) pressings in a “scratch-free” plastic, and such refinements as (f) standardisation of groove size, shape and pitch, (g) markings on record labels to show frequency characteristic used, and (h) the coefficient of compression, to permit the correct volume expansion coefficient to be used in reproduction, and, lately, (i) the use of an FM pick-up.

これまでになされてきた改善・改良の提案には、 (a) 縦振動記録、 (b) 定振幅記録、 (c) 線速度一定記録、 (d) 可変ピッチ記録、 (e) 「スクラッチフリーな」プラスチック盤へのプレス、などが含まれている。更には (f) 記録音溝のサイズや形状、ピッチの標準規格化、 (g) 使用された周波数特性のレコードレーベルへの記載、 (h) 正しい体積膨張係数を再生時に使用できるような圧縮係数、などの改良提案もあり、最近では (i) FM (周波数変調) ピックアップの使用、なども提案されている。

Future of the Disc, Donald W. Aldous, Wireless World, January 1944, p.9その他、家庭用サウンド・オン・フィルムの普及のために必要な技術改善案などについて述べていますが、割愛します。

He also describes his thought on the status and possible improvments for film recordings for home use, but it is omitted in this article of mine.

この雑誌は英国発行のもので、米国における事情とは異なる側面もあるかもしれません。しかし、米国における先進的な取り組みや研究結果は大西洋を超えて英国でも受け止められ、当時の市販レコードをどうやって改良すべきか、についての議論が広く行われていたことが伝わる連続記事となっています。

“Wireless World” magazine was an UK publication, and it might contain different opinions or perspective from those in the US. Anyway, this article (and the preceding article in Dec. 1943 issue) shows that the most advanced researches, developments and experimentations (at that time) in the US were surely across the atlantic, and were propagated in the UK as well.

9.2.4 “Report of Technical Session at Gramophone Conference”, 1939

少し時代はさかのぼりますが、上述の Wireless World UK 誌と同様の議論が、American Music Lover 誌1939年4月号 に掲載されていたので紹介します。これは、1938年11月4日〜7日に英国ホッデスドンで開催された Gramophone Conference (蓄音機会議) におけるテクニカルセッションを伝えた記事です。テクニカルセッション全体のタイトルは「Modern Developments in Sound Reproduction」(音響再生における最新の開発について) と銘打たれました。この記事を書いたのは、上の Wireless World 誌の記事にも登場した、英国録音協会技術部長の Aldous 氏です。

Now going back to 1939, to see the similar topic as the above “Future of the Disc” article in the Wireless World magazine. Below is an interesting article, published in April 1939 issue of American Music Lover, reporting the technical session at the Gramophone Conference, held at High Leigh, Hoddesdon, during the weekend of November 4-7, 1938. The general title of the technical session was “Modern Developments in Sound Reproduction”. The author of this article is Donald. W. Aldous, who also appeared in the 1944 “Future of the Disc” article on Wireless World UK.

同テクニカルセッションで行われた4つの発表はどれも興味深いもので、Decca のシニアエンジニア A.C. Haddy 氏による「Modern Disc Recording Equipment」(最新ディスク録音機器について)、EMI の技術録音マネージャ W.S. Purser 氏による録音セッションにおけるエンジニアについての発表、本稿 Pt.4 や Pt.5 でも登場した Harvey Fletcher 氏によるサウンド・オン・フィルム方式の録音に関する発表(Fletcher 氏不参加のため H.T. Greenfield 氏が代理発表)、そして Aldous 氏によるアセテート録音機に関する発表でした。

Four talks at the technical session were all interesting enough – “Modern Disc Recording Equipment” by A.C. Haddy, Senior Engineer at Decca Record Company Ltd.; discussion by W.S. Purser, Tehnical Recording Manager for EMI, on the intensive work by many engineers necessary to produce any marked improvement in recording quality; a paper by Harvey Fletcher (who already appeared in my part 4 and part 5 of my article) on the elements of sound-on-film recording (H.T. Greenfield read on behalf of Mr. Fletcher in his unavoidable absence); and finally the talk by Mr. Aldous himself on sound recording by amateurs, namely with instantaneous disc recorders.

発表終了後、参加者らによって活発なディスカッションが行われたそうで、以下はその描写です。

After the presentations, debate was conducted by the participants at the technical session. Following quote captures the atmosphere.

In the subsequent debate, which terminated the proceedings, the following were the major topics discussed –

セッションの締めくくりとして、続いてディベートが行われ、以下のような主要トピックについて議論が行われた。

(a) the need for long-playing records, which could be obtained by using the “constant linear speed” system or the “variable-pitch” method in which the number of grooves per inch is made capable of continuous adjustment to conform to the sound level at any moment during the actual recording;

(a) 長時間再生レコードの必要性。これは「線速度一定」システムの導入、または録音時に音量に応じて記録ピッチを柔軟に変化可能な「可変ピッチ」方式によって実現可能と考えられる。

(b) reduction of surface-noise by employing the “constant amplitude” system in which sounds of the same energy have the same amplitude, irrespective of frequency — a specially designed pick-up together with tone-correction in reproduction would automatically increase the “music-to-noise” ratio;

(b) 周波数にかかわらず同じエネルギーは同じ溝振幅で記録する「定振幅方式」システムによるサーフェスノイズ低減。専用設計されたピックアップと再生時のトーンコントロール活用により、「音楽対ノイズ」比(music-to-noise ratio)を向上させられる。

and finally (c) the value of “contrast or volume expansion” when reproducing certain orchestral records.

そして最後に (c) ある種のオーケストラ演奏のレコードを再生する際の「コントラストや音量の拡大」の価値について。

Report of Technical Session at Gramophone Conference, Donald W. Aldous, American Music Lover, April 1939, Vol.IV, No.12, pp.431-4321938年時点ですでに「定振幅記録」や「線速度一定記録再生」の話が出てきていることに驚かされましたが、いずれにせよ両者とも実用化されることがなかったことは時代が証明しています。唯一実用化されたのは「可変ピッチ」だけでした。

I am surprised to see the topics like “constant amplitude recording” and “constant linear speed recording/reproduction” in the context of 1938 Conference. After all, both methods never became in practical use. The only exception is “variable-pitch” method.

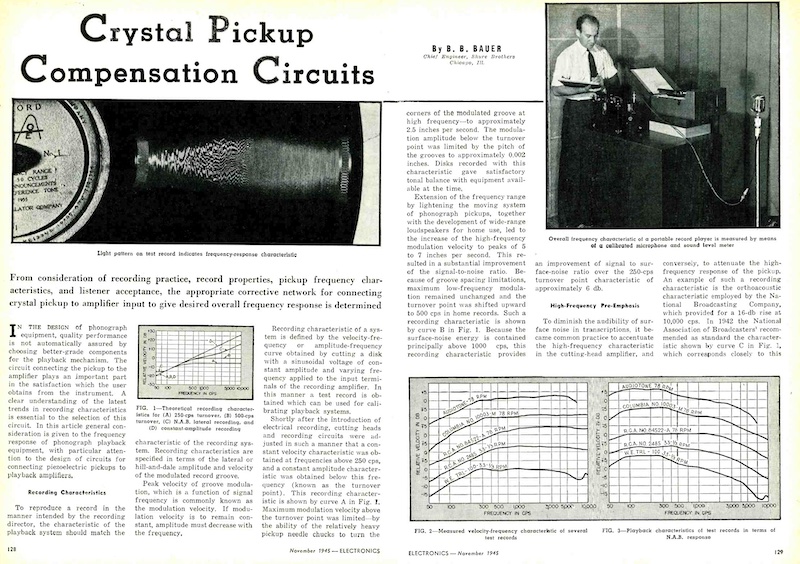

9.2.5 “Crystal Pickup Compensation Circuits”, Electronics, November 1945,

Electronics 誌の、戦後直後に刊行された1945年11月号にも、録音・再生特性に関する興味深い記述を認めることができます。

The November 1945 issue (thus a few months after the end of the WWII) of Electronics magazine also carries yet another interesting article regarding recording/reproducing characteristics.

タイトルは「Crystal-Pickup Compensation Circuits」(圧電ピックアップ用補正回路)で、ちょうど 本稿 Pt.7 で扱った、クリスタルカートリッジに関連する記事なのですが、この中に当時の市販用シェラック盤についての記載があります。

As the title “Crystal-Pickup Compensation Circuits” says, it deals with crystal pickups and accompanying compensation circuits, as we have seen in the part 7 of my article. But it also describes the general features of commercial shellac records.

著者は B.B. Bauer 氏で、あの有名なマイクロフォン / フォノカートリッジメーカである Shure のチーフエンジニアです。当時 Shure は圧電(クリスタル)カートリッジを製造販売していたので、その文脈で書かれた記事ということになります。

The author B.B. Bauer was a chief engineer at Shure Brothers, a famous microphone / phono pickup manufacturer, needless to say. Shure Brothers at the time manufactured and sold piezo-electric (crystal) phono pickups, and it was why Mr. Bauer authored this article under the title mentioned above.

source: “Crystal Pickup Compensation Circuits”, B.B. Bauer, Electronics, November 1945, pp.128-132.

圧電カートリッジで再生EQをどのように実現したらいいか、の記事

当記事は主に、全周波数帯域で等振幅特性を持つクリスタルカートリッジで、市販のレコードやトランスクリプション盤を忠実再生するために、どのような補正回路を用意すべきか、回路図も添えて具体的に論じていますが、そこでは当時の各レーベルが出していた周波数テストレコードの特性についても触れられています。

This article primarily deals with the compensation circuits (with their schematic circuit diagrams) for crystal pickups, when reproducing commercial 78rpm records and electrical transcription records. It also mentions the “frequency test records” released by various labels at the time.

ここで一点注意すべきことは、LP時代に入るとさまざまなテストレコードが市販されますが、LP以前における当時のテストレコードというのは、市販を目的としたものではなく、各ラジオ放送局が機器の特性を計測・微調整するため、さらには電蓄(レコードプレーヤ)製造メーカが再生EQ回路設計の参考にするため、などに使われた、業務用の特殊なレコードであったということです。

Please note that these “frequency test records” from the pre-war era, unlike various “test records” in the LP era, were NOT intended for commercial market. They were manufactured for use of strict measurements, calibration and fine-tuning of the equipments at radio stations; or for use when developing reproducing equalizers of the electrical phonograph players. It was such a special test record for business/professional use.

Test records provide convenient and precise means for testing and adjusting the response of playback systems. The test record need not be recorded with the exact characteristic which is desired for the playback system, as long as its characteristic is known. Most test records are recorded with a constant amplitude characteristic up to the turnover point, and a constant velocity characteristic above the turnover point.

テストレコードは、再生システムの応答特性をテストし調整するための、便利で正確な手段を提供する。このようなテストレコードは、どのような特性で記録されているかだけ分かればよく、実際の(市販される盤に記録された、つまり再生機側の補正回路とピッタリ一致した)正確な特性で記録されている必要はない。多くのテストレコードでは、ターンオーバー周波数以下は定振幅特性で、ターンオーバー周波数以上は定速度特性で記録されている。

Among American-made lateral test records are Audiotone No.78-1 (250 cps turnover), Columbia Frequency Record No.10003-M (300 cps turnover), and R.C.A. Frequency Record No.84522 (500 cps turnover). These are 78-rpm records intended for use with home record players.

そのような米国製の横振動テストレコードには、Audiotone 社の No.78-1(ターンオーバー 250Hz)、Columbia 社の周波数レコード No.10003-M(ターンオーバー 300Hz)、そして RCA 社の No.84522(ターンオーバー 500Hz)などがある。これらは全て78回転盤であり、家庭用レコードプレーヤを念頭においたものである。

“Characteristics of Shellac Pressings”, Crystal Pickup Compensation Circuits, B.B. Bauer, Electronics, Nov. 1945同時に当記事では、当時流通していた市販用レコードの特性について、更には一般論としてレコード再生における補正についても論じています。

This article also describes the characteristics of commercial shellac records, as well as playback compensation in general.

Characteristics of Shellac Pressings

シェラック盤の特性

The manufacturer of home records is confronted with a number of factors which have a bearing upon response-frequency characteristics. Home records are employed in an extremely wide variety of record players with different characteristics, in coin-operated machines, and in broadcast work. Such factors as needle tracking, recorded level, and surface noise, all of which are interdependent with response characteristics, are given different weight by various manufacturers and users. One finds, as a result, a difference between response-frequency characteristics of records manufactured under various brand names.

市販の家庭向けレコードのメーカは、周波数応答特性に関係する多くの要因と直面している。家庭向けレコードは、それぞれ異なる特性を持った多種多様なレコードプレーヤで再生されるほか、ジュークボックスでも再生され、また放送局でも再生される。針先による溝のトレース性能、録音レベル、サーフェスノイズなど、周波数応答特性に相互に依存しあう要因については、メーカやユーザによってその比重が異なっている。結果として、製造レーベルごとに周波数応答特性が異なることに気づくこととなる。

Because of these differences in recording characteristics, a single playback response cannot meet all requirements and a compromise must be sought. It is to be expected that standardization work may be done in the future to remedy this situation.

これら録音特性の違いにより、単一再生特性で全ての要求を満たすことはできず、妥協点を探さなければならない。この状況を改善するために、標準化作業が将来行われることが期待される。

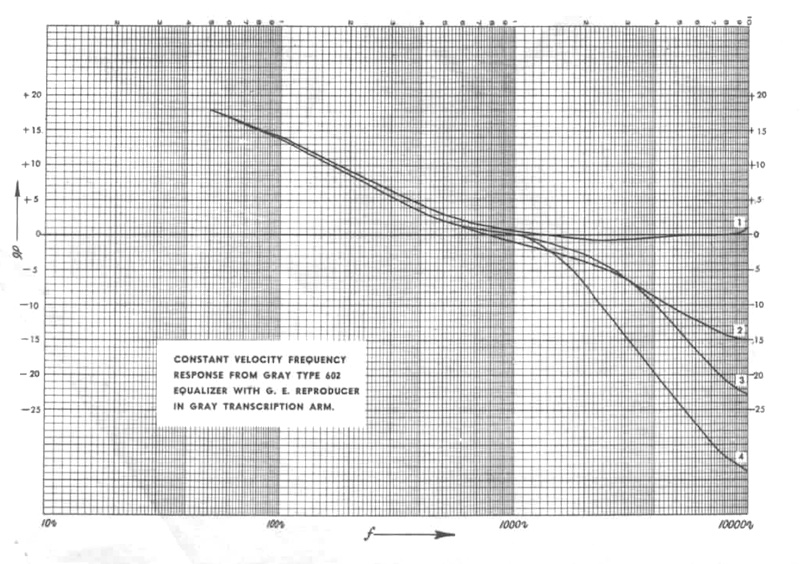

Most recent recordings exhibit a good tonal balance when played back with a pickup adjusted to conform to the N.A.B. Standard. Other records provide a better balance when reproduced with a pickup which is flat on a velocity basis beyond the 500-cycle turnover point. However, surface-noise considerations in shellac-type home records dictate a reduction of high-frequency response of the playback roughly in accordance with the N.A.B. Standards. For reasons which are stated later, attenuation greater than prescribed by N.A.B. Standards is often desirable beyond 4,000 to 5,000 cps. There is little doubt that useful frequency content in commercial records beyond 8,000 cps is negligible.

近年のレコードは、NAB規格に準拠したピックアップで再生すると、音色バランスが良くなるものが多い。一方で、ターンオーバー周波数である500Hz以上をフラット再生する(訳註: 500Hz 以下が等振幅、500Hz が定速度)方が良いバランスになるレコードもある。ただし、シェラック製である家庭向けレコードにおいては、サーフェスノイズを考慮し、NAB 規格におおよそ準拠したかたちで高域を減衰させることとなる。後述する理由により、4,000〜5,000Hz を超える領域については NAB 規格かそれ以上の減衰が望ましい。また、市販のレコードにおいては、8,000Hz を超える高域においては、再生に有効な周波数成分がほとんど含まれていない点は疑う必要がないだろう。

“Characteristics of Shellac Pressings”, Crystal Pickup Compensation Circuits, B.B. Bauer, Electronics, Nov. 1945ここでも、マイクログルーヴ LP 登場前におけるディスク録音再生における特徴が繰り返されています。ヴァイナル製であった放送局用のトランスクリプション盤と違い、市販レコードはシェラック製で、サーフェスノイズの問題が高品質再生における最大の問題であったこと。そのサーフェスノイズの問題の大きさに比べれば、「正確なイコライジングカーブ」はそれほど深刻とは受け止められていなかったこと。そしてそのカーブの違いもかなりざっくりと扱われていたこと、などです。

Again, this article also mentions infamous topics on disc reproduction – surface noise, and it describes that the attenuation of high-frequency response may contribute better fidelity playback. As we see, in the 1940s, “Truly-uniform playback EQ curve” was far less important than “reducing surface noise for comfortable listening experience”; differences among various “recording curves” were treated so roughly as the two groups of “flat above 500Hz” and “NAB Standards”.

しかも、この記事が掲載されたのが、歴史ある技術系業界雑誌である Electronics 誌であることは重要です。かつ、当該記事の執筆者が、一般リスナーでもなく、オーディオ評論家でもなく、Shure Brothers のチーフエンジニアであることも見逃せません。当該記事末尾には、記事を書くにあたって当時の業界の錚々たるメンバに協力を仰いだ、という謝辞すら掲載されており、記事内容の中立性・(当時としての)正確性は十分に担保されているといえるでしょう。

I think I need to stress that this article was published in the “Electronics” magazine, a famous/technological trade journal which began in 1930; that the author was the chief engineer of the Shure Brothers – not an amateur listener nor an audio critic. Furthermore, the final section of this article delivers acknowledgments of the help by state-of-the-art engineers at the time. So we can say this article has a certain degree of neutrality and correctness (at the time).

The author is grateful to the following persons for helpful discussion and for information regarding response characteristics: J. Dickert of Decca Records, Inc.; W.R. Dresser of the Audio-Tone Oscillator Company; H.S. Knowles of the Jensen Radio Corp.; V.J. Liebler of Columbia Recording Corporation; R.A. Miller of Bell Telephone Laboratories; A.A. Pulley and H.I. Reiskind of the Radio Corporation of America.

(本記事執筆にあたり)筆者は、以下の個々人と有意義な議論を行えたこと、また応答特性に関する情報提供をしていただいたことに、深く感謝するものである。デッカレコード社の J. Dickert 氏; オーディオトーンオシレータ社の W.R. Dresser 氏; ジェンセンラジオ社の H.S. Knowles 氏; コロンビアレコーディング社の V.J. Liebler 氏; ベル研の R.A. Miller 氏; そして RCA 社の A.A. Pulley (Albert Pulley) 氏と H.I. Reiskind 氏である。

“Characteristics of Shellac Pressings”, Crystal Pickup Compensation Circuits, B.B. Bauer, Electronics, Nov. 1945さらに記事は進み、高域補正についての議論が行われます。ここでは、シェラック盤の宿命であるサーフェスノイズを軽減するために、スクラッチフィルタとしての高域減衰(ローパスフィルタの適用)の必要性が語られています。さきほど引用した通り、当時の市販78rpm盤には、8,000Hz 以上には有効な音信号がほとんど含まれていなかったため、人間の耳が特に敏感なそういった高域をフィルタすることで、心地よい再生音を提供する、という理屈です。

The article continues to the discussion of high-frequency compensation. The author describes the need of low-pass filter (high frequency attenuation) for reducing surface noise that cannot be essentially avoided from shellac record playback. The author wrote above as “useful frequency content in commercial records beyond 8,000 cps is negligible”, so he claims that the attenuation of high-frequencies (where the ears are very sensitive) may contribute better “comfortable” playback.

High-Frequency Compensation

高域の補正

Because the recording characteristic varies from one record to another, it is not feasible to specify with precision what response is apt to produce the most faithful reproduction. As has been pointed out, records appear to produce best fidelity when the response above 1,000 cps is flat on a constant velocity basis. Some of the newer recordings provide excellent results when played with a pickup adjusted in accordance with the N.A.B. Standards. For maximum flexibility, it appears best to have a pickup with an inherent high-frequency response somewhat higher than that required by the N.A.B. Standards. This response can be lowed, if necessary, by means of a conventional tone control circuit incorporated in later stages of the amplifier.

録音特性はレコードごとに異なるため、どのような応答(再生補正)が最も忠実に再生できるものか、を正確に特定するのは不可能である。すでに指摘されている通り、1,000Hz 以上のレスポンスを定速度フラットに再生すると(訳註: いま風にいうと「ロールオフ FLATにすると」)、レコードを最も忠実に再生できるようである。新しいレコードの中には、NAB規格に準拠したピックアップで再生すると、素晴らしい結果が得られるものもある。よって、最大限の柔軟性を備えるには、NAB標準規格が要求するより高い周波数を再生可能なピックアップを用意することが最善と思われる。そしてこの高域レスポンスは、アンプの後段に組み込まれた従来のトーンコントロールにより、必要に応じて下げることが可能である。

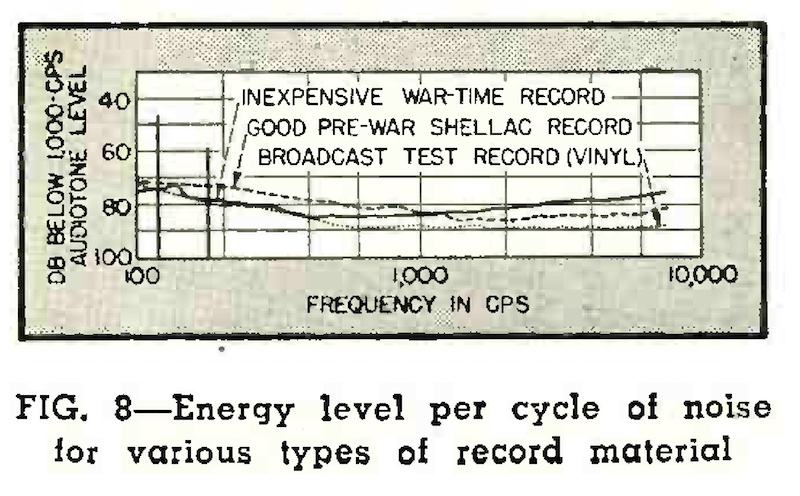

The high-frequency range most acceptable to the listener is determined, to a large extent, by surface noise. The surface noise energy content for various recording materials is shown in Fig.8. Surface noise energy is distributed over practically all of the audible range on the basis of approximately equal energy content per cycle. Therefore, the effects of surface noise can be eliminated most easily by removing the higher end of the frequency spectrum, which contains the most surface noise energy per octave in the range where the ear is most sensitive to low level sounds.

リスナーに最も受け入れられやすい高周波領域は、サーフェスノイズによって大きく左右される。様々なレコード材質によるサーフェスノイズのエネルギー量を図8に示す。サーフェスノイズのエネルギーは全周波数帯域においてほぼ均等に分布している。したがって、サーフェスノイズのエネルギーが1オクターブあたり最も多く含み、かつ低レベルの音に対して耳が最も敏感な領域である、周波数スペクトラムの高域部分を除去することにより、サーフェスノイズの影響を最も容易に回避することが可能である。

“Characteristics of Shellac Pressings”, Crystal Pickup Compensation Circuits, B.B. Bauer, Electronics, Nov. 1945

source: “Crystal Pickup Compensation Circuits”, B.B. Bauer, Electronics, November 1945, pp.128-132.

良質な戦前シェラック盤、廉価な戦時中シェラック盤、放送局用ヴァイナル製テストレコード、のサーフェスノイズのエネルギー分布グラフ

そして本記事は高域歪に関する論考へと続き、最後は「実際にリスナーにシェラック盤を試聴してもらい、どの程度高域カットオフするのが好ましいと回答したか」のテストの話へと続きます。やはり当時の市販用レコード再生では、高域をローパスフィルタでカットすることで再生品質を確保しようとしていたことが伺えます。

Finally this article enters the topic of playback distortion especially in the high frequency range; he describes a brief summary of the tests he conducted, of “reproduction of home (shellac) records in front of listeners, and meature their preference to high-frequency cut-off”. This test also reveals the trend (at the time) of high-frequency attenuation for better playback experience.

Listener Tests

リスナーテスト

Distortion is another factor which has an important bearing upon the optimum high-frequency cut-off of the pickup. The origin of this distortion is (a) the relatively large radius of needle tip required to track properly in conventional record groove, (b) distortion inherent in the process of duplicating commercial records, and (c) distortion which takes place in playback equipment. Distortion due to these causes can attain values as high as 15 to 20 percent on a direct measurement basis (not including intermodulation effects). Removal of response at high frequency is instrumental in reducing the annoyance caused by this type of distortion.

(サーフェスノイズに加えて)歪もまた、ピックアップの高域カットオフに重要な影響を与える要因である。この歪の原因は、 (a) 一般的なレコードの溝を正しくトラッキングするために必要な針先半径が比較的大きいこと、 (b) 市販レコードの複製過程で生じる歪み、 (c) 再生装置で生じる歪、などがある。これらが原因で発生する歪は、直接測定で 15%〜20% にも達する(相互変調の影響は含まない)。再生時に高域レスポンスを除去することで、このような歪による不快感の軽減が行える。

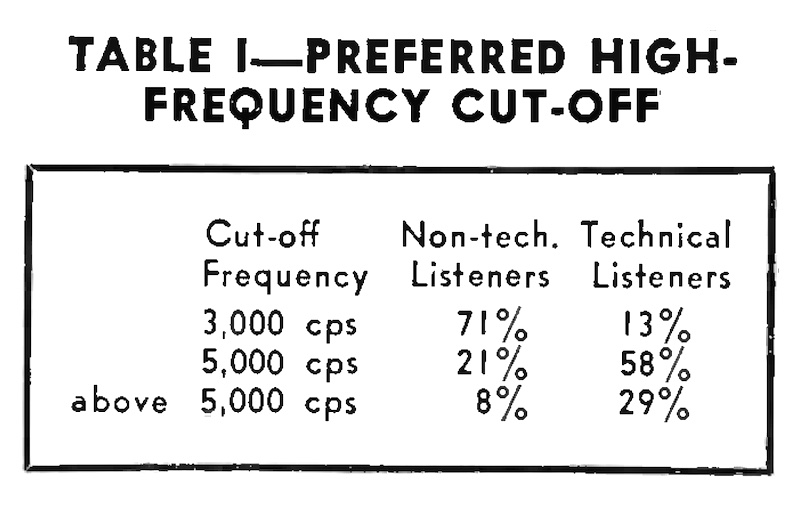

The author has conducted a number of tests to determine the preference of listeners to high-frequency cut-off in the reproduction of home records. The tests were given to 100 non-technical listeners, and to over 100 radio engineers (6). While a description of these tests is outside the scope of this article, the results given in Table I, although not conclusive, indicate that in the reproduction of home records, response above 5 kc exaggerages the effects of surface noise and distortion out of proportion to the improvement in fidelity. High-frequency cut-off can be obtained through the use of specially designed needles, or it can be obtained electrically with conventional low-pass filters.

筆者は、家庭用レコードの再生において、高域カットオフに対するリスナーの好みを調査するため、テストを実施したことがある。このテストは、技術者ではないリスナー100名、およびラジオ技術者100名以上を対象に行われた (脚注6)。このテストに関する詳細な説明は本記事の範囲外であるが、表Iに示した結果は、決定的なものではないにせよ、5kHz 以上の応答は、忠実に再生しようとすればするほど、サーフェスノイズや歪の影響を大きく出してしまうことを示している。この高域カットオフは、特殊形状の針を使って実現できるし、また従来のローパスフィルタで電気的に実現も可能である。

source: “Crystal Pickup Compensation Circuits”, B.B. Bauer, Electronics, November 1945, pp.128-132.

一般リスナーの71%が、3,000Hz での高域カットオフを好み、ラジオ技術者の87%が、5,000Hz 以上での高域カットオフを好む、と回答している

This situation is, of course, totally different in the reproduction of broadcast-type transcriptions produced on low surface noise material and carefully processed to keep the sources of distortion to a minimum.

もちろん、サーフェスノイズの少ない素材で製造され、歪の原因を最小限に抑えるよう注意深く処理されている、放送用トランスクリプション盤の再生においては、この状況は全く異なる。

(6) Method of administering preference tests and the results obtained were described in a paper presented by the author before the Acoustical Society of America on May 12, 1945.

(脚注6) 嗜好性テストの実施方法、およびテストにより得られた結果は、1945年5月12日にアメリカ音響学会で発表された論文に記載されている。

“Characteristics of Shellac Pressings”, Crystal Pickup Compensation Circuits, B.B. Bauer, Electronics, Nov. 19459.2.6 “Practical Disc Recording”, 1948

まだまだ紹介したい資料がたくさんあるのですが、最後に、録音サイドから書かれた書籍をみてみましょう。

One last example (although I have many more articles and books I want to introduce) is a book from the recording’s point of view.

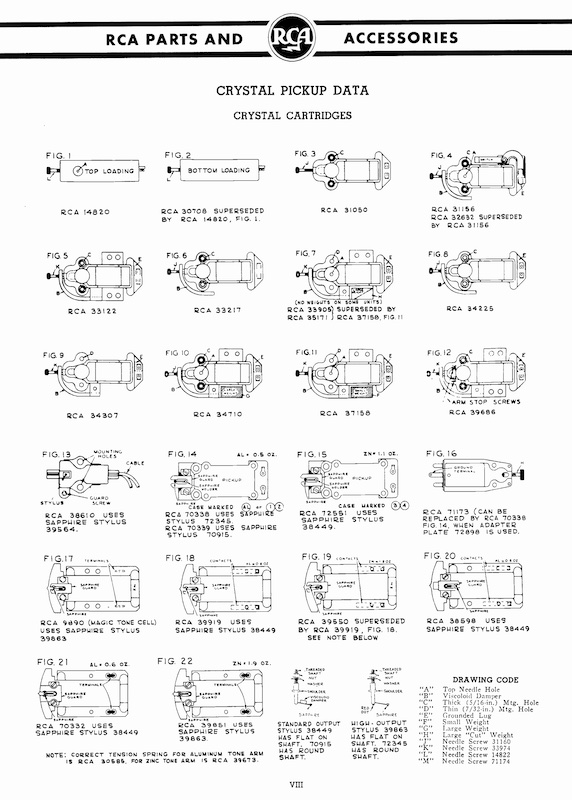

1948年(すなわち、ぎりぎりマイクログルーヴLP時代直前)に刊行された、“Practical Disc Recording” という書籍があります。これは、H.G. ウェルズや ジュール・ヴェルヌと並び「SFの父」の1人としても有名な ヒューゴー・ガーンズバック (Hugo Gernsback) 氏が監修した技術書籍シリーズの中の1冊で、Richard H. Dorf 氏が執筆した、アマチュアおよびセミプロ向けのディスク録音解説書です。

The book, entitled “Practical Disc Recording”, published in 1948 (so just before the advent of microgroove LP records), was one volume of the series of technical books aimed for amatenur / semi-professional readers, authored by Richard H. Dorf, supervised by Hugo Gernsback who is sometimes called “The Father of Science Fiction” along with H.G. Wells and Jules Verne.

“Practical Disc Recording”, Richard H. Dorf, Gernsback Libary No.39, 1938

The purpose of this book is to introduce the radio enthusiast to the art of disc recording and to explain in practical terms the elements of making high-quality records. Disc recording requires no more mechanical ability or knowledge than the average radioman possesses. It can be a fascinating and productive adjunct to radio, or a business or hobby in itself. Many hours of pleasure and profit can be spent in designing and constructing recording systems.

本書の目的は、ラジオ愛好家にディスク録音の技術を紹介し、高品質のレコードを作るための要素を実践的に説明することである。ディスク録音は、平均的なラジオ業界の人々が持っている以上に機械的技術や知識を必要とはしない。本書は、ラジオを楽しむための魅力的で生産的な補助ツールとして、あるいはビジネスや趣味として活用できる。録音システムの設計と構築を通じて、多くの楽しみと利益を得ることができる。

Preface, “Practical Disc Recording”, by Richard H. Dorf, Gernsback Library No.39, 1948この96ページのコンパクトな書籍自体が、1948年当時のディスク録音再生技術およびその基礎理論を概観する、非常に優れた内容となっているのですが、その中で注目すべきなのは、11章「イコライゼーション」において、当時の市販レコード(78rpm)の高域プリエンファシスについて触れている箇所です。

This 96-page compact book itself is worth reading – showcasing the excellent summary of the basic of disc recording/reproduction and its related basic theories, and in the Chapter 11 “Equalization”, there is concise description of “High-Frequency Pre-Emphasis”.

High-Frequency Pre-Emphasis

高域プリエンファシス

After a good standard modified-constant-velocity response has been obtained, some thought can be given to special curves. Commercial phonograph records are made of a shellac compound, an abrasive included in it causing surface noise or scratch. Many phonograph users turn down the tone control to eliminate this, but, in so doing, they eliminate much of the high -frequency range of the record as well. For this reason, record manufacturers boost the high end of the range in recording. When this is done, using a tone control to reduce high-frequency surface noise brings down the boosted highs to the proper value.

標準的な「修正版定速度特性」(訳註: ターンオーバー周波数以下が定振幅特性で、それ以上が定速度特性)が得られたら、特殊なカーブについて考えることができる。市販の蓄音機用レコードはシェラック化合物で作られており、その中に含まれる研磨剤がサーフェズノイズやスクラッチノイズの原因となっている。これを除去するために、多くの蓄音機ユーザはトーンコントロールを使って高域を減衰するが、これによってレコードに記録されている高域成分もかなり減衰してしまう。そのため、レコードメーカは高音域を強調して記録している。この場合、トーンコントロールで高域のサーフェスノイズを減衰すれば、ブーストして記録された高域が適切に再生されることになる。

While this is not necessary with instantaneous discs because of their very low noise level, the recordist may want to try high boost on the premise that many cheap phonographs lack good high-frequency response.

即時再生用のアセテート録音機の場合は、ノイズが非常に少ないのでその必要はないが、安価な蓄音機の多くは高域のレスポンスがあまり良くないということもあり、高域ブーストの録音を試してみるのも良いだろう。

Experimentation is fairly simple, if the equalizer in the amplifier is sufficiently versatile. One record manufacturer, for instance, raises the high frequencies at the rate of 2 1/2 db per octave, beginning at turnover. This results in a 10-db boost at 8,000 cycles after which he cuts off the response very sharply. Many phonographs are excessively boomy, so experiments with a bass attenuator may he fruitful.

アンプのイコライザが十分に多機能であれば、実験は非常に簡単となる。例えば、あるレコードメーカでは、ターンオーバ周波数から1オクターブあたり2.5dBの割合で高域増幅を行っている。その結果、8,000Hz で 10dB のブーストとなり、それより上の周波数は急速に減衰させている。ブーミーな蓄音機が多いので、低域アッティネータの実験も有効かもしれない。

High-Frequency Pre-Emphasis, “Practical Disc Recording”, by Richard H. Dorf, Gernsback Library No.39, 1948, p.65この最後の箇所で触れられている「あるレコードメーカ」が、具体的にどこのことを指しているのかはわかりません。

I have no idea which record manufacturer was actually “one record manufacturer, for instance” in this paragraph.

そして、ターンオーバー周波数から直接 2.5dB/オクターブスロープにして 8,000Hz で +10dB ブースト(すなわちターンオーバー周波数は 500Hz)、なんていう、極端にシンプルなカーブの存在は知られていません。一方、のちの AES 再生カーブ (1951) においては、8,000Hz で -10dB 減衰、10,000Hz で -12dB 減衰となっていますので、想定する録音時のブーストは 8,000Hz で +10dB、10,000Hz で +12dB となりますので、これに類似したプリエンファシスのことを指しているのかもしれません。

Also, the existence of such simplified pre-emphasis as “2.5dB/octave slope beginning at turnover (500Hz)” and “10dB boost at 8,000Hz” was never known to be used for any shellac records ever produced. One hint is the AES Playback Curve (1951), with -10dB at 8,000Hz and -12dB at 10,000Hz, thus the corresponding recording curve would be +10dB boost at 8,000Hz and +12dB at 10,000Hz. So the author might refer to a certain example of the company that used similar pre-emphasis to the reverse of AES Playback Curve.

おそらく、プロ向けの本格的な専門書ではなく、セミプロ・アマチュア向けの書籍なので、「2.5dB/オクターブスロープ」という表現は不正確ではあるものの、議論を単純化するため、このような表現を便宜上使っただけなのでしょう。

It is highly probable that the author (Mr. Dorf) over-simplified the discussion too much, because this book was not for true professionals but for semi-professional / amateur learners.

ともあれ、1940年代当時から「市販用シェラックレコード向けに」なんらかの高域プリエンファシスが一般的に使われていたことは間違いありません。そしてその使用目的は「フラット再生の一環」ではなく、「リスナーがサーフェスノイズ対策で高域を絞るから、その分強調して記録しておく」だった、ということになります。

Anyway, this description also proves that some sort of high-frequency pre-emphasis was applied in the disc recordings “for commercial shellac records” in the 1940s. Also, the purpose of pre-emphasis was NOT for “flat/uniform/faithful playback”, but just for “compensating a high-frequency loss by attenuators operated by listeners who wanted to enjoy music with less surface-noise”.

だからこそ、当時はレーベルごとにプリエンファシスがバラバラだった(再生側でいうとロールオフ値がバラバラ)のは当然だったと言えるのです。

So it was very natural in the shellac era that the amount of pre-emphasis varied (i.e. “associated roll-off values varied”, from reproducer’s perspective) among the labels.

9.3 Some Implications found in 1940s’ equipments / 1940年代の各種機器から読み取れること

放送局用、すなわちプロフェッショナル用の機器については、カタログ、マニュアル、技術解説記事、論文、など、各種資料が大量に現存しています。一方、当時の市販用・家庭向け再生機器の資料は意外と少ないものです。例えば、どのようなピックアップ(カートリッジ)が使用されていたか、どのような再生補正回路が使われていたか、などを知る手掛かりとなる資料です。

Many catalogs, operating manuals, documentation, technical articles and papers for the professional-use equipments (in broadcasting industry) survives, and are easily accesible. On the other hand, those for home instruments – that surely help understand the schematic circuit diagrams, or the parameters used for compensation – are very hard to find, unfortunately.

9.3.1 “RCA Victor Service Data”, 1938 to 1948

幸いなことに、RCA Victor 製品の保守・整備用サービスマニュアルが残されており、1923年から1952年のものがオンラインで公開されています。これらにより、当時の家庭用再生機器の構成、純正交換部品番号、そして回路図などを参照可能になっています。

A rare exception is a bunch of service manuals for RCA Victor products – many are accessible online, from the oldest 1923 version to the 1952 version. Reading these through will help understand the configuration of such old home instruments, genuine replacement part numbers, and schematic circuit diagrams.

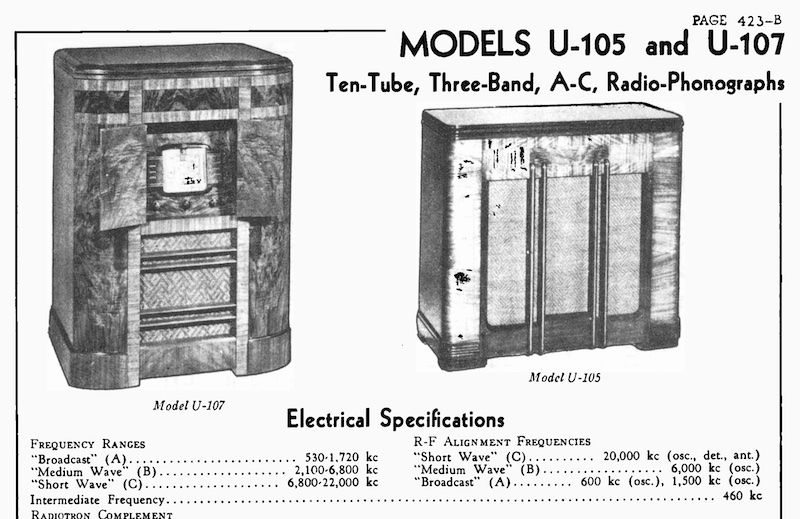

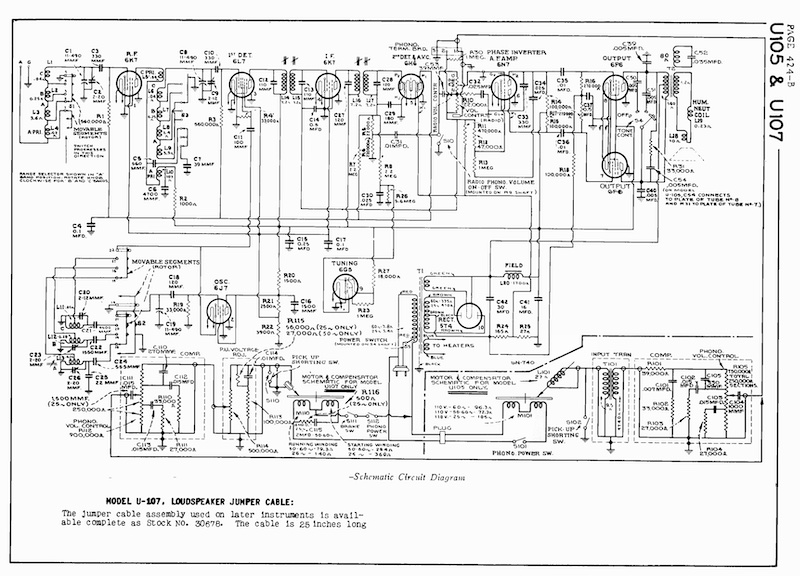

例えば、1932年〜1938年のサービスマニュアル “RCA Victor Service Data” に、1937年頃登場と思われる RCA のラジオ電蓄 U-105 / U-107 というモデルが掲載されています。掲載されたキャビネット写真を見る限り、サイズや作りも全然違うように感じますが、どうやら内部回路は基本的に同一のものを使っていたようであることが分かります。

For example, 1932-1938 edition of the “RCA Victor Service Data” contains the service manual for RCA Radio-Phonograph U-105 / U-107. According to outside appearances, the size and construction of U-105 and U-107 are different, but according to the circuit diagram on the manual, both models basically shared the same circuit.

source: “RCA Service Data 1932-1938 Vol.B”, p.423-B

RCA サービスマニュアルに掲載されたラジオ電蓄 U-105 / U-107 の外観

source: “RCA Service Data 1932-1938 Vol.B”, p.424-B

RCA U-105 / U-107 の回路図

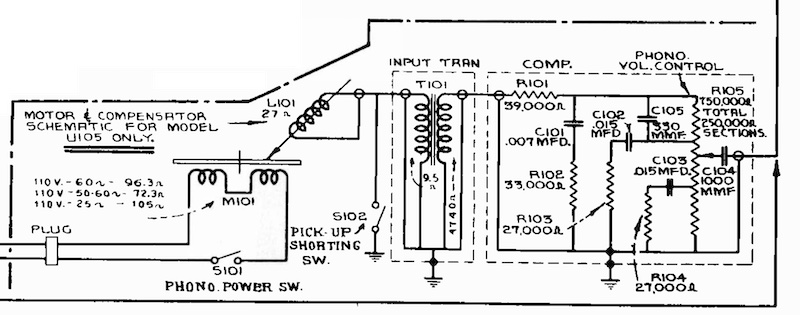

このモデルの回路図をよくみてみると、回路図は共通であるものの、電蓄(レコードプレーヤ)部分の回路が、U-105 と U-107 で異なっていることが分かります。さらにスペックを良くみてみると、U-105 はマグネットカートリッジ、U-107 はクリスタルカートリッジが使われており、フォノイコ部分の回路も異なります。この回路図の右下部分が U-105(マグネットカートリッジ、入力トランス、補正回路)で、左下部分が U-107(クリスタルカートリッジ、電圧調整回路、補正回路)となっています。

A closer inspection of this circuit diagram shows the main difference between U-105 and U-107, around the phonograph player unit and its accompanying circuits. U-105 uses a magnet pickup, while U-107 is attached with a crystal pickup, resulting in the difference of equalization circuits between two models (bottom-right: U-105, bottom-left: U-107).

source: “RCA Service Data 1932-1938 Vol.B”, p.424-B

RCA U-105 (マグネットカートリッジ版) フォノ部分を拡大したもの

source: “RCA Service Data 1932-1938 Vol.B”, p.424-B

RCA U-107 (クリスタルカートリッジ版) フォノ部分を拡大したもの

当然ながら、マグネットカートリッジ版 U-105 でも、クリスタルカートリッジ版 U-107 でも、カーブ補正回路や設定ノブなどは存在せず、基本的には回路図上のアンプ部分にあるトーンコントロールで高域減衰量を調整して、サーフェスノイズの影響を減らしてちょうどいい感じに聴けるように補正していたことが分かります。

Of course, neither U-105 (magnet pickup version) nor U-107 (crystal pickup version) has a variable EQ circuit and its rotary/push adjusters. The sound can be adjusted and compensated with the tone-control on the amplifier unit. Owners of such home phonograph players at the time utilized the “tone-control” knob to control the high frequency attenuation to reduce surface noise for better playback.

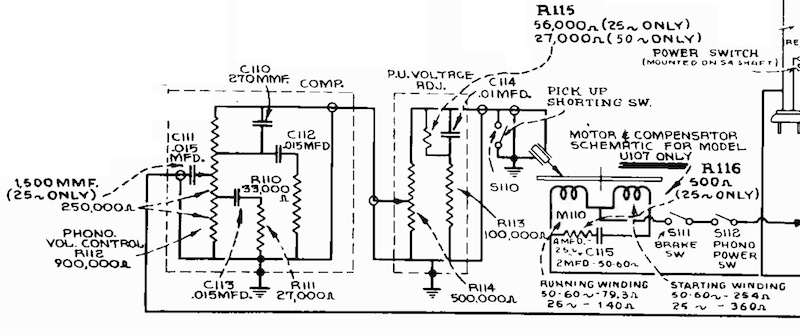

ところで、このサービスマニュアル、1943年〜1946年版 RCA Victor Service Data および 1947年〜1948年版 になると、全てのラジオ電蓄において、クリスタルカートリッジが採用されていることに驚かされます。やはり当時は、家庭用の再生カートリッジとしては、圧電ピックアップが圧倒的にシェアをとっていたことが分かります。それだけ、本稿 Pt.7 でもみたように、出力も大きく、再生補正回路を単純化でき、針圧も軽めにでき、かつ安価に製造可能、というクリスタルカートリッジのメリットが評価されていた、ということでしょう。

By the way, when I read the 1943-1946 edition of RCA Victor Service Data and 1947-1948 edition, I was surprised to know that almost all home phonograph players / radio-phonograph instruments by RCA were equipped with crystal pickups. It shows that piezo-electric pickups had the largest market share of the home audio equipment installation in the 1940s. This is probably because, as we have seen in part 7 of my article, several advantages of crystal pickups – high voltage output, no need of complicated compensation circuit, light needle pressure, and being cheap – were accounted.

source: “RCA Service Data 1943-1946”, p.VIII

RCAの各種電蓄で採用されていたクリスタルピックアップ一覧

更に余談ですが、これらサービスマニュアル群を時代順に追っていくと、「ラジオ」「蓄音機 / 電蓄」が「ラジオ電蓄」となり、さらに「FM/AMラジオ電蓄」へと進化、1947年には「テレビジョン・FM/AMラジオ・電蓄」も登場しているのが、非常に興味深いです。

Another digression here is that, RCA’s home equipment initially started as “Radio” and “Phonograph”, followed by “Radio-Phonograph”, “FM/AM Radio-Phonograph”, and finally in 1947 “Television, FM/AM Radio, Phonograph Combination” was born, which I found very interesting.

source: “RCA Service Data 1947-1948 ”

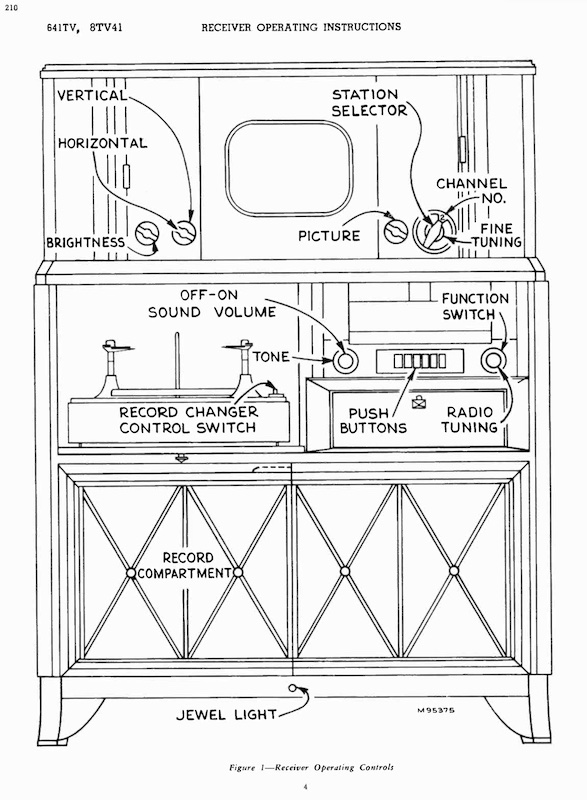

テレビジョン・FM/AMラジオ付きオートチェンジャー電蓄、641TV と 8TV41 の正面から見た操作系説明図

日本でいうところの「ラジオ」「ラジカセ」「ラテカセ」「ラテカピュータ」のことを思い出してしまいました。

It reminds me of the days when I was a lad – there was a “radio”, followed by “radio-casette” (boombox), “radio-television-casette”, and even “radio-television-casette-computer-clock-printer” – all sold in Japan.

【これシャープっぽい製品だなと思ったらRT】“ラジオ+テレビ+カセット+コンピュータ+時計+放電プリンタの6大情報メディアを有機的に結合したパーソナル情報センター”(当時の表現)「ラテカピュータ」1979年 ※カセットはデータと音声記録も pic.twitter.com/uegAen2X

— SHARP シャープ株式会社 (@SHARP_JP) October 30, 2012

9.3.2 “RCA Broadcast Audio Equipments”, 1945 & 1948

では、市販用シェラック盤を再生することもあった、プロフェッショナル現場(=ラジオ放送局)の機器ではどうだったでしょうか。

So, how about the professional equipment at radio stations? Commercial shellac records were also played with transcription turntables.

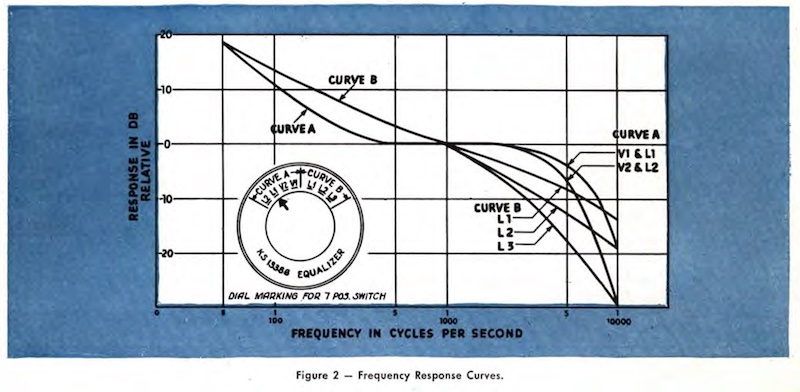

多くのメーカがトランスクリプションターンテーブルを放送局向けに製造・販売していましたが、ここでは RCA の 1945年カタログから、有名な RCA 70 シリーズトランスクリプションターンテーブルの1945年時点での最新モデル、70-C1 をみてみましょう。2スピード(33 1/3rpm, 78rpm)対応、横振動盤と縦振動盤と両対応、16インチの放送局用ターンテーブルです。型番は 60Hz 仕様が MI-4871-C、50Hz 仕様が MI-4872-C となっています。

Various manufacturers developed and marketed transcription turntables for broadcast stations. Among them, here is one example from RCA’s 1945 Catalog – RCA 70-C1, the famous RCA 70 Series Transcription Turntable. It’s a gear-driven 16-inch turntable, compatible with two speeds (33 1/3rpm for electrical transcriptions, 78rpm for commercial records and some transcriptions); compatible both with lateral/vertical-cut records.

source: RCA Broadcast Audio Equipment, 1945, p.51

RCA 70-C1 トランスクリプションターンテーブルの外観

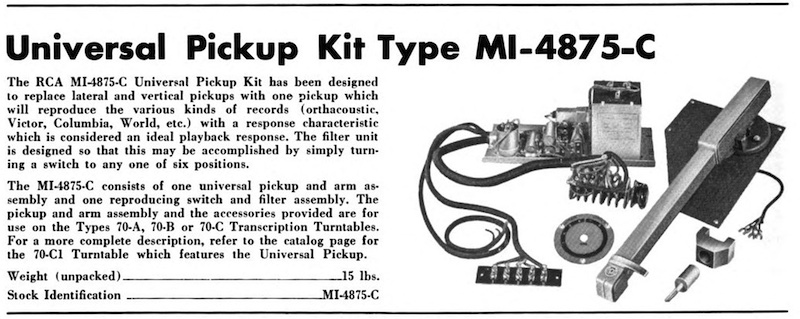

この 70-C1 ターンテーブルは、ピックアップキット(トーンアーム+ピックアップと再生EQユニットのセット)MI-4875-C が組み込まれています。MI-4875-C は縦振動・横振動両対応で 70-A / 70-B / 70-C といった旧式のトランスクリプションターンテーブルに装着するために別売りされていたようです。

This 70-C1 turntable comes with the MI-4875-C pickup kit (tonearm + pickup + playback equalizer unit). This MI-4875-C is compatible both with lateral/vertical, and sold separately for old versions of the 70 Series like 70-A / 70-B / 70-C.

source: RCA Broadcast Audio Equipment, 1945, p.51

RCA 70-C1 トランスクリプションターンテーブルにプリインストールされていた、トーンアーム/ピックアップ/再生イコライザのセット MI-4875-C

source: RCA Broadcast Audio Equipment 1945, p.51

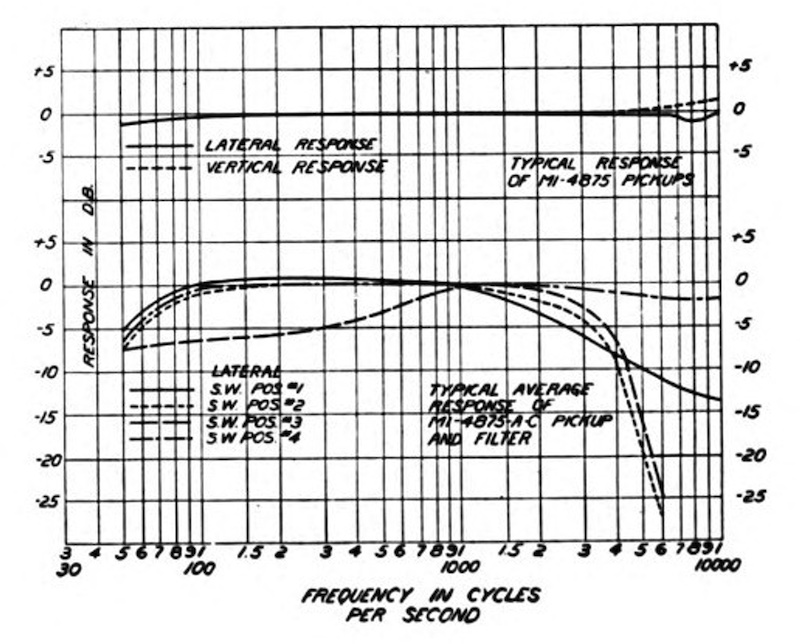

RCA 70-C1 トランスクリプションターンテーブルに組み込まれた MI-4875-C ピックアップキットの内蔵フィルタ(再生イコライザ)を使った際の応答特性

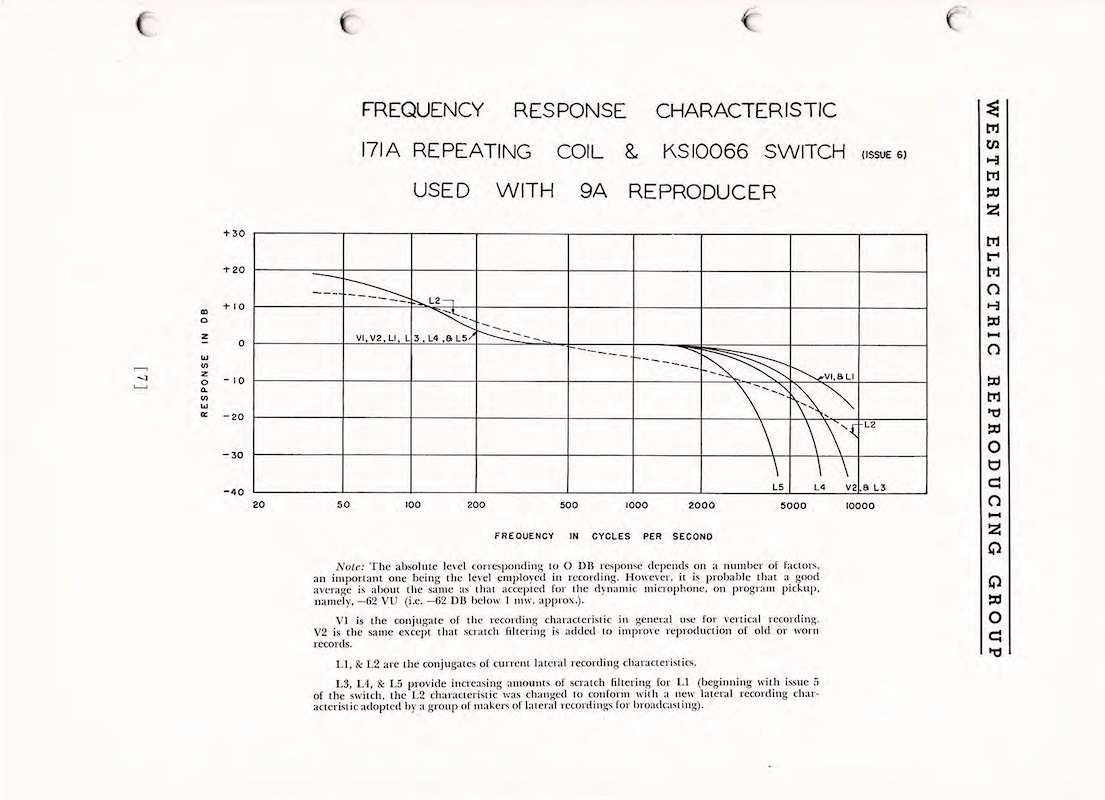

1945年ですから、とっくにNAB規格は策定され、しかもNAB横振動盤記録特性は RCA 自社の Orthacoustic と同一なのに、イコライザポジションSW #1 (トランスクリプション用、Orthacoustic用、Columbia用) の再生カーブは、10,000Hz で -16dB となっていません。-14dB 程度のアッティネーションとなっています。NAB 規格が ±2dB 誤差を許容するので、これでいいということでしょうね。

1942 NAB Standardization was already adopted and spread in 1945, of course. Also, the NAB Lateral Recording Characteristic was the very same as RCA’s Orthacoustic curve. But as you can see above, the graph of equalizer position SW#1 (for transcription discs, Orthacoustic and Columbia) doesn’t read -16dB attenuation at 10,000Hz; about -14dB attenuation instead. This was acceptable, because the NAB Standards permits ±2dB tolerance.

なお、500Hz 以下の低域増幅が全く行われていないように見えるグラフなのが不思議に思われるかもしれませんが、この特性グラフは、いわゆるテストレコード(おそらく、本稿 Pt.3 で紹介した RCA 84522、または、本稿 Pt.5 で紹介した NBC 2346 でしょう)を再生した結果です。つまり、500Hz 以下は 6dB/オクターブの定振幅で記録されていて、500Hz 以上はフラットに定速度で記録されているテストレコードですから、結果として 500Hz 以下が上のグラフのようにほぼフラットになっているのが正しいということになります。

You may think it strange that the below-500Hz range of this graph doesn’t show any bass boost. But it’s correct. This frequency response graph (in velocity basis) was plotted using the frequency test records – probably ones like RCA 84522 (as I mentioned in the part 3 of my article) or NBC 2346 (as I mentioned in the part 5 of my article). Such “frequency test records” contains signals of constant-amplitude (6dB/octave slope) below 500Hz, and constant-velocity (flat) above 500Hz, so the above graph seems proper and correct.

そして、イコライザポジションSW #4 (フラット) というのは、今でいう 500N-FLAT に対してフラット、という意味になります。

And the equalizer position SW#4 (FLAT) means, in the literature of archival variable EQ phono preamps, “500N-FLAT”.

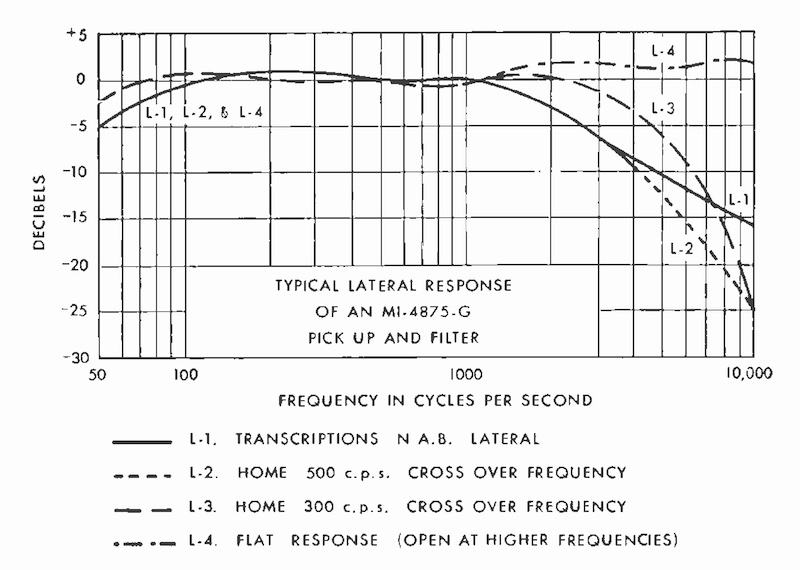

その3年後、1948年のカタログに掲載されている 70-D トランスクリプションターンテーブルの応答特性はどうでしょう。ピックアップキット(トーンアーム+ピックアップと再生EQユニットのセット)は MI-4875-G に変更され、再生周波数特性も 1945年のものから変わっています。

Next is the 70-D in 1948, a direct successor to 70-C1. Included pickup kit (tonearm + pickup + playback equalizer unit) is changed to MI-4875-G, and the frequency response characteristic is slightly different from that of MI-4875-C released in 1945.

source: RCA Broadcast Equipment 1948, p.71

RCA 70-D トランスクリプションターンテーブルに組み込まれた MI-4875-G ピックアップキットの内蔵フィルタ(再生イコライザ)を使った際の応答特性

「L-1」という実線グラフが、NAB 横振動向けカーブと書かれています。確かに、10,000Hz で -16dB となっており、NAB録音カーブの高域プリエンファシスの逆となるロールオフ値になっています。ここでやっと、NAB 録音特性 (500B-16) にほぼぴったり合致した再生イコライザが用意されたことになります。そしてやはりここでも、L-4 の破線グラフが「FLAT」と書かれていますが、500N-FLAT の意味であることが分かります。

The solid line graph “L-1” is labeled “for NAB Lateral Curve”. This time, high frequency de-emphasis slope goes -16dB at 10,000Hz, the very same value as NAB lateral curve (500B-16). So MI-4875-G had more precise NAB playback curve than MI-4875-C did. Again, the dotted line “L-4” is labeled “FLAT”, meaning “500N-FLAT”.

9.3.3 “Pickering 163A Equalizer”, Audio Engineering, June 1948

別の再生用イコライザもみてみましょう。Audio Engineering 誌 1948年6月号に掲載された、ピカリング (Pickering) トランスクリプションターンテーブル向けの 163A イコライザ(再生フォノイコ)の広告です。5種類のカーブがロータリースイッチで選択できるようになっています。

Take a look at other playback equalizers. I found the Ad of Pickering 163A equalizer for Pickering transcription turntables in June 1948 issue of Audio Engineering magazine. It can switch five different playback curves using a dedicated rotary switch.

source: Audio Engineering, June 1948, Vol.32, No.6, p.8

Pickering 163A イコライザの広告

- Flat high frequency response to over 15,000 cycles per second. Low frequency rise to give full compensation from 500 to 40 cycles.

- Flat high frequency response. Low frequency response approximately 5db below position 1.

- For NAB or Orthacoustic transcriptions.