EQカーブの歴史、ディスク録音の歴史を学ぶ本シリーズ。前回 Pt.15 では、こぼれ話的に「ハイ・フィデリティ」という用語の歴史について調べてみました。

On the previous part 15, I studied on the history of the term “High Fidelity (Hi-Fi)” as a side story, before I continue studying more on the history of disc recording and recording / reproducing EQ curves.

今回の Pt.16 は、再び本論に戻り、オーディオ工学に特化した学会の設立、そしてその学会から出された「統一再生カーブ」の提唱、などをみていきます。

This time as Pt. 16, I am going back to continue learning the history of disc recording, including the establishment of an academic society specialized in audio engineering; and the proposed playback curve advocated by that society.

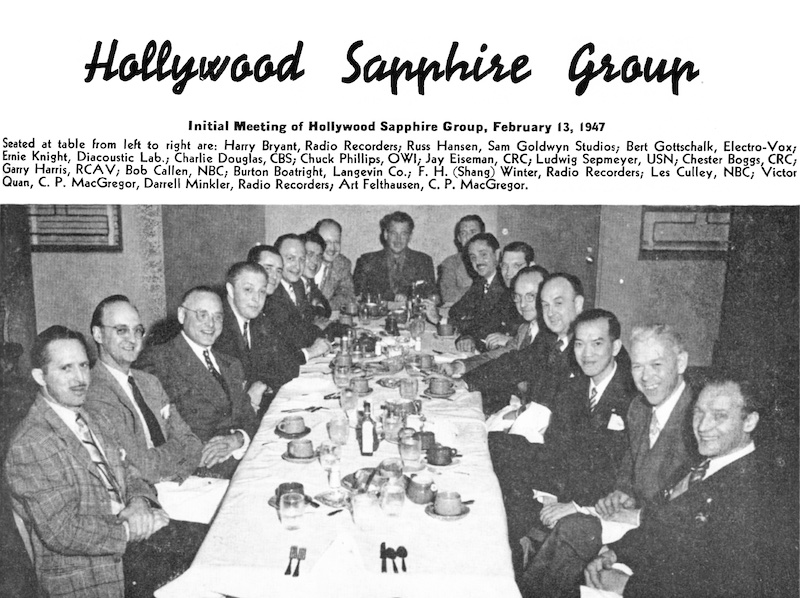

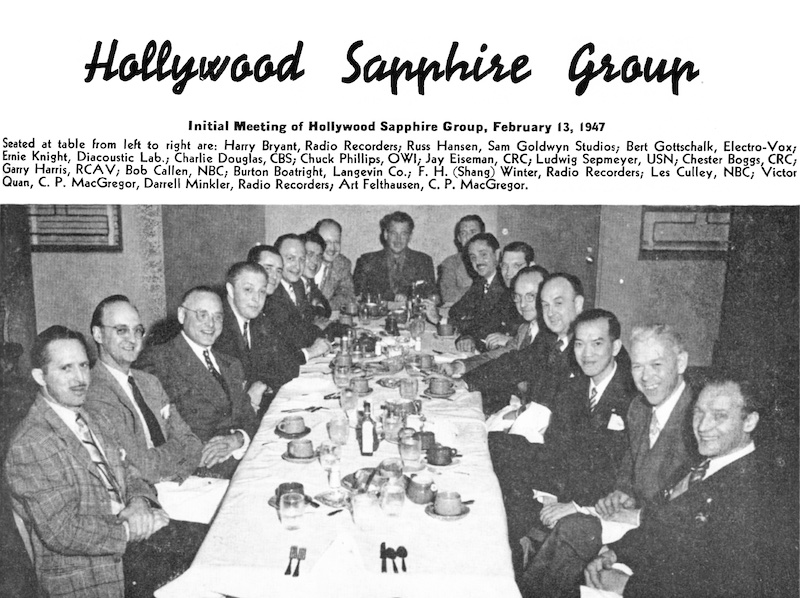

source: “Hollywood Sapphire Group”, Robert J. Callen, Audio Engineering Magazine, Vol.32, No.1, January 1948, pp.17,39-41.

1946年2月13日、Hollywood の Brittingham’s レストランで模様された、Hollywood Sapphire Group の初会合の写真 (写真キャプションの1947年は間違い)

毎回書いている通り、筆者自身の学習過程を記したものですので、間違いの指摘や異論は遠慮なくお寄せください。

As I noted in every part of my article, this is a series of the footsteps of my own learning process, so please let me know if you find any mistakes on my article(s) / if you have different opinions.

今回も相当長い文章になってしまいましたので、さきに要約を掲載します。同じ内容は最後の まとめ にも掲載しています。

Again, this article become very lengthy — so here is the summary of this article (the same contents are avilable also in the the summary subsection).

第二次世界大戦中の物資不足から始まった「サファイア・グループ」という業界エンジニア間の交流により、企業内に閉じていた技術情報のオープンな協働へとつながり、戦後の各種録音再生技術標準化、そしてオーディオ工学専門の学会の設立へとつながった。それらはごく一部のマイナーな動きでは決してなく、オーディオ工学に関わるあらゆるメーカ、レーベル、エンジニア、研究者による大きな流れであった。

The shortage of materials during the The World War II led the formation of “Sapphire Group” activities among professional engineers in the industry, gradually disclosing trade secrets each other, resulting in open collaborations. This enabled the industry (and engineers) to advance toward the standardization of various recording / reproducing technology, as well as the foundation of the society for audio engineering. Such movement was not within a few minor engineers, but a huge leap for the industry, with many manufacturers, labels, engineers and researchers involved.

AES 創立メンバは業界を代表する豪華エンジニア揃いであり、NAB を含め各種学会、各種標準化団体とも連携したり掛け持ちしたりしつつ、オーディオ工学の発展に尽力した。

AES charter members consisted of industry leaders and wizards of audio engineering. They endeavored the collaborations (or did multiple jobs) with other societies and standards associations including NAB, contributing the further development in the audio engineering field.

1950年〜1951年時点では、全てのレコード製造現場に単一の録音特性を強制することはまだ困難があったため、AES 標準化委員会所属の名うてのエンジニア達が、「再生用カーブ」を策定し、各製造レーベルがこのカーブを使って再生されることを念頭にマスタリング(カッティング)してもらおうとした。

At the timing of 1950 and 1951, it was so difficult to let all the record manufacturers to use one unified recording characteristics. So the AES Standards Committee, consisting of leading engineers in the industry, formulated the “Standard Playback Curve”, so that the record manufacturers could master (cut) the discs so that it sounds adequate with this reproducing characteristics.

AES カーブの特性は、当時流通していたさまざまなレコードで使われていた特性の平均値のようなものとなっていた。一方で、高域増幅が過剰であり歪の原因となる、と1940年代からたびたび指摘されていた点の反映もあり、高域ロールオフは浅めに設定されていた。

The AES characteristics is like a compromise (a.k.a. “somewhere in the middle”) among various characteristics already used in the industry. On the other hand, the high-frequency roll-off was weaker than NAB and Columbia, reflecting the long-discussed controversy of “excessive high-frequency pre-emphasis” used in NAB and Columbia, that was one of the reasons of excessive distortion.

Contents / 目次

16.1 Foundation of Audio Engineering Society

今回はまず、初めての標準再生カーブの策定という大きな役割を果たした Audio Enginering 誌、およびオーディオ工学専門の学会 Audio Engineering Society について、その歴史をたどってみましょう。戦前からラジオ技術が主流だった中、オーディオ工学(オーディオ技術)専門の雑誌、および学会の果たした役割は少なくありませんでした。

Next in this part 16, I am going to trace the history of the Audio Engineering magazine, that contributed the formulation of the first playback standard curve; and the Audio Engineering Society, the first academic society specialized in audio engineering. These audio-centered magazine and society did play a huge role while radio electronics had been the centre of the topic since the 1920s.

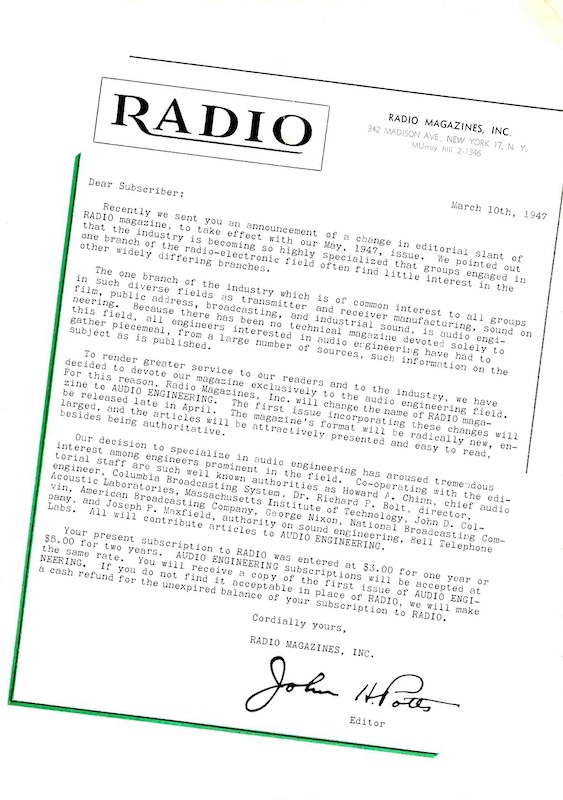

16.1.1 Last issue of “Radio” Magazine (Feb./Mar. 1947)

本稿 Pt.9 セクション 9.2.2 でも紹介した通り、1917年創刊の歴史ある雑誌 Radio が、1947年2/3月号 (Vol. 31, No. 2) を最後に誌名変更をアナウンスし、 1947年5月号 (Vol. 31, No. 3) から Audio Engineering という名前で再スタートすることになりました。

As already mentioned in Pt. 9 Section 9.2.2, the historic magazine Radio (first published in 1917) announced a name change after the Feb./Mar. 1947 issue (Vol. 31, Nol. 2), and restarted under the new name Audio Engineering in the May 1947 issue (Vol. 31, No. 3).

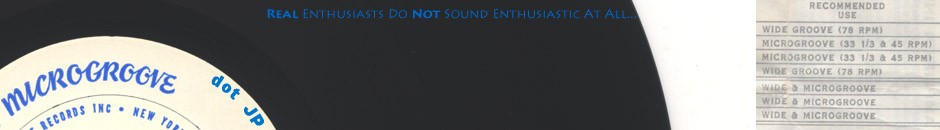

source: RADIO Magazine, Vol. 31, No. 2, February-March 1947,, p.0.

Radio 誌1947年2/3月号の冒頭に掲載された、誌名変更のアナウンス。

Radio 最終号となる 1947年2/3月号 (Vol. 31, No. 2) の編集長コラム「Transients」には、来たる Audio Engineering 誌創刊号に掲載予定の記事および豪華執筆陣について触れられています。

The Editor’s column “Transients” in the last issue of Radio (Feb./Mar. 1947, Vol. 31, No. 2) describes the coming gorgeous articles (by gorgeous authors) to be published in the first issue of the Audio Engineering magazine.

source: “Transients: Announcement”, RADIO Magazine, Vol. 31, No. 2, February-March 1947, p.3.

Many outstanding articles are already scheduled for AUDIO ENGINEERING. For example, Howard A. Chinn writes about magnetic tape recording, Joseph P. Maxfield on microphone placement, Norman C. Pickering on high-quality phonograph pickups, John B. Colvin on audio systems in FM broadcasting, Samuel Milborne on industrial sound, Grieveson and Wiggins on a comparative db meter which greatly simplifies microphone calibration, and many others of similar high caliber. Reviews and abstracts of audio engineering articles appearing in foreign publications will be a special feature of each issue. Also, our regular practice of including a chart to simplify design problems in audio engineering will be continued. In addition, many new features will be added which will be announced later.

来たる Audio Engineering 誌に向けて、すでに多くの優れた記事が準備されている。例えば、Howard A. Chinn 氏の磁気テープ録音に関する記事、Joseph P. Maxfield 氏のマイクロフォンの配置に関する記事、Norman C. Pickering 氏の高品質電蓄ピックアップに関する記事、John B. Colvin 氏の FM放送のオーディオシステムに関する記事、Samuel Milborne 氏の工業用音響についての記事、Grieveson と Wiggins 両氏のマイクロフォン較正を簡単にする比較dBメータに関する記事、その他同様のレベルの高い記事が多く用意されている。海外出版物に掲載されたオーディオ工学の論文のレビューや要約は、毎号の特集として掲載される予定である。また、Radio誌恒例の、オーディオ工学の設計上の問題を簡略化するチャートの掲載も継続する予定である。さらに、新特集も多数追加されるが、これは後日発表される。

“Transients: Announcement”, Radio, Vol. 32, No. 2, February/March 1947, p.3上をみても分かる通り、当時の最先端や大御所だらけの、ものすごい執筆陣です。一方、この予告された中で翌号に実際に掲載されたのは、Chinn 氏の記事、Colvin 氏の記事、Grieveson & Wiggins 両氏の記事だけでした。

As you read the above column, the lineup of the authors is really astonishing, including leading-edge figures. On the other hand, only three articles (by Mr. Chinn; Mr. Colvin; Mr. Griveson & Mr. Wiggins) of above were actually issued on the next issue.

16.1.2 First issue of “Audio Engineering” Magazine (May 1947)

そして、無事 Audio Engineering 誌 1947年5月号が再創刊しました。

And the newly-born Audio Engineering magazine was published peacefully in May 1947.

source: “Transients: Introducing Audio Engineering”, Audio Engineering, Vol. 31, No. 3, May 1947, p.4.

Audio Engineering 創刊号の編集長コラム欄

Audio Engineering 誌の 編集顧問 (Editorial Advisory Board) の顔ぶれが非常に豪華です。全員が著名なエンジニアであり、かつ 1949 NAB 標準規格委員会の執行委員会メンバ、または分科会のプロジェクトメンバです(Pt.10 参照)。

The lineup of the magazine’s Editorial Advisory Board is simply gorgeous: every advisory was (soon to be) deeply related to the NAB Recording and Reproducing Standards (executive committee member or project group member) (see also: Pt.10).

そして、Columbia の親会社 CBS、そして RCA 系の NBC / ABC 、すなわちレコード業界の2大巨頭も関わっていることになります。

Furthermore, CBS was a parent company of Columbia, and NBC / ABC were originally under RCA — two record giants (RCA and Columbia) appear here again.

| Name | Belonging (as of May 1947) | (Notes) |

|---|---|---|

| Howard A. Chinn | Columbia Broadcasting Systems (CBS) | 1949 NAB Standards Executive Committee |

| John D. Colvin | American Broadcasting Company (ABC) | 1949 NAB Standards Executive Committee |

| C. J. LeBel | Audio Devices, Inc. | 1949 NAB Standards Project Groups A & B |

| J. P. Maxfield | Bell Telephone Laboratories | (inventor of “rubberline” recording system) |

| George M. Nixon | National Broadcasting Company (NBC) | 1949 NAB Standards Executive Committee |

source: Audio Engineering, Vol. 31, No. 3, May 1947, p.1.

Audio Engineering 創刊号目次に掲載された、編集陣と編集顧問陣の顔ぶれ

1920年代〜1940年代中頃までは、研究者や専門家の間でもラジオ技術(更には来るべきテレビ技術開発)の方が活発に議論されており、オーディオ工学はその一部といった位置付けでしたが、戦後のタイミングで、ラジオ受信やディスク再生も含めた「オーディオ工学(オーディオ技術)」という独立した括りの専門雑誌ができたことは大きかったようです。

Especially during the 1920s to mid-1940s, Radio technology (as well as Television technology development) had been primary topic among researchers and experts — audio engineering was just a part of them. But around the mid-1940s, audio engineering was gradually considered as an independent field, and the publication of “Audio Engineering” meant a lot to those who had long been working in the field.

また同時に、オーディオ工学専門家やプロのオーディオエンジニアのみならず、趣味としてオーディオに熱狂するアマチュアホビイストも多くひきつけることになりました。いまでいう「オーディオマニア」「オーディオファイル」のはしり、ということですね。1948年6月号の編集長コラムには、下のように書かれています。

Also, the audio-centered magazine attracted not only experts in audio engineering and professional audio engineers, but also amateur hobbiests — who later became known as “audio enthusiasts” or “audiophiles”. The Editor’s Note in the June 1948 issue of the Audio Engineering magazine reads:

ALTHOUGH this magazine is published by and for audio engineers, we find that our policy of presenting practical articles, rather than highly mathematical, abstruse material, is attracting an ever-increasing number of readers for whom high-quality audio reproduction is sorely a hobby. While most radio engineers automatically fall into this category, there are quite a number of other professional men, such as lawyers, doctors, etc., whose enthusiasm for better audio has encouraged them to make an intensive study of our field. As a result, many who are not engineers have been able to make useful contribution to this art.

本誌は、オーディオ技術者によって、オーディオ技術者向けに発行されているが、高度に数学的で難解な内容ではなく、実用的な記事を掲載する、という本誌の方針が、高品質オーディオ再生を趣味とする読者をますますひきつけていることに気づいた。ラジオ技術者の多くはこのカテゴリに入るが、弁護士や医師など、より高品質なオーディオを求める熱意のもと、この分野を集中して研究するようになった人々も少なくない。その結果、多くの非エンジニアが、このオーディオ工学分野に有益な貢献を行えるようになった。

“Editor's Report: Audio Hobbyists”, Audio Engineering, Vol. 32, No. 6, June 1948, p.616.1.3 Time for an Audio Engineering Society?

この Audio Engineering 誌が創刊されたことで、ラジオやテレビの音声、映画音声に限定しない、広い意味での「オーディオ工学」に特化した学会の設立、ひいては論文を投稿できる「オーディオ工学」に特化した論文誌の誕生が、ますます待望されるようになります。

With the launch of the Audio Engineering magazine, it had become increasingly anticipated to establish a society dedicated to “audio engineering” in the broadest sense — not limited to radio, TV sound and film sound. Also, by extension, a journal dedicated to “audio engineering” to which audio engineering papers can be submitted has become eagerly anticipated.

既存のアカデミックな研究学会としては、ASA (Acousitical Society of America, アメリカ音響学会)、SMPE (Society of Motion Picture Engineers, アメリカ映画技術者協会)、IRE (Institute of Radio Engineers, 無線学会)、AIEE (American Institute of Electrical Engineers, アメリカ電気学会) があり、オーディオや録音再生技術に関する論文も、これらの学会誌に投稿され掲載されていました。また、各レコード会社に所属するチーフエンジニアなどの中には、これらの学会に所属し、論文を発表したりする方もいました。

Relevant existing academic research societies included ASA (Acousitical Society of America), SMPE (Society of Motion Picture Engineers), IRE (Institute of Radio Engineers), AIEE (American Institute of Electrical Engineers); and many audio engineering papers (as well as recording / reproducing technology papers) had been posted and published in their journals/proceedings. Many chief engineers of record manufacturers belonged to these societies, and submitted academic papers.

Audio Engineering Society 誕生の最初のきっかけとなったのは、1947年12月号に掲載された、Frank E. Sherry, Jr. という人の読者投稿でした。

The initial impetus for the birth of the Audio Engineering Society came from a reader’s letter in the Dec. 1949 issue, written by a person named Frank E. Shelly, Jr.

source: “Letters: Audio Association?, by Frank E. Sherry, Jr.”, Audio Engineering, Vol. 31, No. 11, p.3.

Sir:

拝啓

After receiving the first few issues of your new magazine, I must say that I believe you are serving a much neglected field, in a highly adequate manner.

(新しく Audio Engineering 誌となって)最初の数号を受け取ってきて、私はこう言わざるを得ません。当誌担当者の皆さんは、これまで無視されてきた(オーディオ工学という)分野において、非常に適切な方法で、素晴らしく貢献してくださっています。

Now that the audio engineer has been dignified by a specialized publication, which will tend to draw the members of the field together, is it not time for him to have an organization of his own?

オーディオエンジニアがこの専門誌によってオーディオ工学専門家としての尊厳と権威を持てるようになり、この分野のメンバが集えるようになった今こそ、オーディオ工学専門家のための組織を持つべき時なのではないでしょうか。

I have in mind an association similar in function and purpose to the I.R.E. and S.M.P.E. in their respective fields.

私は、IRE (アメリカ音響学会) や SMPE (アメリカ映画技術者協会) がそれぞれの分野で果たしているような、同様の機能と目的を持つ(オーディオ工学専門の)学会のことを考えています。

I will be glad to correspond with anyone interested in this matter.

私は、この件に興味を持たれた方と、喜んでやりとりをさせていただきます。

“Letters: Audio Association?”, by Frank E. Sherry, Jr. Audio Engineering, Vol. 31, No. 11, p.3これを受けて、続く1948年1月号の読者投稿欄には、Audio Devices 社の創業者 C.J. LeBel 氏が投稿します。

This was followed in the January 1948 issue by a contribution from C.J. LeBel, founder of Audio Devices, Inc.

source: “Letters: Audio Engineering Society”, Audio Engineering, Vol. 32, No. 1, p.5.

Sir:

拝啓

In the last issue Mr. Frank E. Sherry, Jr., suggested that audio engineering had grown to the point where it needed a professional society of its own.

前号(の読者投稿欄)で、Frank E. Sherry, Jr. 氏が、オーディオ工学の分野は、独立した専門の学会を必要とするほど成長してきた、と示唆しました。

A group of us, long active in broadcasting and recording, feel the same way he does. Audio engineering will be unhampered only when it has a society devoted exclusively to its needs — controlled by, and run only to benefit, the audio engineer.

放送や録音に長らく携わってきた我々も、Sherry 氏と同様に感じています。オーディオエンジニアによって管理され、オーディオエンジニアのために運営される、そのようなニーズに特化した協会、学会をもつことによってのみ、オーディオ工学は何者にも妨げられない存在たりえるのです。

We have been discussing this matter for several months, and are preparing to hold an organization meeting.

我々は数ヶ月前からこの問題について議論し、組織的な会合を開くべく準備を行なっているところです。

Will those interested in such a society please write the undersigned, giving the following information:

このような協会・学会に興味がある方は、以下の情報を添えて、下の署名にある住所まで手紙をお送りください。

氏名

住所

会社名

肩書、または仕事内容

We will notify you of the meeting date.

(お送りいただいた方には)会議の日時をお知らせします。

“Letters: Audio Association?”, by Frank E. Sherry, Jr. Audio Engineering, Vol. 32, No. 1, p.3この一連の読者投稿について、興味深い指摘があります。

By the way, something interesting is pointed out about these reader’s letters.

Susan Schmidt Horning 氏の書籍 “Chasing Sound: Technology, Culture, and the Art of Studio Recording from Edison to the LP” (2013, The John Hopkins University Press) の中で、この Shelly 氏の投稿に関するエピソードも出てくるのですが、その脚注にさらっとすごいことが書かれていました。Audio Devices 社の C.J. LeBel 氏が、学会設立の動きを加速させるために、自作自演した可能性が高い、というのです(笑)

In the Susan Schmidt Horning’s book “Chasing Sound: Technology, Culture, and the Art of Studio Recording from Edison to the LP” (2013, The John Hopkins University Press), the letter from Frank E. Shelly Jr. and the reply letter from C.J. LeBel were also featured, but its footnote says it all in a nutshell.

According to more than one source, this letter, signed by Frank E. Sherry, Jr. was “a fake” to get things going and quite possibly was written by C.J. LeBel, but subsequent events proved that the undercurrent of interest existed. No “Frank Shery” appears on the roster of the first meetings or the first official membership directory.

複数の情報源によると、Frank E. Sherry, Jr. 氏の署名入りのこの投稿は、(学会設立に向けて)物事を進めるための「捏造」であり、C.J. LeBel 氏が書いた自作自演の可能性が非常に高いが、(この投稿に続く)一連の流れで、学会設立に関する関心が水面下で進んでいたことが証明された。ちなみに「Frank Sherry」という名前は、最初の会合の名簿にも、最初のAES公式会員名簿にも登場しない。

“Chasing Sound: Technology, Culture, and the Art of Recording from Edison to the LP”, pp.241-242, by Susan Schmidt Horning, The John Hopkins University Press, 201316.1.4 The Audio Engineering Society is Formed

そして、この LeBel 氏の投稿の前後(おそらく前)、1948年1月8日に、最初の小規模の会合が持たれ、運営委員会 (steering committee) が選出されました。

And on January 8, 1948, before (or after) LeBel’s reply letter, the first small meeting was held, and a steering committee was elected.

1948年2月17日にはニューヨークの RCA Victor 録音スタジオ (East 24th St.) で2回目の会合が開かれ、噂をききつけた録音エンジニア、発明者、ミュージシャン、オーディオ機器製造業者、オーディオ専門家、アマチュア愛好家など137人もが集結したとのことです。その面々は、企業を超え、業界を超え、錚々たるものだったようです。

The second meeting was held on February 17, 1948, at RCA Victor Recording Studio (East 24th St.), where 137 recording engineers, inventors, musicians, audio equipment manufacturers, audio professionals, amateur enthusiasts gathered after hearing a rumor. The group were made up of people from different companies, industries, and professions — apparently distinguished by its transcendence of business and industry.

The group (of those present at the Feb. 17, 1948 second meeting) included millionaire inventor and entrepreneur Sherman M. Fairchild, record reviewer Edward Tatnall Canby, stylus manufacturer Isabel Capps, lathe manufacturers Lawrence Scully and George Saliba, inventor Emory Cook, musicians Les Paul and Fred Van Eps, and recording engineers representing every major label, including Al Pulley of RCA, Bob Fine of Mercury, Clair Krepps from Capitol, and Vincent Liebler from Columbia. Collectively, they composed the first association dedicated to filling a desperate need for “the promulgation of engineering information and standards in the field of recording, transmission, and reproduction of sound.

(1948年2月17日の第2会合に集まった)面々には、億万長者の発明家にして起業家の Sherman M. Fairchild 氏、レコード評論家の Edward Tatnall Camby 氏、レコード再生針製造メーカの Isabel Capps 氏、カッティングレース製造メーカの Lawrence Scully 氏および George Saliba (Presto) 氏、発明家の Emory Cook 氏、ミュージシャンの Les Paul 氏および Fred Van Eps 氏などが含まれた。更に、RCA の Al Pulley 氏、Mercury の Bob Fine 氏、Capitol の Clair Krepps 氏、Columbia の Vincent Liebler 氏、と、各メジャーレーベルを代表して各録音エンジニアも参加していた。参加したメンバは、「音の記録/伝送/再生という分野におけるエンジニアリング情報の普及、および標準規格の普及」という切実なニーズを満たす、初の協会を設立したのである。

“Chasing Sound: Technology, Culture, and the Art of Recording from Edison to the LP”, p.74, by Susan Scmidt Horning, The John Hopkins University Press, 2013確かに、ここに記されただけでも、当時のオーディオ技術や録音エンジニアリングを代表する、著名な名前が並んでいます。上記の書籍によると、137名全員の名簿は、Voice of America 局のスタジオエンジニア Jack Hartley 氏(1923-2003, AES 創設メンバのひとり)が所有するタイプライターによる非公開手打ち名簿で確認された、とのことです。

Indeed, the lineup here consisted of prominent names, representing audio technology and audio engineering of the time. The full list of 137 attendees at the second meeting were confirmed, according to Ms. Susan Schmidt Horning’s book, by the hand-typed private list of attendees owned by Jack Heartley, who was a charter member of the AES, and who worked at the recording studio of the Voice of America station.

Sherman M. Fairchild 氏はもちろん、カッターヘッドやカッティングレースで有名な Fairchild Recording Equipment Corporation の創業者。

Sherman M. Fairchild, of course, was a founder of Fairchild Recording Equipment Corporation, best known for its cutterheads and cutting lathes.

Edward Tatnall Camby 氏は、Audio Engineering 誌を含め雑誌等でレコード評やオーディオ評を書いていた評論家で、Pt.13 セクション 13.1.1 で Billboard の記者 Joe Csida 氏が槍玉に挙げていた(笑)人物。

Edward Tatnall Camby, a record/audio critic who wrote articles in many magazines and papers (including Audio Engineering magazine), and who was criticized by The Billboard’s editor Joe Csida (see: Pt. 13 Section 13.1.1).

Isabel Capps 氏は、ディスク録音カッター針の発明・開発・製造者として有名な、偉大なる Frank L. Capps 氏 (1869-1943) の娘にして、当時の Frank L. Capps and Co., Inc. の社長。1949年NAB規格策定時のプロジェクトグループA (記録溝の形状、および再生針の形状) 小委員会のメンバでもありました。

Isabel Capps, a daughter of the great Frank L. Capps (1869-1943) who was a famous inventor, developer and manufacturer of disc cutter styli, was a president of Frank L. Capps and Co., Inc. at the time. She was also a member of 1949 NAB Standards Project Group A (recorded groove shape; reproducer stylus contour).

Lawrence Scully 氏は、言わずと知れたカッティングレースの Scully Recording Instrument 創業者の息子。

Lawrence Scully was a son of the founder of the well-known Scully Recording Instrument, a distinguished cutting-lathe manufacturer.

George Saliba 氏は、即時録音再生機(アセテート録音機)で有名な Presto Recording Corporation の共同創業者(Pt. 6 参照)。

George Saliba was a co-founder of the Presto Recording Corporation, best known for its instantaneous disc recorders (see: Pt. 6).

Emory Cook 氏は、のちにバイノーラルレコードを出すなど革新的な技術・機器開発で有名な録音エンジニア。ちなみに AES ジャーナル(論文誌)Vol.1 No.1 (1953) の一番最初に掲載された論文は、まさにこの Cook 氏の “Binaural Disc Recording” でした。

Emory Cook, a famous recording engineer of his revolutionary technology development including the invention of the “binaural stereo records”. By the way, the very first paper in the very first issue of the Journal of the Audio Engineering Society (Vol. 1, No. 1, 1953) was authored by Mr. Cook himself, and the paper’s title was “Binaural Disc Recording”.

Les Paul 氏と Fred Van Eps 氏は、ご存知の通り、録音技術の可能性を追求していた、当時を代表するミュージシャン。

Les Paul and Fred Van Eps were, as you may know, two of the leading musicins of their time who were exploring the possibilities of recording technology.

さらに、RCA (Victor) の Albert Pulley 氏は、RCA 録音部門のチーフエンジニアで、RCA Victor における全録音を統括していた人物です。1945年前後の状況を扱った Pt.9 でも、Pulley 氏の名前は登場していました。

Along comes the name of Albert Pulley, chief engineer of RCA Recording Department, who supervised the entire recording at RCA Victor at the time. His name also appears in the Pt.9 of my entire article, that deals with the situation in the mid-1940s.

Capitol の Clair Krepps 氏は、あの Miles Davis の “Birth of the Cool” セッションで録音エンジニアを務めた人で、のちに MGM に移籍してチーフエンジニアとなり、最初期の Pultec EQP-1 をスタジオで使用したエンジニアの1人としても有名です。

Capitol’s Clair Krepps was known as an recording engineer who conducted Miles Davis’ “Birth of the Cool” session. He later moved to MGM as a chief engineer. He is also known as one of the first professional engineers who used Pultec EQP-1.

Columbia の Vincent Liebler 氏は、Pt. 11 セクション 11.2.5 で紹介した通り、ARC 時代に Robert Johnson の Vocalion録音を行ったベテランエンジニアで、Columbia LP 開発に携わった1人で、当時は Columbia の録音部門ディレクタでした。のちに1949年NAB規格のプロジェクトグループG(ラッカー録音盤)小委員会メンバも務めます。

Columbia’s Vincent Lieber, who already appears in Pt. 11 Section 11.2.5, was a veteran engineer who conducted Robert Johnson’s legendary Vocalian recordings in 1936, and he became a director of Columbia’s recording department. He was also a member of the NAB Standards Project G (lacquer recording blanks).

Bob Fine (C. Robert Fine) 氏は、いうまでもなく、のちに Fine Sound Studios および Fine Recording Studios を設立した、Mercury Living Presence で有名な録音エンジニアです。ここでは Mercury を代表すると書かれてはいますが、1948年当時は Mercury が頻繁に使っていた Reeves Sound Studios 専属エンジニアでした。

Bob Fine a.k.a. C. Robert Fine was, needless to say, a legendary recording engineer who later founded Fine Sound Studios and Fine Recording Engineers, best known for his works of Mercury Living Presence. Although this article mentions him as a representative of Mercury, he was a recording engineer at the Reeves Sound Studios at the time of 1948.

余談ですが、当時の3大メジャー (RCA Victor, Columbia, Decca) および 2大セミメジャー (Capitol, Mercury) の中で、唯一自社専用録音スタジオを持っていなかったのが Mercury です(編集やカッティング専門の Mercury Sound Studios は1948年から所有していましたが)。

おそらく “Chasing Sound” の筆者が、のちに Mercury Living Presence を語る上で絶対に欠かせない Fine 氏の名前を見つけて、5大メジャー (3大メジャー + 2大セミメジャー) という視点から書いてしまったものと思われます。

あるいは、可能性は低そうですが、専属録音エンジニアのいなかった Mercury が、Fine 氏に出席をお願いしたのかもしれません。

ともあれ、Audio Engineering Society は設立されました。初代会長は C.J. LeBel 氏でした。

Anyway, in 1948, the Audio Engineering Society was established, with the first chairman being C.J. LeBel.

source: “The Audio Engineering Society is Formed”, L. Goodfriend, Audio Engineering, Vol. 32, No. 3, March 1948, p.16

Audio Engineering 1948年3月号に掲載された、AES 設立を伝える記事

さらに、1949年8月号からは、Audio Engineering 誌のいちセクションとして “The Journal of the AUDIO engineering society” が掲載されるようになりました。技術論文も当セクションに掲載され、のちの1953年に論文誌 “The Journal of Audio Engineering Society” として独立するまで、アマチュアオーディオ愛好家とプロのオーディオエンジニア、オーディオ工学研究者の全てに向けた雑誌として機能しました。

Furthermore, since August 1949 issue, the Audio Engineering magazine had a section dedicated to the society, entitled “The Journal of the AUDIO engineering society”. The section included technical papers, and it played an important role for the society members as well as for amateur enthusiasts, professional engineers and audio engineering researchers, until the section became an independent journal called “The Journal of Audio Engineering Society” in 1953.

source: “Editor’s Report: The New Journal”, Audio Engineering, Vol.33, No.8, August 1949, p.6.

Audio Engineering誌内に学会ジャーナルセクションを設立、論文掲載していくことを報告する、編集長コラム

source: “The Journal of The Audio Engineering Society Section”, Audio Engineering, Vol.32, No.8, August 1948, p.22.

Audio Engineering 誌に1948年8月号に初めて掲載された学会ジャーナルセクション

そして、これら Audio Engineering 誌時代の AES ジャーナルセクション、および掲載された論文は、のちに「Volume 0」と呼ばれることになります。この AES (Audio Engineering Society) 最初期の歴史は、AES の web サイト上の特別ページ「How the AES Began」としてまとめられています。

“The Journal of the Audio Engineering Society” section perid, as well as the papers published in the section, would later be called as “Volume 0”. Such early history is summarized in a dedicated page on the AES website entitled “How the AES Began” as shown below.

1951年4月20日付の AES 会員名簿も公開されており、目も眩むほど豪華な顔ぶれを確認できるほか、研究学会として多くの学生会員も登録していたことが確認できます。

The AES membership list, dated April 20, 1951, is also available, and shows a dazzling list of faces, as well as the fact that as a research society, many student members were also registered.

特に第二次大戦前は、どのレコード製造メーカもレーベルも、スタジオにおける録音再生技術を門外不出にし、ライバル同士で技術競争を行っていましたが、それがために、ラジオ局現場やレコード購買者を無駄に混乱させていました。

Especially before the WWII, all record manufacturers and labels kept recording/reproducing technology strictly confidential, rivals competing each other, which needlessly had confused the radio stations and record buyers.

Audio Engineering 誌の創刊、そして AES というアカデミックな団体が創設されることで、レコード録音再生技術を含めた「オーディオ工学」という分野が確立し、レコードレーベルや企業の壁を超えて、技術的工学的な情報をアカデミックの場で交換し、民主的かつ建設的に運営されるようになった、と言えます。その上で、Audio Engineering 誌と Audio Engineering Society の果たした役割は本当に大きいものがありました。

However, the first publication of Audio Engineering magazine and the founding of the Audio Engineering Society led to the establishment of the “Audio Engineering” field, as well as open discussion and standardization of technological/engineering expertise, in democratic and custructive manner. That definitely was the primary contribution of Audio Engineering magazine and Audio Engineering Society.

16.2 “Sapphire Group” before the AES

このように、「オーディオ工学」という分野を確立し、のちに録音再生技術の標準化に大きな役割を果たすことになる団体 AES ですが、、実はこの流れにはさらに源流があった、その名も「サファイア・グループ」という、秘密結社のような(笑)名称の会合が、1940年代から行われていた、というのが、このセクションで扱う内容です。

AES, the organization that established the field of “audio engineering” and would later play one of the major roles in standardizing recording and reproducing technology, actually had its origins in a secret society-like meetings called the “Sapphire Group” in the 1940s.

このグループ会合こそが、Audio Engineering 誌の創刊や、Audio Engineering Society 設立に先んじて、企業間の秘密主義を超えて、ディスク録音再生技術をオープンに議論し、標準規格策定に向かうことになった最大のきっかけでした。

These group meetings were the primary catalyst for moving beyond corporate secrecy to open discussion of disc recording and reproducing technology, and the development of standards that preceded the founding of Audio Engineering magazine and the Audio Engineering Society.

「サファイア・グループ」のヒストリーは、以下を含むいくつかの記事や書籍で解説されてきました。以下、それらをベースとして、ざっくり歴史を追ってみましょう。

Following articles and books describe the history and reminiscence of the “Sapphire Group”. And the following subsections will cover the summary of these.

16.2.1 New York Sapphire Group

1942年頃、第二次世界大戦突入後、レコード製造に欠かせないシェラック(ラックカイガラムシの析出物、主にインドから輸入)や、モンタンワックス(鉱物系ロウ、主に中央ヨーロッパから輸入)、そしてラッカー原盤製造に欠かせないアルミニウムなどの輸入が滞り、また真空管も戦時供出の対象となったことで、各レコード製造メーカ(レーベル)は危機を迎えていました。

Around 1942, after the outbreak of WWII, imports of shellac (a precipitate of the lac bug, imported mainly from India), montan wax (a mineral wax, imported mainly from Central Europe), and alminium (essential for manufacturing lacquer discs) were delayed, and vacuum tubes were also subject to wartime expropriation. As a result, record manufacturers (labels) were facing a crisis.

そこで1942年頃、各社の録音エンジニアが小規模の会合を開くようになり、ラッカー盤や真空管の余剰分を互いに融通しあうようになったそうです。この会合は毎月第三水曜日にニューヨークのアトランティック・クラブで夕食会として開かれるようになり、会合は録音針の材質からとって「サファイア・グループ」(または「サファイア・クラブ」)と名付けられました。たまに技術的な話も雑談程度に行われていたそうですが、主として業界のエンジニアの社交場として機能していたそうです。

So around 1942, recording engineers from various companies began to meet on a small scale to exchange surplus lacquer discs and tubes with each other. These meetings began to be held on the third Wednesday of each month as a dinner meeting at the Atlantic Club in New York City, and the meetings were named the “Sapphire Group” (or “Sapphire Club”), after the material of the recording styli. Although technical discussions were occasionally held, it mainly functioned as a social gathering for engineers in the industry.

もともと、1940年代前半に、Frank L. Capps and Co. Inc. の W.H. Rose 氏、NBC 録音部門の G.E. Stewart 氏、Columbia Recording Corporation の Vincent Liebler 氏が、たまに昼食会を開いていたそうです。この小規模の会合が、サファイア・グループの源流になったとされています。

It is known that originally in the early 1940s, W.H. Rose (of Frank L. Capps and Co., Inc), G.E. Stewart (of the NBC Recording Division), and Vincent Liever (of Columbia Recording Corporation) had occasional luncheons. This small meeting is said to have been the origin of the Sapphire Group.

ともあれ、秘密主義が徹底されていた当時の録音業界において、第二次世界大戦の原料不足がきっかけとはいえ、企業間の連携が始まるようになったのです。

At any rate, in the recording industry at that time, where secrecy was thoroughly enforced, collaboration among companies began to take place, albeit triggered by the shortage of raw materials during the WWII.

It might be well to note that up until these hard times of dwindling supplies, there was very little communication between company managements. Audio recording was a corporate closed shop. Macy’s did not tell Gimbels. Victor did not tell Columbia. Secrecy prevailed… until rationing and shortages forced cooperation. Necessity became the true mother of invention.

しかし、(レコード製造に必要な)資源不足という大変な時期になるまで、会社経営者同士のコミュニケーションはほとんどなかったという。オーディオ録音の分野は、各企業内で秘密裏に行われいていた。メイシーズはジンベルズに言わなかった(注: 共に当時のマンハッタンの2大デパートで、互いに販売戦略を秘密裏にしていたことで、この慣用句がある)。そして Victor は Columbia に言わなかった。配給や物資不足により協力せざるを得なくなるまで、秘密主義がまかり通っていたのである。つまり、「必要は発明の母」だったのである。

“Reminiscences on the Founding and Development of the Society”, by Donald J. Plunkett, Journal of Audio Engineering Society, Vol. 46, No. 1/2, Jan./Feb. 1998, pp.5-616.2.2 Hollywood Sapphire Group

この会員制の会合「サファイア・グループ」は広がりをみせ、会員数が100名に近づいたところで、西海岸からはるばる参加していた8名のエンジニアが、西海岸に「ハリウッド・サファイア・グループ」を設立し、毎月第2水曜日に会合が持たれるようになりました。初会合は1946年2月13日にハリウッドのコロムビアスクエアにある Brittingham’s レストランで行われたそうです。

This membership meeting “Sapphire Group” began to expand, and when the number of members approached 100, eight engineers who had traveled all the way from the West Coast established the West Coast branch “Hollywood Sapphire Group”, which met on the second Wednesday of each month. The first meeting was held on February 13, 1946 at Brittingham’s Restaurant on Columbia Square in Hollywood.

source: “Hollywood Sapphire Group”, Robert J. Callen, Audio Engineering Magazine, Vol.32, No.1, January 1948, pp.17,39-41.

1946年2月13日、Hollywood の Brittingham’s レストランで模様された、Hollywood Sapphire Group の初会合の写真 (写真キャプションの1947年は間違い)

ハリウッド・サファイア・グループは当初、主に(ニューヨーク・サファイア・クラブのように)社交・ビジネスを主とした場とするか、それとも、主に技術的な議論を行う場とするか、それとも両者をともに行うか、の議論が行われたそうですが、次第に社交としてのディナーミーティングの中でインフォーマルに技術談義が活発に行われる、ユニークかつ民主的な組織として機能し、定着していったそうです。

Initially, the Hollywood Sapphire Group debated whether to be primarily a social and business forum (like the New York Sapphire Group), or a forum for primarily technical discussions, or both. Gradually, the group functioned and took root as a unique and democratic organization, with informal technical discussions taking place during social dinner meetings.

その中から、「ディスク録音における標準規格の必要性」についても活発な議論が行われるようになり、Altec-Lansing 社のチーフエンジニア John Hillard が(ハリウッド・サファイア・グループ内の)録音標準規格委員会の委員長に選出されました。

Then the need for “standardization for disc recording” became a topic of lively discussion, and Altec-Lansing’s chief engineer John Hillard was elected as a chairman of the Recording Standards Committee within the Hollywood Sapphire Group.

複数の小委員会での作業ののち、IRE (Institute of Radio Engineers, 無線学会), ASA (Acousitical Standards Association, アメリカ規格協会), RMA (Radio Manufacturers Association, 無線機器製造業者協会) の会員とも連携しながら、ディスク録音標準規格の策定に尽力したそうです。これらがのちの 1949年NAB規格にも反映されます(Pt. 10 セクション10.1.6 参照)。

After working in several subcommittees, they worked very hard with members of the IRE (Institute of Radio Engineers), ASA (Acousitical Standards Association) and RMA (Radio Manufacturers Association), toward the standardization of disc recording. Such elaboration would later be reflected in the 1949 NAB Standards (see also: Pt. 10 Section 10.1.6).

実際、委員長の Hillard 氏はのちに、NAB標準規格委員会の「プロジェクトグループB(歪、S/N比、録音レベル)」と「プロジェクトグループF(周波数応答特性、ディスク再生装置とイコライザの組み合わせによる出力レベル、トラッキングエラー、針圧)」のメンバも務めました。

In fact, the chariman Mr. Hillard later became a member of the 1949 NAB Standards Project Group B (distortion; signal-to-noise ratio; recorded level) and Group F (frequency response characteristics and output level of disk reproducer and equalizer combination, tracking error and vertical force of disk reproducer).

また、RCA Victor の James (Jim) Bayless 氏が率いる小委員会は、業界内で統一されてなかった用語を整理し、用語集を編纂しました。これこそがのちに、1949年改定NAB規格策定時の小委員会(プロジェクトグループI)の行った作業(Pt. 10 セクション10.1.6 参照)の源流となるものです。実際、Bayless 氏はのちに、NAB標準規格委員会の「プロジェクトグループI(用語集、定義、記号)」のメンバも務めました。

Also, a sub-committee led by RCA Victor’s James (Jim) Bayless compiled glossary of terms and definitions, that was not yet standardized at that time. This is definitely the origin that later would be evolved into the work by 1949 NAB Standards Project I (see: Pt. 10 Section 10.1.6). As a matter of fact, Mr. Bayless later became a member of the 1949 NAB Standards Project I (glossary of terms and definitions; symbols).

The Hollywood Sapphire Group grew rapidly, with participation from all fields of recording. The dynamic mix of film sound and recording industry professionals provided fertile ground for discussion of common terminology and tools and standards of practice. The Hollywood Sapphire Group focused on technical matters, particularly the problem of standardization, more than did the New York group. By the second anniversary meeting in March 1948, the Hollywood Sapphire Group had expanded to fifty members, had formed a Re- cording Standards Committee and three subcommittees, and had drawn up a “Proposed List of Preferred Terms for Disc Recording.”

ハリウッド・サファイア・グループには、レコーディングに関するあらゆる分野から参加者が集い、急速な成長をとげた。映画音響のプロと録音業界のプロがダイナミックに交流することで、共通の用語やツール、エンジニアリング実践規範などについて議論する、肥沃な土壌を提供した。ハリウッド・サファイア・グループは、ニューヨーク・サファイア・グループよりも技術的な問題、特に標準化の問題に重点を置いていた。1948年3月の2周年記念会合までに、ハリウッド・サファイア・グループのメンバは50人にまで拡大し、録音標準規格委員会と3つの小委員会を設立、「ディスク録音における推奨用語集」を作成した。

“Chasing Sound: Technology, Culture, and the Art of Recording from Edison to the LP”, p.70, by Susan Scmidt Horning, The John Hopkins University Press, 201316.2.3 Gradual Disclosure of Trade Secrets

「サファイア・グループ」、特に「ハリウッド・サファイア・グループ」による交流・協力・標準化志向の姿勢は、当時標準化を目指すもうひとつの団体でも強く意識されていました。それが、Pt.8 や Pt.10 で追ってきた、NAB (National Association of Broadcasters, 全米放送事業者協会) の録音・再生規格委員会が行ってきた活動です。

The commitment by the Sapphire Group — in particular the Hollywood Sapphire Group — to interaction, cooperation and standardization, was also strongly recognized by another group that was also working toward standardization at the time. It was, of course, the National Association of Broadcasters (NAB) Recording and Reproducing Standards Committee since 1941, as we have already learned in the past parts (see: Pt.8 and Pt.10).

確かに、当初 NAB が対象としていたのは、ラジオ局用のトランスクリプション盤用の各種標準規格でした。しかし、1941年の時点ですでに「トランスクリプション盤の規格と市販のレコード盤の規格を、可能な限り相互に関連づける」という言及がありました(Pt. 8 セクション 8.1.5 参照)。1942年、ニューヨーク・サファイア・グループ設立のタイミングは、NAB 録音・再生規格委員会設立(1941年)〜初のNAB標準規格策定(1942)のタイミングと、見事に一致しているのです。

Indeed, the NAB initially targeted the standardization of electrical transcription discs for radio stations. However, as early as 1941, they already mentioned as: “an attempt will be made to correlate electrical transcriptions and phonograph record standards wherever possible” (see: Pt. 8 Section 8.1.5). The timing of the establishment of the New York Sapphire Group in 1942 concides perfectly with the establishment of the NAB Recording and Reproducing Standards Committee (1941) and the first publication of the NAB Standards (1942).

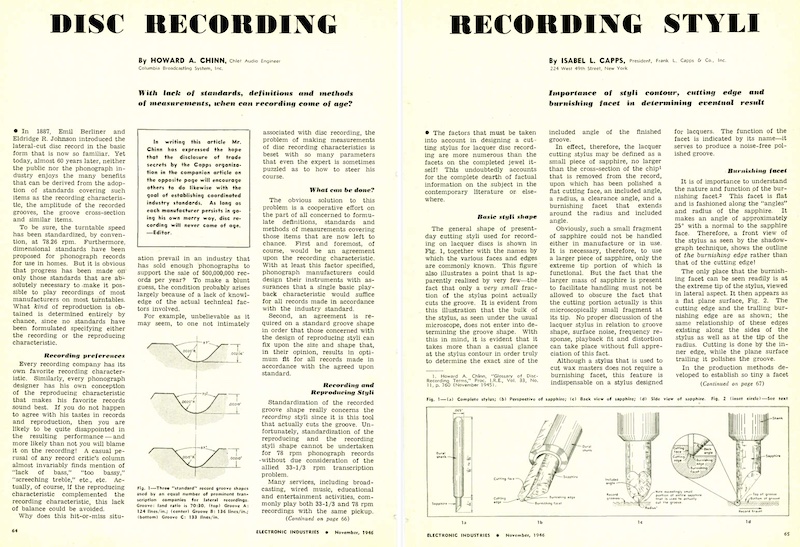

このような、企業の壁を超えた協力志向は、1946年発行の業界誌からも確認できます。Electronic Industries 誌の1946年11月号に掲載された、2つの記事です。

Such willingness to cooperate across company boundaries is also confirmed by two specific articles from a 1946 trade magazine “Electronic Industries”, in November 1946 issue.

1つ目は、CBS のチーフオーディオエンジニアの Howard A. Chinn 氏による記事「Disc Recording」です。Chinn 氏は、1942年および1949年のNAB規格策定時の執行委員会メンバです。

The first article is “Disc Recording”, authored by Howard A. Chinn, chief engineer at CBS. Mr. Chinn was also an executive committee member of the 1942 / 1949 NAB Standards Committee.

そしてもう1つは、Frank L. Capps and Co., Inc. の Isabel L. Capps 氏による記事「Recording Styli」です。さきほど紹介したように、録音カッター針の研究開発・販売で有名な Capps 社の2代目社長で、彼女もまた1949年NAB規格策定時のプロジェクトグループA (記録溝の形状、および再生針の形状) 小委員会のメンバでした。

The other article is “Recording Styli”, written by Isabel L. Capps of Frank L. Capps and Co., Inc. As I previously described far above, she was the second president of the Frank L. Capps and Co., Inc. She also was a member of the 1949 NAB Standards Project Group A (recorded groove shape; reproducer stylus contour).

この両者による、ディスク録音の記事とカッター針の記事が、見開きで並べて掲載されているのです。しかも驚くべきことに、この2記事は、ラジオ局用トランスクリプション盤に関する記事ではなく、当時は完全に秘密主義が徹底されていた、市販レコード盤の制作に関する記事なのです。

One article on disc recording, and the other on recording styli. These two articles appear side by side on the same page of the same issue. Also, more surprisingly, both articles were not for electrical transcription discs for radio industry, but for commercial (shellac) records (that traditionally secretive at the time).

source: “Disc Recording”, by Howard A. Chinn, Electronic Industries, November 1946, pp.64 & 66.

and “Recording Styli”, Isabel L. Capps, Electronic Industries, November 1946, pp.65,67,100,102,104,106,108 & 110.

この記事の囲み欄に、当誌編集長のコメントが記載されています。

The boxed comment from the editor declares the importance of these two articles.

In writing this article Mr. Chinn has expressed the hope that the disclosure of trade secrets by the Capps organization in the companion article on the opposite page will encourage others to do likewise with the goal of establishing coordinated industry standards. As long as each manufacturer persists in going his own merry way, disc recording will never come of age. — Editor.

Chinn 氏は(この「Disc Recording」という)記事を書くことで、そして隣のページに掲載された Capps 社の姉妹記事と並び、業界における企業秘密を公開することで、他社も同様に情報開示を行い、さらに協調的な業界標準を確立へと進むことを願っている。各メーカが独自の道を歩み続ける限り、ディスク録音の時代はやって来るはずもないのだ。 — 編集長。

(the comment in the adjoining box from the magazine's editor, for the article) “Disc Recording”, by Howard A. Chinn, Electronic Industries, November 1946, p.64Chinn 氏の記事は、ディスク録音時のラッカー盤/ワックス原盤に刻まれた断面形状が、各社ごとにバラバラであり、再生用針の標準的形状も決まっていないため、溝と針との接触位置にバラツキが生じている現状を簡潔に図解し、解説しています。

Mr. Chinn’s article briefly illustrates and explains the situation at that time in which the contact position between the groove and the needle varies because the cross-sectional shape engraed on the lacquer / wax masters at the time varied from company to company, and the standard shape of the reproducing needle had not yet been standardized.

一方 Capps 氏の記事では、バニシングファセット(Pt. 12 セクション 12.2.1 参照)を含めたカッター針の形状について図解し解説したのち、カットされた溝の断面形状のバリエーションについて細かく解説しています。

On the other hand, Ms. Capps’ article illustrates and explains the shape of the cutter stylus, including the burnishing facet (see also: Pt. 12 Section 12.2.1), followed by her detailed description of the variations in the cross-sectional shape of the resulting groove.

カッター針の形状や再生針のサイズ・形状すら標準化されておらず、録音再生EQカーブの標準化以前の問題であった当時の状況がよく分かると同時に、これらの技術的情報ですら、当時はほとんど公にされておらず、各社の現場エンジニアは秘密主義のもと独自の道を進んでいたのです。以下の Chinn 氏の記事の抜粋もそのような状況を説明しています。

The shape of cutter styli, as well as the size and shape of playback needles, was not yet standardized at the time — it surely was NOT just a problem of the lack of recording / reproducing characteristic standards. Even such technical information was hardly publicized at the time, and engineers in the field at each company followed heir own paths in secrecy. The following quote from Mr. Chinn’s article describes such deplorable situation.

As anyone who is familiar with the art knows, there is a dearth of published information concerning the groove shapes actually experienced in practice. Likewise, there is no material available covering the fine art of recording styli design and manufacture. For these reasons, the accompanying paper on “Recording Styli Design” not only sets a precedent, but also should prove of unusual interest to the recording engineer.

この(ディスク録音の)分野に詳しい人が知っている通り、現場での実経験に基づいた、溝形状に関する情報で公開されたものはほぼ存在していないのが現状である。同様に、録音用カッター針の設計と製造という精密工芸に関する資料も存在しない。このような理由から、姉妹記事である(Capps 氏の)「録音カッター針の設計」に関する論文は、(業界における)先例となるばかりではなく、録音エンジニアにとって非常に興味深いものである。

None of the data presented in the paper has ever been published heretofore. In fact, nowhere in the literature will one even find a detailed drawing showing the shape of a modern lacquer recording stylus. Curiously enough, even though this tiny tool is used by many, its real shape is a mystery to most. This comes about simply because the depth of focus of a microscope is so limited that only those portion of the stylus in a single plane are clearly visible for any given focus.

(Capps 氏の)論文で紹介されたデータは、過去に発表されておらず、今回が初の公開となるものである。現代のラッカー盤用録音カッター針(スタイラス)の形状を示す詳細な図面さえも存在していなかった。不思議なことに、この小さなツールは、多くのエンジニアに使われているにもかかわらず、その本当の姿は謎に包まれているのだ。それは、顕微鏡の焦点深度が非常に限定されており、どのような焦点でもスタイラスの各平面の一部分しかはっきりと見えないからである。

“Disc Recording”, by Howard A. Chinn, Electronic Industries, November 1946, p.66このように、各社の「企業秘密」ビジネスから、業界の技術者たちが協力しあいながら情報を共有し、同時に「標準規格化」を目指す流れが、徐々に進んでいきました。以前 Pt. 6 セクション 6.2 で紹介した、ハーバード大Cruft研の Frederik V. Hunt 氏のインタビューで語られた時代とは、ずいぶん変化が起こってきたというわけです。

Thus, in the mid-1940s to late 1940s, the trend in the industry gradually shifted from the “trade secret” business of each company to the “cooperate engineering” in which engineers in the industry cooperate with each other to share information and at the same time aim for “standardization”. This is quite a change from the era that was described in the interview with Frederick V. Hunt in the Cruft Institute at Harvard University (see: Pt. 6 Section 6.2).

そして、これらの取り組みは、1949年NAB標準規格に、「レコード溝の形状 (Record Groove Shape)」および「再生針の形状 (Reproducer Stylus Contour)」として規定され、1953年 NARTB および 1954年 RIAA にも引き継がれることになります。

After all, these efforts (including those by Mr. Chinn and Ms. Capps) would later be incorporated to the “Record Groove Shape” and “Reproducer Stylus Contour” sections in the 1949 NAB Standards, as well as 1953 NARTB and 1954 RIAA.

16.2.4 “Sapphire Group” to “Audio Engineering Society”

話を戻すと、ニューヨークとハリウッドでの「サファイア・グループ」、つまり、ディスク録音に従事するプロのエンジニア達が、企業の壁を乗り越えて連携しはじめたことにより、1947年の Audio Engineering 誌の創刊、そして1948年の Audio Engineering Society 設立につながったのです。同時に、サファイア・グループのメンバ、Audio Engineering 誌の執筆陣、Audio Engineering Society 設立メンバは、互いに重なりあっており、かつ、ラジオ局業界の NAB/NARTB 標準規格策定にも深く関わっていたのです。

Back to the “Sapphire Group” in NY and Hollywood — efforts by the groups, where professional engineers working on disc recordings began to openly collaborate together, overcoming corporate barriers, finally led to the first issue of Audio Engineering magazine in 1947, as well as the founding of the Audio Engineering Society in 1948. At the same time, the members of the Sapphire Group, the writers of Audio Engineering magazine, and the charter members of the Audio Engineering Society overlapped with each other, and were deeply involved in the development of NAB/NARTB Standards for the radio industry.

This corporate camaraderie worked and the Sapphire Group concept spread to another major recording center — Hollywood, California. The nucleus of a new communication network was established and maintained. It really served as the foundation stone for the AES. The Society emerged from those meetings of the Sapphire Group during the war years.

このような仲間意識の誕生により、(ニューヨークの)サファイア・クラブのコンセプトは、録音ビジネスの中心であるもう一ヶ所、カリフォルニア州ハリウッドにも広がっていった。そして、新しいコミュニケーション・ネットワークの核となるものができ、維持されるようになった。これが Audio Engineering Society の礎となったのである。つまり、戦時中のサファイア・グループの会合から生まれたのが、AES なのである。

“Reminiscences on the Founding and Development of the Society”, by Donald J. Plunkett, Journal of Audio Engineering Society, Vol. 46, No. 1/2, Jan./Feb. 1998, pp.5-6以下では、1947年の Audio Engineering 誌創刊当時までは、「オーディオ工学」(Audio Engineering)」という用語すら珍しいものだった、と書かれています。

The following quote from the Susan Schmidt Horning book notes that even the term “audio engineering” was quite rare until the first issue of Audio Engineering magazine in 1947.

The Sapphire Groups were founded by recording professionals—manufacturers of equipment and engineers affiliated with record companies, broadcasting stations, film sound studios, independent recording studios, and transcription services—but the field of audio encompassed all forms of sound engineering. By 1947, this included not only broadcasting and recording on disc, wire, and tape, but also public address, transmitter and receiver manufacturing, industrial sound, and acoustics. The term audio engineering was a relatively new one in the postwar period, so new that there was no publication devoted to it until 1947.

サファイア・グループは、レコード会社、ラジオ放送局、映画音楽スタジオ、独立系音楽スタジオ、トランスクリプション盤サービスなどに所属するプロの録音エンジニアやこれらの分野に従事する機器メーカによって設立された。しかし「オーディオ」という分野は、あらゆる音響工学を包含している。1947年までには、ディスク、ワイヤ、テープによる放送や録音のみならず、パブリックアドレス (PA)、送受信機製造、工業用音響、アコースティクス(音響学)なども含まれるようになった。「オーディオ工学」という用語は、戦後直後の当時においては比較的新しいものであり、1947年まで(オーディオ工学)専門の出版物がなかったほどである。

“Chasing Sound: Technology, Culture, and the Art of Recording from Edison to the LP”, p.71, by Susan Scmidt Horning, The John Hopkins University Press, 2013このように、戦時中から始まったサファイア・グループの民主的な活動、1947年の Audio Engineering 誌創刊、1948年の Audio Engineering Society 設立などを通じて、企業の壁を超えて、科学的に、アカデミックという公開の場で、「オーディオ工学」を議論し研究開発する雰囲気が醸成されていったのです。

In this way, through the democratic activities of the Sapphire Group which began during the WWII, followed by the publication of Audio Engineering magazine in 1947, then the establishment of the Audio Engineering Society in 1948, the atmosphere was fostered where “audio engineering” could be discussed, researched, and developed scientifically and in an open academic manner, beyond corporate boundaries.

本稿冒頭のセクション16.1.2 で触れた Audio Engineering 誌創刊号の編集長コラムにも、次のようなメッセージがみてとれます。

As we already saw at the beginning section 16.1.2 of this article, the first issue of the Audio Engineering magazine (May 1947) had the editor’s column, featuring the following paragraphs:

This branch of the industry is in sad need of standardization; different makes of records do not have the same cross-over frequencies, the degree of pre-emphasis at the higher frequencies varies, groove depth is not always the same, and there are still other factors which affect reproduction upon which no standards have been selected. Therefore, even the best reproducing equipment cannot give equally satisfactory results with all makes of records. By offering this magazine as a forum for the interchange of ideas, we hope to be able to contribute in some measure to eventual standardization of these varying techniques.

この(オーディオ工学という)業界は、標準化を切実に必要としている。レコード製造メーカによって、クロスオーバ周波数はまちまちであるし、高域プリエンファシスの度合いはバラバラで、さらに溝の深さも必ずしも同じではなく、その他のさまざまな要因が標準化されていない要因の全てが、再生時に影響を与える。従って、いかに最高の再生品質を誇る機器があったとしても、全てのレコードメーカの盤で等しく満足のいく再生結果を得ることができないのだ。意見交換の場として本誌を世に問うことで、このような様々な技術の標準化に少しでも貢献できれば幸いである。

“Transients: Introducing “Audio Engineering””, by John H. Potts, Audio Engineering, Vol. 31, No. 3, May 1947, p. 4.完全に秘密裏に開発され突然発表された Columbia LP は例外でしたが、戦後当時は NAB も ASA も RMA も、そして AES も、互いにメンバが重複しあっていたり、少なくとも連携しながら標準化に向けて動いていたのです。来るべき 1953年 NARTB = 1954年改定 AES = 1954年 RIAA 規格の策定もしかり。しかも、現場で腕を振るう各社の現役プロエンジニア達や録音部門責任者達みずからが、その任にあたっていたのです。

Whilst the Columbia LP was an exception, which was developed in complete secrecy and announced out of the blue in 1948, other postwar groups like NAB, ASA, RMA, AES were all woking toward the standardization with overlapping (or at least coordinated) memberships with each other. The same is true for the upcoming 1953 NARTB Standards = 1954 revised AES Playback Standards = 19544 RIAA Standards. Furthermore, professional engineers and the heads of the recording divisions of the companies were the ones in charge of these works.

ですから、各団体間で、互いの規格を批判し合うとか、反目し合うとか、そういった関係にはなかったことになります。

Therefore, it is understood that there was no mutual critisism between each other’s standards, or antagonism between associations and societies.

16.3 Toward the AES’s “Playback” Standards

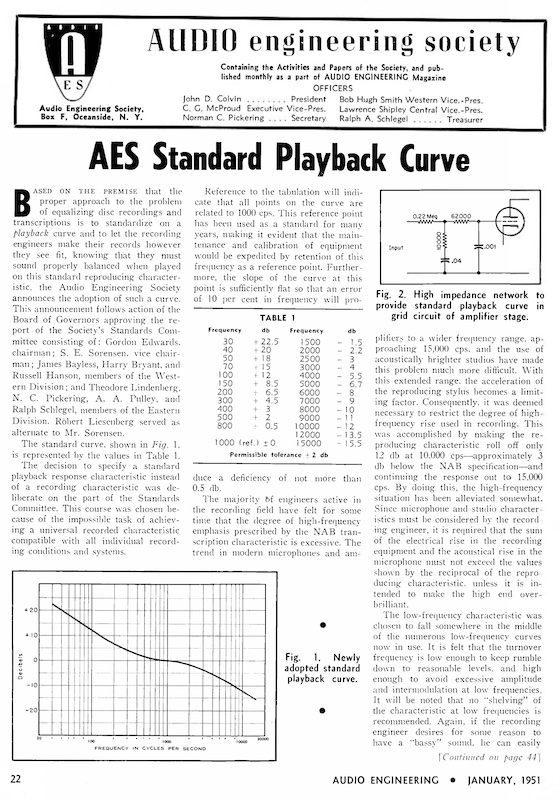

本Pt.15の最後は、1950年7月に策定され、1951年に正式発表された、AES標準規格委員会による「AES標準再生カーブ」の歴史についてみていきます。

Lastly, we are going to the detailed history of the “AES Standard Playback Curve”, developed in July 1950 and officially published in 1951.

そのAESカーブを見る前に、AES を生んだ雑誌と言える Audio Engineering の編集長コラム「Editor’s Report」の変遷をみながら、AESカーブが生まれていく過程を探っていくことにします。初代編集長 John H. Potts 氏 (創刊号〜1949年4月号、1949年3月16日に逝去)、2代目編集長 D.S. Potts(1949年5月号〜9月号)、3代目編集長 C.G. McProud(1949年10月号〜)により執筆されたとされるこれら毎号コラムは、当時のオーディオ工学に関わる多くの人々の意見の変遷を読み解けるダイジェストともいえます。同時に、同誌に協力していた当時の現役プロエンジニアの皆の共通認識が反映されたものでもあります。

Before the closer examination of the AES Curve itself, here is a look at the evolution of the “Editor’s Report” column, that appeared in each issue of Audio Engineering magazine. As we already know, this magazine gave birth to the Audio Engineering Society. These “Editor’s Report” column were written by the first editor-in-chief John H. Potts (until Apr. 1949, passed away on Mar. 16, 1949), the second editor-in-chief D.S. Potts (May 1949 to Sep. 1949), and the third editor-in-chief C.G. McProud (Oct. 1949 and beyond), and they reflects the evolution of the common recognition among people who were in charge of audio engineering at that time.

16.3.1 Nov. 1947: Editor’s Report: “More Record Data, Please”

録音再生カーブに関する最初期の編集長コラムは、LP登場前の1947年11月号に掲載されました。記録特性がバラバラな上に、ユーザに全く公開されていない、という状況を憂いています。

The first column on recording/reproducing curve was published in the Nov. 1947 issue, months before the advent of microgroove LPs. It complains the situation of inconsistent recording characteristics, also it being undisclosed.

すでに本稿 Pt. 9 セクション 9.2.2 で紹介済ですが、ここに再掲します。

I mentioned this column already in Pt. 9 Section 9.2.2, but here it is again:

source: Audio Engineering, November 1947, Vol.31, No.10, p.2.

NOW that better phonograph pickups and amplifiers are available, the need for more technal data on records is emphasized. To use this equipment intelligently, the cross-over frequency and amount of pre-emphasis used in recording should be known to the purchaser. If this is done, then both the manufacturer and user can be assured that the record is being reproduced as well as possible with the equipment used.

蓄音機のピックアップやアンプの性能が向上した現在、レコードに関する技術的なデータの必要性が今まで以上に重要になってきている。性能が向上した機器を有効活用するには、ディスク録音において使われるクロスオーバー周波数とプリエンファシスの値が、レコードの購入者に伝えられる必要がある。そうすれば、機器製造者も、レコード再生を行うユーザも、そのレコードが可能な限り良好に再生できている、と確信できるようになるからだ。

It is not enough simply to provide the operator with controls sufficiently flexible to accommodate all recording characteristics and to rely on his judgment to select the proper reproducing characteristics.

ありとあらゆる録音特性に対応できるように、再生機器側に柔軟なコントロールを装備し、あとはリスナー自身に正しい再生カーブを判断させる、という単純な対応では十分とは言えないのだ。

After all, there may be a group listening, each member of which has different hearing characteristics, so that the operator’s idea of what constitutes good reproduction may not coincide with that of others with better hearing. Children, especially, usually have keen hearing and it is important that they get good reproduction if they are to cultivate a taste for the best.

というのも、人はそれぞれ聴力に差があるもので、集団でリスニングを行う場合、再生機器のオペレータが考える「良い再生」と、聴力に優れた人の考える「良い音」とが一致しない場合があるからだ。特に子どもは非常に鋭く優れた聴力を備えているものであり、良い音楽・良い音への感性を養うためには、良い再生音で聴かせることが重要である。

MORE RECORD DATA, PLEASE, John H. Potts, Audio Engineering, Vol.31, No.10, November 1947, p.2つまり、Potts 氏のこの文章は、「単に再生機器側でいかなるカーブにも対応可能にするだけでは不十分」、そして「レコード製造側が、どのような特性・カーブで記録したかをしっかり公にする必要がある」という主張です。同時にこれは、電気録音黎明期からLP登場後に至るまで、ずっと果たされなかった大問題でもあります。

So, Mr. Potts stresses in this article like: “it is not sufficient that reproducing equipments having a variable EQ setting feature”, and “record manufacturers should make public the detail of the recording characteristic (curve) used for every record”. Also at the same time, this huge problem has continued to exist since the early years – even after the advent of microgroove LP records.

そして、「市場に様々な記録特性が乱立する(しかも詳細が公開されていない)現状を改め、業界で標準規格を策定する」ことが、本質的な解決策になる、ということでもあります。

Also, it easily leads that the fundamental solution would be the standardization of recording/reproducing characteristic, correcting the situation of various characteristics being around (and technical details being kept confidential).

16.3.2 Aug. 1949: Editor’s Report: “More Standardization”

Audio Engineering 誌には他にも、「High Fidelity」という用語に関するコラム(1947年5月号、1947年10月号、1948年2月号など)、「ワイドレンジ再生」のコラム(1948年5月号)、革命的と言われた(そしていまのコンピュータ実装の礎になった)発表直後のトランジスタに関するコラム(1948年8月号)、AES 学会設立に関するコラム(多数)などが掲載されます。

In later issues, Audio Engineering magazine featured such editor’s reports as on “High Fidelity” (May 1947, Oct. 1947, Feb. 1948, etc.); “Wide Range Reproduction” (May 1948); on new technology of Transistor (that soon changed the world entirely as computers) and its application for amplification (Aug, 1948); on Audio Engineering Society (in many issues).

「標準化」という側面では、1949年6月号および7月号の「トランスのインピーダンス標準化」に関するコラムが熱く語られています。それらを引き継ぐ形で、1949年8月号に「もっと標準化を」というコラムが掲載されます。ディスク録音・再生カーブの標準化とは関係ない話ですが、みてみましょう。

In the context of “standardization”, June and July 1949 issue of Editor’s Report argued passionately on “Transformer Impedance Standardization”. Then another column followed in August 1949 issue, entitled “More Standardization”, although it is not directly related to the standardization of disc recording and reproduction.

source: “Editor’s Report: More Standardization”, Audio Engineering, Vol. 33, No. 8, August 1949, p. 6.

Following our discussion of this subject in the two preceding issues, we are reminded of the activities of several standardization groups who have done commendable work in direction over the past years. These standards have covered practically all broadcast amplifier equipment, and microphones have been standardize just recently.

前々号および前号で「標準化」というテーマをとりあげてきたが、いくつかの標準化団体がここ数年間方向性を明確にして賞賛に値する活動を行っていることに気付かされる。これらの規格は実質的に全ての放送用アンプ機器をカバーしており、マイクロフォン(のインピーダンス)はつい最近標準規格化されたばかりである。

Most engineers in audio work with broadcast and recording organizations know these standards, and have been working with them since their adoption. But the importance of any standard — regardless of by whom promulgated — lies not in its acceptance by a few, but rather by its universal aceptance. The independent engineer who designs and installs a high-quality public address system far from any broadcast center must know adn adhere to these standards if they are to be of the greatest benefit. Even the individual who constructs for himself — as a hobby — a home reproducing system which is equivalent in performance to a broadcast station should also have acess to and should follow the standards.

放送局やレコード会社で仕事をしているエンジニアの大半は、これらの規格を知っており、標準規格採用後はこの規格に則り仕事をしてきている。しかし、規格策定・公布元がどこであろうが、標準規格の重要性というのは、一部の人に受け入れられるのではなく、普遍的に受け入れられることにある。放送センターから遠く離れたところで高品質の放送設備(パブリックアドレスシステム)を設計・設置する独立エンジニアも、これら標準規格を知り、遵守しなければならない。また、放送局と同等の性能の家庭用再生システムを「趣味で」持つ個人も、この標準規格にアクセスし、それに従わなければならない。

To this end it is desirable that the standards be given the widest possible distribution, and they be made available to anyone who wishes them. If for no other reasons, the saving in cost to manufacturer, jobber, and user should be appreciable because of the reduction of the number of types of equipment required to cover the needs.

この目的のためには、標準規格は可能な限り広く配布され、希望する者が誰でも利用可能にすることが望ましい。何か理由があるのでない限り、機器製造業者、流通業者、利用者にとって、ニーズを満たすために必要な機器の種類を減らすことができるので、コスト削減になるはずである。

The fact that the standards exist should certainly reflect credit to those who have been charged with the many hours of committee work, the interminable letter writing, and the inevitable discussions which arise when differing opinions must be adjusted to come out with one specific set of standards. Standards are not plucked, ready-made, from the sky — they represent years of experience and a keen analysis by component engineers.

標準規格が存在する、という事実は、その裏に間違いなく、長時間に及ぶ委員会活動、延々と続く手紙や書類のやりとり、異なる意見を調整して1つの企画を作り上げるために避けられない「議論」、これらを行ってきた方々の功績がある、ということだ。標準規格とは、完成形が天から降ってきたのではなく、エンジニアの皆さんの長年の経験と鋭い分析から生み出されたものなのである。

MORE STANDARDIZATION, D.S. Potts or C.G. McProud, Audio Engineering, Vol.33, No.8, August 1949, p.6この最後のパラグラフには、非常に重みがあります。コンピュータの世界における IETF (Internet Engineering Task Force) の出す RFC (Request For Comments) 文書と同様、放送技術、機器技術、録音再生技術など、さまざまな工学的製品の世界には標準規格がありますが、これらは一朝一夕で定められたものではなく、多くの専門家たちの長時間にわたる議論と折衝の末に生まれたものなのです。

The last paragraph meant (and has meant) a lot to us. Just like the RFC (Request For Comments) by the IETF (Internet Engineering Task Force), which has been fundamental in the internet technology and computer engineering field, standardization in the radio/TV/audio industries (in broadcasting, equipments, recording/reproducing technology) is inevitable and important. Also, these standardization was established in a day — but a result of long discussion on the controversial topics before the negotiations were made among professional engineers and researchers.

16.3.3 Jun. 1950: Editor’s Report: “Recording Characteristics”

1950年4月号で、再び「標準化について」という編集長コラムが掲載されていますが、この時はプロの現場で導入著しいテープの標準化に関する話でした。

Apr. 1950 issue of the Audio Engineering magazine also features the Editor’s Report colum on the standardization, this time for the magnetic tapes, which had been gradually popular in the professional field.

次にディスク録音・再生カーブ標準化に関連する編集長コラムが掲載されたのは、1950年6月号でした。ここで、来たる「AESカーブ」の考え方に連なる意見が述べられています。

Next column on the disc recording/reproducing standardization was published in the June 1950 issue. It apparently describes the basic idea of what would become the “AES Standard Playback Curve”.

そしてこのコラムは、「XXレーベルのYYというレコードのターンオーバーとロールオフを教えてください」「現在入手可能な全レーベルの全EQカーブ一覧を教えてください」といった手紙が、編集部にひっきりなしに届いていたであろうことも示しています。

This particular column also shows that the Editorial had kept receiving letters, asking: “what is the correct turnover / rolloff value for the record YY from the XX label?” or “please provide the complete list of the playback EQ curves for all the records ever released”.

source: “Editor’s Report”, Audio Engineering, Vol. 34, No. 6, June 1950, p. 4.

Many of the more enthusiastic audio hobbyists — always on the search for perfection in their record reproduction systems — search in vain for completely reliable information about the recording characteristics employed in the making the various brands of phonograph records. Their letters indicate considerable interest, but in most instances they are completely unanswerable.

完璧なレコード再生システムを探求する熱心なオーディオ趣味人の多くが、レコードの各製造会社(レーベル)ごとに採用されている録音特性について、完全に正しく信頼性の高い情報を求めて探索を行い、そして最後は失敗に終わる。(我々の元に届く)このような手紙は、かなり興味をひくものであるが、ほとんどの場合、回答が不可能なものばかりである。

This is not altogether the result of our lack of knowledge of what goes on in the recording industry, and it would most certainly be easier to provide each inquirer with a simple printed slip showing the recording characteristic employed by each of the many companies in the field. But, for a number of reasons, this information is not available. In the first place, the characteristics used by a given manufacturer may be changed from time to time, depending upon the opinon of the engineer-in-charge or of those responsible for the over-all sound quality of the product. It also depends upon microphone placement, the studio, or the arrangement of the orchestra in the studio. WIth any given electrical characteristic, a great variety of “recording characteristic” can be obtained simply by moving the musicians around, or by moving the acoustic “flats”, or even by allowing the temperature in the recording studio to rise by as little as ten degrees.

これは、我々(本誌編集陣)が、録音業界のことを知らないから、というわけではない。確かに、録音業界における会社(レーベル)が採用している各録音特性を一覧できる簡易の印刷物を、問い合わせをしてきた人に提供することは簡単かもしれない。しかし、さまざまな理由から、これらの情報の入手は容易ではない。そもそも、あるメーカ(レーベル)が採用している特性は、担当エンジニアや音質全般の責任者により、その時々で変更されることもある。また、マイクの設置位置、スタジオそのもの、オーケストラの配置などにも左右される。電気的な録音特性がなんであろうとも、演奏者を移動したり音響反射板を移動したり、はたまた録音スタジオの温度を10度あげたりするだけで、実にさまざまな「録音特性」を得られることになる。

What, then, is the solution for the amplifier builder who wishes to have one switch labeled RCA, Col, ffrr, LP, and so on, which may be set for any given record with the assurance that it will be played back with optimum quality? It is possible to build such a device which will be infalliable? Can the user read the label, set the controls, and just sit back and enjoy his music?

では、RCA / Col / ffrr / LP などと書かれたスイッチを1つ用意し、どのレコードにも最適な音質で再生できるようにしたい、と考えるアンプメーカにとっての解決策とは何であろうか。このような(いかなるレコードにも対応可能な)完璧な装置を作ることは可能なのであろうか?アンプ利用者(リスナー)はただレーベルを読み取り、補正コントロールを設定し、あとはどっしり座って音楽を楽しむだけ、なんてことは可能なのだろうか?

There is a solution to this problem, but it does not come in the form of an answer to the questions proposed. The logical solution, in our opinion, is to provide an amplifier with sufficient flexibility of control that any type of recording characteristic in use can be accomodated readily. Then, the listener can put on the record and adjust the controls so that it sounds best to him. In the final analysis, this is what he is trying to achieve, but the approach should be based on the ear’s satisfaction and not upon the shape of the response curve.

この問題にはひとつ解決策がある。しかしそれは提案された質問に対する答えという形ではない。論理的な解決策とは、どのような録音特性にも対応できるような、柔軟なコントロールが可能なアンプを用意することである、そう私たちは考えている。そして、リスナーはレコードを聴きながら、それが自分にとって最も良い音になるようにコントロールを調整できる。しかし、そのアプローチは、応答曲線の形状に基づくのではなく、耳の満足度に基づくべきものである。

The practical method of doing this — without the necessity of determing the adjustments each time a record is played — is to set up the equalizing controls on a series of tap switches, with the various positions numbered. Then each record can be coded with a set of numbers chosen for best reproduction, and when each is played, settings can be repeated.

これを(レコードを再生する度に微調整を行う必要なしに)行う現実的な方法とは、再生用イコライジングコントロールを一連のタップスイッチのようにしておき、さまざまなポジションにあわせて番号が振られているようにする。そして、それぞれのレコードに、ベストと思われるスイッチ番号を割り当て、レコードを再生する度にその番号を選ぶようにすれば、同じポジションが再現できることになる。

Thus it is hoped that a number of inquires can be answered at once with a method which can eliminate the need for knowing the presumed recording characteristic.

このようにすれば、(ここのレコードの)推定録音特性そのものを知らずとも、(自分が「いい」と思った設定を番号に割り当てておけば、自分の耳にとってベストな)設定を行えることになるし、(本誌に寄せられる)個別の質問にいちどに答えられることになる、と期待される。

In all fairness to certain manufacturers — notably Columbia and London ffrr — it should be stated that many characteristics are adhered to quite closely as far as the electrical equalization is concerned. But this does not guarantee that any given record will sound best when playd back with the complement of the stated characteristic, and the personal selection by the user of the desired playback curve is certain to be more satisfactory in the long run. In spite of all this, though, it does seem as though record manufacturers would contribute more to standardization if they did publish their characteristic.

一部の製造メーカ(レーベル)、特に Columbia や London ffrr など、に公平を期すべく、電気的なイコライジングという点に関しては、多くの特性はかなり忠実に守られている、と述べておく。しかし、だからといって、ある特性で録音されているとされる盤を、その補完特性で再生した時に、必ず最良の音になる保証はないわけであり、ユーザが個人的に好みの再生カーブを選択した方が、長期的な観点からは満足いくものになることは間違いない。しかしそれにしても、レコード製造会社(レーベル)がそれぞれの特性を公表しさえすれば、より標準化に貢献できていたであろうに。

Maybe it would be possible for all record manufacturers to use a “standard reproducing system” for their monitoring and checking. If the original recording were then made to sound right on the standard system, it seems certain that the ultimate listener would be assured of hearing the music as the producer intended it to be heard — provided his home system were closely similar to the standard. At least, he would have some place to start.

全てのレコード製造メーカ(レーベル)が「標準的な再生システム」を使ってモニタやチェックをすることが可能かもしれない。そのような標準再生システムでオリジナル録音のレコードを正しく鳴らすことができれば、最終的なリスナーは、自宅のシステムがその標準システムに近いものであれば、製作者が意図した通りに音楽を再生できている、と確信できるであろう。少なくとも(微調整を行う前の)スタート地点が明確にされるのである。

RECORDING CHARACTERISTICS, C.G. McProud, Audio Engineering, Vol.34, No.6, June 1950, p.4特に、最後から2番目のパラグラフに書かれていることは非常に重要で、当時は (1) 自社の録音・マスタリング(カッティング)スタジオを持っていた大手レーベルでは、録音EQカーブはかなり厳格に管理され、全スタジオで共通の設定が使用されていた、 (2) 独立系スタジオでは、スタジオごと、ときには時期ごとに録音EQカーブにばらつきがあった、つまり (3) 特にマイナーレーベルは、録音セッションごとに使用したスタジオごとに、録音特性にばらつきがあった可能性が高い、ということの傍証となります。

In particular, what is written in the second paragraph from the last is very important, because it shows some collateral evidence of: (1) major labels that had their own recording / mastering (cutting) studios controlled their recording EQ curves quite strictly, and used the same settings for all studios; (2) independent studios had variation in recording EQ curves from one studio to another, and from one period to another; and (3) minor labels in particular, used several studios, so the recording characteristics might differ from studio to studio for each recording session.

本稿で何度となく登場している(多くのことを私に教えてくれた)達人エンジニア・録音技術史研究者 Nicholas Bergh さんも現物を所有しているという、RCA Victor 社内の社外秘技術ドキュメント(1940年2月発行、380ページオーバー、全15セットしか存在せず全てシリアル番号が振られて厳格に管理されていた)を仔細に読み解く機会に恵まれましたが、この中でも、世界中の RCA Victor 管轄のスタジオにおける録音特性は非常に厳格に統一管理されていたことが確認できました。

I had a privilege to read all the way through the confidential technical document of RCA Victor (published in February 1940; over 380 pages; only 15 sets made; each copy with serial number and strictly managed). Mr. Nicholas Bergh, a master engineer and a astonishing historian of recording technology, also owns an actual copy of it. Anyway, I could confirm that RCA Victor had controlled and maintained its in-house recording characteristics throughout its all studios all around the world. So at least major labels had/has adhered to their own recording EQ characteristics quite strictly.

つまり、少なくともメジャーレーベルにおいては、個々のスタジオのマスタリング (カッティング) エンジニアがその時の気分や個人的嗜好で、勝手に録音特性をいじったりすることはなかったのです。

In other words, no mastering (cutting) engineer of major labels could alter the recording characteristics according to his/her moods or his/her preferences.

16.3.4 Jul. 1950: Editor’s Report: “Playback Standards”

翌月号の編集長コラムでは更に踏み込んで、「標準録音カーブ」の代わりに「標準再生カーブ」を採用すべきである、という意見が解説されます。これは、編集長ひとりの私見というよりは、Audio Engineering 誌の執筆陣、つまり Audio Engineering Society の創設メンバや会員、すなわち、当時の録音/マスタリング現場で活躍するプロのエンジニアの多くの意見を反映したものである、と考えられます。

The Editor’s Report column in the following month’s issue goes even further, expressing his opinion about “Standard Playback Curve” in place of “Standard Recording Curve”. Apparently, this opinion is not only his own, but the consensus of all the authors in Audio Engineering magazine, thus charter members of the Audio Engineering Society, and many professional engineers who were working at the recording / mastering studios at that time.

その本質は「録音カーブを標準化するよりも、再生カーブを標準化して、マスタリング(カッティング)する側が、その再生カーブで適切に聴けるようにする方が実現が楽であるし、ユーザ(リスナー)の負荷も軽減される」「レコード製造側は、こだわりの録音カーブを使い続けることで、またはイコライジングを施すことで、独自の音作りを行える余地が残せる」「同時に、ユーザは一種類の再生カーブで間違いなくあっている、という安心感が得られる」といったあたりでしょう。

The essence of this comment would be: “it is easier to standardize playback curves than to standardize recording curves”; “it is easier for the mastering (cutting) company to use the standardized playback curve for quality check, which will enable to reduce the burden of the users (listeners)”; “the record manufacturers still can continue to use their particular recording curves and leave room for their own sound creation through equalization”; “at the same time, users can feel secure that one type of playback curve is definitely the right one.”

source: “Editor’s Report”, Audio Engineering, Vol. 34, No. 7, July 1950, p. 4.

The wide variety of recording characteristics which are in common use among record manufacturers is undoubtedly the result of a difference of opinion among those responsible for the curves selected. If one manufacturer believes that his product will have a slight selling “edge” over another’s by virtue of the recording curve which he elects to use, he is by all means entitled to use that curve. Similarly, where else can the manufacturer of radio-phonograph combinations vary his product from another’s except in tone quality or cabinet design?

各レコードレーベルの間で使用されている多種多様な記録特性は、間違いなく、それぞれの録音カーブを選択した責任者間の意見の相違が生んだものである。もしもあるレーベルが、自ら選んだ録音カーブによって、他社よりも少しでも「販売上の強み」を持つと考えるのであれば、そのカーブを採用する権利があると言える。同様に、ラジオ電蓄製造業者が、他社の製品と差別化するには、キャビネットデザインとトーンコントロール部分以外に変えるところはないわけであろう。

It is conceivable, however, that one record manufacturer may elect to decrease the high-frequency response of his product in order to give that “mellow” sound. The set manufacturer adjusts his reproduction so that this particular product sounds right to him — which could easily result in a unit which had a predominance of highs. Records of another manufacturer might then sound shrill or screechy, depending on the recording curve employed. The result of this arrangement is certain to be a hodge-podge.

しかし、次のように考えられないだろうか。あるレコードレーベルが「まろやかな」「メローな」音を志向して、高域周波数応答を下げた録音カーブを選択することはあり得る。そして、再生機器製造メーカ側は、そのレコードにあわせて、「正しい」と思える音に(トーンコントロールを)調整する。その結果、高域が強調されすぎた音になりがちである。この設定のまま、他のレーベルのレコードを再生すると、録音カーブによって、音が小さくなったり、金切り声になったりする。結果、レーベルとカーブ設定の組み合わせがゴチャゴチャになってしまうのは目に見えている。

Actually, this is what has been happening for years. Only within certain limits have manufacturers standardized on a recording characteristic — each one, possibly, has adhered to his own standards, but not all to the same ones.

まさに、このようなことが長年起こっていたのである。録音特性は、あるレコード製造メーカ(レーベル)が、ある一定の範囲内で標準化したものである。各レーベルはおそらく、それぞれ独自の標準規格を定めそれに従ってきたわけだが、(たとえ同一レーベルのレコードであっても)全ての盤が同一録音特性に従っているわけではない。

“Editor's Report: Playback Standards”, by C.G. McProud, Audio Engineering, Vol. 34, No. 7, July 1950, p.4そして、実はこの編集長コラムが、AES の標準規格委員会によって提案され、翌年正式採用される「標準再生カーブ」のことを指していることが語られます。

And the following paragraphs of this Editor’s Note would reveal that the Standards Committee of the Audio Engineering Society had already submitted a proposal, which later would become the AES Standard Playback Curve next year.

The Standards Committee of the Audio Engineering Society has submitted a proposal which has more merit, although in some particulars it is revolutionary. Let each record manufacturer choose what recording curve he considers optimum, but let him make that selection by listening to his product with a Standard Playback Curve. This does not mean that he is governed by any standards whatsoever — that is, he is free to accentuate bass or treble as much as he wishes. The only limitation is the system used for playback.

AESの標準規格委員会は、よりメリットの大きい提案を提出した(革命的な箇所もあるとは言えるが)。各レコード製造メーカ(レーベル)は、それぞれが最適と思われる録音カーブを選択してもらうが、その選択は、自ら製作したレコードを標準再生カーブで試聴した結果で行うこととする。これは、録音時になんらかの標準規格に縛られることを意味していない、つまり、低域や高域を強調するのは各社の自由である。唯一の制限は、再生(試聴)に使うシステムである。

The adoption of a standard playback system would not limit either record manufacturer or set designer. Either could make his product as “bassy” or as “toppy” as he wished. But the set manufacturer with the bassy set would know that bassy records would sound awful on his product; the record manufacturer with bassy records would know that his product would sound on a bassy set.

この標準再生システムを採用すれば、レコードレーベル側も再生機器開発業者側も制約をうけることはない。レーベル側も、再生機器メーカ側も、自社製品を好きなだけ「低域ブンブン」にしたり「高域キンキン」にしたりできる。しかし、低域ブンブンな再生セットを製造したメーカは、自社再生セットでは低域ブンブンなレコードはひどい音で再生されると認識することになる。そして低域ブンブンなレコードを製造したレーベルは、自社のレコードが低域ブンブンな再生セットではひどい音で再生されると知ることとなる。

What would be the final result? Both sets and records would shortly arrive at a reproduction which was very close to the proposed curve, to the benefit of all. The user of custom equipment — like most of AE’s readers—- would know the standard curve was the one used by the record manufacturer in planning his product, and could safely settle on this curve for his own equipment, making such minor changes as might suit his own ear.

では最終的にはどうなるのであろうか。再生セット側もレコードレーベル側も、提案されたカーブに非常に近い再生音に遠からず到達することになり、全ての人にとって有益なものとなるであろう。本誌の読者の大半がそうであろうが、カスタム機器(オーディオコンポーネント)利用ユーザは、レコードレーベルが製品規格時に使用した各社の録音カーブを知っているので、安心してそのカーブに合わせ、さらに自分の耳に合うように微調整を加えていける。

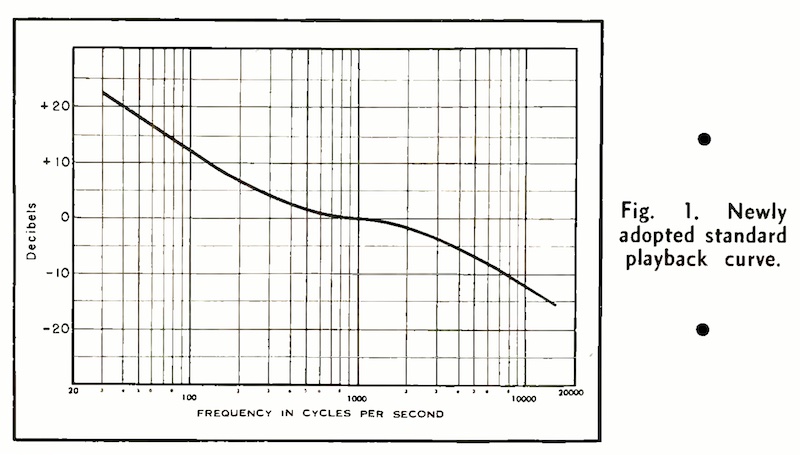

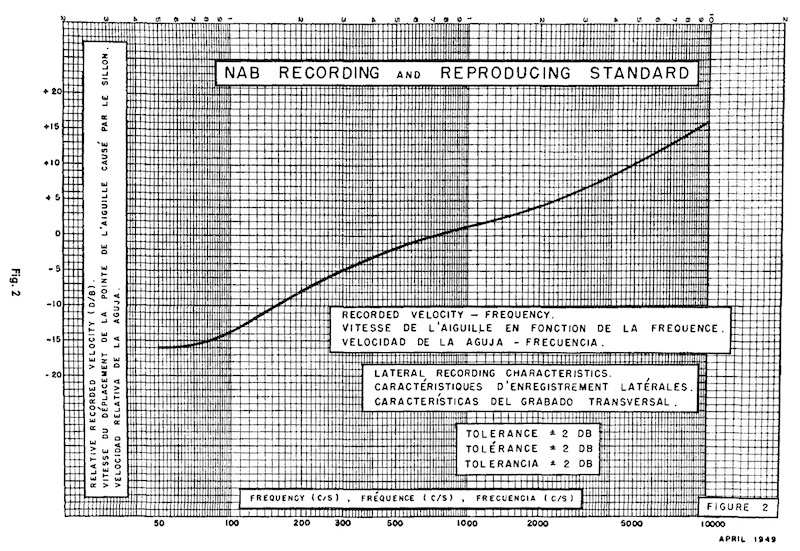

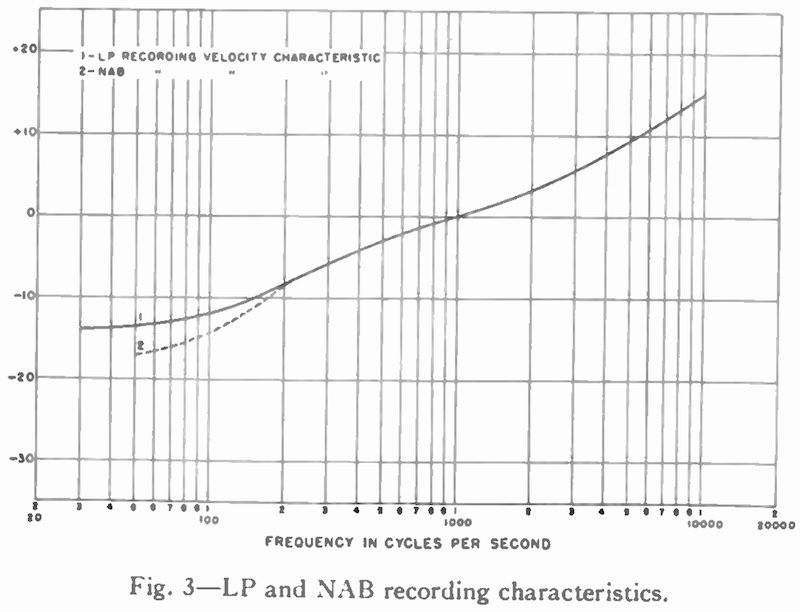

Technically, the proposed curve is symmetrical around 1000 cps, with low- and high-frequency turnover frequencies of 400 and 2500 cps respectively. This curve requires a 6-db per octave boost at the low end, with the 400-cps turnover frequency. The roll-off is also 6 db per octave, being down 12 db at 10,000 cps. This is somewhat less than the present NAB standard which requires a 16-db roll-off at 10,000 cps, but there is considerable evidence that the latter is too great. The FCC standard of 75 microsecond delay, selected for FM broadcasting, is in the direction of less pre-emphasis than that used in NAB transcriptions, and is cited as the principal authority for the desired change. The AES proposal is based on a delay of 63 microseconds.

技術的な話をすると、今回提唱されたカーブは、1000Hz を中心に対称となっており、低域ターンオーバー周波数は400Hz、高域ターンオーバー周波数は2,500Hzとなっている。低域では400Hzターンオーバーで、6dB/オクターブのブーストとなる。ロールオフも6dB/オクターブであり、10,000Hz で -12dB となる。このロールオフは、現在のNAB標準で採用されている -16dB (at 10,000Hz) よりいくぶん弱いが、後者(NAB 録音カーブの +16dB at 10,000Hz、という高域プリエンファシス)はあまりに強すぎる、という無視できない証拠がある。現在FM放送で採用されている 75μsという FCC (米国連邦通信委員会)の基準は、NAB トランスクリプションで使用されているものよりプリエンファシスが少なく、この FCC 75μs という時定数は、望ましいとされる変化の主たる根拠となっている。ちなみに AES の提唱する(再生)カーブは、時定数 63μsをベースとしている。

It is believed that this standardization of the playback system would do more toward standardization of over-all record characteristics than any attempt toward securing a voluntary cooperation with standards for recordings.

このような再生システムの標準化により、録音カーブ側に標準規格を定め(レーベル側、録音エンジニア側に)自主的な協力を確実なものにする、という試みよりも、全体的なレコードの特性標準化にもっと役立つ、と考えられているのである。

“Editor's Report: Playback Standards”, by C.G. McProud, Audio Engineering, Vol. 34, No. 7, July 1950, p.416.3.5 Jan. 1951: Editor’s Report: “Recording Characteristics”

そして、Audio Engineering 1951年1月号(のAES学会誌セクション)にて、AES Standard Playback Curve が初めて公になりましたが、その号の編集長コラムは、いままで議論されてきた内容のまとめでもあり、業界内をあげてのディスク録音再生特性の標準化を強く望む内容となっています。

Then the “Journal of the Audio Engineering Society” section of the January 1951 issue of the Audio Engineering magazine, “AES Standard Playback CUrve” was finally published. The Editor’s Report column in the issue was a summary of the past columns and discussions, expressing the strong desire for industry-wide standardization of disc recording and playback characteristics.

source: “Editor’s Report”, Audio Engineering, Vol. 35, No. 1, January 1951, p. 10.

Standardization of recording characteristics is a subject with which this column has been concerned for some time — principally because the record manufacturers collectively have done little or nothing to settle the problem. The original LP curve adopted by Columbia at the introduction of the long-playing record has apparently been followed quite closely by Columbia, but not all LP manufacturers have used the same curve consistently. This variation has made it mandatory that manufacturers of amplifiers provide adequate equalization facilities to accommodate all of the existing characteristics, and individual constructors have encountered some troubles in trying to secure optimum response for all makes of records.

録音特性の標準化は、本編集コラムでも以前から関心を寄せてきたテーマである。その主たる理由は、今に至るまで、この問題を解決するべくレコードレーベルが一丸となっておこなったことが、ほとんど何もないからである。Columbia レーベルは、(1949年の)長時間レコード登場時に Columbia 自身が採用した、オリジナルのLPカーブをほぼ忠実に守り続けているが、LP をリリースしている全てのレーベルが同じカーブを一貫して使ってきたわけではない。このようなばらつきがあるため、アンプ製造メーカが既存の全ての特性に十分対応可能なイコライザを用意することが義務のようになっている。しかし個々のアンプメーカは、全レーベルのレコードに対して最適なレスポンスを得られるようイコライザを設計しようとしても、トラブルに直面することがある。

The Standard Playback Curve recently adopted by the Audio Engineering Society could solve this problem completely for the future. Unfortunately, many hundreds of record titles have already been released with various high-frequency pre-emphasis characteristics and nothing can be done about them, but in the years to come there will be many more thousands of record titles made. A change should be made some time, and the sooner the better.

AES が最近採用した「標準再生カーブ」は、将来的にこの問題を完全に解決する可能性がある。残念ながら、すでに何百というタイトルのレコードがさまざまな高域プリエンファシス特性で販売されており、それらに対してはどうすることもできないが、これから先、さらに何千もの新譜が作られるわけなのだ。変化はいつか必ず起こさなければならず、そして早ければ早いほど良いわけである。

The idea of standardizing the playback curve rather than the recording curve is based on the general need for standardization of monitoring facilities in recording studios and elsewhere. If every manufacturer were to judge record quality and equalization under listening conditions as nearly as possible identical, the resulting product would then reflect only the individual preferences of musical directors. These differences are normal, and would be expected even if all companies made their records on the same equipment. However, there would not be any variation in the records technically, and all would reproduce with the same equalization. Changes made by the listener to suit his own preferences would be equally effective on all records, and the need for constant shifting of turnover frequency or the amount of roll-off would be eliminated entirely.

録音カーブの標準化ではなく、再生カーブを標準化する、というアイデアは、録音スタジオ等におけるモニタ設備の標準化、という一般的な必要性に基づいている。もしも、各レーベルがレコードの品質やイコライジングを、可能な限り同じリスニング条件で判断した場合、出来上がる作品(レコードに記録された音源)には個々の音楽監督の好みが反映されることになる。各社が同じ機材でレコードを製作したとしても、このような違いが生じるのは当然のことである。しかし、個々のレコードの技術的な差はないと言えるし、全ての盤を同じイコライジングカーブで再生させることになる。リスナーが自分の好みに合わせて(トーンコントロールなどを)変更すれば、それは全てのレコードに対して同様の効果をもたらすし、ターンオーバー周波数やロールオフ量をつねに変更する必要がまったくなくなるのである。

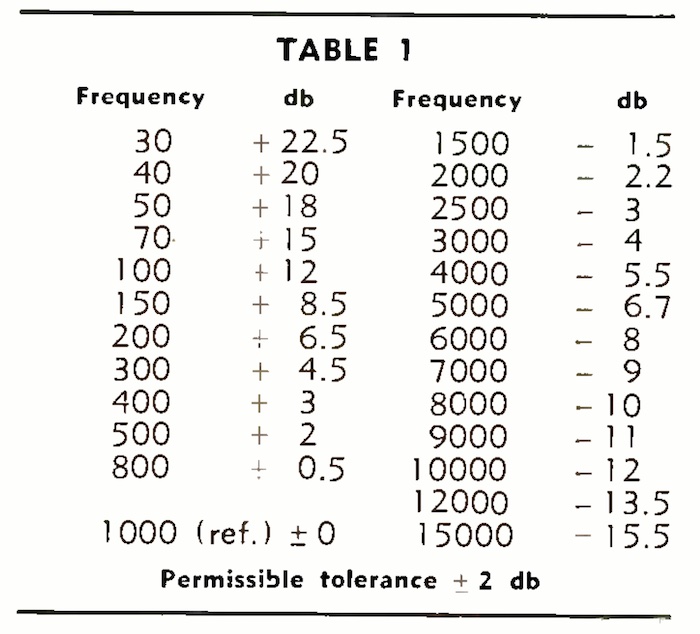

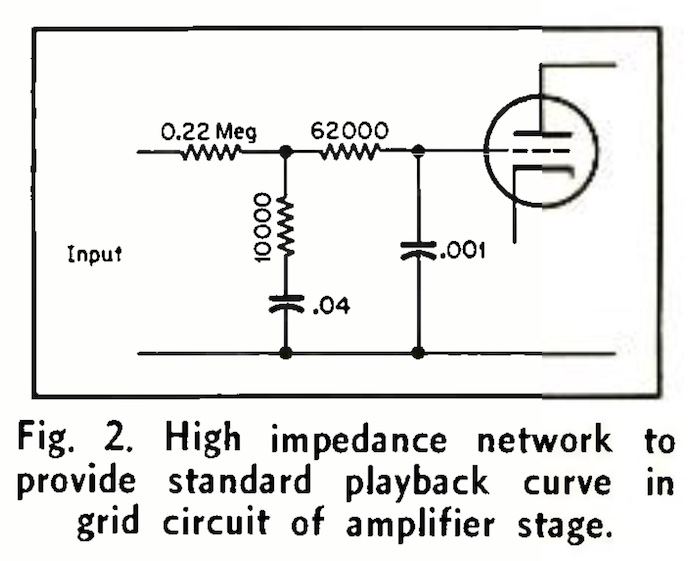

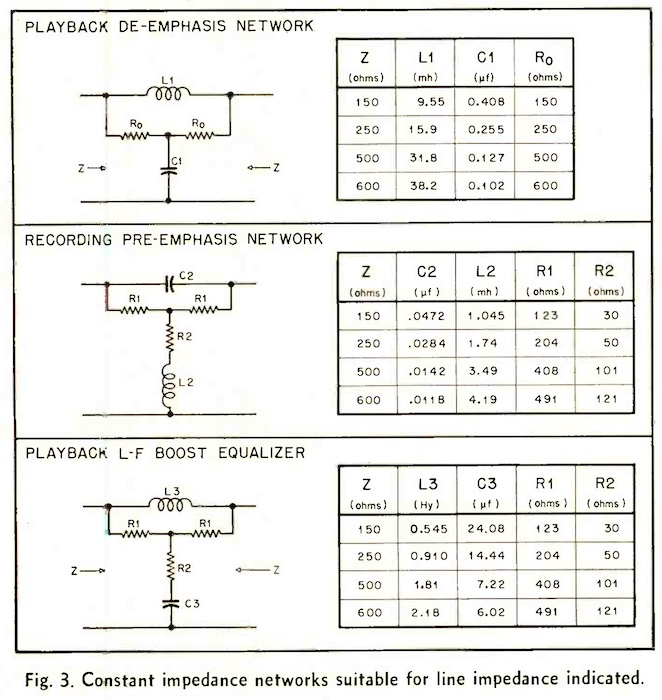

A few record companies are already using a curve which is essential that chosen by the AES, and the others have indicated a willingness to cooperate. As a definitely progressive step in simplifying the reproduction of recorded music with a minimum of complication in the equipment, the work of the Standards Committee is to be praised, and if sufficient approval of the idea is manifested by record buyers, manufacturers will fall into line. Details of the curve and a number of suggested equalizer circuits are presented in the article on page 22 in this issue.

すでにいくつかのレコードレーベルでは、AES が選定した標準再生カーブを使用しており、他のレーベルも協力する意向を示している。機器の複雑さを最小限に抑え、レコード音楽の再生を簡素化するための確実な進歩として、AES標準規格委員会の仕事は賞賛されるべきであり、そしてレコード購入者がこのアイデアに十分な賛同を示すならば、各レーベルも列をなして本再生カーブを採用することになるであろう。当該AES標準再生カーブの詳細と、それを実現するイコライザ回路の提案は、本号22ページからの記事で解説されている。