EQカーブの歴史、ディスク録音の歴史を学ぶ本シリーズ。前回 Pt.11 では、1948年6月18日に発表された、Columbia Long Playing Microgroove レコードの開発ストーリーを追いました。1939年から極秘裏に開発が進められたマイクログルーヴLPですが、経営者、エンジニア、ディレクタ、その他多くの人々が関わることで完成へと導かれ、業界にとって大きなマイルストーンとなりました。

On the previous part 11, I studied on the history of the Columbia Long Playing Microgroove Records, which was unveiled on June 18, 1948. So many individuals were involved in this secret project behind closed doors since 1939 — including executives, engineers, and directors. The advent of microgroove LP surely marked a milestone in the industry.

今回の Pt.12 はその続きで、前回紹介しきれなかった記事やインタビューののち、Columbia LP の録音・再生特性(EQカーブ)に関する記事や、ラジオ局用プロフェッショナル再生機器に加えられた変更など、当時の技術論文や技術解説記事から読み解いていくことにします。

This time as Pt.12, I am going to continue learning the history of disc recording — additional articles and interviews, as well as papers/particle regarding recording and reproducing characteristics for Columbia LP records, as well as the modifications to the professional reproducing equipment at radio stations, by reading and interpreting the technical papers and articles at that time.

source: “Reproduction of Microgroove Recordings”, Radio & Television News, Vol.40, No.4, October 1948, p.155

- 「Pt.0 (はじめに)」

- 「Pt.1 (定速度と定振幅、電気録音黎明期)」

- 「Pt.2 (世界初の電気録音、Brunswick Light-ray、ラジオ業界の脅威)」

- 「Pt.3 (Blumlein システム、当時のRCAやColumbia、民生用における高域プリファレンスの萌芽)」

- 「Pt.4 (Vitaphone、Program Transcription、Electrical Transcription、Bell Labs / Western Electric 縦振動トランスクリプション盤)」

- 「Pt.5 (ベル研とストコフスキーのエピソード、横振動トランスクリプション、Orthacousticカーブ)」

- 「Pt.6 (アセテート録音機のカッターヘッド特性、高調波歪の論文、超軽量ピックアップ)」

- 「Pt.7 (圧電ピックアップとジュークボックス、定速度記録再生の試み)」

- 「Pt.8 (1942年 NAB 標準規格策定の歴史)」

- 「Pt.9 (大戦中〜戦後、LP登場前夜の状況について)」

- 「Pt.10 (1949年 NAB 標準規格策定の歴史)」

- 「Pt.11 (1948年6月18日 Columbia LP Microgroove レコード登場)」

の続きです。

This article is a sequel to

- “Things I learned on Phono EQ curves, Pt.0 (Intro)”,

- “Pt.1 (constant velocity/amplitude, early years of electrical disc recording)”,

- “Pt.2 (earliest electrical recordings, Brunswick Light-ray, Radio industry)”,

- “Pt.3 (Blumlein system, RCA and Columbia in the early 1930s, germination of treble pre-emphasis)”,

- “Pt.4 (Vitaphone, Program Transcription, Electrical Transcriptions, Bell/WE Vertical Transcription)”,

- “Pt.5 (Bell Labs = Stokowski episode, Lateral Transcription and Orthacoustic)”,

- “Pt.6 (Instantaneous Recorders, papers on distortion and lightweight pickup)”,

- “Pt.7 (piezo-electric pickups, jukebox, constant-amplitude recording)”,

- “Pt.8 (history of 1942 NAB Standards)”,

- “Pt.9 (various situations in the 1940s)”,

- “Pt.10 (history of 1949 NAB Standards)”,

- and “Pt.11 (Jun. 18, 1948: the advent of Columbia Long Playing Microgroove Records)”.

毎回書いている通り、筆者自身の学習過程を記したものですので、間違いの指摘や異論は遠慮なくお寄せください。

As I noted in every part of my article, this is a series of the footsteps of my own learning process, so please let me know if you find any mistakes on my article(s) / if you have different opinions.

今回も相当長い文章になってしまいましたので、さきに要約を掲載します。同じ内容は最後の まとめ にも掲載しています。

Again, this article become very lengthy — so here is the summary of this article (the same contents are avilable also in the the summary subsection).

当時 Columbia Masterworks 部門副代表だった Goddard Lieberson 氏が1948年に書いた記事、CBS 社長だった Frank Stanton 氏への1994年インタビュー、Bachman 氏への1977年インタビュー、などを読むと、Wallerstein 氏の言い分、Goldmark 氏の言い分とは異なる、LP誕生に至る多様な視点が見られる。しかし依然として真実は闇の中である。

Additional information, such as the 1948 article written by Goddard Lieberson (Vice President of Columbia Masterworks), 1994 Interview with Frank Stanton (President of CBS), 1977 Interview with William Bachman (chief engineer of CBS) etc., gives us slightly different viewpoints from the statements by Edward Wallerstein and Peter Goldmark. Still, the truth is in the dark.

Columbia Long Playing Microgroove レコード実現に至った最大の技術的貢献は、William Bachman 氏が開発した「Hot Stylus」技術であったが、実はこれは1920年代にエジソンが縦振動長時間盤で用いていた。「Hot Stylus」は特許申請はしていなかったが社外秘の技術で、当初 Columbia が独占的に使用していたが、しばらくすると業界内他社に漏れ、のちに業界で一般的な技術となった。

One of the most technological contributions that made Columbia Long Playing Microgroove records a reality was the “Hot Stylus” technique, developed by William Bachman. But this “Hot Stylus” technique was originally from Thomas Edison’s vertical long playing discs in the 1920s. Columbia did not file a patent for the technique, although it was kept confidential for a while. Gradually the information was leaked in the industry, and later it became one of the fundamental technology on disc recording.

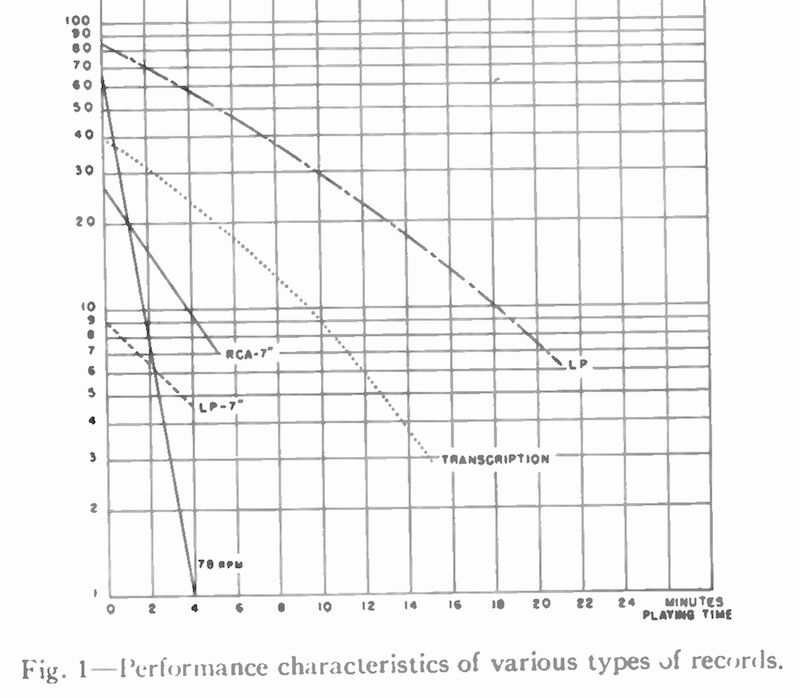

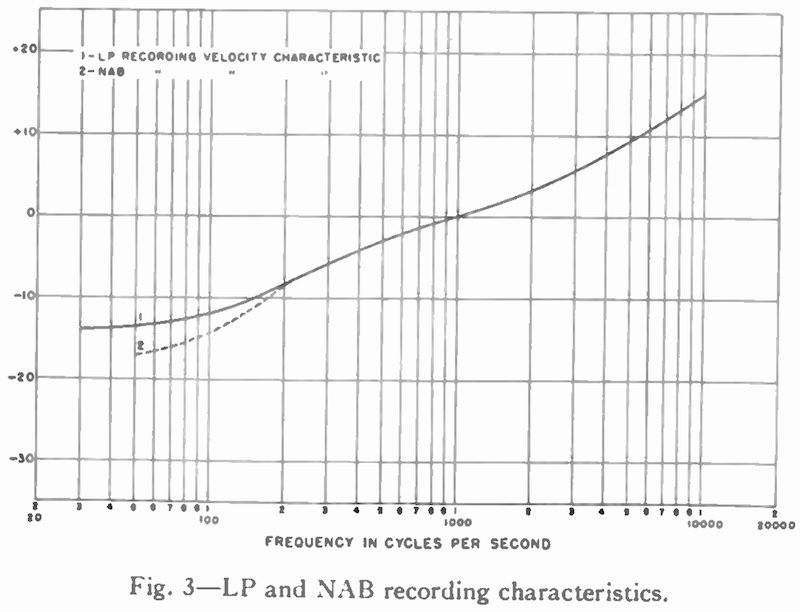

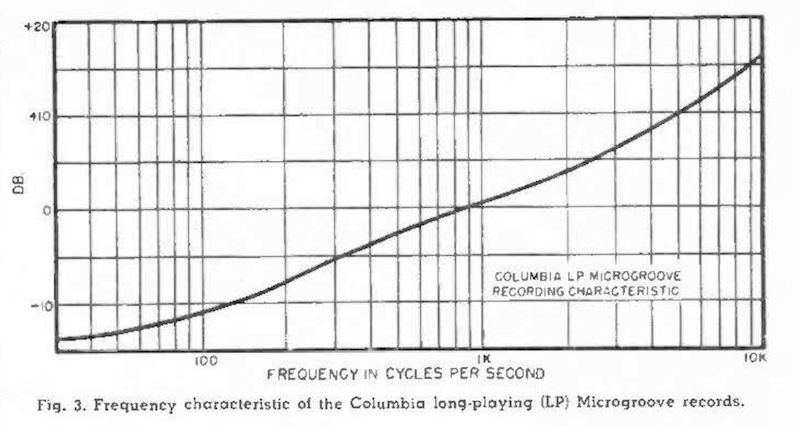

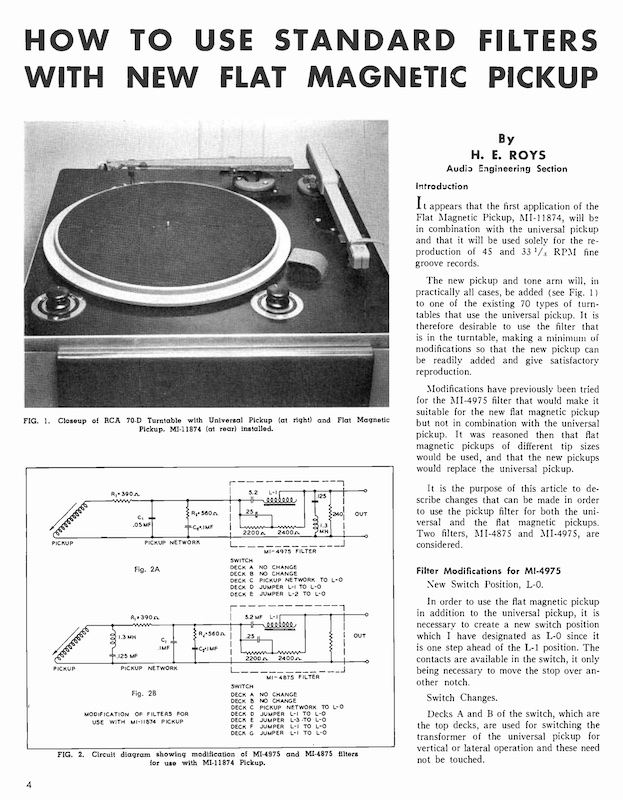

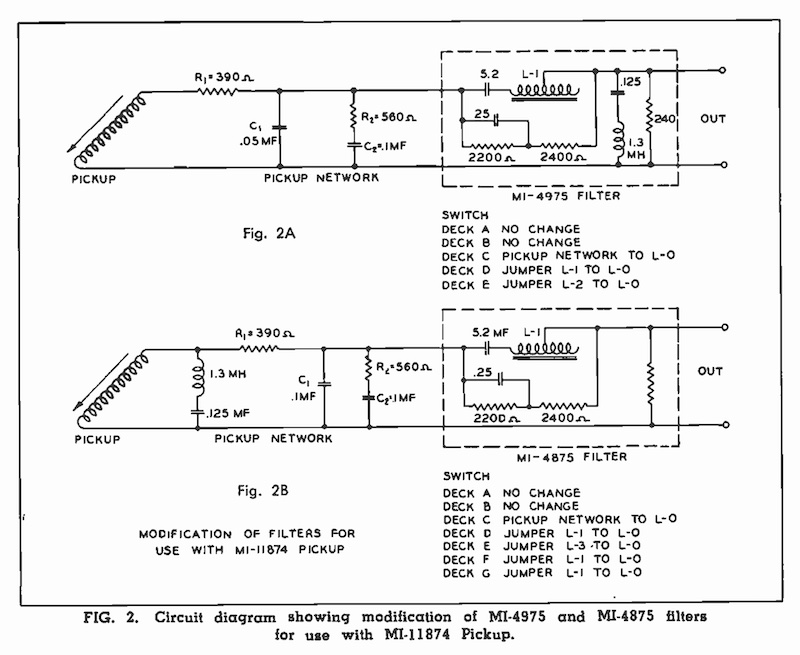

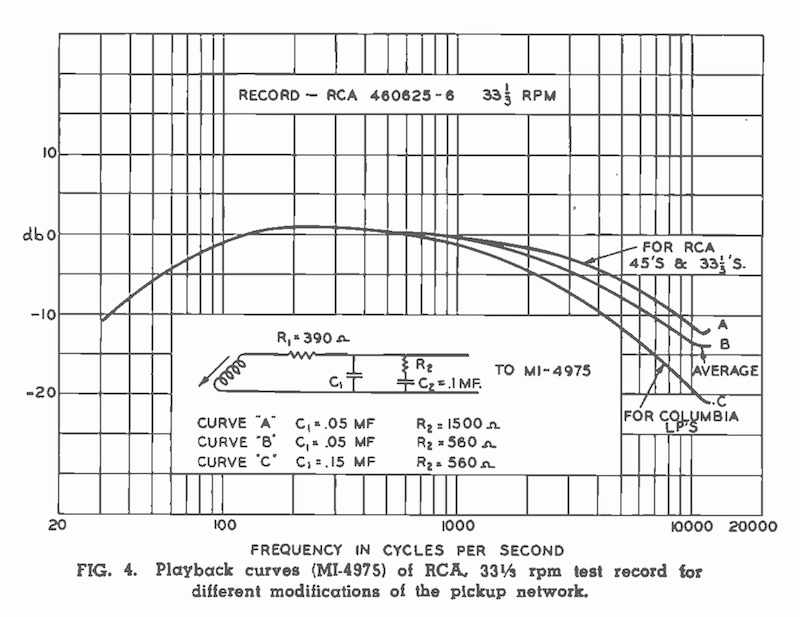

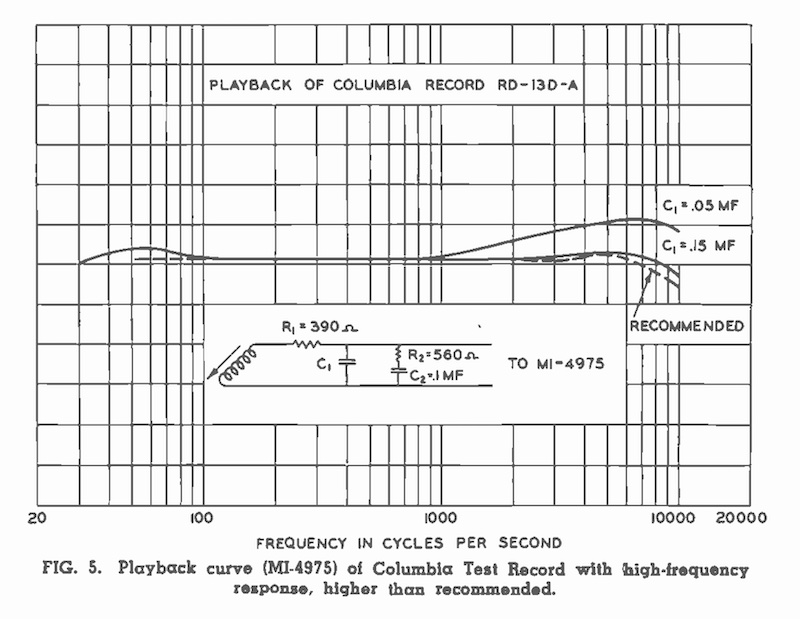

Columbia LP 用に使われた録音EQカーブは、中高域はトランスクリプション盤用のNABカーブと同じで、低域のみ異なっていた。しかし当時は、具体的な回路構成やパラメータなどは公開されておらず、グラフによる応答特性提示のみであった。当時の再生機器メーカも、従来の NAB 標準規格用の再生EQ機器をほぼそのまま流用するにとどまっていた。NAB とは異なる特性を使っていた RCA のマイクログルーヴ盤用には、当初はピックアップとフォノイコの間にRC回路を挿入するなどして対応していた。一方民生用市場においては、クリスタルピックアップが依然として一般的であり、厳密なカーブ補正は行われていなかった。

The recording characteristic used for Columbia LPs was essential identical to NAB Standards recording characteristic, except the low-bass portion. Even in 1949 or 1950, the characteristic was simply presented in the form of frequency response graph — not with circuit diagram, not with detailed parameters or configuration. Makers of reproducing equipment simply provide NAB reproducing filter (compensator) for reproducing Columbia LP Microgroove records. For RCA microgroove records, some modification was initially conducted, by inserting the additional RC circuit between the pickup and the compensator. On the other hand, for the consumer market, piezoelectric pickup was widely used, thus no exact (strict) compensation was conducted yet.

Contents / 目次

- 12.1 Some Other Notable Interviews and Articles

- 12.2 Technological Background of Long Playing Microgroove records

- 12.2.1 “The Columbia Hot Stylus Recording Technique” (1950)

- 12.2.2 “Notes on the Development of Hot Stylus Recording” (1950)

- 12.2.3 “The Columbia Long Playing Microgroove Recording System” (1949)

- 12.2.4 “Reproduction of Microgroove Recordings” (1948)

- 12.2.5 “How to Use Standard Filters with New Flat Magnetic Pickup” (1950)

- 12.3 The summary of what I got this time / 自分なりのまとめ

12.1 Some Other Notable Interviews and Articles

前回 Pt.11 では、以下の記事/書籍/インタビューを参照しました。

On previous Pt.11, I have referred and read the articles, books and interviews from the followings:

- The Billboard articles(May 28, 1948、June 5, 1948、June 26, 1948)/ Billboard 雑誌の記事

- Broadcasting Telecasting article(June 28, 1948)/ Broadcasting Telecasting 誌の記事

- LIFE Magazine article(July 26, 1948)/ LIFE 誌の記事

- Interview with Edward Wallerstein / Wallerstein 氏へのインタビュー (1967)

- Autobiography of Peter Goldmark / Goldmark 氏の自叙伝 (1973)

- Interview with William Bachman / Bachman 氏のインタビュー (1977)

- “THE LABEL: The Story of Columbia Records” by Gary Marmorstein (2007)

- and many more / その他

Pt.12 ではまず、Pt.11 で紹介しきれなかった、興味深い情報をいくつか学んでいきます。

In this Part 12, we will continue learning more of interesting information which could not be covered in Pt. 11.

12.1.1 “A 33-1/3 Revolution In Recording”, Goddard Lieberson (1948)

ひとつ目は、1948年当時に出版されていた、もうひとつの重要な記事です。

The first one is an important article, published in 1948 — the year Columbia LP was unvailed.

当時 Columbia Masterworks 部門副代表、のちに Columbia 社長(1956〜1971, 1973〜1975)になった、Goddard Lieberson 氏が、Saturday Review 誌 1948年6月28日号 に寄稿した記事「A 33-1/3 Revolution In Recording」(録音における 33 1/3回転の革命)です。「回転」と「革命」、共に「Revolution」であることにひっかけた、洒落たタイトルです。

The article is entitled “A 33-1/3 Revolution In Recording” (a pun of “drastic change” versus “rotating speed”), published in the June 28, 1948 issue of the Saturday Review magazine. The author is Goddard Lieberson, Vice President of Columbia Masterworks at the time (who later became the president of Columbia Records in 1956-1971 and 1973-1975).

この出版された日付から、LPがお披露目された1948年6月18日の直前直後あたりに書かれた記事であることが分かります。

As it was published in the June 28, 1948 issue, it is assumed that the article was written before or around the advent of LP records, that was unveiled on June 18, 1948.

Wallerstein 氏の視点とも、Goldmark 氏の視点とも異なる、当事者、かつ第三者による、LP発表直後の記事は、非常に参考になりました。

I think it very interesting and informative, as this article shows the third-party perspective: different from Mr. Wallerstein’s point of view; different from Mr. Goldmark’s point of view.

source: “A 33-1/3 Revolution in Recording”, Goddard Lieberson, Saturday Review (in Recording), Vol.XXXI, No.26, June 26, 1948, pp.40-41.

AS IS OFTEN the case with creative engineering, the new Columbia Long Playing Microgroove records are not only the product of technical development, but of a philosophy as well. I first heard that philosophy some nine years ago from Edward Wallerstein, then president of Columbia Records and now chairman of the board. At that time, he explained to me that his basic hope for recorded music was to make available the best possible performances in expert recordings at the lowest possible price. He further explained that the cutting of prices of shellac records was not the ultimate answer (though it was he who led the record industry in cutting the price of records in half, in 1940) and indicated that we must eventually evolve some new technique which would result in the recording of more music in less space.

クリエイティブなエンジニアリングの世界ではよくあることだが、Columbia による新しい Long Playing マイクログルーヴレコードは、技術開発によって生まれた製品であるのみならず、哲学の結晶でもある。私がその哲学を初めて耳にしたのは、今から約9年前、当時 Columbia Records の社長であった Edward Wallerstein 氏(現会長)である。その時彼は、記録音楽に対する基本的な願いとして「最高の演奏を最上級の録音で捉え、可能な限り廉価に提供すること」と述べていた。また彼は、シェラック盤の値下げが最終的な答えではない、とも説明していた(とはいえ、1940年にレコード業界をリードして、シェラック盤の販売価格を半額にしたのも彼なのだが)。そして、最終的には、より小さなスペースにより多くの音楽を記録できる、そんな新しい技術を進化させる必要がある、と指摘していた。

To this end, Mr. Wallerstein, in the same year (1939), gave orders to record all masters with a high-fidelity technique which had heretofore been restricted to laboratory practice, that would allow these masters to be available, at the appropriate time, for any possible technological development. It was this far-sighted preparation of the nearly complete Columbia catalogue which provided our engineers with a perfect series of masters with which to work toward the ends they wished to achieve.

この目標に向けて、Wallerstein 氏は同年(1939年)、それまで実験室に限られていたハイファイ技術を使って全てのマスターを録音しておくように指示し、将来あらゆる技術開発が進んだタイミングで適切な時期に、これらのマスターを利用できるようにした。このような先見の明のおかげで、Columbia のほぼ全カタログの高品質マスターが準備され、エンジニア達が実現したい(高品質な音源を新技術で提供するという)目標を達成できたのであった。

A 33-1/3 Revolution in Recording, Goddard Lieberson, Saturday Review (In Recordings), Vol.XXXI, No.26, June 26, 1948.というように、やはり1939年における Wallerstein 氏の先見の明 を讃える内容から始まります。実際、間違いなく大した慧眼でしょう。1939年当時、まだテープ録音も実用的でなかった時代、最も高品質で記録可能なメディアとして、放送局用トランスクリプション盤(16インチ33 1/3回転)があったものの、将来の新しい高品質メディア登場を見据えていたのですから。

As you can see, this article starts off with the praise to Mr. Wallerstein’s foresight. It actually was — in 1939, when no practical tape recording (for professional use) was there, and when transcription records (16-inch, 33 1/3rpm) could record in the highest possible quality, Mr. Wallerstein had a vision of the future arrival of the brand new high fidelity media.

続く、Peter Goldmark 氏に関するエピソードは、Pt.11 で見た Goldmark 氏の自伝に書かれている内容と異なる描写で、非常に興味深いです。

Then Mr. Lieberson tells the episode of Mr. Peter Goldmark, in different way from what Mr. Goldmark himself wrote in his autobiography as in Pt.11.

The first of these engineers was Dr. Peter Goldmark, director of research at the Columbia Broadcasting System, who already had to his credit the development of color television. Luckily, Dr. Goldmark is a devout music lover (and this is no coincidence since he has as granduncles the composers Karl and Rubin Goldmark) and an equally devout record collector. As so many of us have, he began to develop a mild despair when it began to appear that his home in New Canaan would no longer support his large collection of records, and, with this disappearing of storage space, Dr. Goldmark began to think seriously of a slow-playing record which would hold more than the usual four to four-and-a-half minutes on a side.

そのエンジニア達の中で最初に挙げられるのは、CBS 研究所の監督者にして、すでにカラーテレビの開発で功績のあった Peter Goldmark 博士である。幸運なことに、Goldmark 博士は敬虔な音楽愛好家であり(彼は作曲家の Karl Goldmark と Rubin Goldmark を大叔父に持つことから、これは偶然ではないだろう)、同様に敬虔なレコードコレクターであった。我々の多くもそうであるように、ニューケイナンの自宅が大量のレコードコレクションを収納できなくなり始めたとき、彼は軽い絶望感を覚え始めた。この収納スペースの消失に伴い、Goldmark 博士は、従来の片面4分〜4分半の(シェラック盤)レコードより長時間収録できる低速再生のレコードについて真剣に考え始めた。

A 33-1/3 Revolution in Recording, Goddard Lieberson, Saturday Review (In Recordings), Vol.XXXI, No.26, June 26, 1948.自伝では「蓄音機や(シェラック盤の)レコードには興味を持っていなかった」と書かれていましたが、この Lieberson 氏の記事によると、Goldmark 氏は相当のレコードコレクターであった ことが伺えます(笑)

In the autobiography, Mr. Goldmark stated like “All my life I had what we engineers call zero response to the phonograph”. But according to this article by Mr. Lieberson, Mr. Goldmark was a hardcore record collector as well 🙂

その後、33 1/3回転が新しいアイデアではないこと(放送局の世界ではトランスクリプション盤として長らく使われていたこと、そして 1931年〜1933年に Program Transcription 盤として市販されたことがあったこと)が述べられています。この部分は繰り返しになりますので割愛します。

Then the article continues, explaining the 33 1/3 rpm “not being new” (used by transcription records in the broadcast industry, as well by “Program Transcription” records by RCA Victor). I won’t quote this part as this story has already appeared several times in my entire article.

その次のパラグラフに書かれている内容が、またしても Wallerstein 氏や Goldmark 氏の言い分と異なります。

The following paragraph, yet again, is very interesting. It’s a different story from that of Mr. Wallerstein and Mr. Goldmark:

He began his experiments in 1944 with a record playing at forty revolutions per minute, which he soon discarded because most of the available existing equipment played at thirty-three and one-third rpm. Working at the latter speed he was able to put high quality recording on one twelve-inch side for the duration of sixteen minutes. This again was not enough to accommodate the majority of symphonic works on two sides of a record, so further laboratory investigation led to the development of an extremely fine groove.

1944年、彼(Goldmark 博士)は毎分40回転のレコードで実験を始めたが、既存の機器がほとんど 33 1/3回転であったため、すぐにこのアイデアを破棄した。33 1/3回転での実験により、12インチ盤の片面に16分間に渡り高品質収録が可能になった。しかしこれでは大半の交響曲を(12インチ 33 1/3回転のレコードの)両面に収録することができないため、さらに研究が進められ、最終的に非常に微細な溝の開発へとつながった。

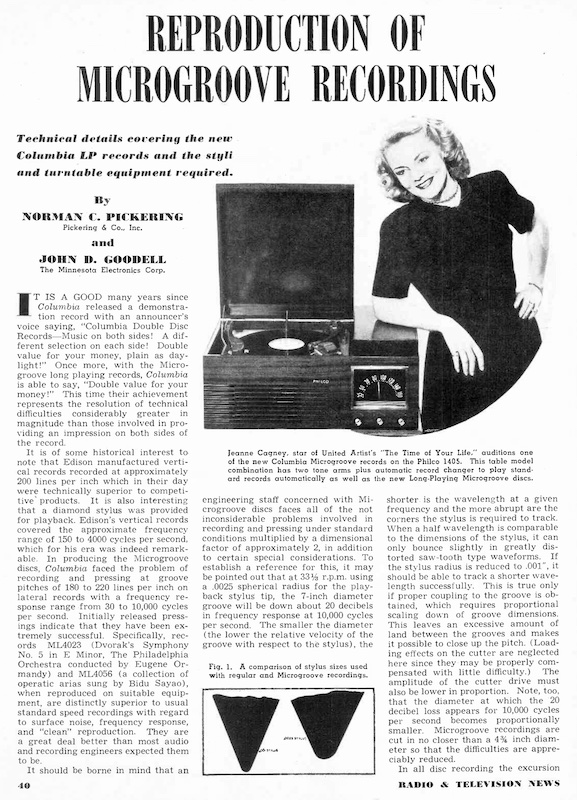

It was this microgroove, as we now call it, that made possible, in a real sense, a long playing record. This aspect of the new record is perhaps the most important reason why they play so well, for so long a period. With this technique the number of grooves per inch has been stepped up per record by a factor of about three, while the speed of rotation has been reduced by a factor of two and one-half which makes possible more than a sixfold time increase per side over the present record. The distance between successive grooves on a record is referred to by engineers as “pitch,” and on the standard seventy-eight rpm records, the pitch is from eighty-five to 100 lines per inch. On the new Columbia LP record, the pitch has been increased on the average to 224 lines.

まさに、我々が「マイクログルーヴ」と呼ぶこの微細な溝こそが、真の意味で長時間レコードを可能にした。これこそが新型レコードにおいて良質な再生を可能にした最重要な側面であろう。この技術により、1インチあたりの溝の数は約3倍に増え、逆に回転数は約2.5分の1となったので、現在の(78回転シェラック盤)レコードに比べて片面あたり6倍以上の記録時間が可能となった。レコードの溝と溝の間の距離のことをエンジニアは「ピッチ」と呼ぶが、標準的な78回転盤では、ピッチは1インチあたり85〜100本である。一方 Columbia の新しい LP レコードにおいては、ピッチは平均して224本にまで増やされている。

A 33-1/3 Revolution in Recording, Goddard Lieberson, Saturday Review (In Recordings), Vol.XXXI, No.26, June 26, 1948.1944年に Goldmark 氏がすでに開発を始めていた? 開発当初は 40rpm から始めた?

Goldmark started the LP development in the year 1944? He initially attempted developing a record at 40 rpm?

40rpm の話が本当なのかどうかは分かりませんが、1967年の Wallerstein 氏のインタビューや 1973年発行の Goldmark 氏の自叙伝と異なり、LP 発表直後に掲載された記事であること、そして第三者の記事である(とはいえ Wallerstein 氏同様に非エンジニアですが)ことから、傾聴に値する説かもしれません。

Unfortunately I am not sure (and I could not confirm) if the “40 rpm” was really true or not. However, it’s still worth reading, because Lieberson wrote this article that was published just after the introduction of LP records, while on the other hand Wallerstein’s interview was in 1967 (nearly 20 years after the LP); Goldmark’s autobiography was published in 1973 (25 years after the LP).

一方、「1944年、実験を始めた」という箇所は、Pt.11 セクション11.2.7 でみたように、1945年秋に友人宅でブラームスのピアノ協奏曲第2番を12インチ78回転盤6枚セットで聴いたことがLP開発のきっかけだった、と自叙伝で書いているのと矛盾していますね。

But the part “He began his experiments in 1944” may be inconsistent with the episode of “Brahms’ Piano Concerto No.2 on six 12-inch 78rpm discs, played with auto-changer, at friends’ house” as told by Mr. Goldmark (and as we followed in Pt.1 Section 11.2.7).

Pt.11 で「戦時中に中断していたLP開発が戦後直後に再開された」とみてきたことをあわせると、この「1944年」というのは「1945年」の typo なのかもしれませんが、実際のところどうだったのでしょうね。

Also, as we read in Pt.11 as: “Work on the LP project was suspended during the war and then resumed about three years ago”, it could be 1945, not 1944. I wonder which was the truth.

記事はその後、レコード内周での線速度低下による高周波数帯域ロスを解決しないと真の長時間レコードとはならない、と Goldmark 氏が格闘し解決、両面で45分間の記録が可能になった、と続きます(当該部分は引用割愛)。

The article then continues that, in order to develop a really long-playing record, it was needed to solve the problem of keeping the quality (coping with the loss of high frequency and the increase of surface noise) on inside the record. The article then writes that Mr. Goldmark solved the problem, and able to produce a 45 minute record on both sides.

内周での高周波帯域ロスの問題をどう解決したのかについてはなんの言及もありませんが、「高周波数帯域のレスポンスを損なうことなくノイズを除去する必要がある」という書かれ方からすると、のちほど セクション12.2.1 で触れる、カッター針の新技術の話が関係していそうです。

This article doesn’t mention how he managed to solve this problem, but by reading the line, “to solve this problem it was necessary to delete the noise without consequential loss of high-frequency response”, it could probably be the invention of the newly developed cutting stylus and its system, which will be mentioned later in Section 12.2.1.

続いて、William Bachman 氏の功績について触れられています。ここでは16インチセーフティマスターをLP盤にトランスファーした功績が挙げられていますが、Pt.11 セクション11.2.9 で述べた通り、このトランスファーの実際の貢献者は Ike Rodman、Bill Savory、Howard Scott の3名で、その作業を監督指揮したのが Bachman 氏ということでしょうね。なにより Bachman 氏は、LP 開発においてさまざまな技術的貢献を行った最重要人物です。

Then the story continues to the contribution by Mr. William Bachman. Here, this article only mentions his contribution as the job of transfering the existing (12-inch) high-quality safety masters onto the new record, but as we already have seen in Pt. 11 Section 11.2.9, the development of the transfer system as well as the actual transfering process was primarily done by Ike Rodman, Bill Savory and Howard Scott — and Mr. Bachman supervising the whole process. Furthermore, Mr. Bachman is definitely the most important engineer in the LP development — he actually contributed many works and inventions.

Once the record was devised, it came under the supervision of William Bachman, Columbia Record’s chief engineer, whose job it was to transfer our existing high-quality masters onto the new record, and to put it into actual production. In order to do this it was necessary to proceed through a trial production covering every phase of record making up to the point of manufacturing. This meant, first of all, the transfer of repertoire from a number of four-minute discs to a maximum of forty-five minutes of playing time (both sides of a twelve-inch Long Playing record).

実際の長時間レコードの考案が完了したのち、次は Columbia Records のチーフエンジニア William Bachman の監督下での作業が行われた。彼の業務は、既存の高音質マスターを新開発のレコードにトランスファーし、実際に生産することである。そのためには、レコード製造における全工程を網羅したあらゆる試作が必要となった。つまり、まず最初に、片面4分収録されたマスターを、(12インチLPの両面に収録可能な)45分間にトランスファーする作業である。

Under Mr. Bachman’s careful guidance, each step of the process was refined: better cutting styli were evolved, amplifiers, turntables, and all cutting equipment were redesigned and rebuilt, and it was soon found necessary to revise standards of uniform speed, as any speed variation, even a minute one, shows up much more disastrously on thirty-three and one-third than on seventy-eight rpm. The problem of surface noise on shellac records has been (to curdle a metaphor) a constant thorn in the ears of music lovers and record manufacturers. The new Columbia Long Playing record will be non-breakable and on vinylite; as a result, we were faced with the problem of no surface noise!

Bachman 氏の慎重な指揮のもと、各工程の改良が進められた。より優れたカッティングスタイラスが開発され、アンプ、ターンテーブル、その他すべてのカッティング機材が再設計され、そして均一なスピードの基準を見直す必要があることが判明した。なぜなら、78回転盤よりも、33 1/3回転盤の方が、たとえ微小な速度変化であっても、はるかに悲惨な結果をもたらすからである。シェラック盤におけるサーフェスノイズの問題は、音楽愛好家やレコードメーカを長らく悩ませてきた耳の痛い問題であった。Columbia による新しい長時間レコードは、ヴィニライト製で非常に丈夫であり、その結果、サーフェスノイズが全くない、という問題に直面することとなった!

A 33-1/3 Revolution in Recording, Goddard Lieberson, Saturday Review (In Recordings), Vol.XXXI, No.26, June 26, 1948.「サーフェスノイズが全くない、という問題」って、誤植かなにかだろうか、と思ったら、違いました。以下続きを読んでみましょう。

Initially it was a typo or something when I read the phrase “the problem of no surface noise”, but it was not. Let’s read the following:

It may not be generally known, but surface noise on shellac records covers a multitude of sins. First of all, it obfuscates or obliterates the distortion of high frequencies which is usually found in shellac pressings, and along with that, it covers recording ticks and production blemishes. Vinylite reduces surface noise, but it will not take away all noises. This extra-musical noises were eliminated from our new record through long research in perfecting the shape of the groove and the design of the new pick-up and player already described. This new system, which will be manufactured for us by the Philco Corporation, is especially designed to play Columbia Long Playing records. This brings a long-awaited coordination of all of the elements which go into the proper reproduction of phonograph records, and will cost under thirty dollars.

あまり知られていないことであるが、実はシェラック盤におけるサーフェスノイズは、さまざまな欠点を覆い隠してくれているのだ。まず最初に、シェラック盤にありがちな高音域の歪みを目立たなくしたり消したりしてくれている。それと同時に、カッティングで生じたノイズや製造上の欠点も覆い隠してくれる。一方、ヴィニライト盤はサーフェスノイズを低減させられるが、これらすべてのノイズを除去できるわけではない。この音楽以外のノイズは、我々の長年の研究によって、記録溝の形状を完璧なものとし、さらに新型ピックアップ(カートリッジ)やプレーヤを新たに設計することで解決した。この新システムは、Philco社によって製造されるが、Columbia Logn Playing レコード再生用に設計されたものである。これにより、長らく必要とされてきた、レコードを正しく再生するために必要なすべての要素の調和がもたらされることとなる。しかも価格は30ドル以下である。

A 33-1/3 Revolution in Recording, Goddard Lieberson, Saturday Review (In Recordings), Vol.XXXI, No.26, June 26, 1948.上で書かれている、「サーフェスノイズがさまざまな欠点を覆い隠してくれている」という視点は、78回転シェラック盤の時代をリアルタイムに経験しておらず、最初から LP だった我々の世代にとっては、非常に新鮮なものと感じます。レコード盤の材質変更・改良によってサーフェスノイズがなくなったことにより、記録性能そのもののアラが目立つようになったから、ますます高品質な記録装置や記録技術が必要とされるようになった、ということですね。

The paragraph “surface noise on shellac records covers a multitude of sins” reads very new and fresh to me (or us), whose first audio media was LP records (i.e., who have not experienced the real-time 78rpm shellac record years). Improvement of the record material resulted in less surface noise, but on the other hand other blemishes became audible. So they needed far better recording technology and equipment to complete the LP records.

「記録溝の形状を完璧なものとし」のくだりは、のちほど セクション12.2.1 で紹介する通り、カッティングスタイラス(カッター針)の形状に関する議論、そして1948年当時は Columbia が企業秘密としていた、電熱線で針を温める技術とつながっている話です。

The phrase “perfecting the shape of the groove” is surely related to the discussion (and the company secret of heated stylus technique), as we see later in the Section 12.2.1.

そして、プレス工場における James (Jim) Hunter 氏の功績について言及されます。

Then the article continues to name James (Jim) Hunter, who contributed the LP develpment at the pressing plant.

With Mr. Bachman’s work finished, the master record was sent to our factory in Bridgeport, Conn., where James Hunter, vice president in charge of production, established an entirely separate manufacturing division for the processing of the new record. This space is kept dust-proof and meticulously clean; fine specks can contaminate the compounds and make for noisy records. A rigorous testing and inspecting procedure was also established for checking on the new records as they are produced.

Bachman 氏による作業を終えたマスター盤は、コネチカット州ブリッジポートにある弊社ファクトリー(プレス工場)に送られる。この工場では、生産担当の James Hunter 副代表によって、(従来のシェラック盤プレス用のラインとは)全く別の製造ラインが設立されている。このラインは完璧に防塵・清掃が徹底されている。微細なゴミが生産ラインのヴァイナル化合物(コンパウンド)に混入すると、ノイズを発生する盤となってしまうからである。また、生産された新しいレコードをチェックするために、厳密な品質試験・検査手順も確立された。

A 33-1/3 Revolution in Recording, Goddard Lieberson, Saturday Review (In Recordings), Vol.XXXI, No.26, June 26, 1948.最後に、なぜ市販用新メディアとして磁気テープではなくマイクログルーヴ盤を選んだのか、説明されたのち、最後に価格面におけるメリットが強調され、Lieberson 氏による本稿はまとめられています。

Finally, Mr. Lieberson concludes the article, describing why Columbia did choose the microgroove discs instead of magnetic tapes as a new consumer medium, mostly from the aspect of price.

In discussion of low-speed records, one invariably hears the mention of tape recording. Well, someone has very cleverly pointed out that a record is exactly the same thing as tape, only conveniently rolled up on a flat disc. On this basis the length of tape line on a Columbia twelve-inch Long Playing record is more than three-quarters of a mile! Furthermore, this same amount of mileage in tape, and of the same high quality, would cost two or three times as much, and is, I believe, two or three times more difficult to handle. There is the further advantage that any part of the music on a record can be played at will without the rewinding that tape necessitates.

定速度レコードについての議論においては、必ずと言っていいほ磁気テープ録音の話が出てくる。誰かが的確な指摘をしてくれているが、レコード盤とは磁気テープと同じ(長時間高品質記録メディア)であって、好都合なことに平らな円盤上にテープが巻かれていると考えればいい、ということなのだ。Columbia の12インチ Long Playing レコード上のテープの長さ(記録溝の長さ)は、3/4マイル(約1.2km)以上の長さもあるのだ! しかも、これと同じ長さのテープで、かつ同等の高品質を備えたものを製造するとなると、その価格は2〜3倍となる。また、取り扱いも2〜3倍難しくなると私は考える。また、磁気テープとことなり、レコード盤では、記録された音楽のどの部分でも自由に再生可能である。しかもテープを巻き戻す必要もないのだ。

The advantages of the new Columbia Long Playing record are manifold and obvious. Perhaps it is enough merely to list the following: uninterrupted music, the cutting down of storage space, the prospect of convenient shipping of records, the absence of any direct needle chatter which makes it possible, if you wish, to have the record playing in the open instead of its being boxed in, a wider dynamic range free of surface noise, and the very important aspect of price. The twelve-inch Columbia Long Playing Record will sell for $4.85, the ten-inch for $3.85. For comparison, Tchaikovsky’s “Fourth Symphony” by the Philadelphia Orchestra which would sell on vinylite conventional records in an album, for $11., can be had on one twelve-inch Long Playing record for $4.85; the Mozart “G Minor Sympony,” conducted by Fritz Reiner sells for $7 on vinylite in an album, and for $3.85 on a ten-inch Long Playing record. It would seem to me that we are at the beginning of a new era of music listening on records — uninterrupted listening at the lowest cost in the history of the phonograph record.

新しい Columbia Long Playing レコードの利点は多岐に渡り、また明白である。以下に列挙するだけで十分であろう。「途切れることのない音楽再生」「保管スペースの削減」「レコード輸送の便利さ」「針が直接鳴ることがなくなり、(ターンテーブルとピックアップを)閉鎖空間にせずとも、オープンな状態で再生可能」「サーフェスノイズのない広いダイナミックレンジ」そして最も重要な「手頃な価格」などである。12インチの Columbia Long Playing レコードは $4.85 で、10インチは $3.85 で、それぞれ販売される。比較のために、チャイコフスキーの交響曲第4番(フィラデルフィア響)では、ヴィニライト製の従来の(78回転)盤によるアルバムは $11 もするが、これが1枚の12インチLP盤に収録でき、$4.85 となる。フリッツ・ライナー指揮のモーツァルトのト短調交響曲(第40番)は、ヴィニライト製の(78回転盤の)アルバムは $7 であるが、これが1枚の10インチLP盤に収録され、$3.85 となる。途切れることのない音楽を、蓄音機市場最も低いコストで聴ける、という、レコード鑑賞における新時代の幕開けを感じさせる、私はそう思っている。

A 33-1/3 Revolution in Recording, Goddard Lieberson, Saturday Review (In Recordings), Vol.XXXI, No.26, June 26, 1948.Pt.11 で参照した Wallerstein 氏のインタビュー、および Goldmark 氏の自叙伝とインタビュー、さらに Bachman 氏へのインタビュー。そして、上でみてきた Lieberson 氏執筆の記事。これらのいずれもが真実を含んでおり、また同時にいずれも記憶違いや一部創作を含んでいる、と考えられます。真実は闇の中なのかもしれませんが、すべての資料を俯瞰して捉えると、おおまかな真実は見えてきそうな気がします。

In Pt.11, we have learned several document — interview with Mr. Wallerstein; autobiography of Mr. Goldmark (and interview with him); interview with Mr. Bachman. Then here in Pt.12 we have read the article by Mr. Lieberson. Each one surely contains the truth, and each one also has mistakes (or even a bit of fabrications) — THE TRUTH LIES DEEP DOWN. Anyway, by reading this and that comprehensively, we may understand some of the facts behind the history.

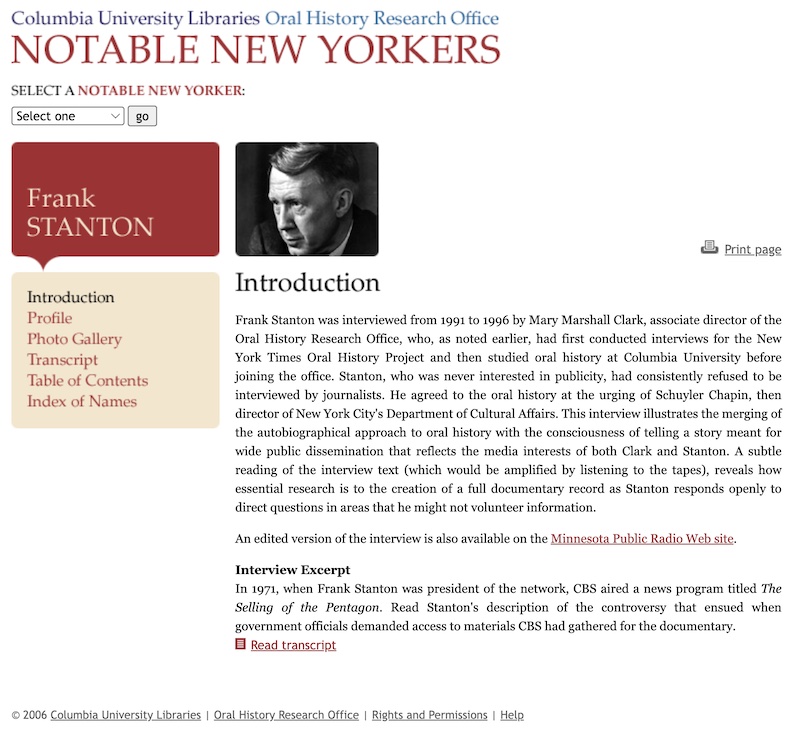

12.1.2 Oral History Interview with Frank Stanton by Mary Marshall Clark

2つ目は、1946年〜1971年に CBS 社長を務めた Frank Stanton 氏に対するインタビューで、コロンビア大学のオーラルヒストリー(口述歴史)研究所の Mary Marshall Clark 氏により、1991年〜1996年の長期間にかけて行われました。

The second one is an interview with Frank Stanton, president of CBS from 1946 until 1971. The interview was conducted by Mary Marshall Clark of Columbia University Libraries Oral History Research Office, spanning from 1991 until 1996.

目次 を見るとわかるように、幼少期から1990年代に至るまで、膨大なインタビューは貴重な資料となっていますが、1994年2月17日に行われたインタビューセッション14、619〜627ページ において、Columbia の LP 開発エピソードが扱われています。これもまた、Wallerstein や Goldmark とは異なる視点から語られるもので、非常に興味深いものです。

As you can see in the Table of Contents, the enormous amount of interviews spanning from his youth to 1990s contain invaluable information. And in the Session 14, February 17, 1994, he talks about the story of the Columbia LP development on pages 619 to 627. This is also interesting, because the story is told from his own perspective — different from the perspectives of Mr. Wallerstein and Mr. Goldmark.

After the War or perhaps during the War — I’m talking now World War II — [Peter] Goldmark, who was the head of our laboratories and the inventor that had done a lot of work in television, was an audio expert, and Peter came up with the idea that you could have a single 12-inch record that played up to a half-hour on each side. That became known as the “LP” or long-playing record.

第二次世界大戦終結後、あるいは大戦中だったかもしれないが、CBS研究所のトップであり発明者である、テレビ部門で多くの仕事をなした (Peter) Goldmark は、オーディオ専門家だった。そして Peter の脳裏にアイデアが浮かんだ。もしも、12インチのレコードで片面30分再生できるようになったら、と。それが現在「LP」または長時間レコードとして知られるようになったものだ。

That’s an interesting chapter in itself, because Wallerstein was a traditional, 78 rpm, shellac- record man. He had no use for vinyl, which was a development of the war years, and he had no interest in innovation. Goldmark was just the reverse, and I said to Wallerstein, who was then running that division of the company, if you don’t want to fund this development work, I’ll fund it out of corporate. But if it’s a success, and you take it into your group, I’m going to charge you for all the expense that the corporation went to to develop it.

このエピソード自体が非常に興味深いものだ。というのも Wallerstein は伝統的な78回転シェラック盤の人だった。戦時中に開発されたヴァイナルを使うこともなく、またイノベーションに興味もなかった。一方 Goldmark はその逆であった(イノベーションにこそ興味があった)。そこで私は当時 Columbia 社長である Wallerstein にこう言った。「(君が)この開発案件に予算を出したくないのであれば、私がCBS社から予算を出そう。ただし、もしこの開発が成功し、その成果を Columbia が取り込んだら、開発にかかった費用を全て君に請求するつもりだ。」

No problem. He just thought it was Goldmark’s folly. And, of course, it was anything but that, and that gave the record company an enormous shot in the arm and allowed us to do something which we had long wanted to do, but were unable to do, because technology wouldn’t permit. And it’s as simple as having a record club, where you got your records by mail.

問題ない(と返事が返ってきた)。Wallerstein は(この開発が)Goldmark の愚行だと思ったのだった。そしてもちろん、愚行なんかではなかった。この開発のおかげで Columbia というレコード会社は大成功を収め、さらに、長らくやりたいと思っていたが、技術的に困難なためあきらめていたことが可能となった。それは、「レコードクラブ」を持つ、というシンプルなものであった。つまり、レコードを郵送するサービスだ。

Not an original idea; there were book clubs at that time. But we made a lot of test mailings of 78 [rpm] shellac records, and they always ended up being broken in shipping. And even if those records were made out of shellac, with a core of very strong binder, like a heavy craft paper, to try to keep them from breaking, we couldn’t lick it. But the vinyl record, in the 12- inch size, you could bend that and twist it and so forth, you could ship it. It was lightweight; it didn’t break.

確かに(レコードクラブは)オリジナルなアイデアではなかった。当時すでに「ブッククラブ」(書籍が郵送されるサービス)があったが、78回転シェラック盤時代になんども試験的に郵送を試みたのだが、配送中に常に割れてしまった。シェラック盤を、厚手のクラフト紙のような素材で作られた非常に丈夫なバインダーを使って、破損しないようにしたとしても、レコード破損の問題を解決できなかった。しかし、12インチのヴァイナル盤であれば、曲げても捻っても出荷できた。軽量でかつ割れないからだ。

That let us start a record club. And, of course, the fact that you had a full hour on a record made it much more attractive. The long-playing record did everything that a new product ought to do. It gave you better quality, better distribution and lower price. It just worked all way around, and the record company really took off as a result of that long-playing record.

こうして、レコードクラブを開始することができた。そしてもちろん、1時間たっぷり聴けるレコードは非常に魅力的なものであった。LP (長時間) レコードは、新製品かくあるべし、という全てをやってのけた製品であった。高品質で、流通もさせやすく、価格も安い、そしてこのLPレコードによって、レコード会社 (Columbia) は飛躍的に成長した。

And as I said, the record company itself didn’t want any part of it. It was done to them, not with them. Once it became successful, of course they wrapped their arms around it. Then I replaced Wallerstein with another man. Wallerstein was well up in years. But he was unbending and, as I indicated earlier, just couldn’t believe that there was any way to do this besides the way he was then doing it.

先ほど述べた通り、レコード会社 (Columbia) 自体は(LP開発に)関わろうとしていなかった。つまり、彼らのために行った開発であり、彼らと共に行った開発ではなかった。しかし一旦成功を収めると、当然ながらレコード会社 (Columbia) は、(開発されたLPという新製品を)我が物とした。だから私は(Columbia レコードのトップを)Wallerstein から別の人物に代えた。Wallerstein は年をとりすぎていた。しかし彼は屈託がない人物で、先に述べた通り、過去に自分がやった方法以外に新たな別の方法があるとは信じられない、そんな人物だった。

Interview with Frank Stanton by Mary Marshall Clark, Session 14, February 17, 1994.Oral History Research Office Collection of the Columbia University Libraries.

この Stanton 氏のインタビューから、CBS と、その完全子会社である Columbia Records Inc. の関係性(正確には、会社の経営者同士の関係性、でしょうか)が垣間見える気がします。

This interview with Mr. Stanton might display the delicate relationship between two companies — CBS and Columbia Records Inc.; more precisely, the relationship between presidents and chairmen between these two companies.

前回 Pt.11 セクション 11.2.10 において、「プレス向け公開の時には、Peter Goldmark 氏と CBS ラボの貢献が強調される結果となりました」と書きましたが、もしかしたら、Columbia 社および Columbia 社のエンジニアの功績が当時あまり表に出なかったのは、CBS の Stanton 社長および Paley 会長が、Columbia 会長の Wallerstein 氏のやりかたに不信感を抱いていたから、なのかもしれませんね。

In Pt. 11 Section 11.2.10, I wrote as “the emphasis was laid on Dr. Peter Goldmark as well as CBS Labs”. So it could be that CBS executives (President: Stanton, and Chairman: Paley) were developing a feeling of distruct toward Mr. Wallerstein, and because of it, CBS gave honour to Dr. Peter Goldmark and the CBS Laboratories for the LP development.

一方、このインタビュー中で、かの Columbia Record Club の話が出てくるのも興味深かったです。確かに、シェラック盤の時代にはメールオーダーというのは実質不可能だったわけですからね。

And on the other hand, it is interesting to see the term Columbia Record Club in this interview. As a matter of fact, fragile 78rpm shellac records were not appropriate for mail orders.

12.1.3 “An Interview with Dr. Peter Goldmark”, Gerald Piel (1970)

3つ目も、非常に興味深いものです。

The third one is also very interesting enough.

Past Daily というブログサイトで、Scientific American 誌の編集長 Gerald Piel 氏が、1970年に Peter Goldmark 氏に対して行ったインタビュー音源 が紹介されています。恐らく当時のラジオ番組かなにかで放送されたものではないでしょうか。

The “Past Daily” website has an article, featuring a recorded audio of the interview with Peter Goldmark in 1970, conducted by Gerald Piel (editor-in-chief of Scientific American magazine). I guess this probably is off-the-air recording of a radio program or the likes.

インタビューの前半はLP開発について語られ、後半は(インタビューが行われた1970年からみた)将来の科学技術の発展について、Goldmark 氏が自らの考えを語る、という、非常に興味深い音源です。また、Goldmark 氏の肉声が聴けるのも貴重です。

The first half of the interview deals with the development of the LP records; and in the latter half, Mr. Goldmark shares his views of future inventions during the 1970s. Also, it’s simply precious to hear Mr. Goldmark’s real voice.

その中でも特に興味深いのが、LP 開発における最初期の実験録音が紹介されていることです。ちょうど音源の 02:15〜03:18 あたりで聞かれる、ベートーヴェンの弦楽四重奏曲第15番イ短調です。

In the context of the long series of my articles, the first half is very interesting — Mr. Goldmark talks about his earliest experiments during the LP development. On 02:15 ~ 03:18, we can hear the actual audio of one of his early experimental recordings: Beethoven’s String Quartet, No.15, A Minor.

Why don’t we hear a passage from one of your early recordings of the Beethoven Quartet? The A minor 15th was one of the first you did, wasn’t it?

ではここで、あなたが最初期に録音したベートーヴェンの四重奏曲を聴いてみることにしましょう。この15番イ短調が、最初期に録音した楽曲の1つだったんですよね?

Right. We experimented with that one, and we were able to put this on a single record on two sides of a single record. By the way, when you listen into this, when you listen to the Beethoven, you will probably notice a great deal of surface noise still crackling and many other imperfections. Well, this was at the very first few months of the project, and thank goodness we improved a lot.

ええ。この楽曲で実験録音を行い、レコードの両面に収録することに成功しました。ところで、このベートーヴェンの録音を聴いてもらえばわかる通り、大量のサーフェスノイズがパチパチ鳴っていたり、まだまだ完成度が低いものでした。ともあれ、プロジェクト開始直後の数ヶ月間の成果がこれで、幸いなことに、その後品質をどんどん向上させられました。

Let’s hear a passage from it.

では、その音源の一部を聴いてみることにしましょう。

Interview with Dr. Peter Goldmark, Gerald Piel, 1970 (Past Daily)Goldmark 氏がこのインタビューで述べている通り、本当に「(Goldmark 氏が)開発を開始して最初の数ヶ月間の試験的な録音」の音源なのか、はたまた Goldmark 氏が LP 開発に関わる前(1939年〜1941年)の音源なのか、の判断はつけかねますが、ともあれ貴重な音源に変わりはありません。「まだ当時はスクラッチノイズが盛大に聞こえるものだった」と述べているのも興味深いです。

I have no idea if this recording was really from his early experiments, or from much earlier recordings (before Mr. Goldmark joined the Columbia/CBS LP development project). Anyway, this is indeed an invaluable sound source. Also interesting to know Mr. Goldmark saying “you will probably notice a great deal of surface noise still crackling and many other imperfections”.

その直後、Piel 氏が、LP開発において最初に録音したクラシックの楽曲を質問しています(03:18〜03:33)。

After the excerpt of the recording, Mr. Piel asks Mr. Goldmark the first classical music he ever recorded (03:18~03:33).

What was the first classical music that you got on a long playing record, Peter?

Peter、いちばん最初に長時間レコードに記録したクラシック曲は何でしたか?

I think it was the Tchaikovsky violin concerto performed by Isaac Stern.

確か、アイザック・スターン演奏、チャイコフスキーのヴァイオリン協奏曲だったと思います。

Interview with Dr. Peter Goldmark, Gerald Piel, 1970 (Past Daily)さらに続いて、1945年11月の実験録音を披露するパート(03:33〜05:15)も興味深いです。実際の音源は、04:05〜04:50で聴くことができます。

Then the conversation continues, introducing another experimental recording from November 1945 (03:33~05:15). The excerpt of the recording can be heard at 04:05~04:50.

You did Gershwin’s “American in Paris”, too, as an early experiment.

同じく初期に、ガーシュインの「パリのアメリカ人」の実験録音もされていたんですよね。

Yes, I found an early record dated November 1945. We had on one side of the record experiment record Gershwin’s American In Paris, and on the other side, Tchaikovsky’s 1812 Overture.

ええ、1945年11月録音の最初期のレコードを発見したのですが、この実験録音盤の片面にガーシュインの「パリのアメリカ人」が、裏面にはチャイコフスキーの大序曲「1812年」が記録されていました。

This again was a laboratory feat.

これもまた研究室内の実験録音だった、と。

Yes, this was definitely it.

ええ、その通りです。

Let’s hear a few minutes of Gershwin from this 1945 record.

それではこの1945年実験録音盤から、ガーシュインを一部聴いてみましょう。

Interview with Dr. Peter Goldmark, Gerald Piel, 1970 (Past Daily)そのあとに話される内容も興味津々です(04:50〜05:17)。

Exceptionally interesting is the following conversation (04:50~05:17).

But again, Peter, there is some surface noise, but by golly, one hears all the instruments separated nicely.

Peter、この音源でもまだサーフェスノイズが聞こえますね。しかし、いやはや、(さきほどのベートーヴェンに比べて)すべての楽器が素晴らしく分離した録音になってますね。

Well, as far as fidelity, as far as distortion, that improved more quickly than the quality of the material because vinyl records were not in use and it was great difficulty to make the vinyl clean enough.

音質や歪みに関しては、迅速に改良改善が進みました。それより、レコードの素材の改良改善が大変でした。当初はヴァイナルが使われていなかったこと、そして、純度の高いヴァイナル素材を製造するのが非常に難しかったこともあります。

Interview with Dr. Peter Goldmark, Gerald Piel, 1970 (Past Daily)このインタビュー音源を聞く限りにおいては、Wallerstein 氏の言い分、つまり「Goldmark 氏はLPプロジェクト開発において単なるスーパーバイザでしかなかった」(技術的貢献は何もしていなかった)、ということはなく、リーダとしてエンジニア達と一緒になって開発を行なっていたようにも感じられますね。

As we listen to this recorded interview, I feel convinced that Mr. Goldmark surely contributed in the LP development — at least, as a project leader, he collaborated with his fellow engineers — although it contradicts Mr. Wallerstein’s saying “Peter Goldmark was more or less the supervisor, although he didn’t actually do any of the work”.

12.1.4 William S. Bachman Oral History Interview by James A. Drake (1977)

4つ目は、更に興味深い情報が満載です。

The fourth one is full of information — far more interesting than ever.

Pt.11 セクション 11.2.8 でも少し触れた、1977年に William Bachman 氏へ行われたインタビューには、技術的に非常に興味深い話が載っていますので、これも追加引用します。

Interview with William Bachman (1977), as I briefly mentioned in Pt.11 Section 11.2.8, contains much more information we should learn. Below is the excerpt of the quotes.

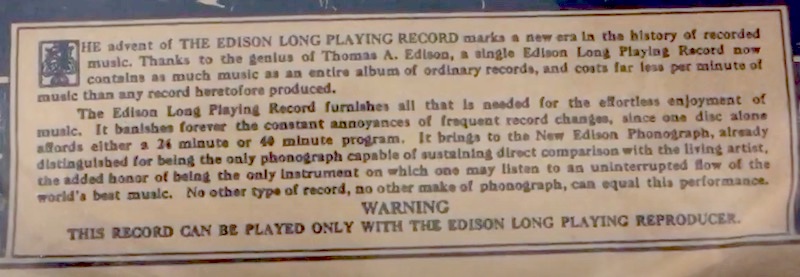

まず、Columbia の LP 開発は、1930年代前半の RCA Victor Program Transcription 盤にインスパイアされたのでは決してなかったこと、むしろ Edison Diamond Disc の長時間盤に非常に注目していたこと、が語られているくだりです。

Initially, Mr. Bachman tells that ealry 1930s RCA Victor Program Transcription didn’t affect the Columbia’s LP development at all; rather, Edison’s Long Playing Diamond Disc (1920s) was one of the inspirations.

When you began the LP project, did you go back to the RCA Victor long-playing discs (i.e. “Program Transcription” records) of the early 1930s?

LP開発プロジェクトを始めた際、RCA Victor が1930年代前半にリリースした長時間レコード (Program Transcription) にまでさかのぼりましたか?

No, never. Those Victors were a complete failure, you know. There wasn’t anything new about them, even when Victor launched them. Maybe the grooves were a little bit narrower than the regular 78s that RCA was putting out. But there was nothing new about the speed because 33-1/3 r.p.m. was already the standard for cutting [radio] transcription discs and also for the old Vitaphone discs. So there was nothing new about the speed. And the playback stylus specs were the same that Victor’s 78 players had in those days.

いいえ。ありえません。そんなことはしませんでしたよ。あの Victor(の長時間レコード)は完全な失敗作でしょう。Victor が製品化した当時ですら、なんら新規性のないものでした。RCA が通常の78回転盤で使っていた溝の幅より少しだけ狭い溝であったことは事実でしょうが。しかし、回転速度も目新しいものではありませんでした。33 1/3回転というのは、ラジオ局のトランスクリプション盤における標準でしたし、さらに昔の Vitaphone 盤でも使われていたものです。ですから、速度について新規性はありませんでした。再生針も当時の Victor の78回転盤と同仕様でした。

Thanks for clarifying that. Occasionally, there are still some rumblings that the Columbia LP was sort of “inspired,” for the lack of a better word, by the Victor long-playing discs of 1932 (NOTE: meaning “Program Transcription” records).

明確な回答、ありがとうございます。いえ、Columbia の LP は、1932年の RCA Victor による長時間レコード(訳註: Program Transcription 盤のこと)に、言葉は悪いが、ある意味で「インスパイア」されたのだ、という噂をいまだに時折耳にするもので。

Those Victors were already a stale joke in the industry, so we would have been wasting our time if we had started by going back to them. But I will admit that we did pay a lot of attention to an earlier long-playing record, the one that Edison had developed in the mid-1920s. Do you know about those Edisons?

あの Victor の長時間レコードは、業界ではすでに陳腐なジョークになっていましたから、そこに戻るところから(Columbia での LP 開発を)始めたのでは、時間の無駄になってしまうでしょう。しかし我々は、1920年代半ばにエジソンが開発した長時間レコードにかなり注目したのは事実です。そのエジソンの長時間レコードのことをご存知ですか?

Yes, but I’ve never actually seen or heard one.

ええ、しかし、実物を見たことも、実際に音を聴いたこともないんです。

Let me tell you, those records were a masterpiece of engineering. And not just in the lab, but in their commercial form. I got two of those thick, long-playing discs from a friend of mine who collected old records. They were vertical-cut records, like everything Edison put out. And they were recorded acoustically, not electrically. The groove specs were almost unbelievable when we put them under a microscope and had them measured. Now remember, we were cutting the LP with a 1/200-inch groove. But Edison had cut his with a 1/450-inch groove!

言っておきますが、あのレコードは工学による大傑作でした。しかも研究室内に閉じたものではなく、実際に市販されていたものでした。古いレコードを蒐集している友人から、あの分厚い長時間レコード盤を2枚譲ってもらったのです。他のエジソン盤と同様に、縦振動記録のレコードでした。しかも電気録音ではなく、アコースティック録音でした。その盤を顕微鏡にセットし、溝を測定してみると、ほとんど信じられないような仕様になっていました。覚えてますか、我々の LP では、1/200 インチの幅で溝をカットしていたんです。しかし、エジソンの長時間レコードはというと、なんと 1/450 インチ幅の溝が刻まれていたんです!

“The James A. Drake Interviews: William S. Bachman on the Development of the Columbia LP”Edison Long-Playing Record については、DHAR (Discography of American Historical Recordings) の 特集記事 に詳しいです。

For your information, DHAR (Discography of American Historical Recordings) has a dedicated article of Edison Long-Playing Record.

また、YouTube 上には、Edison Diamond Long Playing レコードを再生する動画がいくつかアップロードされています。

Also, there are several YouTube videos, featuring the reproduction of Edison Diamong Long Playing records.

source: screenshot from “Edison Long Play 10006 (the good one) Both Sides — 24 minutes”, Don Wilson.

And they played at the standard 78 speed, isn’t that correct?

で、その盤は、標準的な78回転で再生されていた、というので合ってますか?

Well, if I remember rightly, Edison used 80 r.p.m. as the standard speed for those old Diamond Discs. And he didn’t vary the speed like Victor used to do in the acoustical days. There’s a lady [Aida Favia-Artsay] who has done a study of all of the Caruso records that he made at Victor. The recording speeds that they were using could vary as much as five r.p.m. from one session to the next.

えっと、私の記憶が確かならば、エジソンはこの古いダイヤモンドディスク用の標準速度として 80rpm を使用していたはずです。そして、アコースティック録音時代の Victor がやっていたような、回転速度を変化させるなんてことはしていませんでした。Victor に録音されたカルーソの全録音を全て調査した女性(Aida Favia-Artsay) がいるのですが、(彼女の研究によると)記録時の回転速度は録音セッションごとに 5rpm も異なっていたのです。

Yes, I know her, and know her book. She even included a stroboscope disc with the book so that listeners could check the turntable speeds for themselves, and hear Caruso at score pitch.

ええ、彼女のことも、彼女が書いた本のことも、知っています。その本にはストロボスコープディスクが付属していて、カルーソの録音を正しいピッチで聴けるようにと、リスナーがターンテーブルの速度を自分で調整できるようにしていたんですよね。

“The James A. Drake Interviews: William S. Bachman on the Development of the Columbia LP”Bachman 氏が根っからのエンジニアであり、過去の技術開発の歴史を調べ尽くした上で、Columbia LP 開発に挑み、多くの技術を作り出していったことがよくわかるエピソードです。

The above episode surely represents that Mr. Bachman fundamentally was an engineer, and he researched and studied old technologies and their history, then tried the Columbia LP development (and he actually invented some of the important technology).

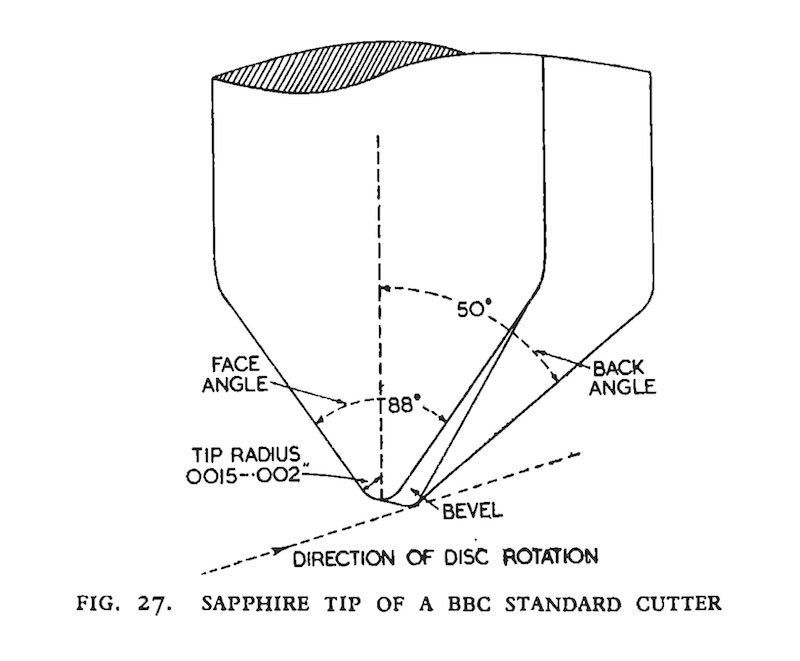

続いて、ラッカー原盤にカッティングする際の重要な構成部品、カッティングスタイラス(カッター針)に関する重要な技術について、再びエジソンの先見性について語られるくだりです。

Then he continues to stress the greatness of Edison and his foresight, by discussing the cutting stylus (which is one of the most important parts when cutting the sound onto the lacquer discs).

Back to Edison, do you know that the stylus he developed for those records, his diamond stylus, was elliptical, not round?

エジソンの話に戻りますが、(Edison Diamond Disc 用に)彼が開発した針、ダイヤモンドスタイラスは、丸型ではなく楕円形だったことをご存知ですか?

Did he file a patent on that?

エジソンはそれを特許にしていたのですか?

No, but it’s there in his notebooks at West Orange. And each side of those Edisons, by the way, played for twenty-five minutes. At 80 r.p.m.! Can you imagine that? How the “Old Man,” as his staff always called him, could make recording lathes that would consistently cut 1/450-inch grooves is still amazing to me. That’s one of the truly great engineering feats in the history of this industry. But, of course, Edison had invented the phonograph, so I guess anything he did was bound to be the best.

いえ、でもウエストオレンジにある彼のノートにしっかり記録されているんです。ところで、その Edison Diamond Disc 長時間レコードは、片面で25分間再生可能だったんです。しかも 80rpm で、ですよ! 想像できます? 彼の(ウエストオレンジ研究所の)スタッフがいつも「親方」(Old Man)と呼んでいた、その人が、どうやって 1/450 インチの溝をコンスタントに刻むカッティングレースを作ったのか、私にとってそれは今でも驚きです。この業界における、歴史上本当に偉大な技術的偉業の1つと言えるでしょう。ですが、もちろん、エジソンは蓄音機を発明した人なのですから、何をやっても1番になるに決まってる、ってことでしょうね。

Did you ever know anyone who worked directly with Edison in the 1920s?

1920年代にエジソンと直接仕事をしていた方をどなたかご存知ないでしょうか?

No. But I certainly read all of the patents he filed about recording technology. Do you know that he didn’t file a patent for one of the most important cutting styluses that he designed?

いいえ。しかし私は、彼(Edison)が取得した録音技術に関する特許文書を全て読み込みました。彼が設計した、カッティングスタイラスに関する最も重要な設計のひとつが、特許申請されていないのをご存知ですか?

I don’t think I’m familiar with that. What was its design?

それは分からないです。その設計とはなんだったのですか?

It was a heated cutting stylus. It had a heating coil on it.

カッター針を温める設計です。針には電熱線が巻き付けられていたのです。

But don’t you hold the patent for the heated-coil stylus?

しかし、その「heated-coil stylus」はあなたが特許を取得しているんじゃありませんでしたか?

Yes, I do. And I wouldn’t have that patent if Edison had ever filed one. He had been using a heated cutting stylus before World War One. I guess he thought it was so obvious that a heated stylus would cut a much better groove in a warm wax [recording] blank that he didn’t give any thought to patenting it. But the heating-coil stylus is right there in his lab books at West Orange.

ええ。エジソンが特許申請していたら、私が取得することはなかったでしょう。エジソンはこの技術を第一次世界大戦前から使っていたのです。きっとエジソンは、温めたワックスマスター盤に、電熱線で温めたスタイラスでカッティングするとより精緻な溝が刻めるなんて、当たり前すぎることだと考えていたのではないでしょうか。しかし、そのことが間違いなく、ウエストオレンジの彼の研究所のノートに書かれているのです。

“The James A. Drake Interviews: William S. Bachman on the Development of the Columbia LP”のちほど セクション12.2.1 で触れる、Columbia LP 誕生に欠かせなかった、Bachman 氏によるカッター針の技術革新のインスピレーションの源泉(あるいは「元ネタ」)は、1920年代中頃のエジソンに由来していた、というのです。

So Mr. Bachman emphasize that his innovation and invention of cutting stylus (as we see later in Section 12.2.1) was accomplished, as he was inspired by (or originated from) Edison’s extraordinary technology in the mid-1920s.

上の1977年インタビューでは、Bachman 氏は “Heated-coil stylus” つまりカッター針を電熱線で温める技術を特許にしている、と述べていますが、いくら検索しても該当する特許が見つかりませんでした。

In the 1977 interview shown above, Mr. Bachman recalls he holds the patent for the “heated-coil stylus”. However, although I desparately tried identifying the particular patent document, I could not find the patent itself.

そんな時たまたま、Bachman 氏が執筆し AES ジャーナル(論文誌)1977年10/11月号に掲載された「The LP and the Single」という論文(というより解説記事?)を目にし、以下のような記載があるのを発見しました。

Then coincidentally I found the paper (or technical article) written by Mr. Bachman himself, published on the Oct-Nov 1977 issue of the Journal of the AES: “The LP and the Single”. In the article, I found the following paragraph:

The problem was solved by winding a fine wire around the stylus near the tip and heating it with a direct current to equalize this differential. A patent was never applied for on this invention because of timidity or lack of zeal on the part of the attorneys. Columbia enjoyed its use as a trade secret for about a year, It inevitably leaked and was therefore made the subject of a paper to establish Columbia as its originator.

そこで、(録音・カッティング用の)スタイラスの先端付近に細いワイヤーを巻きつけ、直流で加熱して、(カッティングした溝の形成が)均等になるようにすることで、問題が解決された。この発明は、弁護士たちの気の迷いか、熱意のなさか、ともあれ特許出願されることはなかった。Columbia はこの発明を企業秘密として約1年間使用し、(他社に対する優位性を)大いに楽しんでいた。しかし企業秘密はどうやっても漏れてしまうものなので、Columbia が発案者であることを証明するために、これを題材とした論文を発表した。

“The LP and the Single”, William S. Bachman, Journal of The Audio Engineering Society, Vol.25, No.10/11, Oct./Nov. 1978, pp.821-82312.2 Technological Background of Long Playing Microgroove records

では、ここからは、Columbia LP の技術的側面について、さまざまな論文や記事をみていきましょう。

Now let’s move on to the technical aspects of the Columbia Long Playing Microgroove records. We’re going to read several papers and articles.

12.2.1 “The Columbia Hot Stylus Recording Technique” (1950)

上の セクション12.1.4 のコラム で紹介した「Columbia が発案者であることを証明するために、これを題材とした論文を発表した」という、その論文がこちらです。タイトルは「The Columbia Hot Stylus Recording Technique」、Audio Engineering 誌1950年6月号 に掲載されました。著者は Bachman 氏ご本人です。

“It inevitably leaked and was therefore made the subject of a paper to establish Columbia as its originator” — as we read in the above column of Section 12.1.4. So here is the paper, entitled “The Columbia Hot Stylus Recording Technique” — published in the June 1950 issue of Audio Engineering Magazine. The auther is Mr. Bachman himself.

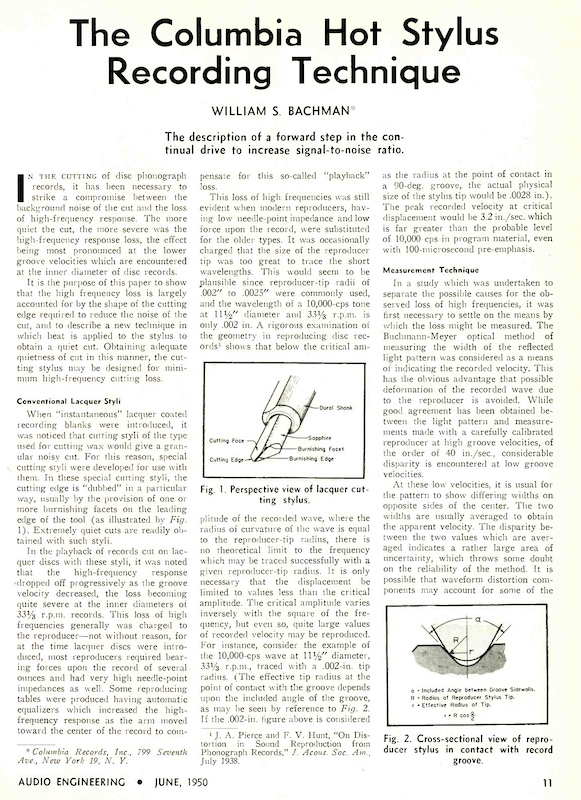

source: Audio Engineering, Vol.34, No.6, June 1950, p.11.

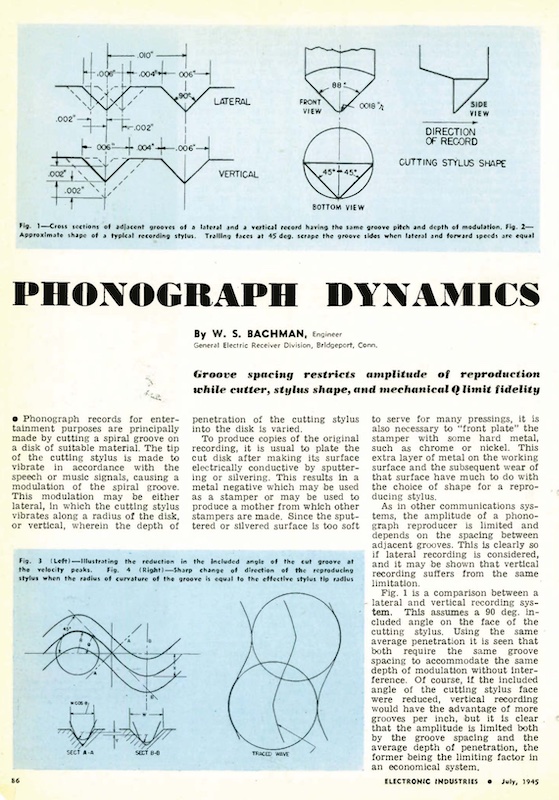

さて、Bachman 氏のこの論文は、タイトルの通り、カッティングスタイラス(カッター針)を熱した状態でカッティングする新技術の紹介なのですが、それ以上に、カッティング時のノイズと高域減衰の関係について丁寧に解説された記事でもあります。冒頭はこう始まります。

This Bachman’s paper, as the title says, describes his new technology of “heated stylus”. Furthermore, this paper is a great summary of the relationship between background noise and high-frequency response during the cutting of disc records. The beginning of his paper reads like this:

IN THE CUTTING of disc phonograph records, it has been necessary to strike a compromise between the background noise of the cut and the loss of high-frequency response. The more quiet the cut, the more severe was the high-frequency response loss, the effect being most pronounced at the lower groove velocities which are encountered at the inner diameter of disc records.

ディスクレコードのカッティングにおいては、カッティング時のバックグラウンドノイズと、高周波帯域レスポンスの損失との間での妥協が必要とされてきた。カッティングが静かであればあるほど、高域のレスポンスが失われ、その影響はディスクレコードの最内周、すなわち最も線速度が低い領域で顕著に現れる。

It is the purpose of this paper to show that the high frequency loss is largely accounted for by the shape of the cutting edge required to reduce the noise of the cut, and to describe a new technique in which heat is applied to the stylus to obtain a quiet cut. Obtaining adequate quietness of cut in this manner, the cutting stylus may be designed for minimum high-frequency cutting loss.

本論文の目的は、(ディスクカッティング時の)高周波帯域の損失が、カッティング時のノイズを減らすために必要なカッター針の刃先の形状に大きく左右されることを示し、同時に、カッター針に熱を加えながら低ノイズのカッティングを行う新しい技術を説明することである。この方法で十分に静粛なカッティングが行えることにより、カッティング時の高周波帯域損失を最小限に行えるよう、カッター針の刃先形状を設計可能となる。

“The Columbia Hot Stylus Recording Technique”, William S. Bachman, Audio Engineering, Vol.34, No.6, June 1950, pp.1-3そして本論文は「Conventional Lacquer Styli」(従来のラッカー針)というセクションに入り、従来のワックス盤カッティングとラッカー盤カッティングの違い、そして両者のカッター針の形状の違いについて説明が行われます。ちょうど本稿 Pt.6 セクション6.1 で学んだ辺りに関係する話です。

Then the paper proceeds to the section entitled “Conventional Lacquer Styli”, which describes the difference between the stylus for wax discs and the stylus for lacquer discs — somewhat related to the things I previously learned in the Pt. 6 Section 6.1.

Conventional Lacquer Styli

従来のラッカー針

When “instantaneous” lacquer coated recording blanks were introduced, it was noticed that cutting styli of the type used for cutting wax would give a granular noisy cut. For this reason, special cutting styli were developed for used with them. In these special cutting styli, the cutting edge is “dubbed” in a particular way, usually by the provision of one or more burnishing facets on the leading edge of the tool (as illustrated by Fig.1). Extremely quiet cuts were readily obtained with such styli.

「即時録音」用ラッカー盤が登場した際、ワックス盤用カッター針でラッカー盤をカッティングすると、ザラザラとしたノイズの多いカッティングとなることが判明した。このため、ラッカー盤カッティング用に特別なカッター針が開発された。これら特殊カッター針では、針のエッジが特殊な方法で「平らに」されており、通常は針の前面の縁に1つ以上のバニシングファセットが設けられている(図1を参照)。このような針を用いると、極めて静粛なカッティングが容易に行える。

In the playback of records cut on lacquer discs with these styli, it was noted that the high-frequency response dropped off progressively as the groove velocity decreased, the loss becoming quite severe at the inner diameters of 33 1/3 r.p.m. records. This loss of high frequencies generally was charged to the reproducer — not without reason, for at the time lacquer discs were introduced, most reproducers required bearing forces upon the record of several ounces and had very high needle-point impedances as well. Some reproducing tables were produced having automatic equalizers which increased the high-frequency response as the arm moved toward the center of the record to compensate for this so-called “playback” loss.

この特殊カッター針でカットされたラッカー盤を再生すると、溝速度の低下とともに高域レスポンスが徐々に低下し、33 1/3回転のレコードの最内周でその損失が深刻なものとなることが指摘された。この高域レスポンス低下は概して再生機器側の問題とされてきた。とはいえ理由がないわけではなく、ラッカー盤が登場した頃の再生機器はまだ、針圧が数オンスに達するもので、針先のインピーダンスも非常に高かったからである。当時の再生用ターンテーブルには、「再生時の損失」を補正するという名目でアームが内周側に動くのにあわせて高域レスポンスを補正するような自動イコライザを装備しているものもあった。

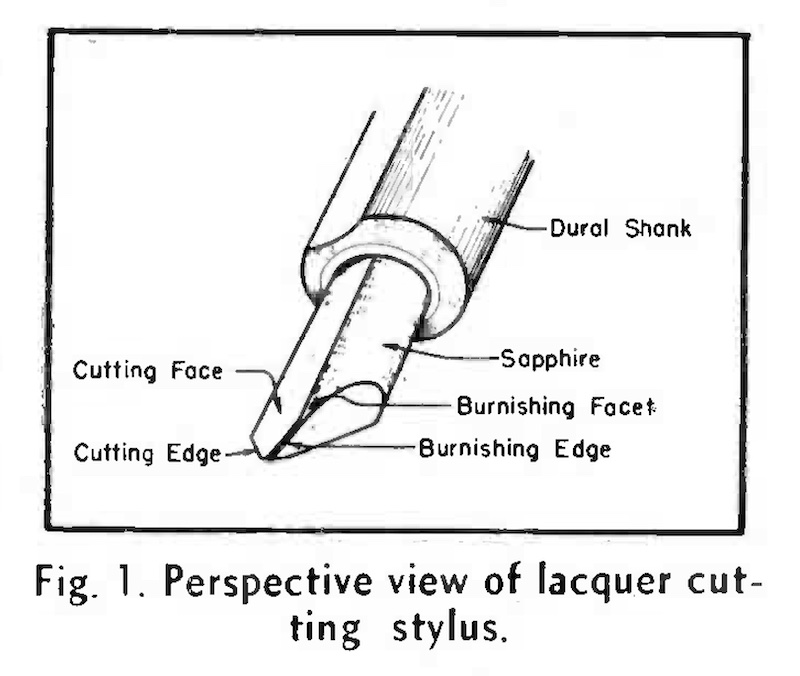

“The Columbia Hot Stylus Recording Technique”, William S. Bachman, Audio Engineering, Vol.34, No.6, June 1950, pp.1-3本論に入る前に、上の引用中「バニシングファセット」 (Burnishing Facet) という聞き慣れない用語がでてきました。コトバだけの説明ではどうにもわかりにくくなるので、各種論文や書籍からイラストを借りてみます。

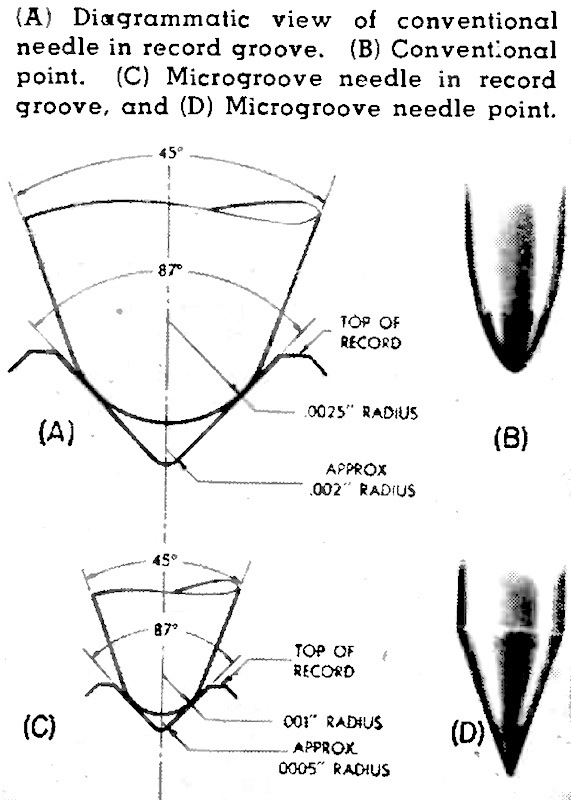

The term “Burnishing facet” is rather new to me. So I will look into some other papers and articles (with enlarged illustration of cutting styli) to understand what it is, before proceeding to the main topic.

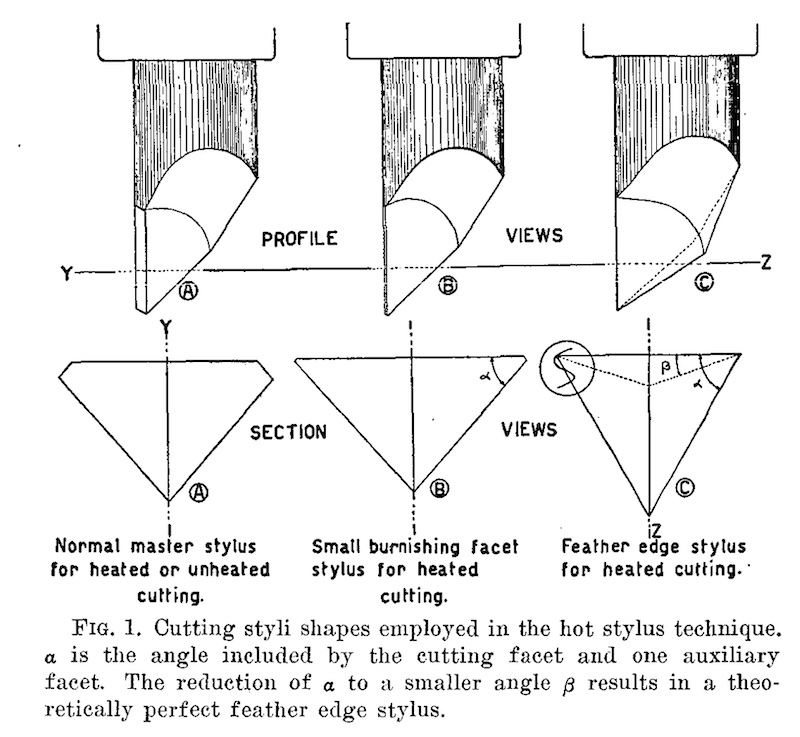

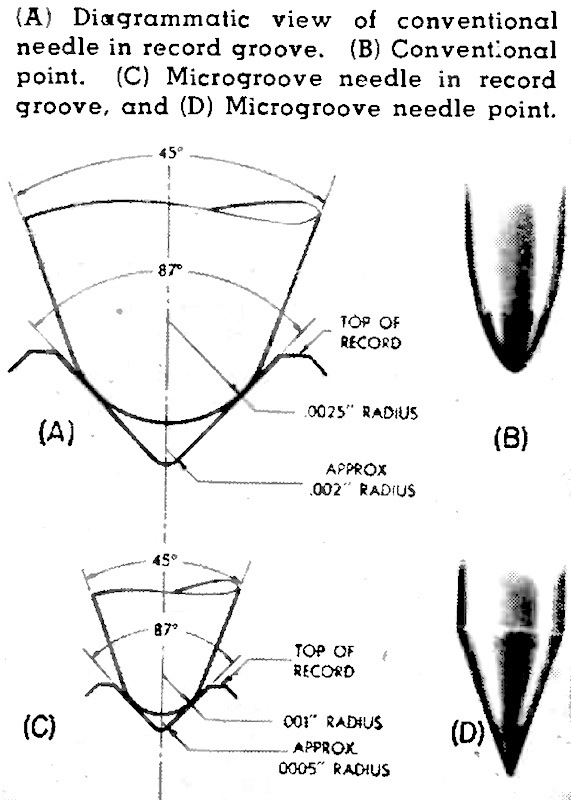

下は Bachman 氏の論文 (1950) に掲載された図1ですが、確かにカッター針は再生針と全く違う形状をしています。「Cutting Face」と書かれたフラットな面が、カッティング時の正面を向き、「Cutting Edge」が、刻まれる溝の断面形状を規定します。フラットな面の進行方向反対側は2つの広い面(名前なし)で構成されており、さらに「Cutting Face」と裏面との間のエッジ、つまり「Cutting Edge」と「Burnishing Edge」の間には、ほんの少しの幅だけ面が作られており、この図では「Burnishing Facet」と書かれています。

The below Figure 1 is from the Bachman’s paper (1950). The cutting stylus actually have a completely different shape from that of reproducing stylus. The frontmost flat facet is named “Cutting Face”; and the “Cutting Edge” regulates the shape of the groove on the disc; the back side consists of two flat facets (unnamed here); and the area between “Cutting Face” and backside facets is polished (or “dulled”) to create a narrow facet, named “Burnishing Facet” here.

source: Audio Engineering, Vol.34, No.6, June 1950, p.11.

一方、Read 氏執筆の書籍 “The Recording and Reproduction of Sound” (1952) のカッター針に関する章では、「Cutting Face」は同じですが、裏の2面は「Clearance Face」とされ、またエッジに作られた面は同じく「Burnishing Facet」と名付けられています。

On the other hand, in “The Recording and Reproduction of Sound” (1952) by Oliver Read, the front facet has the same name; “Cutting Face”; back facets named “Clearance Face”; the edge named “Burnishing Facet”, same as in Bachman’s paper.

source: “The Recording and Reproduction of Sound”, Oliver Read, 2nd Edition, 1952, p.114

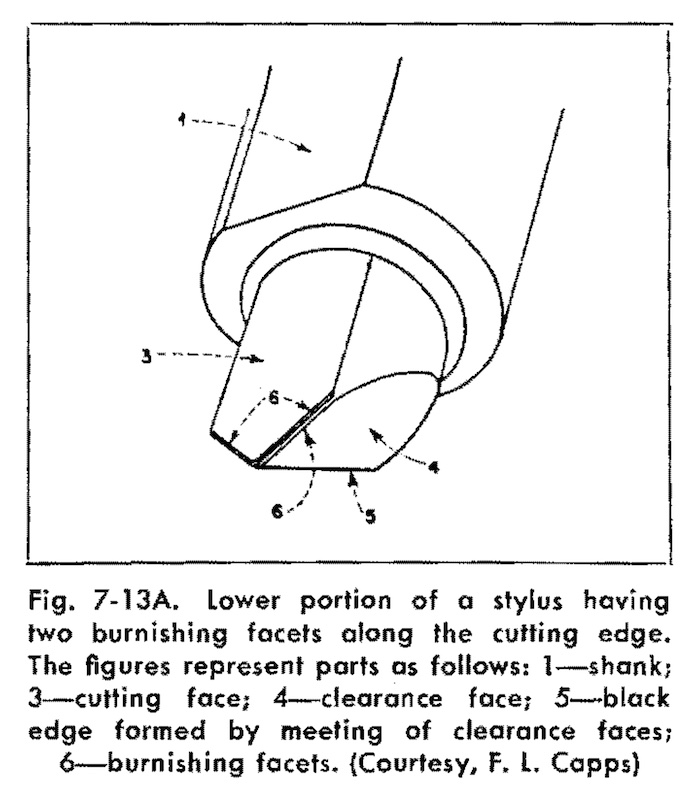

さらに、“BBC Recording Training Manual” (1950) の第2章 “Principles of Disk Recording” においては、米国と英国の違いらしく、正面が「Face」、背面が「Back」、エッジ面は「Bevel」とされています。

Another example follows. in Chapter 2 “Principles of Disk Recording” of the book “BBC Recording Training Manual” (1950), the names may reflect the difference of British terms and American terms — front facet as “Face”; back facets as “Back”; and dulled edges as “Bevel”.

source: “BBC Recording Training Manual”, 1953, p.40.

1956年AES年次総会で口頭発表され、のちにジャーナル誌に掲載された、ブラジルRGEレーベルのエンジニア Carlos E.R. de A. Moura 氏による “Practical Aspects of Hot Stylus” では、正面が「Cutting Facet」、背面が「Auxilary Facet」、エッジ面が「Burnishing Facet」となっています。

Yet another example here — “Practical Aspects of Hot Stylus” (1957) by Carlos E.R. de A. Moura (from Brazilian RGE label), originally presented at the AES Annual Meeting in 1956, describes the front facet as “Cutting Facet”; back facets as “Auxilary Facet”; and the edge as “Burnishing Facet”.

source: “Practical Aspects of Hot Stylus”, Journal of Audio Engineering Society, Vol.5, Issue 2, April 1957, pp.90-93.

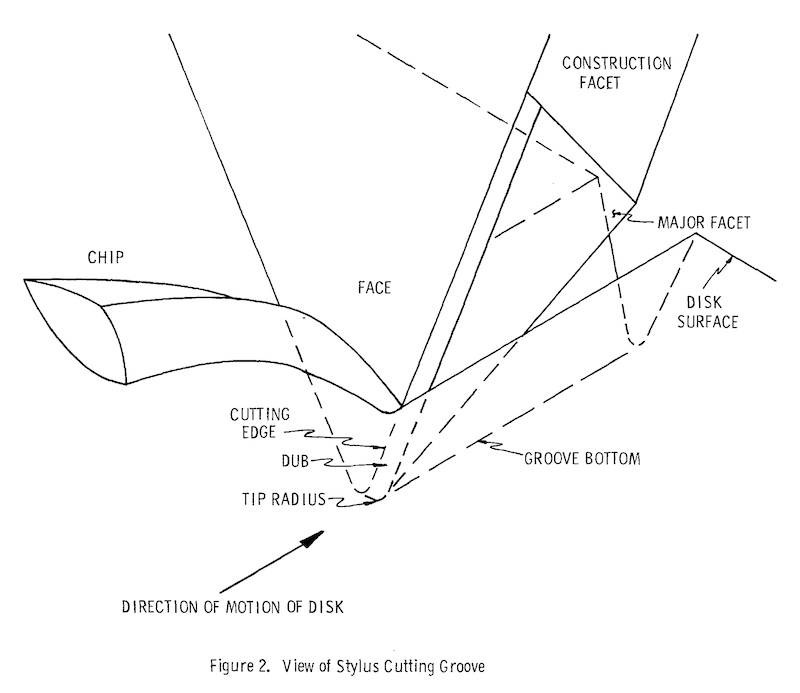

さらに次はもう1つ別の例で、CBS 研究所のエンジニア3名によって、1963年の AES 年次総会における口頭発表 “The Saga of The Recording Stylus”(録音針の年代記)のプレゼン資料のイラストは、カッティング針の形状と、カッティングされるラッカー盤の位置関係や回転方向が分かりやすいのですが、ここでもまた各部の名称が異なっています。正面が「Face」、背面が「Major Facet」、そしてエッジの面が「Dub」となっています。

One more example — “The Saga of The Recording Stylus” by three CBS Labs engineers, presented at the AES Annual Meeting in 1963, denotes as: “Face”, “Major Facet”, and “Dub”, respectively.

source: “The Saga of the Recording Stylus”, Schwartz, Gust and Bauer, AES Convention 15 (October 1963).

これらの呼称のゆらぎをまとめると、こうなりますでしょうか。

Let’s summarize the fluctuation of these notations:

| 正面 front surface |

背側面 back surfaces |

エッジ面 dulled edge surface |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Bachman (1950) |

cutting face | — | burnishing facet |

| Read (1952) |

cutting face | clearance facets | burnishing facet |

| BBC (1950) |

face (cutting face) |

back (clearance faces) |

bevel (burnishing facets) |

| Moura (1957) |

cutting facet | auxilary facets | burnishing facet |

| Schwartz et al (1962) |

face | major facet | dub |

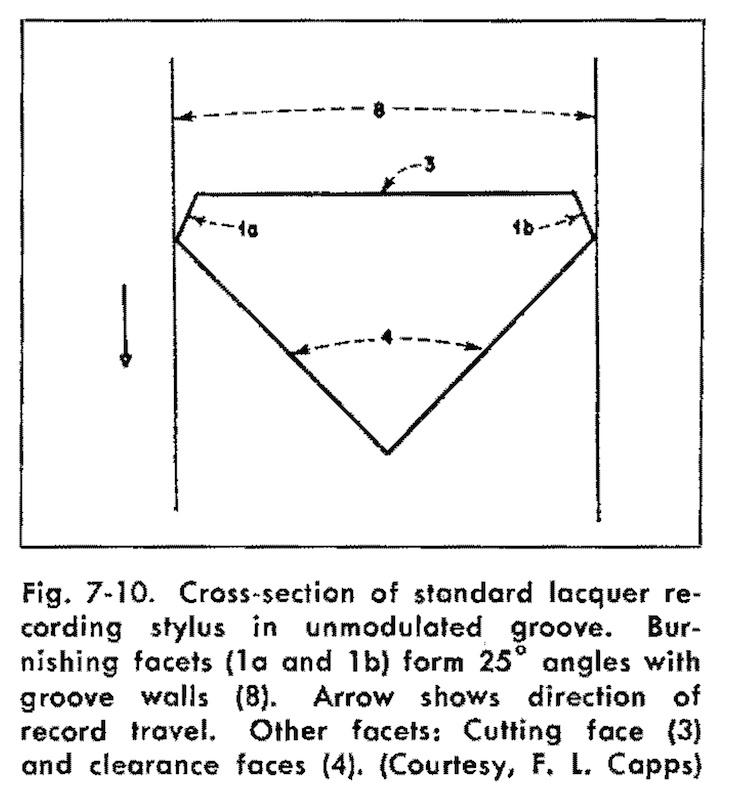

ということで、カッター針をラッカー盤に対して上から覗いた際の断面は、下図のようになります。図の上が、これからカットする方で、矢印方向(上から下)が、ラッカー盤の回転方向です。

Anyway, cross-sectional view of lacquer recording stylus in unmodulated groove would be like the below illustration. The arrow on the left side (up to down) shows the direction of record travel.

source: “The Recording and Reproduction of Sound”, Oliver Read, 2nd Edition, 1952, p.113

ともあれ、こういうことです。かつてワックス盤にカッティングを行っていた時代は、原盤が非常に柔らかいため、カッター針の角は鋭利なままだったが、ラッカー盤になってからは、そのままカッティングするとS/N比が悪い溝しか刻めないことが判明し、「Dub」「Bevel」「Burnishing Facet」などと呼ばれる、角に作った面(上の図でいうと 1a と 1b)を設けて対応した。

So let’s get back to the main point. The thing is: back when wax discs were used, the disc was so soft enough that a cutting stylus with a sharp edge could cut the groove excellently; but after the introduction of lacquer-coated discs, it was found that such stylus could not cut the groove with low background noise; then the dulled edge called “Dub”, “Bevel”, “Burnishing Facet” or whatever, as we see 1a and 1b in the above illustration, was developed.

「Burnishing Facet」の幅を長くすればするほど、カッティング時のサーフェスノイズが減少する。ところが静かなカッティングができる代わりに、特に盤の内周に向かえば向かうほど、記録される溝から高周波域が失われてしまう。

The more width of the “Burnishing Facet”, the more contribution for the quiet cut onto the lacquer discs. However on the other hand, the high-frequency response loss greatly increases, as the groove diameter decreases.

逆に、高周波域までカッティングしようとして、「Burnishing Facet」の幅を狭くすれば、今度はカッティング時のサーフェスノイズが増大してしまう。

Conversely, if the width of the “Burnishing Facet” was modified narrower, in order to reduce high-frequency loss, background noise (or surface noise) would greatly increase.

ここで解説されている内容については、先行研究があります。Audio Devices 社の副社長 C.J. LeBel 氏が、1941年10月、ASA (Acoustical Society of America, アメリカ音響学会) の第26回年次総会で口頭発表し、1942年1月号にASA論文誌に掲載された「Properties of the Dulled Lacquer Cutting Stylus」という論文です。これが、カッター針の形状と、ノイズや高周波帯域減衰との関係を科学的・学術的に示した、最初の研究成果です。

This discussion of “high-frequency loess” vs “background noise” was originally authored by C.J. LeBel, Vice President of Audio Devices, presented at the 26th Annual Meeting of ASA (Acoustical Society of America) in October 1941, then published on the Jan. 1942 issue of the Journal of ASA, entitled “Properties of the Dulled Lacquer Cutting Stylus”. This was the first research work clarifying the relationship among the cutter stylus shape, background noise, and high-frequency loss.

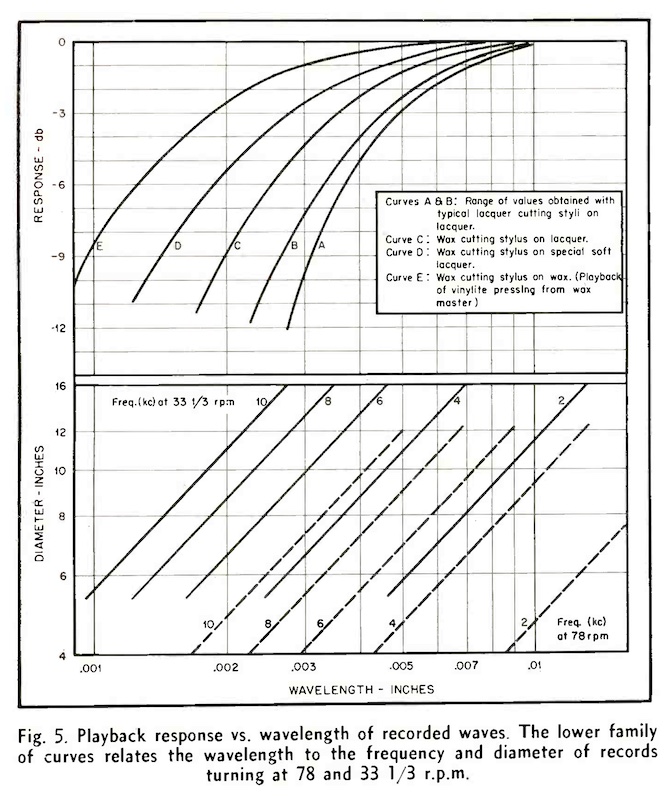

通常のラッカー盤、特製の柔らかいラッカー盤、そしてかつて使われていたワックス盤、など、さまざまな原盤にカッティングを行った結果、カッター針の形状と原盤のカッティングしやすさが、高域まで記録できるかどうかの重要なファクターであることが確認された。

So Mr. Bachman tried cutting with various recording discs — regular lacquer-coated discs, special soft lacquer discs, and traditional wax discs — with various cutter styli with different shapes. Then he found that both the shapes of styli and the ease of disc cutting might be important facters for excellent cutting without high-frequency loss.

そこで Bachman 氏は、「Burnishing Facet」の幅が広いと静粛なカッティングができるのは、カッティング時に「Burnishing Facet」がラッカーを削りとる際に生じる摩擦熱によるのではないか、と考えた。

And Mr. Bachman set up a hypothesis — the fact that wider “Burnishing Facet” results in quiet cutting could be the result of the heat produced by the Burnishing Facet on the recording styli, while cutting.

source: Audio Engineering, Vol.34, No.6, June 1950, p.13.

さまざまな原盤、2種類のカッター針により、高域記録特性を計測しプロットしたグラフ

そして Bachman 氏が実現したのが、摩擦熱の代わりに(実はエジソンがかつてやっていた)カッター針を電熱線で温める技術で、「Burnishing Facet」の幅を狭くしたまま、すなわち高周波帯域の記録特性をキープしたまま、サーフェスノイズを減らす、というものです。

With this hypothesis, Mr. Bachman decided to emply “Heated Stylus” technique (the idea originally derived from Thomas Edison’s laboratory books, though): heating the recording stylus with coil of copper wire, keeping the burnishing facet width very narrow — thus keeping high-frequency response even in the inner diameter — at the same time enabling to reduce background (surface) noise.

Heated Stylus Performance

カッター針に熱を与えた場合のパフォーマンス

On the theory that the burnishing facets on the recording styli were producing heat through friction to “flow” a smooth surface on the cut groove, it was proposed that the stylus be heated by other means. The first method tried, in early 1948, consisting of winding a small coil of copper wire directly on the sapphire jewel and heating it with a direct current, worked so well that it is still in use, although many other means have been considered. The effect of this heat on the reduction of the groove noise was so pronounced that it immediately became apprant that much smaller, or possibly negligbly small, burnishing facets could be used. This also was found to be true, the styli with small facets requiring more heat to get rougly the same background noise.

録音用カッター針の「Burnishing Facet」が摩擦によって熱を発生させ、カットされる溝の表面を滑らかにする、という理論から、カッター針を他の手段で加熱することが提案された。1948年初頭、サファイア製のカッター針に直接銅線を巻いて小さなコイル状にし、直流で加熱する方法を最初に試みたところ、非常にうまくいったので、現在でもその方法が使用されている。この加熱による溝ノイズ低減効果は非常に顕著であり、「Burnishing Facet」をもっと小さく、あるいは無視可能なレベルにまで小さくできることが分かった。また、「Burnishing Facet」が小さいまま、バックグラウンドノイズを低くするには、より多くの熱が必要であることも判明した。

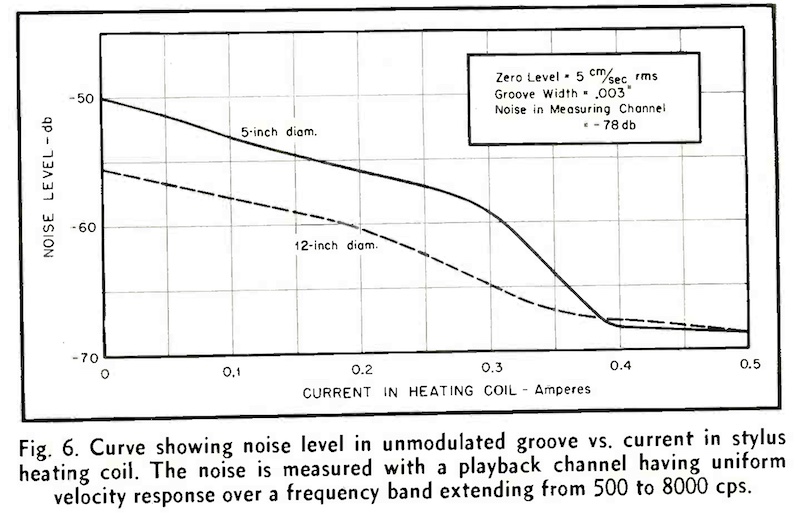

Figure 6 is a plot of the noise of a cut made with a sharp edge cutting stylus with varying heating currents applied. The noise was measured on a velocity basis over a band extending from 500 to 8000 cps. The 500-cps limit was chosen to eliminate hum and rumble vibration from the measurement, and the 8000-cps upper limit was chosen to avoid response in the region where the dynamic mass of the reproducer at the stylus tip might resonate with the compliance of the groove which it engages. Since these measurements were made on a velocity vasis, it is evident that a further reduction in the measured noise would be obtained with roll off of the high frequencies, such as that used to equalize for pre-emphasis in recording. Even so, reduction of as much as 18 db in the background noise are readily effected, giving a resulting noise level 68 db below the NAB standrad recorded probram level.

図6は、角が鋭利な状態のカッター針に、加える電流を変化させながらカッティングを行った際のノイズをプロットしたものである。ノイズは、500Hz〜8,000Hzの周波数帯域で、速度ベースで測定された。測定下限を 500Hz としたのは、ハムやランブルノイズを測定から排除するためであり、上限を 8,000Hz としたのは、再生スタイラスにおける再生機(トーンアーム+カートリッジ)の動質量により、トレースする溝のコンプライアンスと共振する領域の応答を避けるためである。この測定はベロシティベース(速度ベース)で行われたので、録音時のプリエンファシスに対応するイコライズ(デエンファシス)を施せば、さらに測定ノイズが減少することは明らかである。それでも、バックグラウンドノイズの18dBもの低減が容易に実現でき、結果として NAB 規格の標準録音レベルを68dBも下回るノイズレベルという結果が得られた。

“The Columbia Hot Stylus Recording Technique”, William S. Bachman, Audio Engineering, Vol.34, No.6, June 1950, pp.1-3

source: Audio Engineering, Vol.34, No.6, June 1950, p.14.

無音でカッティングした際、カッター針にかける電流と得られるノイズレベルをプロットしたもの。12インチ盤の最外周と最内周でカッティングした結果の比較。

いずれの場合でも、十分に電流をかけた場合、サーフェスノイズは非常に低くおさえられることが確認された(グラフの右端)。

話を戻すと、カッター針を電熱線で加熱することにより、「Burnishing Facet」を狭くしたまま、溝がよりスムーズにカッティングでき、結果として無音時のサーフェスノイズの減少に成功した。同時に「Burnishing Facet」が狭いままであることで、線速度が遅い領域でも、より高周波帯域まで溝に記録可能になった、ということです。

To summarize, by heating the recording stylus by coil with direct current, smoother cutting is possible while keeping the burnishing facet width narrow; and as a result, quiet cutting can be obtained. Also at the same time, burnishing facet width being narrow enough, high-frequency loss can be minimized even if the groove velocity decreases.

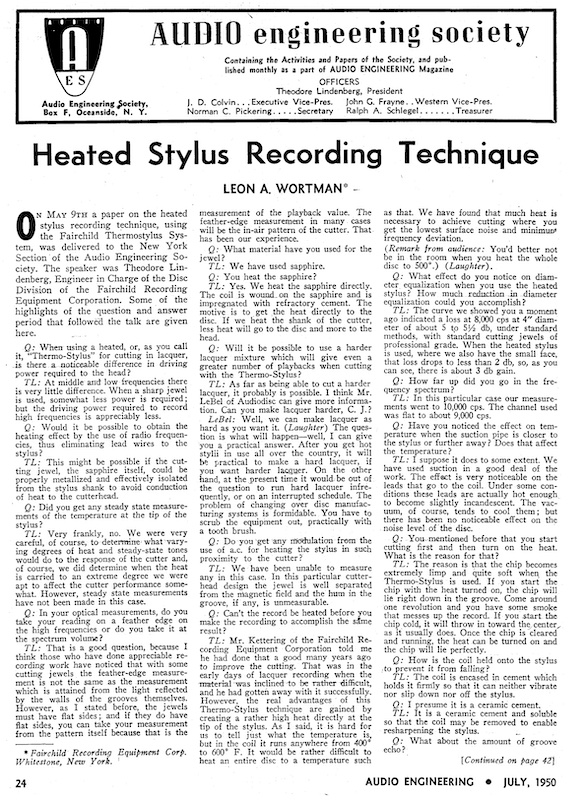

実は、Bachman 氏の論文が掲載された翌月、同じく Audio Engineering 誌の 1950年7月号、AES学会セクションに、Fairchild 社の Leon A. Wortman 氏が「Heated Stylus Recording Technique」というレポートを執筆しています。「Fairchild Thermo-Stylus System」という名前で開発した技術の論文を、1950年5月9日に Fairchild 社の Theodore Lindenberg 氏が提出、この論文に対する質疑応答をまとめた記事です。

Interestingly enough, there is a report entitled “Heated Stylus Recording Technique”, written by Fairchild’s Leon A. Wortman. This report was published in the AES Journal Section of July 1950 issue, Audio Engineering magazine — the next issue of the same magazine that contains Mr. Bachman’s paper (June 1950). This report is a questions-and-answers for the paper “Fairchild Thermo-Stylus System”, authored by Fairchild’s Theodore Lindenberg, who submitted this paper on May 9, 1950.

もしかしたら、ですが、Columbia の企業秘密だった技術が漏れ、5月に Fairchild が類似のシステムの論文を提出したことを受け、Columbia が先に実現していたことを示すために、Bachman 氏が急遽6月号に論文を掲載した。。。のかもしれませんね。

So, it could be that, as Mr. Bachman stated, the trade secret (hot stylus technique) leaked somehow outside Columbia/CBS, some companies including Fairchild started implementing some similar technique, and tried to publish papers and articles. And Mr. Bachman noticed the leak — thus he published the “Hot Stylus Technique” paper in a hurry, to the June 1950 issue.

source: Audio Engineering, Vol.34, No.7, July 1950, p.24

なお、Bachman氏の論文が掲載された1950年6月号の目次ページにも、その Fairchild Thermo-Stylus Kit の広告が掲載されています。

And coincidentally (or intentionally?), Fairchild Thermo-Stylus Kit Ad is on the “Table of Contents” page of June 1950 issue of the Audio Engineering magazine, that has the Bachman’s “Hot Stylus” paper.

source: Audio Engineering, Vol.34, No.6, June 1950, p.3.

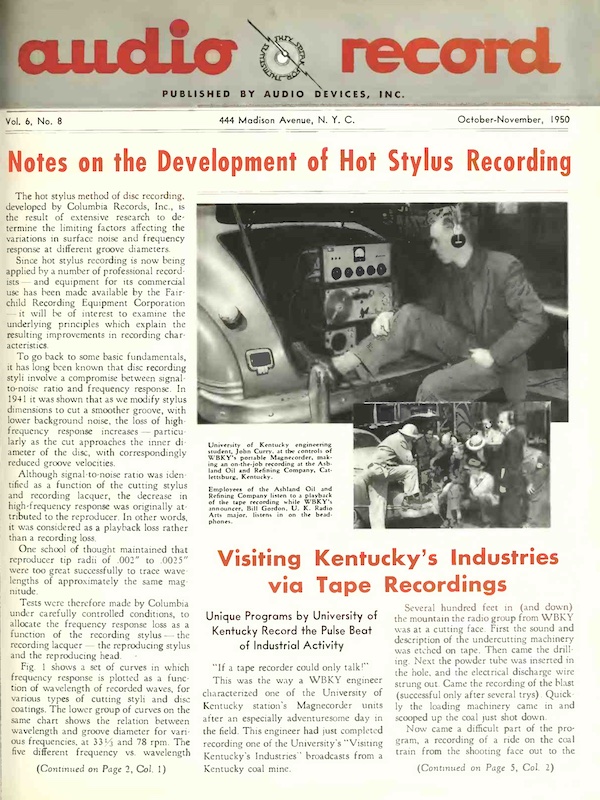

12.2.2 “Notes on the Development of Hot Stylus Recording” (1950)

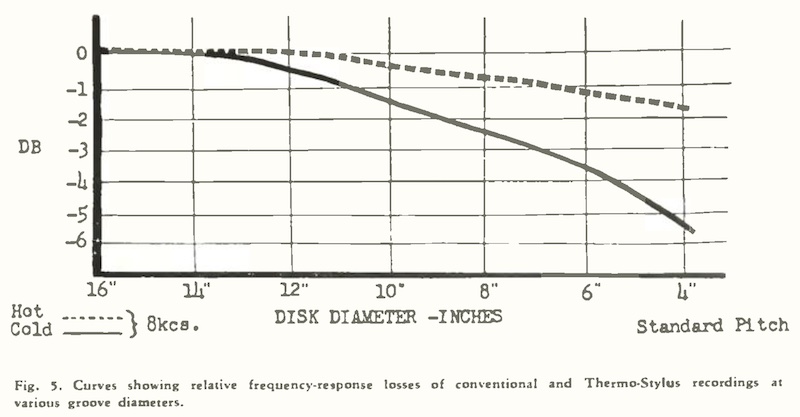

ラッカー盤や録音テープの製造主力メーカであった Audio Devices Inc. が1945年〜1959年に出版していた、Audio Record という販促用ブックレットの1950年10/11月号に、Bachman 氏の論文、および Fairchild 社の学会発表を受けた、秀逸なまとめ記事「Notes on the Development of Hot Stylus Recording」が掲載されているので、こちらも参照してみましょう。Bachman 氏の論文における、「高域減衰は再生側の問題だけではなく、録音側の問題でもある」と実験によって示す部分が、分かりやすく解説されています。

Audio Devices Inc., a maker of AudioDisks (lacquer discs) and AudioTape (reel-to-reel tapes), published its own promotional magazine called Audio Record, from 1945 to 1959. An excellent article entitled “Notes on the Development of Hot Stylus Recording” is the headline in the Oct/Nov 1950 issue of the Audio Record magazine. This article is an outstanding summary of the topic and its history, properly based on Bachman’s paper as well as Fairchild’s presentation — summarizing namely “high-frequency loss is due not only to reproducing equipments but also (or more likely) to recording instruments”.

source: Audio Record, Vol.6, No.8, October-November 1950, p.1

The hot stylus method of disc recording, developed by Columbia Records Inc., is the result of extensive research to determine the limiting factors affecting the variations in surface noise and frequency response at different groove diameters.

コロムビアレコードが開発した、ディスク録音における「ホットスタイラス」方式は、溝径の違いによるサーフェスノイズや周波数特性の変化に影響を与える制限要因を明らかにすべく研究を重ねた結果、生まれたものである。

Since hot stylus recording is now being applied by a number of professional recordists — and equipment for its commercial use has been made available by the Fairchild Recording Equipment Corporation — it will be of interest to examine the underlying principles which explain the resulting improvements in recording characteristics.

このホットスタイラス方式による録音は現在、フェアチャイルド社が製品化したことにより、プロフェッショナル分野において多くの録音エンジニア/録音スタジオですでに活用されている。ここで、(ホットスタイラス方式により)録音特性が向上したのは、どのような原理によるものなのか、検証してみるのも興味深いだろうと考える。

To go back to some basic fundamentals, it has long been know that disc recording styli involve a compromise between signal-to-noise ratio and frequency response. In 1941 it was shown that as we modify stylus dimensions to cut a smoother groove, with lower background noise, the loss of high frequency response increases — particularly as the cut approaches the inner diameter of the disc, with correspondingly reduced groove velocities.

基本的な話に立ち返ると、ディスク録音のカッター針は、S/N比と周波数特性の間で妥協が必要であることが古くから知られてきた。1941年、スタイラスの形状を変更してより滑らかな溝をカッティングすることで、バックグラウンドノイズを低減させると、高域特性の損失が増大することが示された。特に、カッティングが内周に近づき、それにともなって溝の線速度が低下する領域で(高域特性の損失が)顕著となる。

“Notes on the Development of Hot Stylus Recording”, Audio Record, Vol.34, No.6, June 1950, pp.1-3「1941年…示された」というのが、さきほどコラムで紹介した「Properties of the Dulled Lacquer Cutting Stylus」という論文で、1941年10月にアメリカ音響学会の年次総会で口頭発表され、1942年1月の論文誌に掲載された、Audio Devices 社の副社長 C.J. LeBel 氏の論文を指します。LeBel 氏は、Audio Record 誌で毎号解説記事を執筆しているので、この無記名記事自体も LeBel 氏によるものだったりするかもしれません。

The part “In 1941 it was shown that…” surely denotes the technical paper “Properties of the Dulled Lacquer Cutting Stylus”, authored by C.J. LeBel, Vice President of Audio Devices, Inc., presented at the 26th Annual Meeting of ASA (Acoustical Society of America) in October 1941, then published on the Jan. 1942 issue of the Journal of ASA. Mr. LeBel wrote technical columns under his own name, on almost all Audio Record issues, so this headline article (anonymous) could also be authored by Mr. LaBel.

Although signal-to-noise ratio was identified as a function of the cutting stylus and recording lacquer, the decrease in high-frequency response was originally attributed to the reproducer. In other words, it was considered as a playback loss rather than a recording loss.

このS/N比は、カッター針や録音用ラッカーによるものであると認識されたが、高域レスポンスの低下はもともと再生機器側に起因するものとされていた。つまり、録音ロスではなく、再生ロスとして考えられていたのである。

One school of thought maintained that reproducer tip radii of .002″ to .0025″ were too great successfully to trace wave lengths of approximately the same magnitude.

一部の識者の間では、2ミルから2.5ミルといった再生針先端の曲率半径では、ほぼ同じ大きさの波長をトレースするには大きすぎる、と考えられてきた。

Tests were therefore made by Columbia under carefully controlled conditions, to allocate the frequency response loss as a function of the recording stylus — the recording lacquer — the reproducing stylus and the reproducing head.

そこでコロムビアは、慎重にコントロールされた条件下で、周波数特性の損失を、録音針、ラッカー盤、再生針、再生ヘッドの関数として割り出すテストを実施した。

“Notes on the Development of Hot Stylus Recording”, Audio Record, Vol.34, No.6, June 1950, pp.1-3さりげなくすごいことが書かれていますね。ディスク録音で高域まで伸び切った再生ができない理由は、長らく再生機器側(ピックアップやトーンアームなど)が正しくトレースできていないせいだ、と考えられてきたのに、実はカッティング時の問題でそもそも十分に高域まで記録できていなかったことが分かってきた、というのです。それだけ、技術が向上し、また調査分析手法も向上してきた、ということなのでしょう。

Well, some surprising things are written very casually here. The decrease in hi-frequency response toward inner diameter had long been attributed to the reproducer side, due to poor tracking of pickups and tonearms. Then time went by, and the recorder side’s characteristic turned out to be the reason of the decrease. The realization would be possible by the progress of the technology, as well as the progress of the measurement and analysis.

Bachman 氏の論文からの引用は続き、高S/N比を保ったまま十分に高域まで記録する方法を探るべく行われた、さまざまな実験の結果について、簡潔な要約が記されています。

This article continues to quote more from the Bachman’s paper, briefly summarizing the experiments conducted by Mr. Bachman, for keeping the high signal-to-noise ratio while avoiding the decrease in high-frequency response.

Columbia’s engineers assumed, therefore, that the smoothing action of the burnishing facets on the cutting stylus was the result of heat generated by friction, which tended to “flow” a smooth surface on the cut groove. As cutting speed diminished, so would the amount of heat generated, and the smoothing action as well.

従ってコロムビアのエンジニアは、カッター針の「Burnishing Facet」が、生じる摩擦熱でスムーズにカッティングしており、その結果カットされた溝がスムースな表面を形成していると考えた。そして(カッティングが内周に向かい)線速度が落ちるにしたがい、発生する摩擦熱も減り、結果として徐々にスムースなカッティングとならなくなる、という仕組みである。

This theory would explain the increase in surface noise. But what about the reduction in high-frequency response?

これにより、サーフェスノイズ増加の理屈は説明できたことになる。では高域レスポンス減少の理屈についてはどうであろうか。

The shape of the cutting stylus gave an important clue here also. Since wax cutting styli, without burnishing facets, gave less high-frequency loss than lacquer styli, it could be seen that the burnishing facets introduced additional resistance to lateral movement of the cutting tool. This would also explain why the response tended to fall off more sharply at reduced groove diameter, too. For, with a fixed frequency, the relative proportion of lateral movement for a given forward travel increases as cutting speed decreases with inward travel of the groove. The reduced temperature of the stylus at the slower speeds would tend to increase this resistance to lateral movement still further.

ここでもまた、カッター針の形状が重要な手がかりとなった。かつてのワックス盤用カッター針には「Burnishing Facet」がなかったので、ラッカー盤用カッター針に比べて高域ロスが少なかった。このことから、「Burnishing Facet」が、カッティング時の「横方向」の動きに対する抵抗になっていると考えられる。これは、カットされた溝の径が小さくなると、応答が急激に低下する傾向があることも説明できる。周波数が一定であれば、溝が内側に向かうにつれて線速度が低下するため、カッティング方向の移動量に対する(カッター針の)横方向の移動量の割合が増加することになるからである。また線速度が低下すればカッター針の温度が下がるため、横方向の動きに対する抵抗がさらに大きくなる傾向がある。

“Notes on the Development of Hot Stylus Recording”, Audio Record, Vol.34, No.6, June 1950, pp.1-3Pt.6 セクション 6.1 に登場した「ワックス盤」は、ラッカー盤より非常に柔らかいため、「Burnishing Facet」のないカッター針で問題なく緻密にカッティングできていたということですね。もしかしたらこれが、米国において、特に RCA Victor において、1940年代半ばまで(または1948年近くまで)、ワックス原盤によるカッティングが長らく続けられていた、という説(Pt.3 セクション3.6 参照)がある理由のひとつなのかもしれませんね。実際のところ RCA Victor が市販用レコードのマスターとしてワックス盤をいつまで使っていたのかは分かりませんが、「ホットスタイラス」方式が一般的になるまでは、ラッカー盤へのカッティングには、今まで述べてきた S/N比 vs 高域レスポンス の問題があったわけなので。

The wax master discs, as we previously learned in Pt.6 Section 6.1, were very softer than lacquer-coated discs, so the cutting stylus without “Burnishing Facet” could easily cut minutely and smoothly with no issue. In this perspective, I remember the controversy of until when RCA Victor used wax disc for cutting commercial records — until mid-1940s or until 1948 (see: Pt.3 Section 3.6). I could not identify when RCA Victor switched from wax discs to lacquer discs for commercial recording, but as a matter of fact, there had been a serious issue of “S/N ratio” versus “high-frequency response” in lacquer recordings, until the “Hot Stylus” technique became popular.

source: “The Art and Science of Acoustic Recording: Re-enacting Arthur Nikisch and the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra’s landmark 1913 recording of Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony, Kolkowski, Miller, Blier-Carruthers, Science Museum Group Journal, Spring 2015 (online). © Aleks Kolkowski

1913年のニキシュ+ベルリン響のアコースティック録音 + ワックス原盤録音を再現する研究プロジェクトで復刻されたワックス原盤(本稿Pt.6 セクション6.1 参照)

a recorded wax disc, produced and used in the historical research to re-enact the 1913 acoustical recording of Nikisch and Berlin Philharmonic. (see: Pt.6 Section 6.1 of my entire article)

Columbia decided, therefore, to apply the required amount of heat to the stylus by external means — making stylus temperature independent of the cutting speed. The first method tried, in 1948, was to wind a small coil of wire directly on the sapphire stylus, heating it by means of direct current passed through the coil. This method worked so well that it is still in use today, although many other heating methods were investigated.

従ってコロムビアは、カッター針の発生する熱を(カッティング時の摩擦熱に頼らず)外的な方法で与えることにした。つまり、カッティング速度に依存せず、カッター針の温度を保つようにしたのである。1948年に最初の方法が試され、それはサファイア針に直接電熱線コイルをまきつけて直流電流を流し、熱するというものである。他の手法も調査研究されたが、この方法が非常にうまく機能したため、現在でも使われているものとなっている。

(…snip…) Columbia’s development of hot-stylus recording therefore appears to be a practical solution to the problems of background noise and frequency response loss. It apparantly offers all the advantages of wax recording, without sacrificing the convenience of lacquer discs for direct playback and easy processing.

(…中略…) 従って、コロムビアによる「Hot Stylus」録音手法の開発は、バックグラウンドノイズの問題と高域レスポンス損失の問題の両方に対する実用的な解決手法である。ワックス盤録音の利点を全て備え、同時に、録音直後にすぐに再生可能でかつ(プレス原盤を作る際の)便も備えるラッカー盤録音の利点を損なわないものといえる。

“Notes on the Development of Hot Stylus Recording”, Audio Record, Vol.34, No.6, June 1950, pp.1-3そして当 Audio Record 誌の記事は、Columbia および Bachman 氏の先行開発であることをしっかり指摘した上で、Fairchild 社から同じ手法で開発され販売されている Fairchild Thermo-Stylus Kit の説明に移ります。

Followed by the excellent summary, Audio Record article continues to the introduction of Fairchild Thermo-Stylus Kit, developed using the very similar technique as Bachman’s Heated Stylus technique (also, the article pointing out that the development of Columbia and Bachman precedes Fairchild’s product):

Prefected equipment for the application of this principle was announced by the Fairchild Recording Equipment Corporation last April. The Fairchild “Thermo-Stylus Kit”, illustrated in Fig. 4, includes a cutter-head adapter, two special cutting styli with built-in miniature heating elements (one stylus for standard and the other for microgroove recording), and a thermo-control box, with on-off switch, variable heat control, pilot light, and an illuminated meter, color calibrated to indicate the thermal settings for standard and fine-pitch recording. The control setting is non-critical, as good results are obtainable with a relatively wide latitude of stylus temperature.