EQカーブの歴史、ディスク録音の歴史を学ぶ本シリーズ。前回 Pt.16 では、第二次世界大戦勃発に端を発した物資不足から「サファイア・グループ」という業界エンジニア交流コミュニティが生まれ、企業秘密による競争から業界をあげての情報公開・技術標準化への動きがうまれたことを学びました。

On the previous part 16, I learned on the history of the “Sapphire Club” aka “Sapphire Group”, that was formed during the WWII because of the shortage of industry materials, and led the standardization in the industry, from the competition with trade secrets to the open collaborations, especially among the engineers.

同時に、その「サファイア・グループ」をきっかけとして、戦後の Audio Engineering 誌の発刊、およびオーディオ工学専門学会 Audio Engineering Society の誕生に繋がった流れを学びました。最後に、初の統一再生カーブである「AES 標準再生カーブ」について詳細を学びました。

At the same time, I learned the foundation of the Audio Engineering magazine as well as the Audio Engineering Soeicty, as a result of collaboration through the Sapphire Group. Then I learned the details of the “AES Standard Playback Curve”, the first advocated standard characteristic for commercial records.

調査に手間取るなどして少し間があいてしまいましたが、今回の Pt.17 では、LP黎明期〜AES標準再生カーブ発表の1951年1月〜統一前夜(最終的に米国各業界内で統一がなされる 1953 NARTB / 1954 改訂 AES / 1954 RIAA 策定の直前)、までの状況を調べていきます。めちゃくちゃ長い記事になってしまいました(笑)

This time as Pt. 17, after a few months of absence (due to the continuous research etc.), I am going to continue learning the history of disc recording, especially during the period: from the advent of LP records, publication of the AES curve in Jan. 1951, to the eve of the industry standardization (formations of 1953 NARTB / 1954 new AES / 1954 RIAA). Please note, this part is going to be an extraordinarily lengthy article 🙂

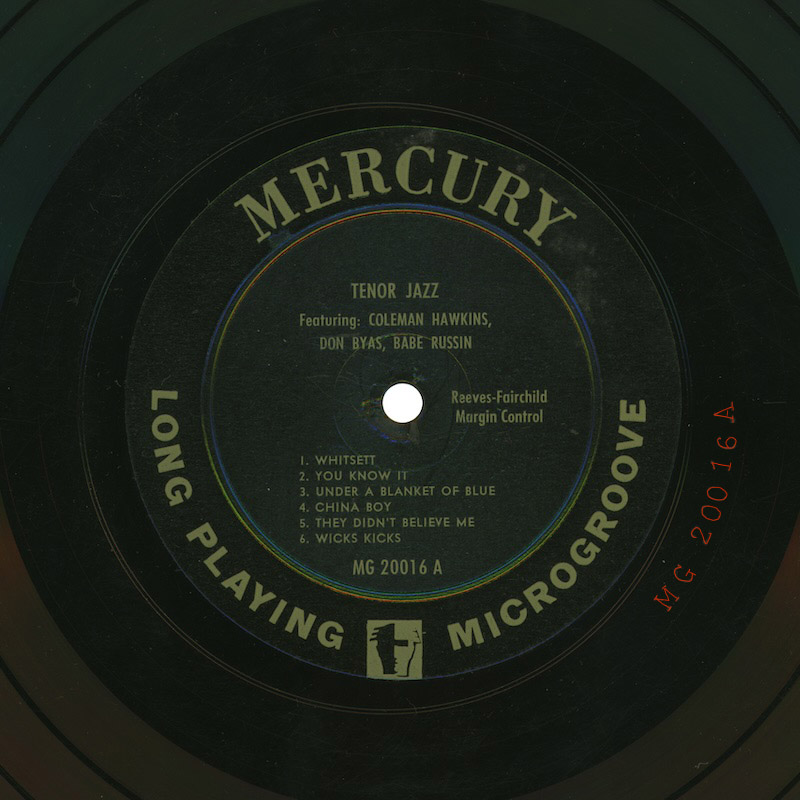

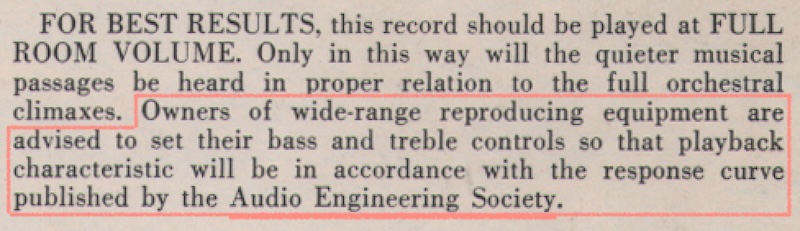

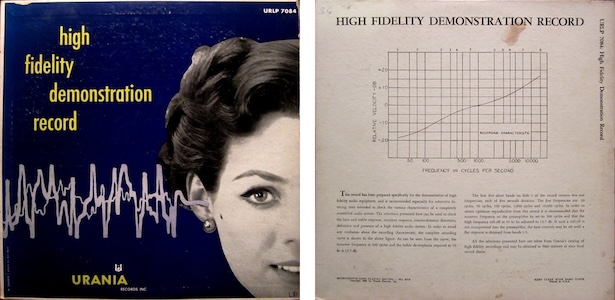

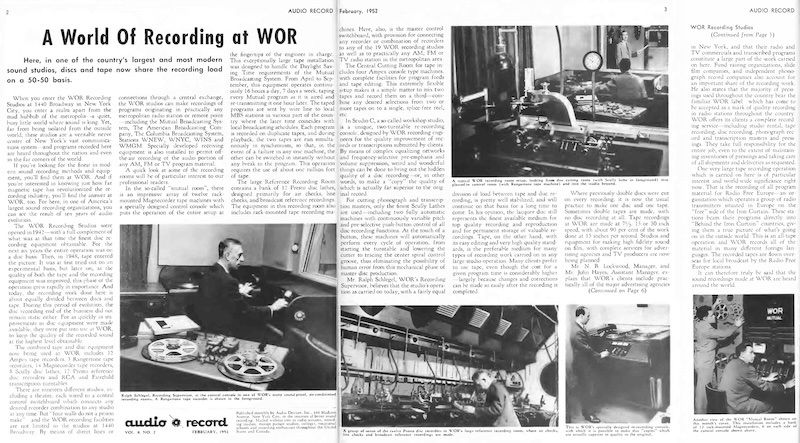

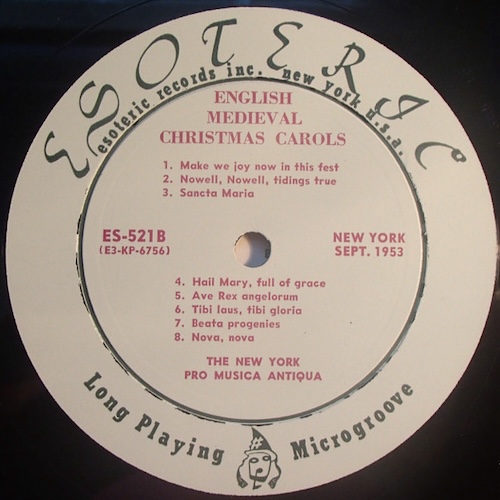

“About This Recording…” section of Mercury MG-50000 (1951), recommending AES playback curve.

Mercury MG-50000 (1951) の裏ジャケより。AES 再生カーブが指定されている。

毎回書いている通り、筆者自身の学習過程を記したものですので、間違いの指摘や異論は遠慮なくお寄せください。

As I noted in every part of my article, this is a series of the footsteps of my own learning process, so please let me know if you find any mistakes on my article(s) / if you have different opinions.

いつも相当長い文章ですが、今回は特に長くなってしまいました(笑)ので、さきに要約を掲載します。同じ内容は最後の まとめ にも掲載しています。

Again, this article become very lengthy — much longer than usual? — so here is the summary of this article beforehand (the same summary are avilable also in the the summary subsection).

LPや45回転盤などマイクログルーヴ盤の登場直後は、ヴァイナル組成もプレス技術も発展途上であり、新品であってもスクラッチノイズが入るなど品質に問題があった。また、当初は78回転盤アルバム音源の盤起こしによるLPイシューがほとんどであった。

In very early years of microgroove records (LPs and 45 rpms), both vinyl resin composition and pressing technology were still developing; even new records had scratch noise. Also, almost all LPs of such early years were reissues and compilations of 78 rpm albums.

マイクログルーヴ盤登場時期と、スタジオへの磁気テープ装置導入が一気に進む時期が奇跡的に一致していたことから、スタジオにおける長時間レコード制作時の自由度が飛躍的に向上した。また、1950年代前半になると、Pultec EQP-1/1A に代表される汎用可変イコライザが一気に普及し、リミッタ、コンプレッサ、ローパスフィルタ、ハイパスフィルタ、エコーチェンバ、プレートリヴァーブと相まって、ディスク録音EQとは独立して自由に音作りができる環境が整っていった。

It was a coincidence that the advent of microgroove records and the diffusion of magnetic tape recorders came out almost simultaneously. Both contributed the freedom of making longer playing records. Also in the early 1950s, variable (program) equalizers like Pultec EQP-1/1A became instantly popular among the studios, as well as limiters, compressors, low-pass/high-pass filters, echo-chambers and plate reverb, all of which gave studio engineers the freedom of sound-making as they wished, independent from disc recording EQ curves.

ディスクマスタリング(カッティング)時に用いられる録音EQは、ほとんどのスタジオにおいては、当時は固定回路のパッシブLRC EQ が用いられるのが慣例だった(現在は固定回路のアクティブ RC EQ が主流)。可変イコライザをディスク録音 EQ として使用する例もごく一部認められるものの、例外的なものであったと考えられる。

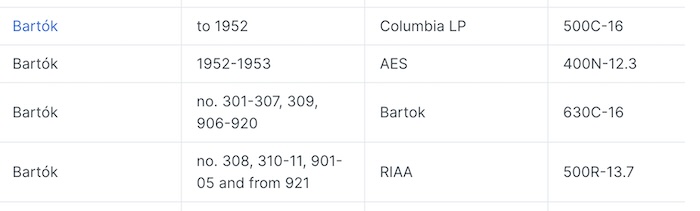

そもそも、大手レーベルでは社内で規格や技術プラクティスが厳格に定められていたため、エンジニアの気まぐれで記録特性を変更することは許されなかった。また、ほとんどの独立系スタジオにおいては、コストの問題から固定ユニットによる単一記録特性が選択されていたと思われる。一方、Peter Bartók のように、2〜3種類の録音カーブをレーベルごとに意図的に使い分けてマスタリングしたと思われる例外的な事例も見受けられた。

Disc recording equalizers which were used for mastering (cutting) lacquers at that time were almost always fixed LRC passive EQ units in most studios, although there was a very rare exception of using variable equalizers as disc recording equalizers.

More importantly, major labels had strict in-house standardization and engineering practices: recording engineers of such labels could not alter the recording equalizer with his/her passing fancy. Also, for many independent studios, it was highly probably an economical factor of choosing a single recording characteristics with a fixed EQ unit. On the other hand, we see there was an exceptional case, such that Peter Bartók intentionally used several recording characteristics depending on the labels.

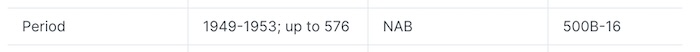

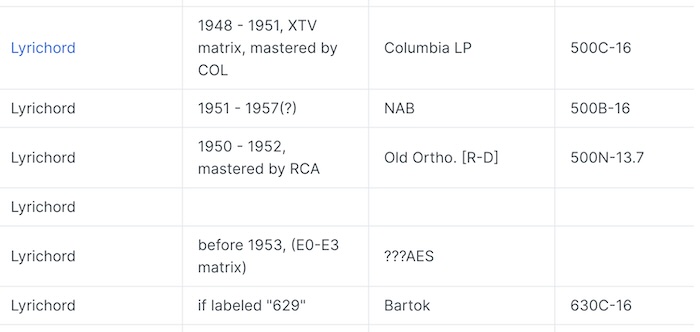

High Fidelity 誌に掲載された一連の “Dialing Your Disks” のデータは、掲載開始直後は「想定している再生カーブをレーベルに直接問い合わせて回答された」ものを掲載していたが、徐々にカテゴライズや情報が錯綜し、結果として後年の混乱の一翼を担うこととなった。一方、当時のさまざまなLPのマトリクス情報をつつきあわせると、「レーベルごとの特性」というよりは「マスタリングスタジオごとの特性」という傾向がつかめる。その上で最初期の “Dialing Your Disks” データを眺めると、ある種の一貫性を感じ取ることができる。

A series of data on The High Fidelity Magazine’s “Dialing Your Disks” initally consisted of the responses directly from the labels, “which reproducing characteristics each label intended to be used”. However, as the issue went by, there was a confusion of information and categoraization — as a result, “Dialing Your Disks” would strenghen the controversy in later years. On the other hand, by checking and comparing the dead-wax matrix information of actual records, it is clear that the used EQ depends on which mastering studio was used, rather than from whcih label the record was released. With this prerequisite in mind, we see some consistency among the early “Dialing Your Disks” data.

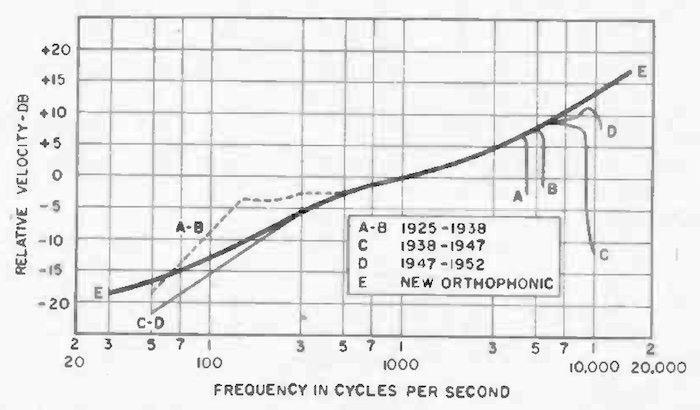

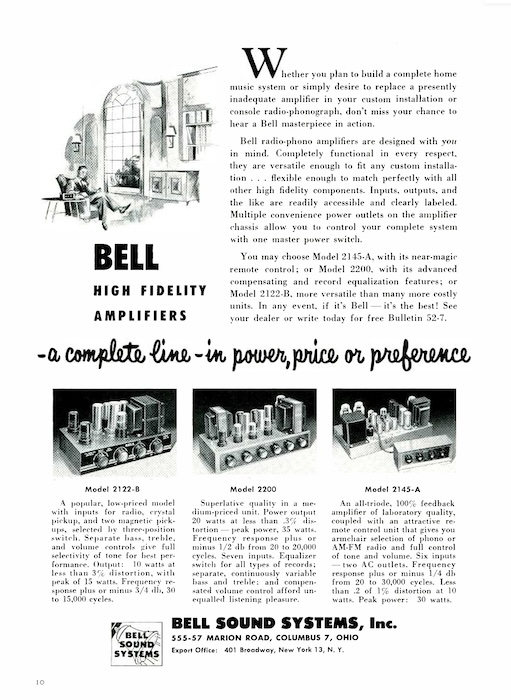

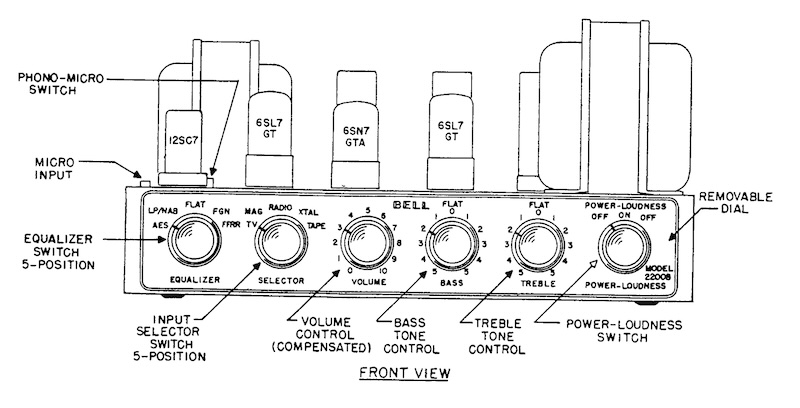

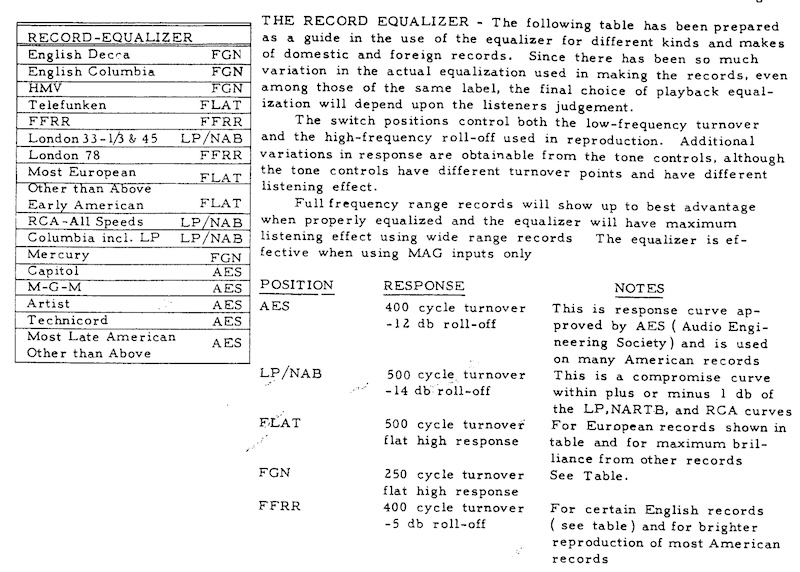

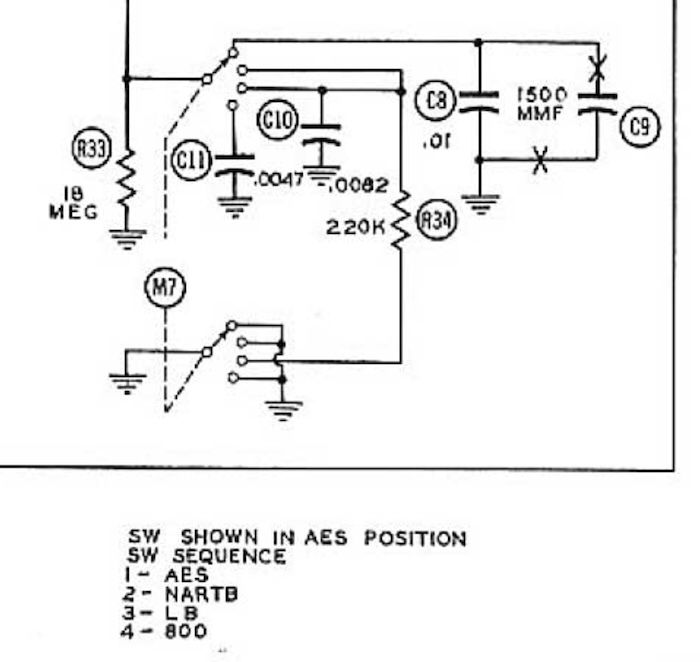

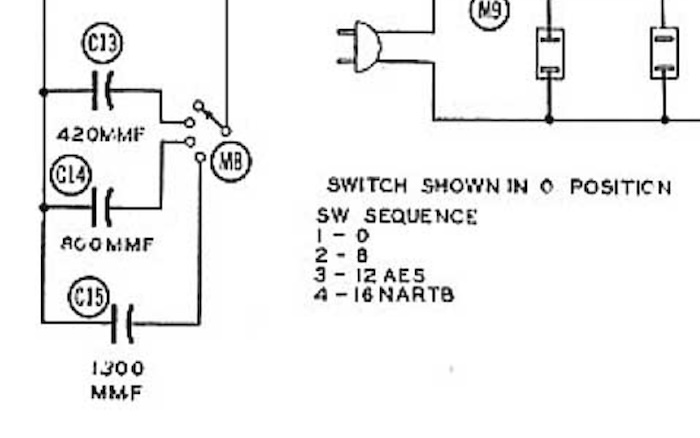

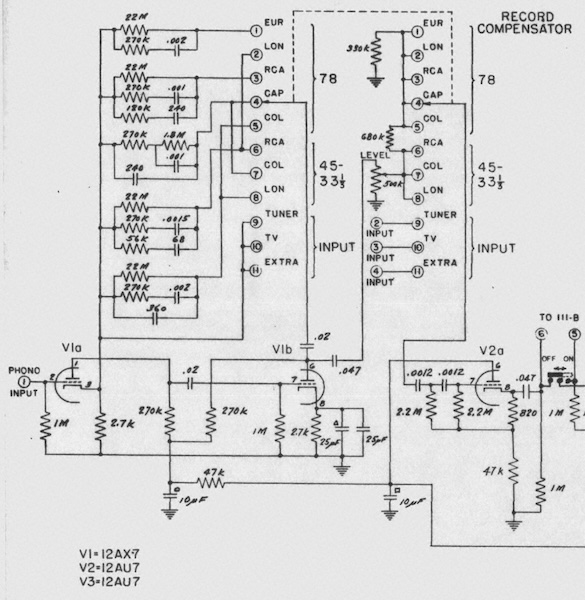

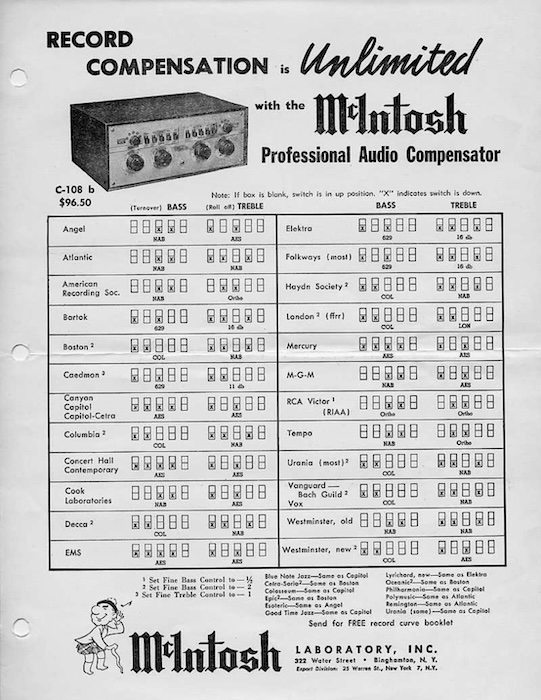

当時ハイファイブームに乗ってマニア向けに販売されていた可変EQ付アンプのセレクタをみてみると、1953年7月に放送局向けに策定された NARTB 録音再生規格、1954年1月に発行された改訂 AES 再生カーブ、1954年2月に発表された RIAA 標準録音再生規格、それら全てがまだ存在していなかった時期(〜1953年後半)では、RCA (Old/New Orthophonic) ポジションを備えたものはほとんどなく、NAB (≒ Columbia LP) と AES をメインとしていることが分かる。なかにはマイクログルーヴ盤向けには AES のみという機種もあった。

そして、同じカーブ名のポジションであっても、アンプごとに実装が異なるため、必ずしも同じ再生カーブではなかったことも分かった。

改めて、各レーベルが当時 High Fidelity 誌の “Dialing Your Disks” に回答した「想定カーブ」は、当時流通していたアンプのどのEQポジションでの再生を推奨するか、であり、特定の録音カーブの使用を回答したのではなかったと考えられる。

Early 1950s was also a beginning of “Hi-Fi” fad: some consumer amplifiers for audio fanatics had variable / selectable phono compensator (reproducing characteristic switcher). It is interesting to know that many of early amplifiers (before the publications of Jul. 1953 NARTB Standards, Jan. 1954 new AES Playback Standards and Feb. 1954 RIAA Characteristic) only had “NAB (≒ Columbia LP)” and “AES” positions: few had “RCA” (new/old Orthophonic) positions. On some amplifiers, there was only one switch for reproducing microgroove records — “AES” only.

It was also found that even positions with the same EQ curve name did not necesssarily have the same playback curve due to different implementations in different amplifiers.

Once again, the “assumed curves” that each label responded to High Fidelity magazine’s “Dialing Your Disks” at the time were the recommended playback at whatever EQ position(s) on the amplifiers in circulation at that time, not the use of specific recording curve(s).

Contents / 目次

- 17.0 Before We Proceed

- 17.1 More About Early LPs

- 17.2 The Advent of Magnetic Tape Recorders

- 17.3 Reeves Sound Studios as of 1949 / Fine Sound Studios as of 1952

- 17.3.1 All the Mercury releases around 1949 were cut at the Reeves Sound Studios

- 17.3.2 Ormandy & Philadelphia Philharmonic at Reeves Sound Studios on May 10, 1949

- 17.3.3 Reeves Sound Studios in 1949 using the NAB curve for commercial records as well

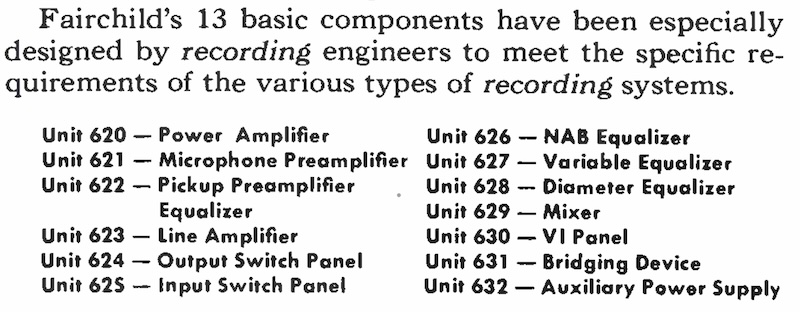

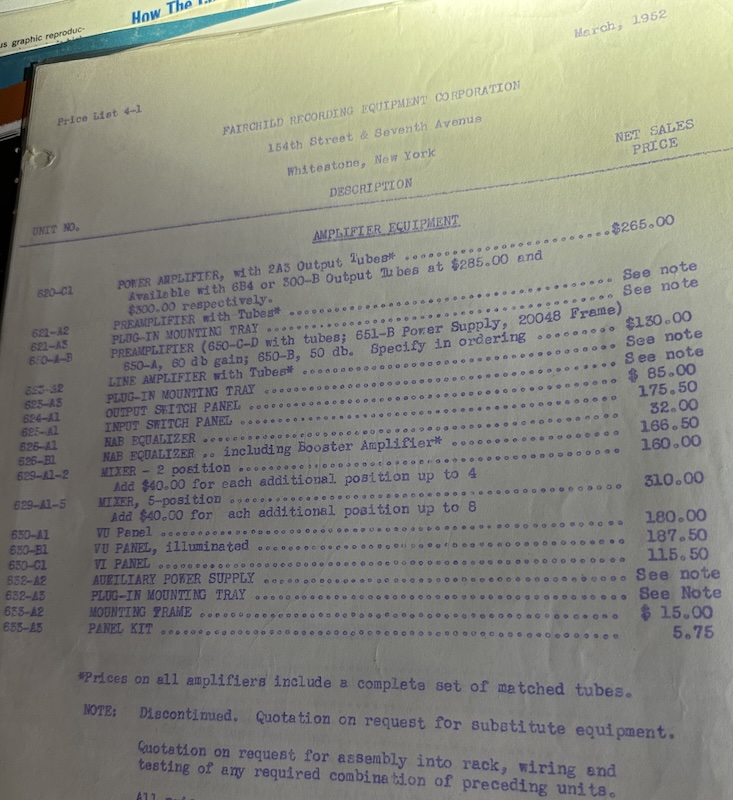

- 17.3.4 Fairchild Unit 627 Variable Equalizer

- 17.3.5 Fine Sound Studios as of 1952

- 17.4 The Advent of Program (Variable) Equalizer

- 17.5 Before and After the 1951 AES Curve, Until the RIAA Curve

- 17.5.1 Columbia and its studios

- 17.5.2 RCA Victor and its studios

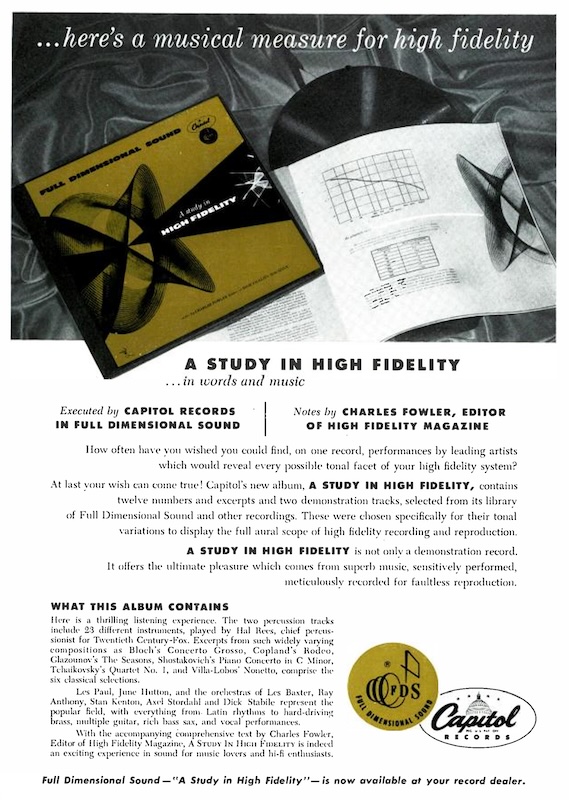

- 17.5.3 Capitol and its studios

- 17.5.4 Reeves Sound Studios (Mercury, etc.)

- 17.5.5 WOR Recording Studios and Blue Note (early LP years, before Van Gelder years)

- 17.5.6 Good Time Jazz / Contemporary label (early years)

- 17.5.7 Peter Bartók Studios and various labels

- 17.5.8 US Decca and London

- 17.6 Early list from “Dialing Your Disks”

- 17.7 Phono Amplifiers in the early 1950s (before RIAA)

- 17.7.1 Bell Sound Systems Model 2200

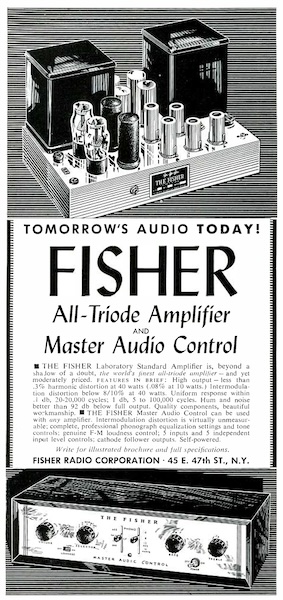

- 17.7.2 Fisher 50-C Master Audio Control

- 17.7.3 Newcomb Classic 25

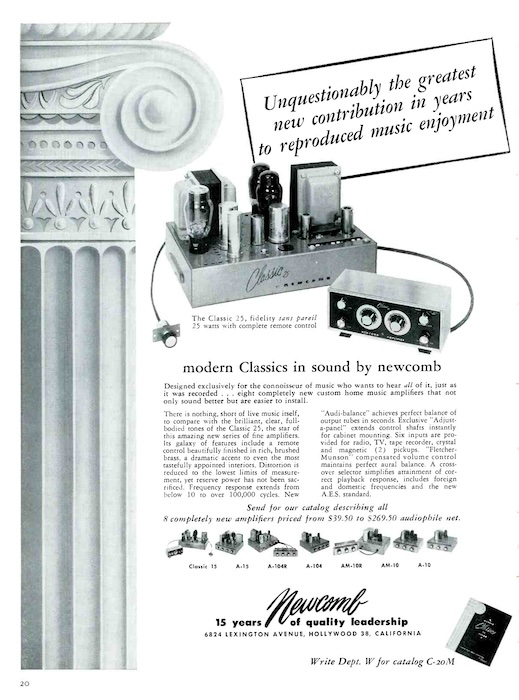

- 17.7.4 Marantz Audio Consolette (1951)

- 17.7.5 Stromberg-Carlson AR-425

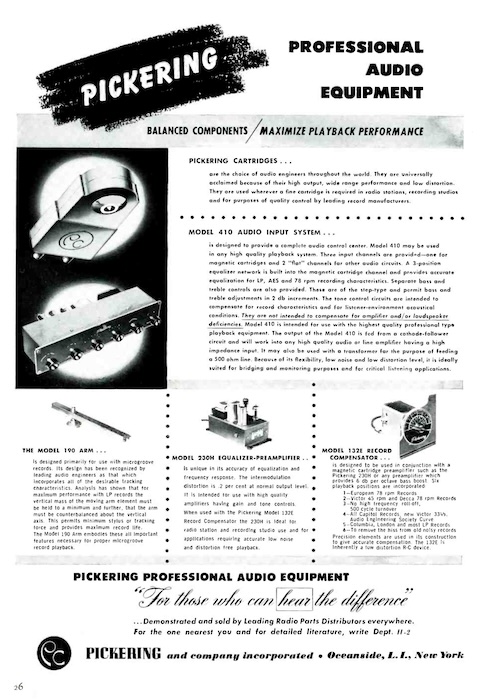

- 17.7.6 Pickering 230H + 132E / Model 410

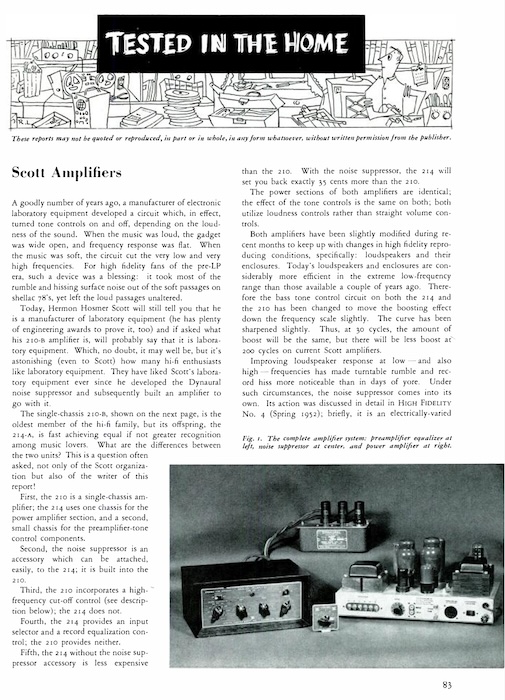

- 17.7.7 H.H. Scott 120-A

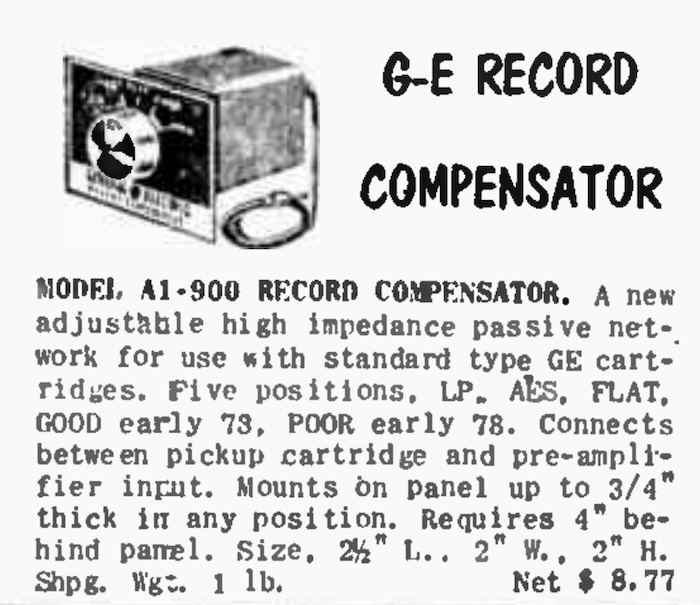

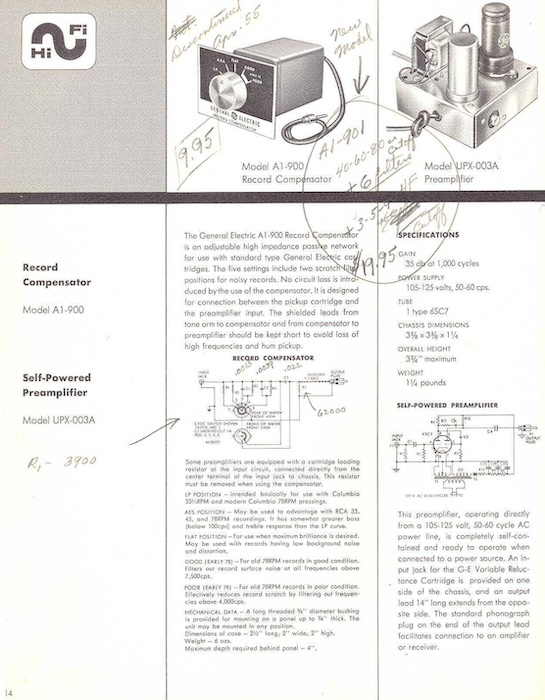

- 17.7.8 General Electric A1-900 Record Compensator

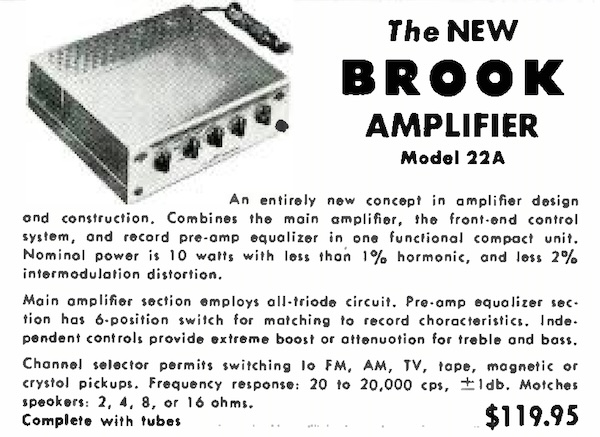

- 17.7.9 Brook Model 22A

- 17.7.10 Some Thoughts (or Hypothesis)

- 17.8 The summary of what I got this time / 自分なりのまとめ

17.0 Before We Proceed

拙シリーズ記事を参考に各種SNSなどで論を展開される場合、第三者が確認できるように、該当する記事のURLなどを添えて参照していただけるとうれしいです。

私も自分自身が書くものについては、参考/引用/出典を全て(可能な限りリンク付きで)明らかにしているつもりです。リファレンスなき引用や参照は、元記事を書いた方や情報提供してくださった方に失礼であると考えますので。

参考にして頂けること自体は大変喜ばしいことで、ありがとうございます。

17.1 More About Early LPs

1948年6月〜に出されていた「米国における」最初期の LP について、もう少しその特徴をみていきましょう。

Here are some more of the characteristics of the “USA” LPs from the early years, issued from June 1948 and onward.

17.1.1 Inferior quality of early vinyl resin

本稿でも何度か引用している Susan Schmidt Horning 氏の書籍 “Chasing Sound: Technology, Culture, and the Art of Studio Recording from Edison to the LP” (2013, The John Hopkins University Press) に、こんな記述があります。1999年5月5日に Wilma Cozart Fine (1927-2009) に電話でインタビューした内容の引用です。

Susan Schmidt Horming’s book “Chasing Sound: Technology, Culture, and the Art of Studio Recording from Edison to the LP” (2013, The John Hopkins University Press), which I have cited several times in this entire series, has an interesting quote from a telephone interview with Wilma Cozart Fine (1927-2009) on May 5, 1999.

The microgroove LP, running at 33⅓ rpm, the same speed as electrical transcriptions, offered playing time on a single twelve-inch disc of up to nearly forty-five minutes using both sides, enabling an entire symphony to be available on one record. Pressed on Vinylite, a lighter and more flexible material than shellac, they were nonbreakable and virtually free of needle scratch, an unfortunate result of the filler in shellac which one recording engineer likened to “softened asphalt scraped up off the roads.

マイクログルーヴLPの回転数は放送局で使用されていたトランスクリプション盤と同一の33 1/3回転であった。これにより、1枚の12インチ盤に両面で約45分間の収録が可能となり、交響曲を1枚のレコードに収められるようになった。シェラックより軽量で柔軟な素材であるヴィニライトにプレスされたLPは、割れる心配もなかった。ある録音技師が「道路を削りとったアスファルトを柔らかくしたもの」と例えていた抗摩耗剤、それがシェラック盤には含まれていたが、LPはそのスクラッチノイズから解放されることとなった。

However, Mercury Living Presence record producer Wilma Cozart Fine, another pioneering woman in the male-dominated recording industry, recalled that some early vinyl was also inferior, and it took some time before high-quality vinyl was developed, which was particularly important for classical music.

しかし、男性に支配されたレコード業界におけるパイオニアたる女性のひとり、Mercury Living Presence のプロデューサ Wilma Cozart Fine 女史の回想によると、初期のヴァイナル盤の品質もあまり良くないものであったし、クラシック音楽レコードの製造に特に重要である高品質ヴァイナルが開発されるまでには数年を要した、とのことである。

“Chasing Sound: Technology, Culture, and the Art of Recording from Edison to the LP”, p.110, by Susan Scmidt Horning, The John Hopkins University Press, 2013.確かに、特に最初期(1948年〜1951年頃)の LP 盤の中には、Mercury に限らず、あまり柔軟性がなく硬質な素材だったり、見た目は無傷なのにスクラッチノイズが少なからず聴こえたりするものがあったりします。

Indeed, I find some LPs — especially from the early years (around 1948-1951) — are not very flexible and are made of harder materials, not only Mercury’s but also those from other labels. On some LPs scratch noise can be heard, although they look intact.

上記の電話インタビューで語られている話は、Mercury レーベルが所有していた当時のプレス工場に限った話なのかもしれません。

In a sense, the story told by Mrs. Wilma Cozart might be specific to the pressing plants around that time, owned by Mercury Records Corporation.

しかし、たまに入手する、黎明期(1948年〜1950年代前半)のLP盤の中には、確かに(現在のレベルと比べると)新品当時から品質が劣っていたのでは、と感じることが少なくありません。これは、保管状態の問題でもなく、もちろん再生EQカーブの問題ではなく、単純に当時のヴァイナル素材の組成に関する当時の技術や品質の問題、そしてプレス品質の問題だったものもある、ということでしょう。

On the other hand, I sometimes encounter LPs of various labels from the early years (1948 to early 1950s), which sound with many scratch noises even though they look like new — I believe they were poorly made. I guess it’s not because of poor storage conditions through the years; not bacause of the improper reproducing characteristics; but some quality issues of vinyl composition as well as poor pressing quality at that time.

西ドイツ盤や日本盤に比べると、盤質やプレス品質が平均して下回っている、と言われることもある(笑)米国盤ですが、もしかしたらLP登場直後からずっとそうだったのかもしれませんね。

I hear some people say that the quality of American record compositions (and the pressing quality of the U.S.) are inferior in general, to those from West Germany and Japan — not sure if it’s correct, but it might be true, even since the very early LP years.

さらに時代が進むと、米国では特に1960年代の45回転盤はLP製造時の端材だったり粗悪な品質のヴァイナルでプレスされているものが多かったことが知られています。これらは「大量生産の消耗品としてのレコード盤」という意識、言い換えると「コスト意識」がより強かった、経済大国アメリカ合衆国ならではなのかもしれませんね。

Also in the U.S., it is known that many 45 rpms (especially from the 1960s) were pressed with poor quality vinyl resins (and/or remnant of LP manufacture). It may be unique to the U.S., an economic powerhouse with a stronger awareness of “vinyl records as mass-produced consumables” — in other words, a stronger “cost-consciousness”.

ともあれ、LP最初期においては、ヴァイナル化合物組成や製造の技術も、マイクログルーヴによるカッティング機材や技術も、まだまだ黎明期であり、そこから数年でどんどん進化と品質向上を遂げていくことになるわけです。

Anyway, in the early-early LP era, everything was still under development — vinyl resin composition, microgroove cutting equipments and techniques, etc. Then within a few years, they would be greatly improved in quality.

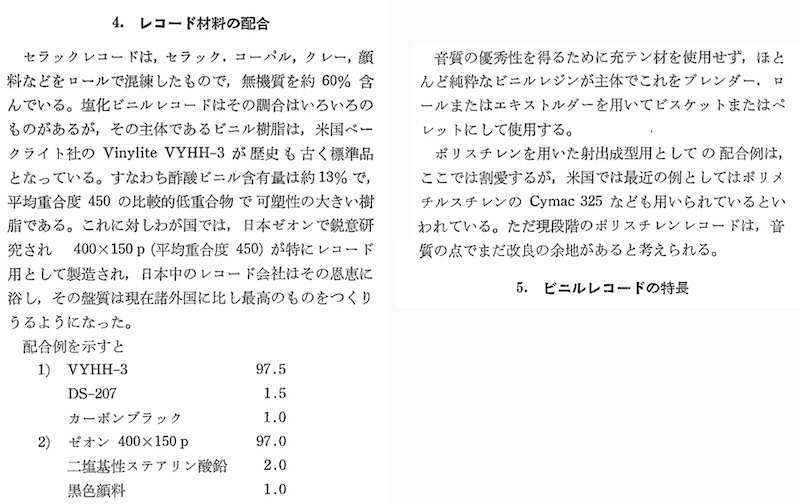

たまたま見つけたものですが、高分子学会 の論文誌 1959年8巻7号 に、「人工高分子のレコード」という解説記事が掲載されています。著者は日本グラモフォンの柳本孝男氏で、1957年に京都大学で理学博士号を授与された方のようです。

I found an interesting technical article by chance: “Synthetic Polymer Records” (1959), published in the Vol. 8, No. 7, the Journal of The Polymer Science (Jpaan). The author is Takao Yanagimoto of Nippon Gramophone, who received the Doctor of Science at Kyoto University in 1957.

1959年、ちょうどステレオLPが登場した直後というタイミングでもあり、レコード材料の配合比率という観点から非常に興味深いデータが多く掲載されているほか、1950年代後半における日本、米国のレコード製造事情も垣間見られ、同時にヴァイナルレコードの基礎知識解説もある、簡潔にまとめられた非常に貴重な資料だと思います。

This article was written in 1959, just after the stereo records were introduced. It describes plenty of valuable information, from the viewpoint of vinyl record’s composition. It also is an overview of vinyl record production both in the US and in Japan as of 1959, as well as an outline of the fundamental technology of vinyl records.

source: J-STAGE DOI https://doi.org/10.1295/kobunshi.8.364.

当時の米国では、ベークライト社の Vinylite VYHH-3 が、日本では、ゼオン 400×150p が、それぞれ広く使われていることが解説されている。同時に、ポリスチレン製レコードについても触れられている

This article explains the composition of the vinyl compound as of the middle-late 1950s: Bakelite Corporation’s Vinylite VYHH-3 widely used in the US, while Japan Zeon’s 400×150p used in Japan. Also there is a brief mention of polystyrene records.

17.1.2 Early LPs mostly from 78 rpm masters

最初期(1948〜1950)のLPに収録されていた音源のほとんどは、78 rpm アルバム音源の LP 化や、78 rpm シングル盤音源のコンピレーションでした。このLP黎明期は、磁気テープがスタジオに導入されだした時期と奇跡的に一致していますが、テープ導入前のごく最初期は、状態の良いシェラック盤、テストブレス盤、セーフティラッカー盤などからのダビングによって直接LPカッティングされていました。

Almost all of the sound sources on very early LPs (1948-1950) were 78 rpm albums or their compilations. The dawn of the LP miraculously coincided with the introduction of magnetic tapes into the studios. Before the introduction of magnetic tapes, LPs were cut directly by dubbing from good condition shellac records, vinyl test pressings, or safety lacquer recordings.

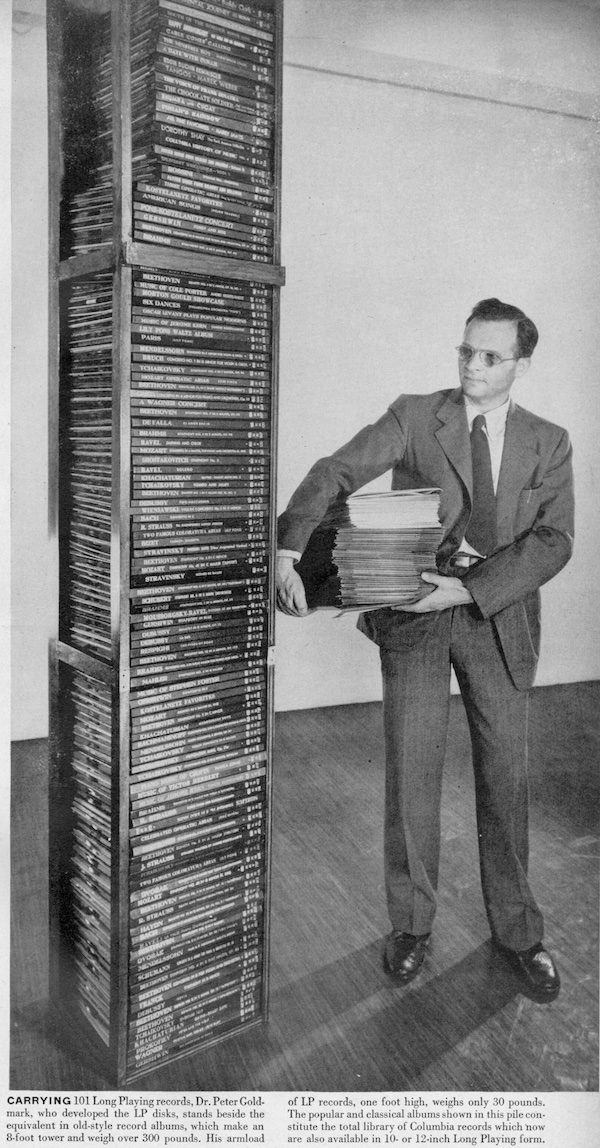

例えば、1948年6月18日にニューヨークのウォルドルフ・アストリアホテルで初お披露目され、間髪を入れずにリリースが開始された、 Columbia の世界初LPは101枚ありました(本稿 Pt.11 参照)。Peter Goldmark 氏のプレゼンで抱えていた101枚です。

For example, 101 LPs were initially released on June 18, 1948, when Coulumbia proudly presented the Long Playing Microgroove records for the first time (see: Pt. 11). In the press demonstration at Waldorf=Astoria Hotel, Peter Goldmark was holding the 101 LPs on stage.

source: LIFE Magazine, July 26, 1948, p.39

この101枚のLPの一覧は、“History of Longplay” というサイトの記事 “Columbia’s Initial 101 LPs Catalog” にもまとめられています。

The list of these 101 LPs is summarized at the article “Columbia’s Initial 101 LPs Catalog” of the “History of Longplay” website.

12インチクラシックLPが58枚(ML-4001〜4057 および ML-4071)、10インチクラシックLPが12枚(ML-2001〜2012)、12インチライトクラシックが12枚(ML-4058〜4067、4069、4070)、10インチライトクラシックが8枚(ML-2013〜2020)、10インチポピュラーが11枚(CL-6001〜6011)、の以上101枚です。

The 101 LPs consists of: fifty-eight 12-inch Classical LPs (ML-4001 to ML-4057, and ML-4071); twelve 10-inch Classical LPs (ML-2001 to ML-2012); twelve 12-inch Light Classical LPs (ML-4058 to 4067, 4069 and 4070); eight 10-inch Light Classical LPs (ML-2013 to ML-2020); and eleven 10-inch Popular LPs (CL-6001 to CL-6011).

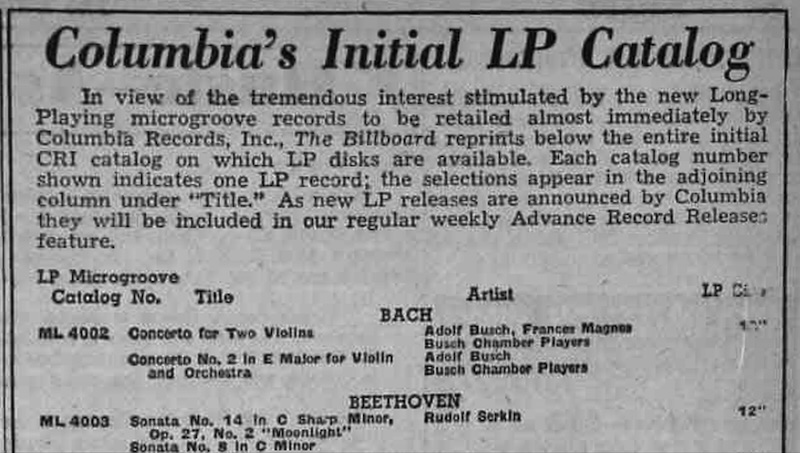

このリストは元々、The Billboard 1948年7月3日号 の 35ページ および 120ページ に “Columbia’s Initial LP Catalog” として掲載されたものです。

The list of the first 101 LPs was originally published in The Billboard, July 3, 1948 issue, p. 35 and p. 120, under the title of “Columbia’s Initial LP Catalog”.

source: “Columbia’s Initial LP Catalog”, The Billboard, July 3, 1948, p.35.

Billboard 誌1948年7月3日号に掲載された、Columbia 最初の LP リリース101タイトルの一覧(の冒頭部分)

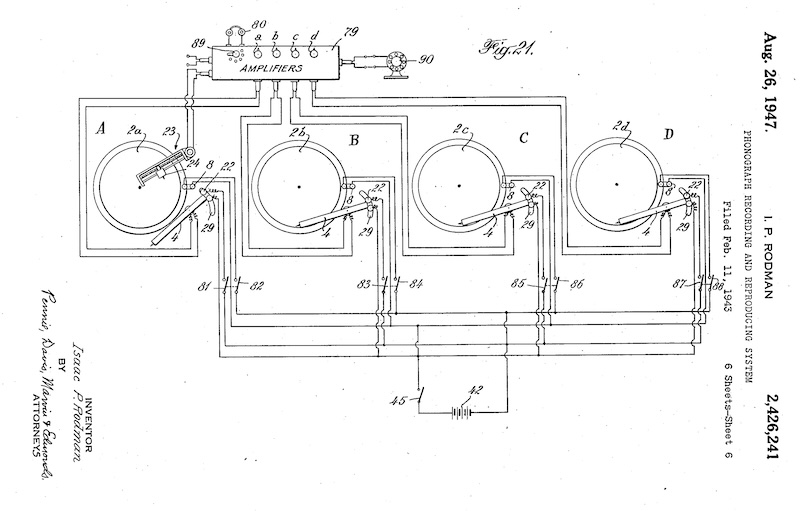

これら101枚のLPはすべて、78回転盤アルバム時代の音源のLP再発であり、Columbia が 1939年以降「将来に長時間レコードを出す時のために」録音し保管しておいた、16インチ 33 1/3 rpm のセーフティラッカーから直接マスタリングされています(この時に使われたダビングシステムは Columbia の Ike Rodman 氏によって特許 US2,426,241 となっています)。ちなみに 、Columbia が LP 制作時に磁気テープを使用し始めたのは早くとも1949年以降である、とされています。

All these 101 LPs were either the reissues of 78 rpm albums or the 78 rpm compilations. They were mastered directly from the 16-inch 33 1/3 rpm safety lacquers, which Columbia decided to record and keep since 1939. By the way, the transfer system from 16-inch safety lacquers to 12-inch lacquers was patented by Columbia’s Ike Rodman as US2,426,241. Also, it is known that Columbia introduced magnetic tape systems in the studio in 1949 at the earliest.

source: “US2,426,241A: Phonograph recording and reproducing system (Issac P. Rodman)”.

Columbia の Ike Rodman 氏によって出願された、複数枚のディスクから新たなブランクディスクに複製する装置の特許

一方、3大メジャーの残る2レーベル(RCA Victor と Decca)、およびその他ほとんどのレーベルは、当初 LP のリリースを行うにあたり、状態の良いシェラック78回転盤、テストプレスのヴァイナル78回転盤、(まんがいち残っていれば 78 rpm メタルマザー?)、などからの盤起こしにより、LP を制作していました。1948年〜1950年にスタジオに磁気テープ録音が次々導入されていき、新規録音はテープ録音・編集後カッティング、旧譜はテープにトランスファーしたのち編集してカッティング、となっていきます。

Other labels, including the remaining majors (RCA Victor and Decca), used shellac 78 rpms in good condition and vinyl test pressings (78 rpm metal mothers would possibly used if existed? not sure) for LP mastering. As magnetic tape recorders gradually introduced into the studios during 1948 to 1950, new recordings were recorded on tapes, edited on tapes, then mastered onto lacquer discs; old recordings (78 rpms) were transfered to tapes, edited on tapes, then mastered onto lacquers.

17.2 The Advent of Magnetic Tape Recorders

LP黎明期にとって大きかったのは、やはり、スタジオに 磁気テープが導入され始めたのがほぼ同時期だった ことでしょう。その大きなメリットとして以下のような点があげられます。

- 78rpmの旧譜音源をLP化する際の編集作業が、ディスクトランスファーに比べて大幅に便利になったこと

- ディスク録音では非常に困難(現実的には不可能)だった「スプライシング」などによる編集が容易になったこと

- 33 1/3 rpm LP や 45 rpm(さらには 78 rpm)といった、さまざまなフォーマットのディスクのマスタリング(カッティング)の元となる音源として使えるようになったこと

- 新録においては、片面3〜5分にとらわれない長時間記録が可能になった新メディアLPの片面(20分〜25分)以上に、テープ1本での長時間の連続録音が可能になったこと

- 演奏ミスやカッティングミスの際はラッカー盤を破棄するしかなかったが、磁気テープは消去後に再利用できること

One of the most significant factors in the early years of LPs was the fact that magnetic tape was introduced into studio at about the same period. Major advantages of magnetic tape recording (over direct wax/lacquer disc recording) are as follows:

- much more convenient editing work when converting old 78 rpm recordings to LP, compared to direct disc transfers

- easier editing by “splicing” etc., which was very difficult (or practically impossible) to do with disc recordings

- the ability to use it as a source for mastering (cutting) discs of various formats: 33 1/3 rpm LPs, 45 rpms (and even 78 rpms)

- allowing for longer recording times beyond the 3-5 minutes of the regular 78 rpms; even allowing for longer continuous recording on a single tape than the single-sided LP (20-25 mins)

- in the event of performance error or cutting error, the lacquer disc had to be discarded. but magnetic tapes could be reused after erasure

例えば、Mark Coleman 氏の著書「Playback: From the Victrola to MP3, 100 Years of Music, Machines, and Money」(2003)には、以下のような記載があります。

For example, Mark Coleman’s book “Playback: From the Victrola to MP3, 100 Years of Music, Machines, and Money” (2003) states the following:

By the late 1940s magnetic tape recording caught on with U.S record companies. Tape was quickly adopted as the initial step in the recording process. In the studio, recording on magnetic tape superseded direct recording on blank acetate discs. The advantages were dramatic: tape could run uninterrupted for thirty minutes, it could be played back immediately and, most important, it could be edited. Various segments of tape could be spliced together in perfect continuity, mistakes could be erased and effects (such as echo chamber) could be added. Music on tape could be meticulously worked over before being transferred to disc. At the same time, the flexibility and speed of using magnetic tape made the recording process cheaper and more accessible.

1940年代後半までに、米国のレコード会社の間で磁気テープ録音が流行した。録音プロセスの初期段階として、テープはすぐに採用された。スタジオでは、磁気テープ録音が、ブランクアセテート(ラッカー)ディスクへの直接録音に取って代わった。テープは30分間途切れることなく、かつ(録音が済めば)すぐに再生でき、さらに最も重要だったのは編集が可能だったことである。テープのさまざまなセグメントを完全に連続させて繋ぎ合わせたり、ミスを消したり、エコーチェンバーなどのエフェクトを加えたりが可能となった。つまり、ディスクカッティングする前に、テープに録音された音源に対して入念に作業を施すことができた。同時に、磁気テープの柔軟性とスピードは、録音プロセスをより安価で身近なものにした。

“Playback: From the Victrola to MP3, 100 Years of Music, Machines, and Money”, p.58, by Mark Coleman, Da Capo Press, 2003同様に、Susan Schmidt Horning 氏の著書「Chasing Sound: Technology, Culture, and the Art of Recording from Edison to the LP」にも、以下のような一節を確認できます。

Also in the Susan Schmidt Horning’s book “Chasing Sound: Technology, Culture, and the Art of Recording from Edison to the LP”, we see the following paragrah:

Quickly, word about the Ampex machines’ performance spread throughout the recording industry. (…snip…) Tape recording seemed a godsend, for it solved many of the problems associated with disc recording. It was capable of higher fidelity than disc recording because frequency response was not limited by the inertia of mechanical parts, dynamic range was not limited by the dimensions of the groove, and surface noise and needle scratch were eliminated from the original recording. Initially, record companies continued to record original masters on disc, using tape as a backup, as they were unwilling to rely on an unproven technology as the primary recording medium. This conservatism was well placed.

(ラジオ番組 The Bing Crosby Show における Ampex 200A の使用が成功裡に進んだことにより)Ampex テープレコーダの性能に関する話題がまたたくまにレコーディング業界全体に広まった。(中略)テープ録音は、ディスク録音における多くの問題を解決してくれるものとして、天の恵みとみなされていた。周波数特性が機械部品の慣性によって制限されることはなく、ダイナミックレンジが溝の寸法によって制限されることもなく、またサーフェスノイズやスクラッチノイズからも解放されるため、オリジナル音源としてディスク録音より高い忠実度を得ることができた。当初、レコード会社は、まだ実績が十分でない新メディアを主たる記録媒体にしたくはないと考え、オリジナルマスター制作は引き続きディスクで行い、バックアップとしてテープを使用していた。この保守的な方法論は信頼性が高かった。

“Chasing Sound: Technology, Culture, and the Art of Recording from Edison to the LP”, p.106, by Susan Scmidt Horning, The John Hopkins University Press, 201317.2.1 The Huge Impact of Ampex 200A / 201 / 300 / 301 Recorders

米国における、磁気テープ黎明期を代表する機器が、あの有名な Ampex 200A です。

The famous Ampex 200A represents the early days of magnetic tape recorders in the United States.

本稿では磁気テープ装置の歴史そのものをメインでは扱わないため、ここではこれ以上深掘りはしませんが、第二次世界大戦終了直前に連合軍がドイツ侵攻の際に AEG 製 Magnetophon を発見し、John T. “Jack” Mullin 氏が米国に持ち帰ったエピソード、Magnetophon の技術を参考にした Ampex 200 の開発における、ビング・クロスビー (Bing Crosby)のエピソード、そして Capitol が Bing Crosby Enterprises から購入した Ampex 200A シリアル番号33番(のちに Ampex 201 相当にアップグレードされた)など、非常に興味深いエピソードを伝える web サイトや記事、論文などを、以下にリンクで示します。

As this article does not deal mainly with the history of magnetic tape recorders itself, we will not delve further into the subject here. But here are some interesting topics and information: the discovery of AEG Magnetophon by the Allied Forces during their invation of Germany just before the end of WWII; John T. “Jack” Mullin bringing it to the U.S.; Bing Crosby’s episode in the development of the Ampex 200 which was based on Magnetophon technology; Ampex 200A serial number 33 (later upgraded to Ampex 201), purchased by Capitol from Bing Crosby Enterprises; etc.

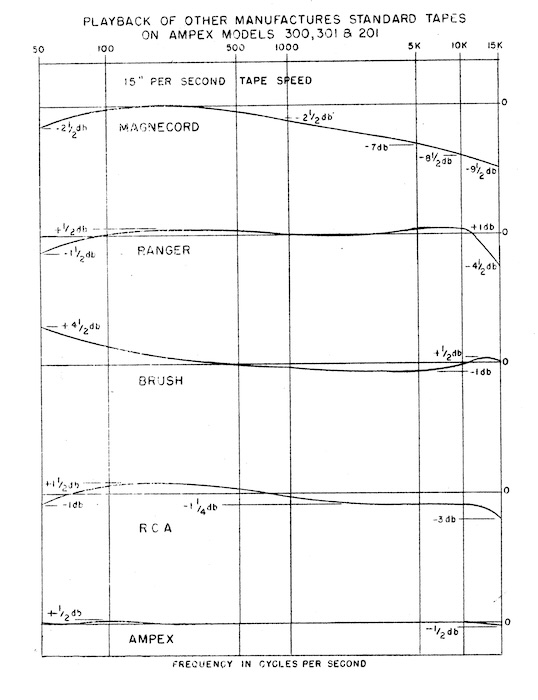

Capitol 用の(Ampex 200A を 300/301 相当にする)Ampex 201 変換キットのマニュアルには、1949年当時出回っていた各社テープの再生特性グラフ(AMPEXを基準とした場合)が掲載されており、ものの見事に特性がバラバラなのが興味深いです。

Ampex 201 Conversion Kit (converting Ampex 200A to the one similar to 300/301) for Capitol Records has an interesting documentation, featuring the graphs of playback frequency characteristics of various manufacturer’s standard tapes.

Mix 誌1985年4月号 には、西海岸(あるいは全米)を代表する独立スタジオ Radio Recorders の Harry Bryant 氏へのインタビューが掲載されており、その中でも磁気テープ導入時の興味深いエピソードが語られています。

April 1985 issue of the Mix magazine features the interview with Harry Bryant of Radio Recorders, including an interesting episode of the early days of magnetic tape recorders.

Bonzai: When did tape recording come in?

Bonzai: テープ録音はいつ始まったんですか?

Bryant: After the war, and we were one of the first studios to jump on the bandwagon. We had quite a few different models: Rangertone, Magnacord, and Presto, but Ampex made the only one that was 100% professional. It was the Cadillac of the industry and cost about $4,000. We worked very closely with Ampex and had about 20 of their machines by 1960. Through a series of trades we even ended up with the recorder that had serial number 1. We were the largest user of Ampex in the city.

Bryant: 戦後だね。我々は(磁気テープ装置という新しい技術の)流れに乗った最初のスタジオのひとつだった。Rangertone、Magnacord、Presto など、かなりの種類の機種を揃えていたけど、100% プロ仕様だったのは Ampex だけだった。いわば録音業界のキャデラックで、価格は当時 4,000ドルだった。我々は Ampex と密接に協力し、1960年までに約20台の Ampex を所有することになった。一連の取引を通じて、シリアル番号1番のテープレコーダまで手に入れられた。ここらでは我々は最大の Ampex ユーザだったね。

“Lunching with Bonzai: Radio Recorders' Harry Bryant”, by Mr. Bonzai, MIX, Vol. 9, No. 4, Aprio 1985, pp.33-401949年に Ampex 300 テープレコーダを導入した Atlantic レーベルの アーメット・アーティガン (Ahmet Ertegun) 氏と トム・ダウド (Tom Dowd) 氏も、その性能に驚いたそうです。

Atlantic started using Ampex 300 tape recorder(s) in 1949, and the result surprised Mr. Ahmet Ertegun and Mr. Tom Dowd.

“In those days, recording techniques were such that there was a pronounced difference between hearing a live performance in a club and hearing the same song on record,” says Ertegun. Nevertheless, when tape arrived in 1949, a doubting Ertegun told Dowd he wanted to keep the disc cutter active for making back-ups — a request he quickly abandoned after hearing the results of the new medium. Says Dowd, “It was huge. Tape just increased our possibilities.”

「当時の録音技術は、クラブで生演奏を聴くのとレコードで同じ曲を聴くのでは、明らかな違いがあった」とアーティガン氏は言う。とはいえ、1949年に(Ampex 300)テープレコーダが届くと、疑心暗鬼になっていたアーティガン氏は、(Atlantic の録音エンジニアである)トム・ダウド氏に、バックアップとしてディスクカッターを使い続けたいと伝えた。しかし、新メディアによる録音結果を聴いて、アーティガン氏はその訴えをすぐに取り下げた。ダウド氏は言う。「本当に凄かった。テープは我々の可能性を広げてくれたんだ。」

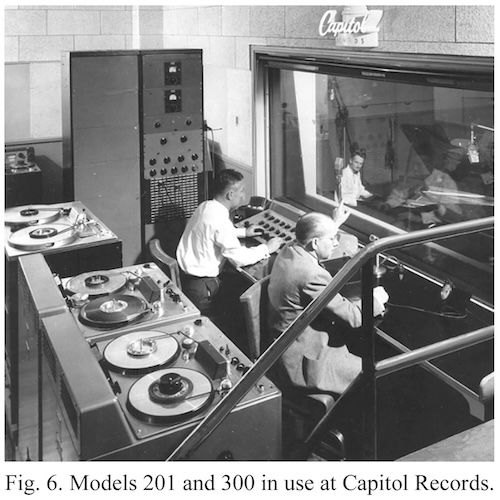

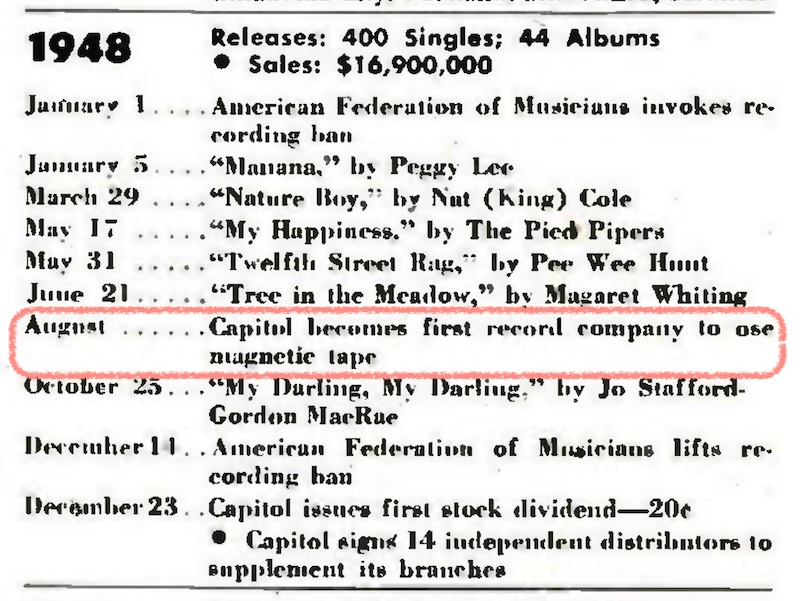

“Studio Stories”, by David Simmons, Backbeat Books, 2004, p.5017.2.2 Capitol Records as the earliest label to adopt Tape Recording

米国のメジャーレーベルの中では、Capitol が最も早くに磁気テープを導入しました。

Capitol was the first to use magnetic tapes in recordings, among the U.S. major labels.

source: “History of The Early Days of Ampex Corporation, as recalled by John Leslie and Ross Snyder”, AES Historical Committee, December 17, 2010.

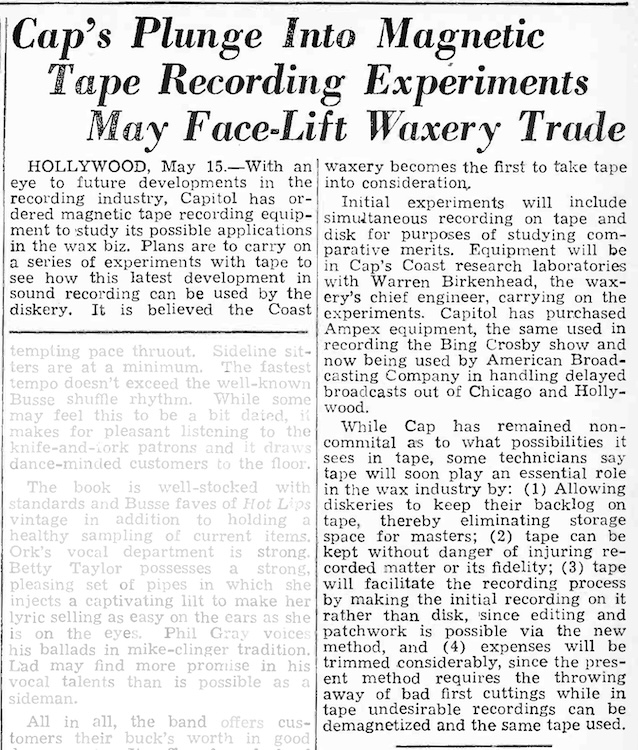

The Billboard 誌 1948年5月22日号には、キャピトルが磁気テープ装置を購入して、ディスク製造にどのように使えるか実験を行う、という記事「Cap’s Plunge Into Magnetic Tape Recording Experiments May Face-Lift Waxery Trade」(Capitol の磁気テープ録音実験参入により、ディスク業界に変革が起こるか)が掲載されています。

May 22 1948 issue of The Billboard features the article entiled “Cap’s Plunge Into Magnetic Tape Recording Experiments May Face-Lift Waxery Trade”.

source: “Cap’s Plunge Into Magnetic Tape Recording Experiments May Face-Lift Waxery Trace”, The Billboard, Vol. 60, No. 21, May 22, 1948, p.27.

HOLLYWOOD, May 15 — With an eye to future developments in the recording industry, Capitol has ordered magnetic tape recording equipment to study its possible applications in the wax biz. Plans are to carry on a series of experiments with tape to see how this latest development in sound recording can be used by the diskery. It is believed the Coast waxery becomes the first to take tape into consideration.

ハリウッド発、5月15日付 — Capitol は、録音業界の将来的な発展を視野に入れ、レコード業界への応用の可能性を探究するため、磁気テープ録音装置を発注した。テープを使って一連の実験を行い、サウンド・レコーディングにおけるこの最新の開発がディスク向上でどのように利用できるか、確認する計画である。西海岸のレコードレーベルである Capitol が磁気テープの活用を考慮する最初のレーベルとなる模様である。

Initial experiments will include simultanous recording on tape and disk for purposes of studying comparative merits. Equipment will be in Cap’s Coast resaerch laboratories with Warren Birkenhead, the waxery’s chief engineer, carrying on the experiments. Capitol has purchased Ampex equipment, the same used in recording the Bing Crosby show and now being used by American Broadcasting Company in hadling delayed broadcasts out of Chicago and Hollywood.

最初の実験では、テープとディスクへの同時録音を行い、その利点を比較検討する予定である。購入された磁気テープ録音装置は、Capitol の西海岸研究所に設置され、レーベルのチーフエンジニアである Warren Birkenhead が実験を担当する。Capitol が購入したのは Ampex 社の機材であり、Bing Crosby Show(ラジオ番組)の録音に使われ、同時に現在 ABC (American Broadcasting Company) 局が遅延放送に使用しているものと同一のものである。

While Cap has remained noncommital as to what possibilities it sees in tape, some technicians say tape will soon play an essential role in the wax industyr by: (1) Allowing diskeries to keep their backlog on tape, thereby eliminating storage space for masters; (2) tape can be kept without danger of injuring recorded matter of its fidelity; (3) tape will facilitate the recording process by making the initial recording on it rather than disk, since editing and patchwork is possible via the new method, and (4) expenses will be trimmed considerably, since the present method requires the throwing away of bad first cuttings while in tape undesirable recordings can be demagnetized and the same tape used.

磁気テープに対してどのような可能性を見出しているか、Capitol は口を閉したままだが、技術者の中には、ディスク業界においてテープが以下のような重要な役割を果たすだろうと言われている。 (1) ディスクメーカがバックログ(未処理分の音源)をテープに残すことができるようになり、マスター(ディスク)の保管スペースが不要になる。 (2) テープは、録音された音源の忠実度を損なう危険なしに保管可能である。 (3) テープは、編集やパッチワークが新しい方法で可能となるため、録音を直接ディスクに行う代わりにテープに行えば、録音プロセスが容易になる。 (4) 現在の方法(ディスク録音)では、カッティングに失敗したディスクを捨てる必要があるが、テープでは望ましくない録音は消磁して同じテープを再利用できるため、経費が大幅に削減可能となる。

“Cap's Plunge Into Magnetic Tape Recording Experiments May Face-Lift Waxery Trade”, The Billboard, Vol. 60, No. 21, May 22, 1948, p.27.そして、その4年後、The Billboard 1952年8月2日号に掲載された「The Capitol Story — A Decade of Growth and Success」でも、1948年8月に他レーベルに先駆けて磁気テープ導入を行った、と記載されています。

Four years later, on August 2, 1952 issue of The Billboard magazine has the feature article “The Capitol Story — A Decade of Growth and Success”, which denotes that Capitol started using magnetic tapes in August 1948.

source: “The Capitol Story – A Decade of Growth and Success”, The Billboard, August 2, 1952, pp.50-51.

17.2.3 Reeves Sound Studios used Fairchild Magnetic Recorders

Wilma Cozart Fine そして C. Robert Fine (1922-1982) 、という、Mercury クラシック録音を代表する両者(ご夫婦)の息子である Tom Fine さんからの情報です。御尊父の C. Robert Fine 氏が働いていた Reeves Sound Studios でも、相当早い時期からテープ録音を使っていたとのことです。

Again, here is another information from Tom Fine-san, son of Wilma Cozart Fine and C. Robert Fine (1922-1982), both of whom represents the legendary Mercury Living Presence recordings. Reeves Sound Studios, where his father C. Robert Fine had worked then, had used magnetic tape recorders since the very early years.

Reeves/Fairchild was early as far as USA studios recording sessions to tape, going back to 1948.

アメリカのスタジオにおける(市販レコード制作用の)メディアとしての磁気テープ使用において、Reeves / Fairchild はかなり早かった。1948年まで遡ると思う。

Capitol was first, with the first Ampex 200A’s. There may have been some outlier small-label productions done using Brush Soundmirror (Model BK-401), but as far as mainstream labels and artists, Capitol was first.

(メジャーレーベルでは)最初期の Ampex 200A を使った Capitol が最も早かった。小規模レーベルでは、Brush Soundmirror (Model BK-401) を使ったりした例があったかもしれないが、メインストリームのレーベルやアーティストに関しては、Capitol が一番早かった。

quoted from the email written by Tom Fine to me (and to Nicholas Bergh) on Jun. 22, 2023.

source: Reeves Sound Studios, NYC (1933-197x), Preservation Sound.

C. Robert Fine (Bob Fine) at the Reeves Sound Studio Studio A Cutting Room,

with Fairchild 523 Cutting Lathe and Fairchild Magnetic Tape Recorder

1949年、Reeves Sound Studio での C. Robert Fine (Bob Fine) 氏の様子。

Fairchild 523 カッティングレースと Fairchild テープレコーダが写っています。

17.2.4 Recording and Mastering, after the introduction of magnetic tape recorders

磁気テープがスタジオに導入されたことにより、新録レコード制作時のプロセスに変化が生じることとなりました。

The introduction of magnetic tape recorders into the studios changed the process during the production of new recordings.

従来は、録音スタジオで演奏された音源が、ラッカー原盤やワックス原盤にそのままカッティングされていました。つまり、今でいうところの「ダイレクトカッティング録音」です。すなわち、録音スタジオのマスタリング機材によって、録音EQカーブが規定されることになります。

Traditionally, sound source was played in a recording studio, and cut directly to lacquer or wax masters, what we now call as “direct-to-disc recordings”. In orhter words, mastering equipments in the studio dictated the recording EQ curve.

screenshot from the movie “The American Epic Sessions” (2017), capturing the recording session in the studio, direct-to-disc recorded with a vintage Scully lathe, cut by Nicholas Bergh.

ドキュメンタリー「The American Epic Sessions」(2017) 中の録音風景。スタジオルームの真横にあるカッティングルームに設置された、フルレストアされた Scully レースでダイレクトカッティング中。エンジニアは Nicholas Bergh 氏。

その後、ラッカー原盤やワックス原盤が、委託するプレス工場(独立系、または大手レーベル所有の工場)に送られ、スタンパー製造や実際のプレスが行われました。

The lacquer/wax masters were then sent to pressing plants (either independent or of major labels) to consign producing stampers and actual discs.

しかし、磁気テープ導入後、録音スタジオとマスタリングスタジオが必ずしも一緒ではなくなります。そのため、録音スタジオもマスタリングスタジオもプレス工場も所有していた大手レーベルはさておき、多くの独立系レーベルは、録音スタジオで収録されたテープを、マイクログルーヴ盤にマスタリング可能なマスタリングスタジオに送り、カッティングしてもらうことになりました。

However, after the introduction of magnetic tapes, recording studios and mastering studios are no longer necessarily located together, although major labels owned recording studios, mastering studios, and pressing plants at once. Therefore, many independent labels did recording sessions at recording studios, then tapes were sent to mastering studios for microgroove cutting.

特に LP や 45回転盤黎明期は、全ての録音スタジオでマイクログルーヴ盤のマスタリング(カッティング)ができたわけではなかったこと、大手レーベルや大手独立系スタジオがマスタリングや製造ノウハウを先行して有していたこと、などがあげられます。

Especially in the very early years of LPs and 45 rpms, not all recording studios were capable of mastering (cutting) microgroove lacquers yet; and major labels as well as major independent studios had the mastering / manufacturing know-how ahead of others.

録音スタジオとマスタリングスタジオが別の場合、当然ですが、録音スタジオではなく、マスタリングスタジオの機材によって録音EQカーブが規定されることになります。

If the recording studio and mastering studio are separate, of course, the recording EQ curve will defined by the mastering studio’s equipments, not those of the recording studio.

本稿で後述する通り、さまざまなパターンがありました。

As will be discussed later in this Pt. 17 article, there were a variety of patterns.

大手レーベルは、録音スタジオ、マスタリングスタジオ、プレス工場の全てを所有していました(場合によっては複数)。

Major labels owned all recording studio, mastering studio, and pressing plant (and in many cases, more than one each).

一方、マイナーレーベルの多くは、独立系録音スタジオなどで収録させてもらい、マスタリングやプレスを外部に委託していました。その際、マスタリングとプレスを大手レーベルに委託するケースも、独立系マスタリングスタジオに委託してそののちプレス工場で製造してもらうケースもありました。

On the other hand, many minor labels had their recordings made at independent recording studios, etc., and outsourced mastering and pressing to outside companies. In some cases, the mastering and pressing were outsourced to major labels, while in others, the mastering was outsourced to inpdenendent studios and then manufactured at the pressing plant.

もちろん、独立系スタジオの中には、録音スタジオそしてマスタリングスタジオを兼ね備えており、プレスのみ外部委託するケースもありました。

Of course, some independent studios had both recording / mastering facilities, and only the pressing was outsourced.

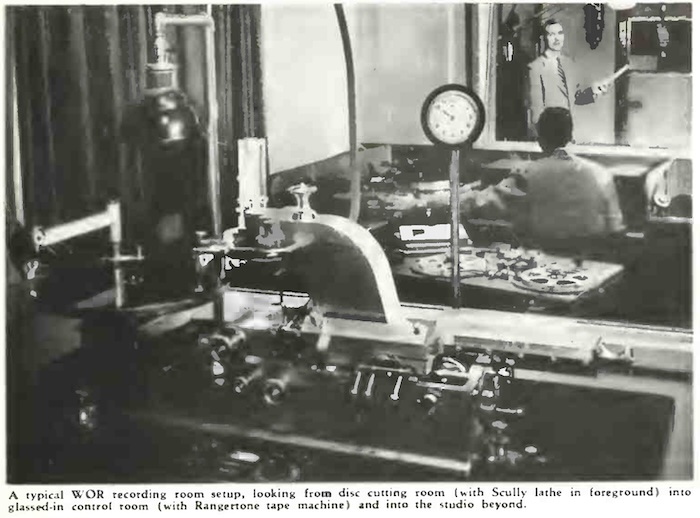

source: “A World Of Recording at WOR”, Audio Record, Vol. 8, No. 2, February 1952, p. 3.

1952年の WOR スタジオをとらえた写真。一番奥が収録スタジオ、真ん中がコントロールルームでテープ録音中、手前がカッティングルーム。

looking from disc cutting room (with Scully lathe in foreground) into glassed-in control room (with Rangertone tape machine) and into the studio beyond.

では、そういったマスタリングスタジオは、各レーベルの個々のリクエストに応じて、録音特性(録音EQカーブ)をその都度変更していたのでしょうか?

So, did those mastering studios changed the recording characteristics (recording EQ curves) each time, according to the individual requests of each label?

おそらくそうではなかったのだろう(基本的には各スタジオはその時点で採用していた固定EQを使っていたのであろう)と考えています。この話は本稿 Pt. 17、およびシリーズ全体に通底する仮説となります。

I belive that this was probably not the case (basically, each studio was using the fixed EQ they employed at the point in time). This will be my hypothesis that runs throughout this Part 17 and the entire series of my article.

もちろん、あくまで仮説ですので、クライアントごとに録音特性を変更したスタジオの存在を証明する資料があれば、ぜひそれを見つけ出したいものです。

Of course, this is just a hypothesis (and my two cents), if there is some documentation that proves the existence of a studio that changed the recording characteristics for each client, I would love to find it.

17.3 Reeves Sound Studios as of 1949 / Fine Sound Studios as of 1952

1933年にオープンし、Fairchild 社と非常に懇意であった Reeves Sound Studios。商用録音や放送局トランスクリプション盤制作の他にも、主として映画用音声録音を行っていた、このスタジオに関する技術詳細は、1949年の FM and TV 誌に掲載されたという解説記事「Design of Recording Systems, Pts. 1-3 (by Leon A. Wortman)」にて非常に詳しく解説されており、必読です。

Opened in 1933, Reeves Sound Studio (primarily used for film sound recordings as well as commercial recordings and radio transcriptions) had shared close relationship with the Fairchild company. Technical details of this particular studio are described in great detail in the article “Design of Recording Systems, Pts. 1-3” (by Leon A. Wortman), which appeared in the FM and TV magazine in 1949. It’s such an incredible “must-read” article.

1949年〜1953年の技術面から見た状況を理解する上でも参考になるであろう、 1949年当時の Reeves Sound Studios に関する解説記事を、詳しく読み解いていきましょう。

Now we’re going to read the details of the article, which describes the technical details at the Reeves Sound Studios as of the year 1949. I belive this will definitely help understand the technical aspects in the industry, during the pre-RIAA LP era (from 1949 to 1953).

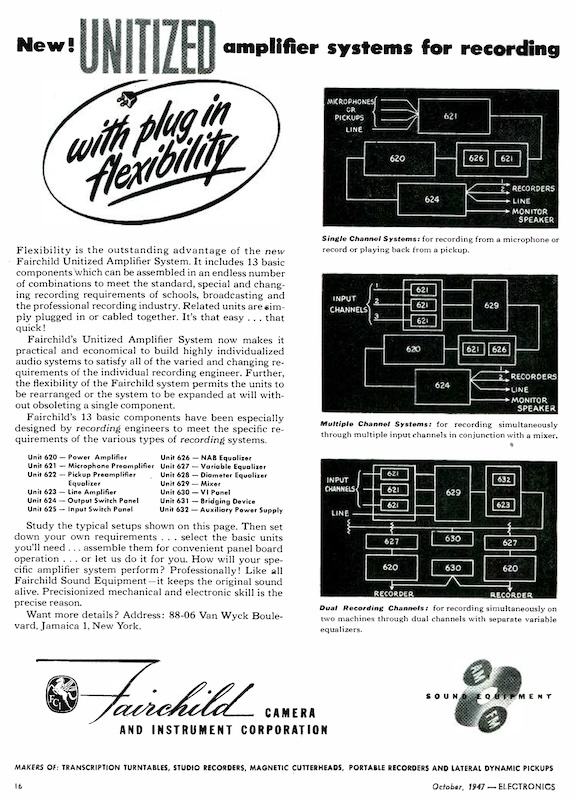

執筆者は Fairchild Recording Equipment 社の Technical Data 部門に所属していた Leon A. Wortman 氏で(本稿 Pt.12 セクション 12.2.1 のコラム にも登場します)、この記事は FM and TV 誌に2号連続で掲載された後、Fairchild 社のプロモーション用にブックレットにまとめられたものだそうです。スタジオで使用されている機材の詳細や、1949年暮れ当時の録音チェーンなどが詳しく解説されています。

The author is Leon A. Wortman, Tehnical Data Division, Fairchild Recording Equipment Corporation (his name already appears at Pt.12 Section 12.2.1’s column). Wortman’s article was initially published in two consecutive issues of the FM and TV magazine , then recompiled into a booklet for Fairchild’s promotional purposes. It details the equipment used in the studio and the recording chain at the end of 1949.

もちろん、のちに Fine Sound Studios 〜 Fine Recordings で活躍し Mercury Living Presence の一連の仕事で有名となる、チーフエンジニアの C. Robert Fine 氏やその右腕 のカッティングエンジニア George Piros 氏も登場します。ちなみに、この時期の Mercury はまだ、45回転盤への参入はしていませんでした。

Of course, this article features the chief engineer C. Robert Fine and his colleague (cutting engineer) George Piros. Both would later leave Reeves and establish Fine Sound Studios then Fine Recordings, known for the legendary Mercury Living Presence recordings. Incidentally, Mercury had not yet entered the 45 rpm market at this time.

Part 1 は、Reeves Sound Studios で使われている技術などの全般的な解説。Part 2 は、商用録音(市販レコード向け)の録音チェーンの詳細な解説。Part 3 は、スタジオA(TVや映画フィルム用)〜スタジオB(一般的なスタジオ録音)〜スタジオC(ミキシング用、およびフィルム制作用)のより詳しい解説、となっています。

Part 1 of the Worman article features the general overview of the technology and equipment used at the Reeves Sound Studios in 1949; Part 2 describing details of the recording chain for commercial recordings (i.e. phonograph records, etc.); Part 3 featuring the extended overview of the entire studio, including Studio A (for TV and movie film recordings), Studio B (for regular studio recordings) and Studio C (for mixing or film making).

17.3.1 All the Mercury releases around 1949 were cut at the Reeves Sound Studios

例えば Part 3「A description of The Reeves Sound Studios installation, the concluding Discussion of Unitized Equipment」では、1949年当時の Mercury 盤はReeves Sound Studios でカッティングされていたと解説があります。

For example, Part 3 “A description of The Reeves Sound Studios installation, the concluding Discussion of Unitized Equipment” describes that all Mercury records as of 1949 were mastered (cut) at the Reeves Sound Studios.

Standard and long-playing Mercury records are produced in the Reeves plant. Every Mercury record label is marked Reeves-Fairchild Margin Control. These words indicate that full dynamic range is obtained through the use of the instantaneous variable-pitch recorder described in Part 2 of this series.

Mercury レーベルの従来の(78回転)盤、および長時間(LP)盤は、Reeves スタジオで制作されている。Mercury 盤(LP)のレーベルには例外なく「Reeves-Fairchild Margin Control」と記されている。これは、本解説 Part 2 で説明した、即時バリアブルピッチ方式のディスクレコーダの使用により、フルダイナミックレンジが得られていることを示している。

(from my collection)

Limiting factors of dynamic range have been the high basic noise level of record pressings which masks pianissimo passages, and the danger of overcutting of full forte passages. Before the perfection of vinylite pressing, it was necessary to cut all sound at maximum level to override the high basic noise of shellac-composition pressings.

ダイナミックレンジを制限する要因は、ピアニッシモのパッセージを聞こえなくしてしまう、レコード盤由来の基本ノイズレベルと、フルフォルテのパッセージでオーバーカッティングしてしまう危険性である。ヴィニライト盤が完成する以前は、シェラック化合物で製造されたレコード盤のノイズに対応すべく、記録する音を可能な限り最大レベルでカッティングする必要があった。

However, now that the basic noise has been so greatly reduced, the recording studios have gone all out for life-like dynamic range. Records cut in this way are beautiful to hear, from pianissimo passages are no longer lost in background noise and, by varying the cutting pitch, to avoid overcutting as the signal level increases, a full dynamic range can be achieved.

しかし(ヴィニライト盤の登場により)このノイズの問題から解放された現在では、録音スタジオでは生命感あふれるダイナミックレンジを徹底的に追求するようになった。この方法でカットされたレコードは、ピアニッシモのパッセージがバックグラウンドノイズで失われることがなくなり、また、信号レベルが上がるにつれてカッティングピッチを変化させ、オーバーカッティングを避けることで、フルダイナミックレンジが実現可能となった。

“Design of Recording Systems, Part 3”, Leon A. WortmanBroadcast Telecasting 誌 1950年1月23日号 (Vol. 38, No. 4) p.45 に、Fairchild Equipment Corporation の広告が掲載されているのですが、Reeves Sound Studios のカッティングエンジニア George Piros 氏が Fairchild 523 で可変ピッチのノブを操作しながらカッティングする写真が掲載されています。

On page 45 of the Vol. 38, No. 4 (January 23, 1950) issue of the Broadcast Telecasting Magazine has the interesting ad by Fairchild Equipment Corporation: George Piros, a cutting engineer at the Reeves Sound Studios at the time, was operating the Fairchild Studio Recorder Unit 523, instantaneously adjusting the groove pitch while recording the lacquer disk.

source: Fairchild ad, Broadcasting Telecasting, Vol. 38, No. 4, January 23, 1950, p.45.

17.3.2 Ormandy & Philadelphia Philharmonic at Reeves Sound Studios on May 10, 1949

同じく Part 3 には、Eugene Ormandy 指揮、Philadelphia Philharmonic Orchestra の THOMPSON: Louisiana Story レコーディング中の写真が掲載されています。

In the same Part 3 of the Mortman’s article, the photo of the session at Studio B by Philadelphia Philharmonic Orchestra, Eugene Ormandy conducting, recording “THOMPSON: Louisiana Story” is featured.

For example, the photograph of the Philadelphia Philharmonic Orchestra, Fig. 1, was taken during the actual recording of the musical score for “Luuisiana Story.” Disc and tape recording was done on channel B equipment, and played back for the director’s approval.

例えば、Fig. 1 として掲載したフィラデルフィア管弦楽団の写真は、(1948年に公開された白黒フィルムドラマの)「Louisiana Story」のためのスコアを実際に録音中に撮影されたものである。(Fig. 6 に掲載したブロックダイアグラムにおける)チャンネル B の機材でディスク録音およびテープ録音が行われたのち、ディレクタの許可の元プレイバックが行われた。

“Design of Recording Systems, Part 3”, Leon A. Wortman

source: Reeves Sound Studios, NYC (1933-197x), Preservation Sound (original source: Tom Fine).

Eugene Ormandy conducting Philadelphia Philharmonic Orchestra, performing “Louisiana Story” at Reeves Sound Studio B

Reeves Sound Studio B で “Louisiana Story” をレコーディング中の Ormandy: Philadelphia 管弦楽団

各種 ディスコグラフィー を参照すると、この組み合わせは、1949年5月10日に録音された Columbia レーベル用のもので、Columbia Masterworks ML-2087 (10インチLP)として1950年にリリースされた音源のようです。

According to the discography information, this recording session was executed on May 10, 1949 for Columbia label, which would be released as Columbia Masterworks ML-2087 (10-inch LP) in 1950.

記事中では「チャンネル B の機材でディスク録音およびテープ録音が行われた」と書かれていましたが、ML-2087 のデッドワックスを確認したところ、Reeves Sound Studios 由来のマトリクスは存在しておらず、当時の Columbia Masterworks 10インチLP と全く同じ特徴の刻印しかなかったので、Reeves Sound Studio B で録音されたテープが Columbia に送られ、Columbia のスタジオでラッカーカッティングされたはず、と推定できます。

In the Wortman’s article, there is a paragraph “disc and tape recording was done on channel B equipment”. However, by inspecting the actual copy of ML-2087 and its deadwax information, no matrix derived from Reeves Sound Studios is there: only the ordinary matrix that is common among Columbia Masterworks 10-inch LPs. So I can say that the tape was recorded at Reeves Sound Studio B, then sent to the Columbia Studio, then the lacquer was cut by a Columbia’s engineer.

Columbia Masterworks ML-2087 Side-A

with Matrix stamp of “LP 1746” and “3B”, denoting Columbia’s own mastering

“LP 1746” というマトリクスから、Columbia 自社マスタリングと解釈できる

17.3.3 Reeves Sound Studios in 1949 using the NAB curve for commercial records as well

また、Part 1 “A Discussion of the Principles of Design” (録音スタジオ設計原則の解説) および Part 2 “A Detailed Description of a Commercial Recording Studio Composed Entirely of Unitized Audio Equipment” (ユニット化された機器のみで構成された、商用録音スタジオの詳細説明) では、Reeves Sound Studios の録音チェーンの詳細について解説が行われています。

Also in the Wortman’s article, namely in Part 1 “A Discussion of the Principles of Design” and Part 2 “A Detailed Description of a Commercial Recording Studio Composed Entirely of Unitized Audio Equipment”, details of the entire chain of the Reeves Sound Studio was described.

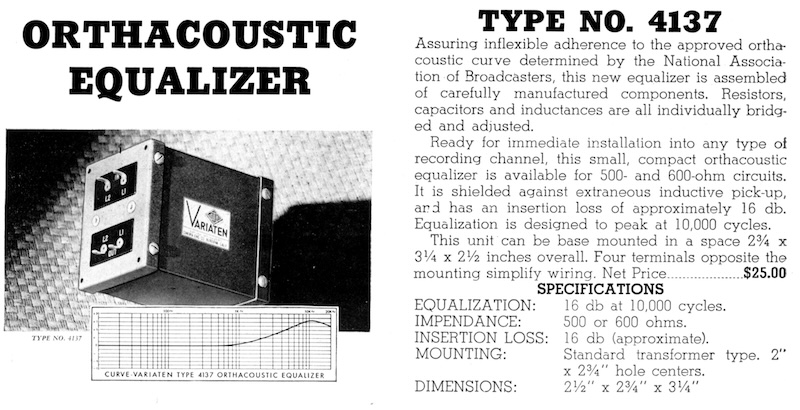

興味深いのは、1949年当時 Reeves スタジオでは、トランスクリプション盤用と市販盤用の両方において、ディスクカッティングにはパッシブ方式の NAB 録音規格イコライザを使っていた、と読めそうな記載です。まず、Part 1 では、NAB 録音再生規格についての簡潔な説明があります。

Interestingly enough, the description can be interpreted as: “passive NAB recording equalizer was used both for cutting transcriptions and commercial records”. Part 1 briefly explains the NAB Recording and Reproducing Standards.

The NAB Recording and Reproducing Standards Committee proposed that, in order to produce disks with a high signal level above the inherent noise, the frequencies above approximately 1,000 cycles have a rising characteristic. It was proposed that a 10,000 cycle signal be 16 db higher than a 1,000 cycle signal. With the adoption of this standard, it was possible to design a simple and inexpensive equalizer that can be inserted in the audio line to produce this characteristic curve automatically.

NAB 録音・再生標準規格委員会は、(ディスクの)固有ノイズを上回る高い信号レベルのディスクを製造するために、約 1,000Hz 以上の周波数帯域を持ち上げる記録特性を提案した。10,000Hz においては 1,000Hz の記録レベルに比べて +16dB となる特性である。この規格が採用されたことで、NAB録音特性カーブを自動的に生み出すシンプルで安価なイコライザを設計することが可能となり、録音チェーンに挿入するだけでよくなった。

(…snip…) An NAB equalizer, inserted ahead of the power amplifier, meets this standard. The equalizer can be quite compat, mounting in a rack panel space as small as 1 3/4 in. A switch is needed to permit instantaneous insertion and removal of the equalizer from the electrical circuit. Passive equalizers neccesitate insertion losses. If the insertion loss cannot be tolerated, an additional booster amplifier is required.

(…中略…) パワーアンプの前段に挿入される NAB 録音イコライザは、この標準規格を満たしている。このイコライザは非常にコンパクトにでき、1 3/4インチ(約44.5mm) のラックスペースにマウント可能である。また、このイコライザを即座に電気回路(録音チェーン)から除去、または挿入するためのスイッチが必要となる。ところで、パッシブ方式のイコライザでは挿入損失が生じるため、この損失が許容範囲を超える場合には、別途ブースターアンプの追加が必要となる。

“Design of Recording Systems, Part 1: “A Discussion of the Principles of Design””, Leon A. Wortmanそして Part 2 では、商用録音スタジオの詳細説明がなされていますが、ここでも NAB 録音イコライザと自動補正イコライザが使われている旨記載があります。少なくとも1949年時点では、レコーディングを委託されたレーベルごとにカッティング時の録音カーブを変更することなく、すべて NAB カーブに統一されていた、という可能性が高そうです。

Then the Part 2 of the Wortman’s article describes technical details of the studio for commercial recordings. Again, NAB recording equalzier was mentioned. So it could be highly possible that the Reeves (as of 1949) used NAB Recording Characteristics for any labels, rather than using different EQ curves for each label.

Automatic diameter equalizers and NAB equalizers are incorporated in the system, with in-out switching brought to a convenient panel on the cutting room rack.

(カッティング径にあわせた)自動補正イコライザと NAB イコライザがシステムに統合されており、カッティング室のラックにイン/アウトスイッチのついたパネルが設置されている。

“Design of Recording Systems, Part 2: “Detailed Description of a Commercial Recording Studio””, Leon A. Wortmanそういえば、最初期(1949年)の Mercury ポピュラー盤 LP は、のちの CD 復刻音源などの帯域バランスと比較すると、NAB カーブや Columbia LP カーブの方がしっくりくる盤があります。

By the way, I have several Mercury Popular LPs from very early years (1949), which sounds better with NAB curve or Columbia LP curve. This can be confirmed with the comparing with the sounds of later CD / digital reissues.

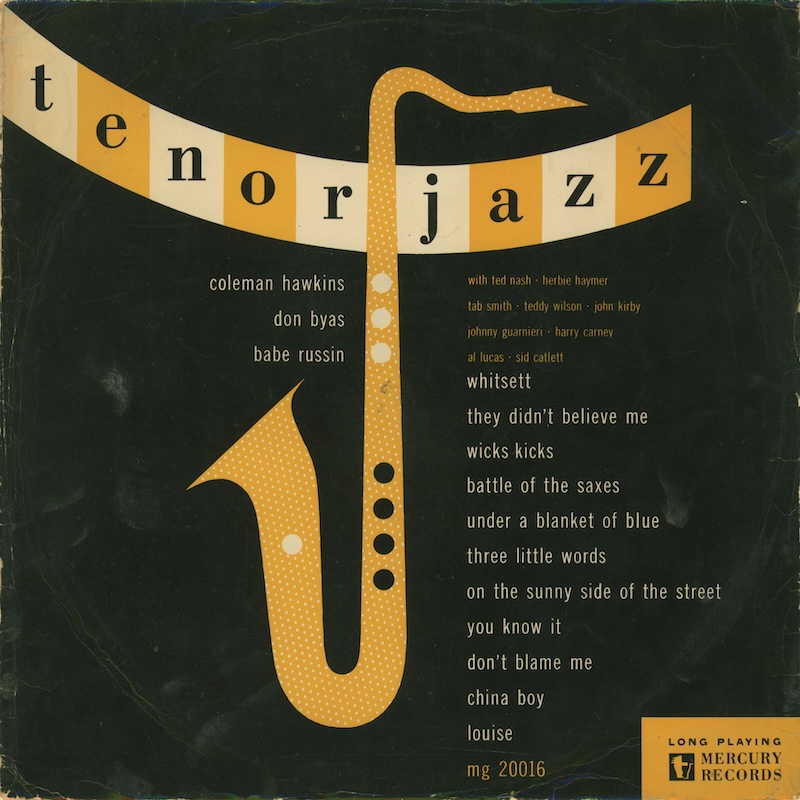

例えば手元の盤ですと、MG-20016 “Tenor Jazz” は、78回転盤時代としては非常に良好な音質で知られる Keynote レーベルのコンピレーションです。重量ヴィニライトプレス盤でペラジャケの最初期パターンです。

Here is Mercury MG-20016 “Tenor Jazz” for example. This LP is a compilation of Keynote label’s Jazz performances, which were originally recorded in the mid-1940s, which sounds very nice as the recordings from the late 78 rpm era. The copy I own is a heavy vinylite disc, glossy black/gold label, enclosed in a thin paper sleeve jacket.

本盤は、AES標準再生カーブや RIAA カーブによる再生だと高域がキンキンして聴こえます。後年 RIAA でリカッティングされた EmArcy 盤や後年の CD リイシューと比較しても、NAB カーブでの再生の方がフラットなのでは、と感じます。(聴感のみによる判断は全く客観的でないことに注意)

If I play this LP with RIAA or AES curve, it will sound too bright in the high frequency region, compared with the sound of EmArcy LPs (recut with RIAA) and later CD reissues. So I guess the NAB curve was used for mastering this particular LP (please note this is just my subjective opinion).

残念ながら、1949年当時の裏ジャケットには推奨再生カーブの記載もなく(リリースカタログのみ記載)、当時のスタジオの詳細な技術メモが残っているわけでもありませんので、あくまで仮説でしかありませんが。1951年に AES 標準再生カーブが発表・推奨される前、最初期の Merucry LP は NAB カーブ (つまり Columbia LP カーブに非常に近い) でカッティングされていた時期があった可能性も考えられます。

Unfortunately, this thin paper sleeve jacket for this particular LP (made in 1949 or 1950) has no mention about recommended reproducing characteristics: only a list of many Mercury LP releases is printed on the back side. Also, I don’t think any technical memo / documentation survive to describe how this particular LP was mastered from original Keynote masters. Anyway, Reeves Sound Studios might have used NAB recording characteristics (i.e. very close to Columbia LP’s characteristics) for mastering (cutting) commercial records, at least in the year 1949.

1948年に LP を最初に出したのは Columbia であり、その Columbia が Columbia LP カーブを使っており、AES 標準再生カーブが提唱されるまでは、他レーベルがその Columbia LP カーブに寄せるのは自然なことだと考えられるからです。

I guess so because: LP was originally unleashed by Columbia in 1948; Columbia used Columbia LP curve; and it was natural for many labels to mimic Columbia LP’s characteristics, until the AES Standard Playback Curve was published.

Tom Fine さんも以下のようにコメントしてくれましたが、同時に補足として、1951年1月に AES 再生カーブが発表される前から、Reeves で C. Robert Fine 氏や George Piros 氏が AES 相当の録音カーブを使っていた可能性も指摘していました。

Tom Fine-san also sent me a comment like this (please note, at the same time, he also pointed out that there is still a possibility that his father C.R. Fine and George Piros at Reeves might have used the AES curve BEFORE the AES Standard Curve was published in January 1951).

I think my father used the AES curve in the early 50s, if it was published. Very early Mercury LPs may have used Columbia’s original curve. Those would have been cut at Reeves.

1950年代初頭、AES再生カーブの仕様が公になってから、父 (C.R. Fine) は AES標準再生カーブに対応する録音カーブを使っていたと思う。Reeves でカッティングされた頃の超最初期の Mercury LP は、恐らく Columbia カーブを使っていたのだろう。

quoted from the email written by Tom Fine to me (and to Nicholas Bergh) on Jun. 28, 2023.さらに、ラッカー原盤や録音テープの製造メーカ Audio Devices Inc. の発行する業界誌 Audio Record 誌 に掲載された C.J. LeBel 氏の連載記事 “Disc-Data for the Recordist” において、マイクログルーヴLPの技術特性を解説する1949年2月号掲載の回では、「LP カッティング用にトランスクリプション用 NAB 録音カーブを使うことも可能」と書かれています。

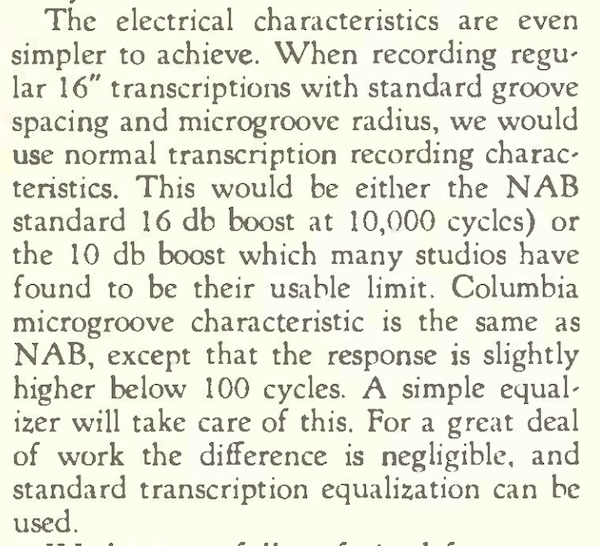

Here’s another interesting article, this time in the Audio Record trade magazines published by Audio Devices Inc. (maker of lacquer discs and magnetic tapes for professionals), from Vice President C.J. LeBel’s serial article “Disc-Data for the Recordist”. Technical details of microgroove LPs are featured on Feb. 1949 article, where he notes as “standard transcription equalization can be used (for commercial microgroove recordings, as a replacement of Columbia’s LP curve)”.

source: “Disc-Data for the Recordist: Microgroove In Your Studio Part 2, Equipment Requirements”, Audio Record, Vol. 5, No. 2, February 1949, p.3.

The electrical characteristics are even simpler to achieve. When recording regular 16″ transcriptions with standard groove spacing and microgroove radius, we would use normal transcription recording characteristics. This would be either the NAB standard (16 db boost at 10,000 cycles) or the 10 db boost which many studios have found to be their usable limit. Columbia microgroove characteristic is the same as NAB, except that the response is slightly higher below 100 cycles. A simple equalizer will take care of this. For a great deal of work the difference is negligible, and standard transcription equalization can be used.

(マイクログルーヴLPカッティング用の)電気的特性は更に簡単である。標準的なピッチで16インチトランスクリプション盤にマイクログルーヴでカッティングする場合は、通常のトランスクリプション盤用の録音特性を使用する。これは、10,000Hz で 16dB のブーストという NAB 標準規格、あるいは、多くのスタジオが使用可能な限界とみなしている 10dB ブーストのいずれかとなる。ちなみに Columbia 社のマイクログルーヴ LP の録音特性は、ほぼ NAB 特性と同じであるが、100Hz 以下のレスポンスが NAB に比べてわずかに高くなる。この差分は簡単なイコライザを使うことで対処可能である。また、ほとんどの録音においては、NAB と Columbia LP の差は無視できるほど小さいので、トランスクリプション盤カッティングで使用している録音イコライザをそのまま使用しても差し支えないだろう。

“Disc-Data for the Recordist: Microgroove In Your Studio Part 2, Equipment Requirements”, by C.J. LeBel, Vice President, AUDIO DEVICES, Inc. Audio Record, Vol. 5, No. 2, February 1949, p.3ですので、自らラッカーカッティングしていた独立系スタジオでは、Columbia LP 録音カーブの代用として NAB 録音カーブ用固定イコライザを使い、ラッカーカッティングをしていたのかもしれませんね。

So, this may suggest that many independent studios might have used the NAB recording characteristics as a substitute for Columbia LP recording characteristics.

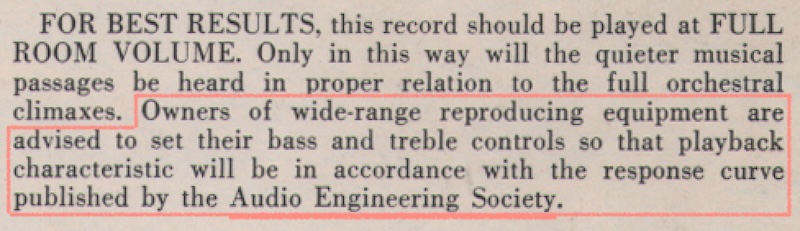

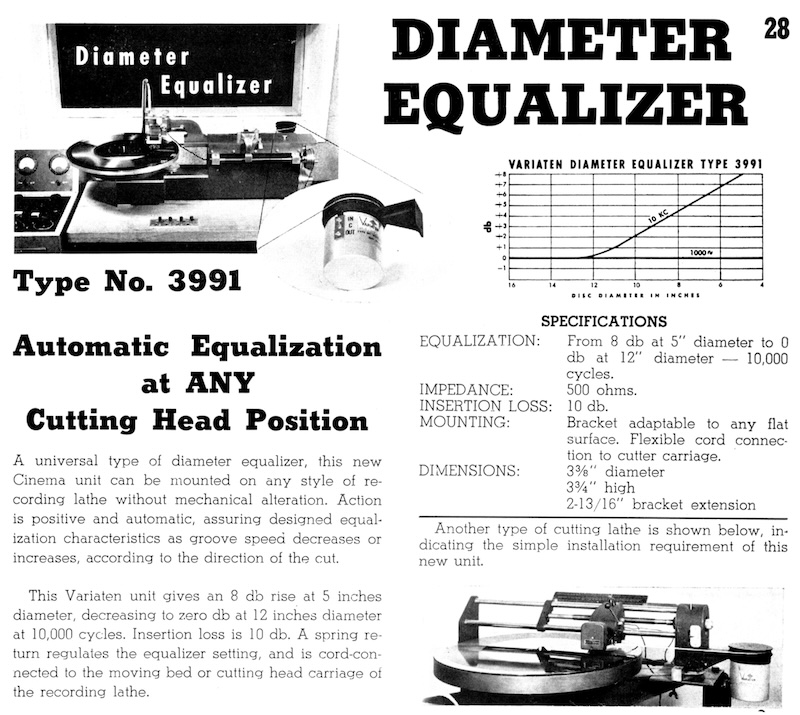

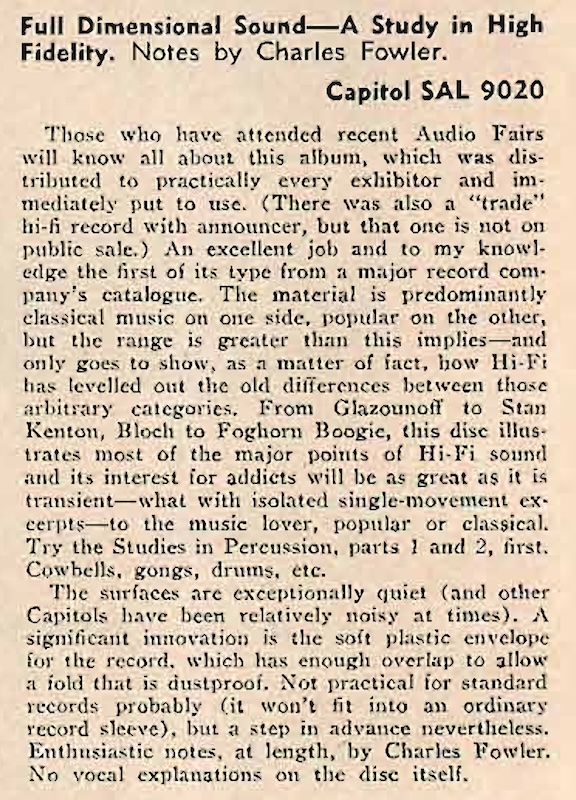

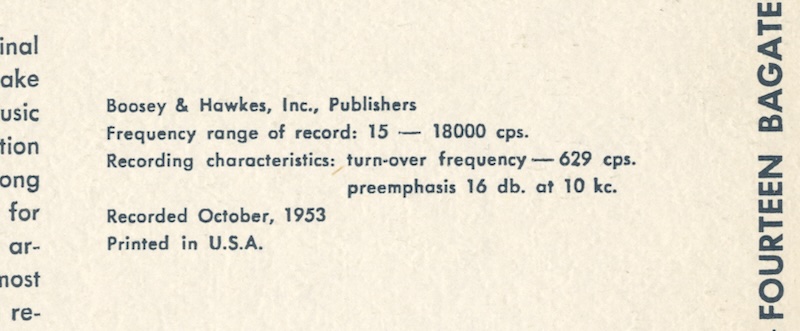

余談ですが、Mercury Living Presence (Mercury Classics Olympian Series) の初録音、1951年4月23〜24日にシカゴのオーケストラホールで Ampex テープレコーダで記録された、Rafael Kubelik 指揮、Chicago Symphony Orchestra の “Pictures At An Exhibition” (Mercury MG-50000) は、Fine Sound Inc. 独立前、まだ Reeves Sound Studios チーフエンジニアだった C. Robert Fine 氏が録音を担当、Reeves Sound Studios のカッティングエンジニア George Piros 氏によりカッティングが行われました。

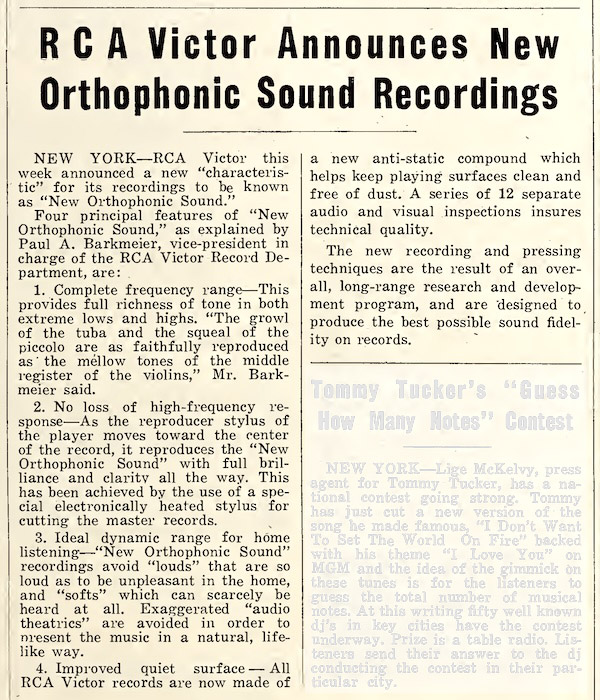

As a side story, the very first recording of Mercury Living Presence (Mercury Classics Olympian Series) was “Pictures At An Exhibition” (Mercury MG-50000), Chicago Symphony Orchestra, Rafael Kubelik conducting, recorded at Chicago’s Orchestra Hall on April 23-24, 1951. The recording engineer was C. Robert Fine, still during his career with Reeves Sound Studios (one year before he went out on his own Fine Sound Inc.), with George Piros as a mastering (cutting) engineer.

この1951年中頃の時期ですでに、記録特性を AES 標準再生カーブにあわせたものに変更されていることが、ジャケット裏の記載から読み解けます。

According to the liner-notes on the back cover, recording characteristics was the one that corresponded to the AES Standard Playback Curve.

“About This Recording…” section of Mercury MG-50000 (1951), recommending AES playback curve.

Mercury MG-50000 (1951) の裏ジャケより。AES 再生カーブが指定されている。

photo courtesy of Monte Fullmer-san

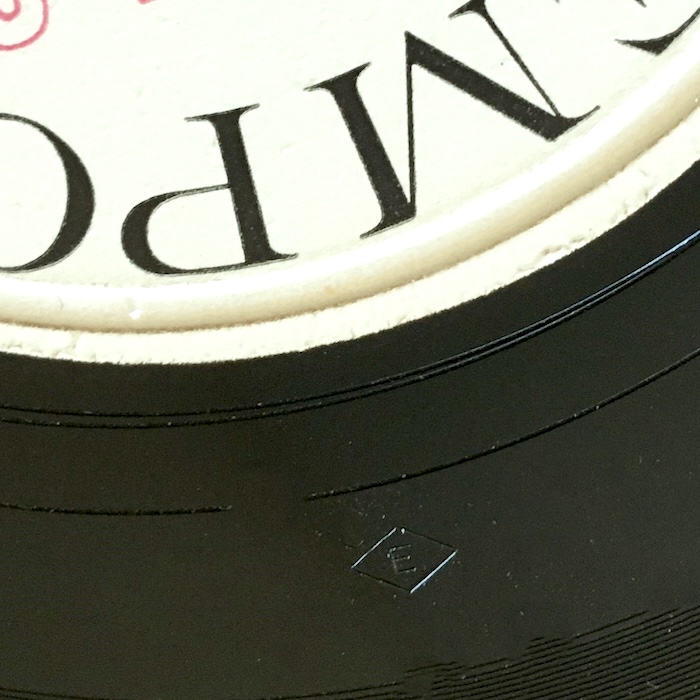

possibly the first variation of MG-50000: black/silver label with “Reeves-Fairchild Thermodynamic Margin Control”

MG-50000 のおそらく最初期のレーベル

1951年当時の Reeves Sound Studios で、録音用イコライザは NAB のままで、前段にEQ回路を追加して AES 相当に補正してカッティングしたのか、それとも盤(やレーベル)ごとに AES / NAB イコライザを切り替えてカッティングしたのか、正確なところは分かりません。

It is not known if the Reeves Sound Studios in 1951 used NAB recording equalizer unit with additional EQ networks to meet the AES curve, or different recording EQ units like NAB or AES were switched and used for recording (and for labels).

一方、1951年当時は、放送局用録音再生機格として 1949 NAB はまだ有効でしたから、当時の Reeves では放送局トランスクリプション用の機材と、市販用レコード用の機材とを分けて運用していたのかもしれません。

On the other hand, 1949 NAB Recording and Reproducing Standards was still valid in the broadcasting industry, so it could be that Reeves Sound Studios had two distinctive systems, one for electrical transcriptions, the other for commercial records.

1951年当時の Reeves Sound Studios の録音チェーンを解説する記事や資料を見つけられていませんので、あくまで推測でしかありませんが。

Please note that this is just my guess, because I cannot find any articles nor documentation that describe Reeves’ recording chain in 1951.

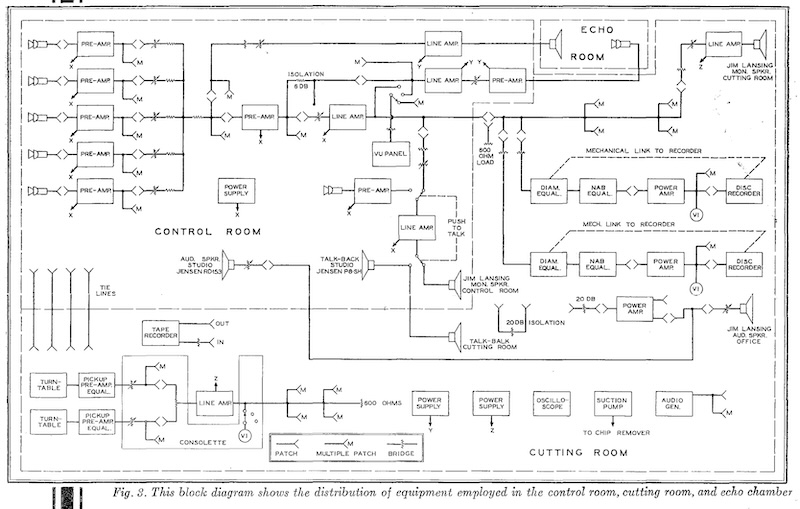

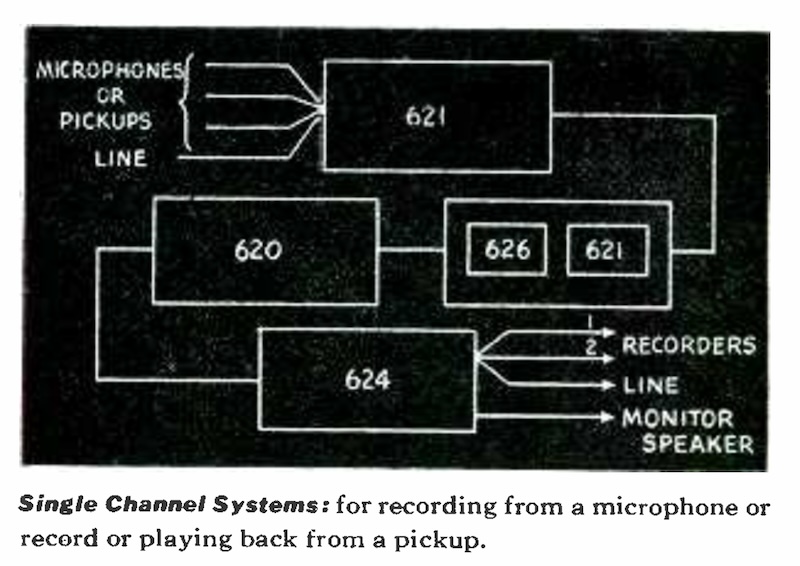

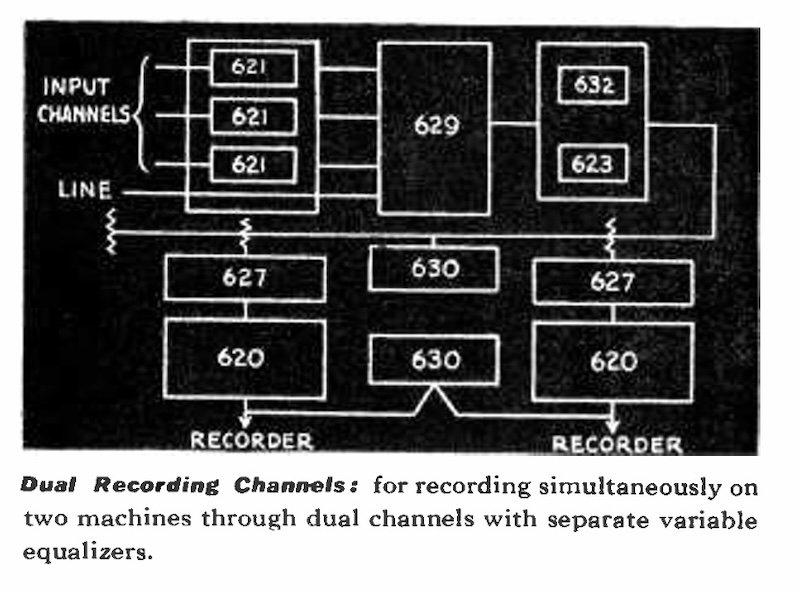

さて、同記事に戻ると、1949年当時の Reeves Sound Studios のシステム全体(コントロール室、カッティング室、エコーチェンバー)のダイアグラムが掲載されています。

Back to the Wortman’s article. It has a block diagram of the Reeves Sound Studio facilities (control room, cutting room, echo room, etc).

“Design of Recording Systems Part 2”, by Leon W. Wortman, 1949.

1949年当時の Reeves Sound Studios の市販レコード用全機材のブロックダイアグラム。コントロール室〜エコーチェンバー〜カッティング室。

カッティングレース近辺を拡大してみると、「Diameter Equalizer」「NAB Equalizer」「Power Amplifier」と順に接続されていることが分かります。最初の「Diameter Equalizer」は、ホットスタイラス方式が実用化されていなかった当時、線速度が落ちるラッカー盤中心に近づくにつれ高域補正を強めるための、録音自動補正イコライザです。

Close-up view near the disc recorders (cutting lathes) shows such recording chain: “Diameter Equalizer”, “NAB Equalizer” and “Power Amplifier” in line. The “diameter equalizer” was an automatic equalizer to adding the high frequency boost as the cutter goes to the inner diameter, when “Hot Stylus” technique was not widely practicalized.

source: “Design of Recording Systems Part 2”, by Leon W. Wortman, 1949.

カッターヘッドが中心に近づくにつれ高域補正を強める自動補正回路が、NAB録音イコライザの前段に接続されている

この 自動補正イコライザ (Diameter Equalizer) は、放送局用トランスクリプション盤(16インチ 33 1/3回転)の頃から LP 黎明期まで使われていました。

Such diameter equalizers had been frequently used in the studios, from the electrical transcription years (1930s) to early LP years.

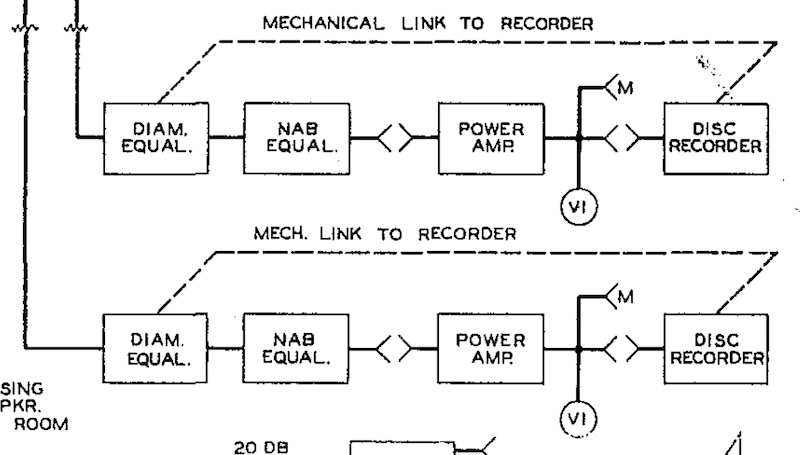

例えば RCA は、放送局用ラッカーカッティング機材用に、同様の自動補正イコライザとして「Automatic Recording Equalizer」を提供しており、1940年時点で MI-4894、その後 MI-11100 / 11101 をラインアップしていました。

For example, RCA manufactured its own “Automatic Recording Equalizer” MI-4894 (as of 1940) and MI-11100 / 11101 from the mid-1940s, for instantaneous transcription recordings.

source: RCA Broadcast Audio Equipment, 1948, p.82

RCA 73-B および 72-D / 72-DX 用の、録音自動補正イコライザ

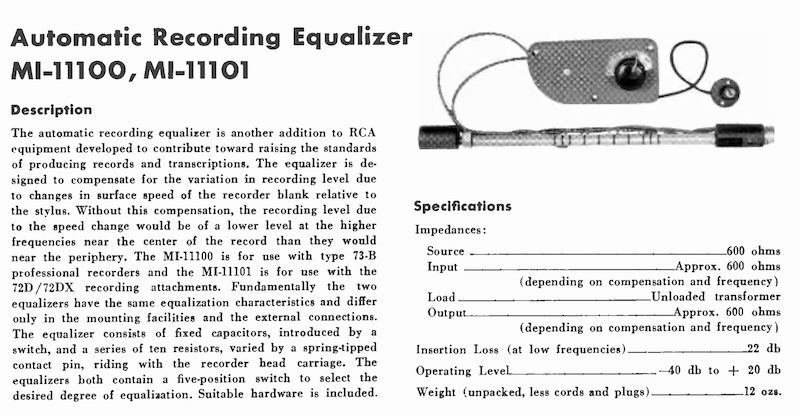

他にも、西海岸 Cinema Engineering 社の機材も当時の録音スタジオで広く使われていましたが、同社も Type No. 3991 Diameter Equalizer をラインアップしていました。スピンドルから12インチ離れた位置でのカッティングでは補正なしで、内側に進むに従って高域補正が強まり、半径5インチでは +8dB (10,000Hz) もブーストしてカッティングされていました。当時のカッター針では、線速度が落ちれば高域記録が弱くなるので、これでちょうどいい感じにカッティングできる、という仕組みです。

Also Cinema Engineering offered its own Type No. 3991 Diameter Equalizer. with zero db at 12 inches diameter, increasing to 8 db boost at 5 diameter at 10,000 cycles. Cutting heads before the advent of “Hot Stylus technique” could not record enough high frequency modulation as the linear velocity decreases, so such “diameter equalizer” was used to compensate the high frequency loss.

source: Cinema Engineering Company Catalog No. 10 (possibly in 1950?)

1950年前後に発行されたと思われる Cinema Engineering 社のカタログに掲載された Diameter Equalizer

ちなみに、Fairchild の自動補正イコライザは Fairchild Unit 628 Diameter Equalizer という型番でした。残念ながら、Fairchild 628 の写真や資料は見つけられませんでした。

Fairchild’s version was Fairchild Unit 628 Diameter Equalizer, although I could not find any photo or documentation of it so far, unfortunately.

1949年当時の Reeves Sound Studios では、この録音自動補正イコライザを市販LPのカッティングにも使っていたことが伺えます。そして、線速度が落ちても高域記録特性が十分に保てる「ホットスタイラス方式」(Pt. 12 セクション 12.2.2.1 を参照)が一般的になるまでは、多くのカッティングスタジオで同じように使われていたものと思われます。

So in 1949, Reeves Sound Studios used the 628 Diameter Equalizer for commercial LP mastering as well. Also, many mastering studios at the time had used similar automatic equalizers, until the “Hot Stylus” technique (see: Pt. 12 Section 12.2.2.1) became popular.

17.3.4 Fairchild Unit 627 Variable Equalizer

さらに Reeves では、録音エンジニアや音楽ディレクタがマスタリング時に望みの音を作るための 汎用可変イコライザ(プログラムイコライザ)を活用していた、という非常に興味深い記述があります。主に78回転盤などのLP復刻など、ダビング盤制作時の話のようですが、オリジナル音源の録音にも触れられています。

Wortman’s 1949 article also mentions Variable Equalizer (Program Equalizer) so that recording engineers and music directors could make desired sound with it, especially when dubbing from 78 rpms to LP masters. It was also used for recording original music.

Each dubbing presents an individual problem to the recording engineer whose conscientious ambition is to make the new release as perfect as the state of the art will permit.

各ダビング作業においては、担当するエンジニアに個々の問題を提示する。録音エンジニアは良心に基づいた野心を持ち、最新技術が許す限り、新しいリリースを可能な限り完璧にしようとするものである。

Also, in recording original music, the recording engineer, musical director, or other person supervising the audio quality may desire heavier bass or middle register, or more brilliance than is obtained by natural studio acoustics. These conditions all indicate the need for a versatile equalizer that can selectively boost or attenuate: various portions of the audio band simultaneously. Such a variable equalizer is not required to deliver power or voltage amplification. It essentially a zero gain device. All signal amplification is achieved by other elements in the recording system.

また、オリジナル楽曲の録音においても、録音エンジニアや音楽監督など、音質を監修する人が、スタジオの自然な音響で得られる音よりも重低音や中音域を重めにしたり、よりブリリアントな輝きの音を求めたりすることがある。これら全てのことから、オーディオ帯域のさまざまな部分を選択的かつ同時に増幅したり減衰したりできる、汎用性の高いイコライザが必要とされている。このような可変イコライザには、アンプのような増幅の必要がなく、本質的にゼロ・ゲインのデバイスである。信号増幅は、録音システム中の他の機器(アンプなど)によって達成される。

The variable equalizer must deliver, through continuously variable controls, a broad peak at any of the bass frequencies from QO to 100 cycles and at any of the treble frequencies from 4,000 to 10,000 cycles. Not only must it be possible to select the frequencies at which equalization is to take place, but the degree of equalization must be adjustable in amplitude from zero (flat response) to a maximum boost of 16 db. Separate controls are needed for roll-off of low and high frequencies, and there must be no interaction between the high and low frequency controls. Such a basic unit finds wide application in professional recording.

可変イコライザは、Q0〜100Hzの低音周波数帯域、および、4,000Hz〜10,000Hz の高音周波数帯域のいずれにおいても、連続する可変コントロールによって広いピークを提供しなければならない。イコライジングを施す周波数を選択できるだけではなく、0(フラットレスポンス)〜最大16dBまでイコライジングによる増幅量を調整できなければならない。低域と高域のロールオフには別々のコントロールが必要で、この両者に相互作用があってはならない。このような基本的なユニットは、プロの録音現場で広く使われているものである。

“Design of Recording Systems, Part 1”, Leon A. Wortman当時 Fairchild 社がラインアップしていた可変イコライザは Fairchild 627 という型番で、アクティブタイプ、現存数は5台とのことです。数年後に業界で一世を風靡しあっという間に取り入れられることとなる、Pultec EQP-1/1A に代表される汎用可変イコライザが登場するまでにも、このようにして独自に音作りをしていたスタジオもあった、ということなんですね。

Fairchild had its own variable equalizer Fairchild 627 — an active equalizer, and only five units known to exist. Anyway, until Pultec EQP-1/1A came along and instantly became the industry standard within a few years, many recording studios utilized several Variable Equalizers to get the desirable sound.

以下の動画は、Fairchild 627 のインスパイアモデル、AML ez627 のものです。

The below movie captures the AML ez627 in action, inspired by Fairchild 627.

そして、続くパラグラフが非常に興味深いです。

The next paragraph is simply interesting enough.

Vertical and lateral NAB standards, private standards, broadcast audio line equalization, elimination of distorted and noise spectra, pre-emphasis and deemphasis are all controllable for recording and playing back with the one variable equalizer unit. By mechanically linking the cutterhead with a potentiometer that is electrically connected to the variable equalizer, this unit can be used as an automatic diameter-equalizer. This technique provides the unusual control of both equalization frequencies and maximum boost level.

縦振動盤用NAB規格、横振動盤NAB規格、プライベートな規格、放送音声ラインのイコライゼーション、歪やノイズの除去、録音時のプリエンファシスと再生時のデエンファシスはすべて、単一の可変イコライザユニットで制御が可能である。この可変イコライザに、電気的に接続されたポテンショメータとカッターヘッドを機械的にリンクすることにより、このユニットを自動補正イコライザ(Automatic Diameter Equalizer)として使用が可能となる。この技術により、イコライザ周波数と最大ブーストレベルの両方をコントロールすることが可能となる。

“Design of Recording Systems, Part 1”, Leon A. WortmanReeves / Fairchild では、そんな汎用可変イコライザ (Fairchild 627) を使って、カッティング径と連動した自動補正イコライザ (Fairchild 628) に仕立て上げていた、と。

It’s interesting to know that Reeves / Fairchild utilized the Variable Equalizers (Fairchild 627) to build Diameter Equalizers (Fairchild 628).

それはいいのですが、なんと、ディスク録音・再生EQとして、可変イコライザも使用可能、という、不思議な話が出てきましたね。これについては、のちほど セクション 17.4.2 で詳しく掘り下げます。

However, it’s somewhat strange to read the line saying that the variable equalizer unit can be used for disc recording/reproducing EQ as well. I will discuss on this topic later in the Section 17.4.2 of this Pt. 17 article.

17.3.5 Fine Sound Studios as of 1952

C. Robert Fine 氏 は1951年暮れ頃に Reeves Sound Studios から独立し、1952年3月、ニューヨーク郊外の集落 Tomkins Cove に自らの Fine Sound Studios を立ち上げます。

In late 1951, C. Robert Fine left the Reeves Sound Studios, and established his own Fine Sound Studios in March 1952. The location was at Tomkins Cove, suburb of New York.

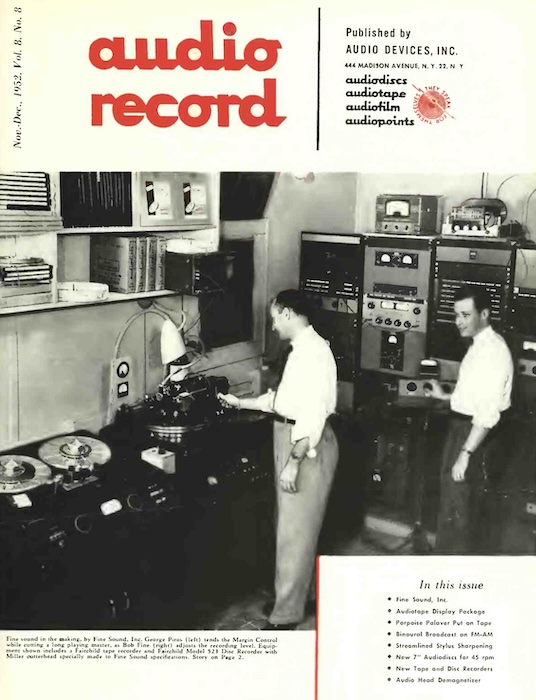

この頃の様子が、Audio Record 1952年11/12月号 の特集記事 “The Inside Story of FINE SOUND, Inc.” に捉えられています。著者は再び Leon A. Wortman 氏です。

The story of this is featured on Nov.-Dec. 1952 issue of the Audio Record magazine, as a featured article “The Inside Story of FINE SOUND, Inc.”. The author is, again, Leon A. Wortman.

Skipping a few periods of chronology and the details of the years spent as a lad shaving wax masters, inspecting styli, learning how to service and adjust equipment and make masters for a living, “Bob” Fine’s career has carried him through positions as Chief Engineer of Majestic Records, and Chief Engineer of the Disc and Tape Recording Divisions of Reeves Sound Studios. In March of this year he fulfilled a normal American ambition for independence by establishing Fine Sound, Inc.

ワックス原盤を削り、スタイラスを検査し、機器の修理と調整の仕方を学んだりした、少年時代の詳細は少し飛ばすとして、原盤制作で生計を立てるに至った “Bob” Fine 氏のキャリアは、Majestic レーベルのチーフエンジニア、そして Reeves Sound Studios のディスク・テープ録音部門のチーフエンジニアというポジションを経てきた。今年 (1952年) 3月、彼はついに Fine Sound Inc. を設立し、アメリカ人として当然の野心である「独立」を実現した。

The Inside Story of FINE SOUND, Inc. by Leon A. Wortman, Audio Record, Vol. 8, No. 8, Nov.-Dec., 1952, p.2

cover page (p.1) of Audio Record, Vol. 8, No. 8, Nov.-Dec., 1952.

Audio Record 誌1952年11/12月号の表紙に掲載された、当時の Fine Sound Studios のカッティングルーム

当該号表紙の写真には、次のようなキャプションがついています。基本的には、Reeves Sound Studios で使っていたのと全く同じ機材が写っているようです。

The front cover of this issue captures the Fine Sound Studios and its equipment, looking very similar (or identical) to what Mr. Fine and Mr. Piros used at the Reeves.

Fine sound in the making, by Fine Sound, Inc. George Piros (left) tends the Margin Control while cutting, a long playing master, as Bob Fine (right) adjusts the recording level. Equipment shown includes a Fairchild tape recorder and Fairchild Model 523 Disc Recorder with Miller cutterhead specially made to Fine Sound specifications.

Fine Sound 社での優れた (fine) 音の制作の模様。George Piros (写真左) が、マージンコントロール(可変ピッチ)を行いながらカッティングを行いつつ、Bob Fine(写真右)が録音レベルを調整している。Fairchild テープレコーダ、Fairchild 523 ディスクレコーダ(カッティングレース)、Fine Sound 専用仕様の Miller カッターヘッドなどの機材が写っている。

Audio Record, Vol. 8, No. 8, Nov.-Dec., 1952, p.1この表紙に使われた元となる高解像度写真のスキャンを Tom Fine さんが提供してくださったのですが、それを見た上で、Nicholas Bergh さんがその他の機器も特定してくれました。

Tom Fine-san kindly shared me (and Nick-san) a high-resolution scan of this cover photo. Then Nicholas Bergh-san kindly identified the equipment captured in the photo.

The main signal chain before the lathe is an Altec 322C limiter into an Altec 287 amp to drive the cutting head (amp uses big PP 845 tubes). The main EQ shown is the standard Cinema Engineering passive “program equalizer.” The 322C probably has enough make-up gain for the loss of this, but there is also an Altec preamp in the rack for make-up gain.

メインのシグナルチェーンはまず Altec 322C リミッターで、それが Altec 287 パワーアンプ(大型の PP 845 真空管が使われている)につながり、このアンプがカッティングレースのカッターヘッドを駆動する。(それらの前段に)メインのイコライザが写ってるけど、これは Cinema Engineering 社製のパッシブ式可変プログラムイコライザだね。恐らく 322C には(プログラムイコライザによる)ゲイン損失を補填するだけのメイクアップゲインを備えていると思うが、同じくメイクアップ用のラックには Altec のプリアンプも写っているね。

They would not use the program EQ for disc pre-emphasis. It was just used for minor corrective EQ like if something was “muddy” sounding and needed a little help.

(Cinema Engineering の)可変プログラムイコライザはディスク録音時のプリエンファシスとして使われていなかったはずだ。音が濁ったり籠ったりした場合にちょっと手直しが必要な場合など、そういったちょっとした補正用に使われたんだね。

There would have been a passive filter just for the recording curve like those shown in the catalog. Often there was also a high-pass and low-pass filter option in the cutting chains.

(この写真には写ってないけど)、録音用プリエンファシス専用の(Cinema Engineering 社の当時のカタログに掲載されているようなタイプの)イコライザが設置されていたはずだ。当時のカッティングチェーンにはさらに、オプションとしてハイパスフィルタやローパスフィルタが組み込まれていることも多かったんだ。

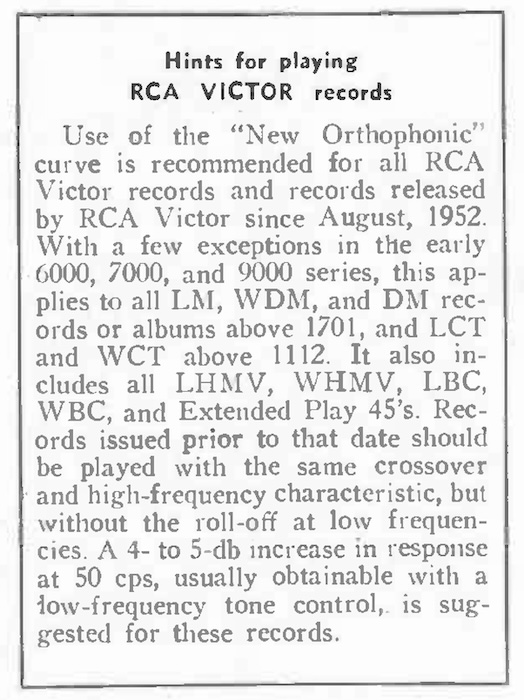

quoted from the email written by Nicholas Bergh to me (and to Tom Fine) on Jun. 28, 2023.この Fine Sound Studios でカッティングされた Mercury 向けの全LPは、RIAA 移行前は AES 標準再生カーブにあわせた録音特性でカッティングされていましたので、自作の AES 録音用イコライザ、または Cinema Engineering 社や Fairchild 社などに特注してもらった AES 録音用イコライザが、パワーアンプの前段に設置されていたのでしょうね。

Before the transition to the RIAA Recording/Reproducing Characteristics, all records cut at the Fine Sound Studios were cut with the curve for the AES Standard Playback Curve. So Mr. Fine and Mr. Piros could have used their self-made AES recording equalizer, or custom-made recording equalizer (by Cinema Engineering or Fairchild), inserted before the power amplifier that drove the cutterhead.

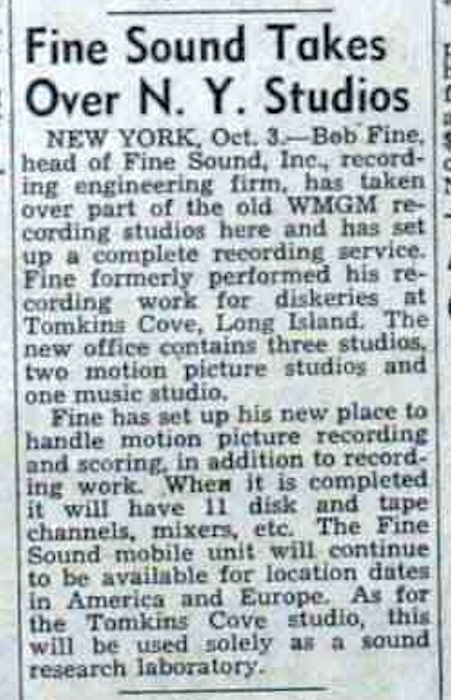

もともとはニューヨーク州ロックランド郡ストニーポイントの小さな集落 Tomkins Cove に居を構えた Fine Sound Studios でしたが、1953年10月にニューヨーク5番街711の WMGM Studios に移動し、ここが新しい Fine Sound Studios となります。WMGM Studios を所有していたのは Loews / MGM で、C. Robert Fine 氏が映画用に開発したマルチチャンネル光学サウンドトラックシステム PerspectaSound に Loews / MGM が興味を持ち、Fine Sound Inc. ごと権利を取得、WMGM Studios に移動させた、ということのようです。

Fine Sound Studios was originally located at Tomkins Cove, a hamlet in the Town of Stony Point, Rockland County, NY. Then in October 1953, Fine Sound moved to the new location at 711 Fifth Ave, NYC, previously WMGM Studios. In fact, Loews / MGM owned the WMGM Studios (1948-), and it acquired Fine Sound Inc. and Mr. Fine’s invention PerspectaSound (multi-channel optical soundtrack system for movies), then Fine Sound Studio was moved from Tomkins Cove to the WMGM Studio.

source: “Fine Sound Takes Over N.Y. Studios”, The Billboard, October 10, 1953, p.18.

1953年10月3日付のニュースとして、Fine Sound Inc. が WMGM Studios に入ると伝える記事

WMGM Studios といえば、幾多の重要ジャズ録音が行われたスタジオでもあり、Fine Sound Studios と名前が変わっても Verve 系 (Clef/Norgram) や Mercury / EmArcy 系の多くのジャズ録音で使われたスタジオでもあります。

Many important Jazz recordings were conducted at the WMGM Studios, and after the name changed to Fine Sound Studios, more of the Jazz recordings for Verve (Clef/Norgran) and Mercury / EmArcy labels were done there.

訴訟など大人の事情で1956年に Fine Sound Studios をたたまざるを得なくなった Fine 氏ですが、翌年1957年からマンハッタン57丁目のグレート・ノーザン・ホテル内で Fine Recording Inc. を開始、再び第一線で活躍することになります。

Due to a complicated situation including lawsuits, Mr. Fine had to give up Fine Sound Studios in 1956. But in 1957, Mr. Fine would start Fine Recording, Inc. in the Great Northern Hotel on 57th St., Manhattan, to make another history.

17.4 The Advent of Program (Variable) Equalizer

LPや45回転盤などマイクログルーヴ盤が登場し、磁気テープが全米の録音スタジオにどんどん導入されていった、1948年〜1950年頃。また、カッティング機材・技術もますます発展の途上にありました。

It was in 1948 to 1950 when LPs and 45 rpms (microgroove records) surfaced; and magnetic tape recorders instantly became popular in the studios.

特にカッター針周りの技術進化はめざましく、ホットスタイラス技術により、内周に近づいてもほとんど高域減衰せず、かつ静粛にカッティングできるようになったほか、従来は 10,000Hz あたりが上限であった記録がより高い周波数帯域まで充分にカッティングできるようになっていきました。

Also, the recording equipment and technique was still under the development. Especially the development of cutterheads was huge: “Hot Stylus” technique enabled smooth cutting, as well as adequate high frequency cutting even if the linear velocity decreased; it also broke the frequency limit, enabling to cut higher frequencies above 10,000Hz.

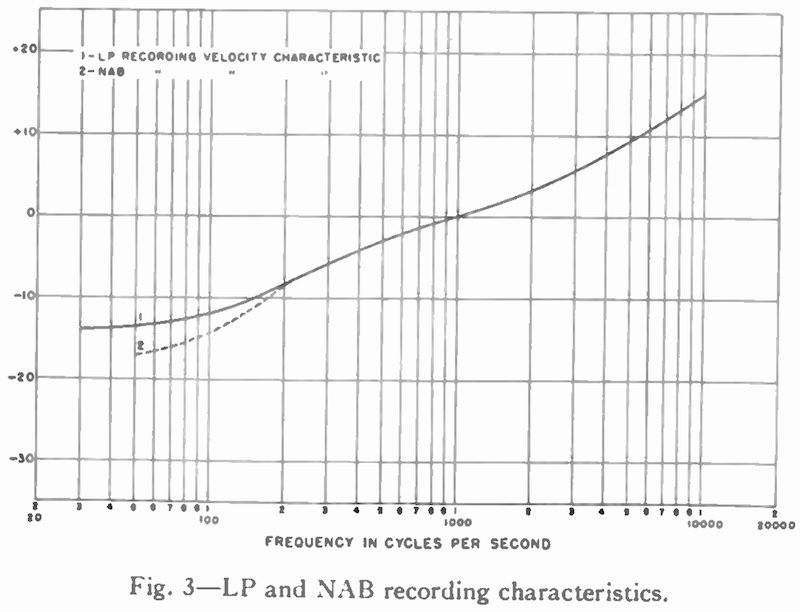

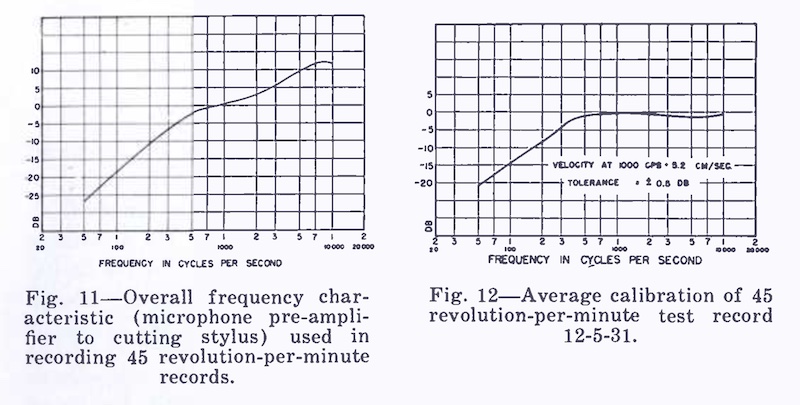

その変化にあわせて、1951年に発表された AES 再生カーブでは、15,000Hz まで規定されていました。1942年に初版が発表された16インチワイドグルーヴトランスクリプション盤用の NAB 録音再生カーブや、重低域を除き NAB カーブと同一とみなしてよい Columbia LP カーブなどは、上限 10,000Hz までしか規定されていなかったのに、です。

In order to meet these technological improvement, The AES Standard Playback Curve (1951) defines the frequency range up to 15,000Hz, while the NAB Recording and Reproducing Standards (initially published in 1942; revised in 1949) and the Columbia LP curve (same as NAB except the low-bass region) defined the frequency range only up to 10,000Hz.

このことにより、1940年代から盛んに議論されていた「NAB録音特性のプリエンファシスが強すぎるから弱めるべき」という話がますます現実味を帯びてきて、より高周波数の帯域でも歪まないように、プリエンファシスを弱める機運がますます高まっていきました。NAB カーブや Columbia LP カーブの高域プリエンファシスのままだと、10,000Hz より上の周波数帯域の高域増幅が強くなりすぎ、再生時のトレースが困難になったり、歪が発生しやすくなったりするからです。これが 1951年の AES 再生カーブの策定にも影響しているほか、のちの 1953年の NARTB カーブ、1954年の改訂 AES 再生カーブ、そして 1954年の RIAA カーブの策定へとつながります。

All these technological development led to further discussion of decreasing the high-frequency pre-emphasis, in order to avoid high frequency distortion. NAB and Columbia LP curves adopted 16 dB boost at 10,000Hz, which would theoretically lead excessive boost above 10,000Hz, resulting poor tracking (with tonearms and pickups at the time) and excessive distortion. This would be the main reason of the future standards: 1951 AES (12 dB boost at 10,000Hz), and 1953 NARTB / 1954 new AES / 1954 RIAA (13.7 db boost at 10,000Hz).

復習を兼ねて、1951年1月に発行された “AES Standard Playback Curve” 論文の該当部分(Pt. 16 セクション 16.4.2)を再度引用しておきましょう。

Below is the quotes again from the “AES Standard Playback Curve”, originally published in January 1951. It is previously quoted in the Pt. 16 Section 16.4.2 of my article.

The majority of engineers active in the recording field have felt for some time that the degree of high-frequency emphasis prescribed by the NAB transcription characteristic is excessive. The trend in modern microphones and amplifiers to a wider frequency range, approaching 15,000 cps, and the use of acoustically brighter studios have made this problem much more difficult. With this extended range, the acceleration of the reproducing stylus becomes a limiting factor.

録音現場で活躍するエンジニアの大半は、NABのトランスクリプション盤用に規定されている高周波帯域でのプリエンファシスが過剰である、と以前から感じてきたところである。近年のマイクロフォンやアンプでは、15,000Hz に迫る広い周波数帯域を扱えるようになってきており、また音響的に明るいスタジオが好んで使われるようになってきたため、このプリエンファシスの問題はさらに難しいものとなっている。周波数帯域が広くなればなるほど、再生用スタイラスの追従可能な加速度が制限要因となってしまう。

Consequently, it was deemed necessary to restrict the degree of high frequency rise used in recoring. This was accomplished by making the reproducing characteristic roll off only 12 db at 10,000 cps — approximately 3 db below the NAB specification — and continuing the response out to 15,000 cps. By doing this, the high-frequency situation has been alleviated somewhat.

そのため、録音時の高域プリエンファシスを抑え気味にすることが必要となる。再生特性において、10,000Hz でのロールオフを 12dB だけロールオフさせる(これは NAB 規格より約 3dB 少ない)、15,000Hz までレスポンスを継続させることによって実現した。これにより、高域での状況は多少緩和されたことになる。

Since microphone and studio characteristics must be considered by the recording engineer, it is required that the sum of the electrical rise in the recording equipment and the acoustic rise in the microphone must not exceed the values shown by the reciprocal of the reproducing characteristic, unless it is intended to make the high end over-brilliant.

録音エンジニアは、マイクやスタジオの特性を十分に考慮せねばならないため、意図的に高域を過剰に強調する意図がない限りは、録音機器の高域増幅とマイクの高域増幅の和が、再生特性を反転した値を超えないよう、細心の注意を払う必要がある。

“AES Standard Playback Curve”, Audio Engineering, Vol. 35, No. 1, January 1951, pp.22, 44-4517.4.1 Pultec EQP-1 and other variable equalizers

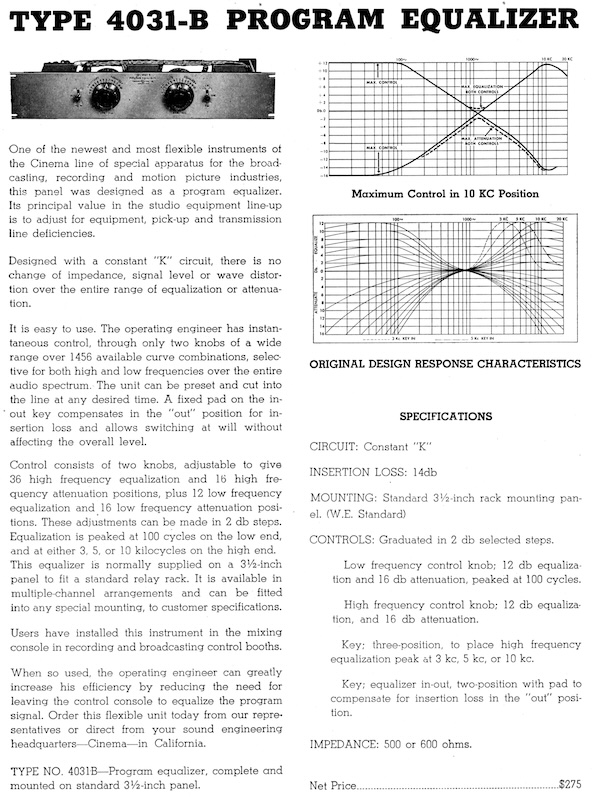

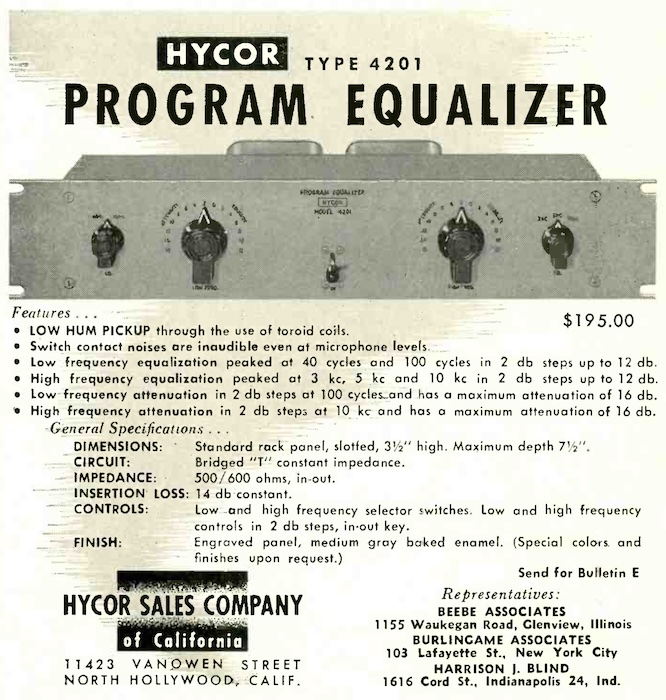

テープによる録音や編集の利便性向上、そしてカッティング技術の向上により、スタジオの現場ではより自由に音作りができる素地が整っていきました。上述した Fairchild 627 であったり、Cinema Engineering Type 4031-B であったり、Hycor Type 4201 であったり、Langevin EQ 258-A であったり、さまざまな可変イコライザが録音チェーンで使われようとしていました。

The convenience of magnetic tape recording and editing, as well as improvements in cutting technology, provided the basis for greater freedom of sound creation in the studios. Various “Variable Equalizers”, such as Fairchild 627, Cinema Engineering Type 4031-B, Hycor Type 4201, Langevin EQ 258-A, etc. were being used in the recording chain.

source: Cinema Engineering Company Catalog No. 11AX (possibly in 1951?)

1951年頃に発行されたと思われるカタログに掲載された、Cinema Engineering 4031-B 可変イコライザ

source: Hycor Type 4201 Program Equalizer Ad, Audio Engineering, Vol. 37, No. 11, November 1953, p.54.

そんな中、あっという間に全米の録音エンジニアの間でデファクトスタンダードとして導入されたのが、1951年に登場した、かの Pultec EQP-1 可変イコライザ、および後継の EQP-1A です。

Meanwhile, the Pultec EQP-1 was introduced in 1951; and its successor EQP-1A quickly became the de facto standard among recording engineers throughout the United States.

EQP-1: image obtained from: “A BRIEF HISTORY OF THE PULTEC COMPANY” by Mark Williams.

EQP-1A: image obtained from the PULTEC website.

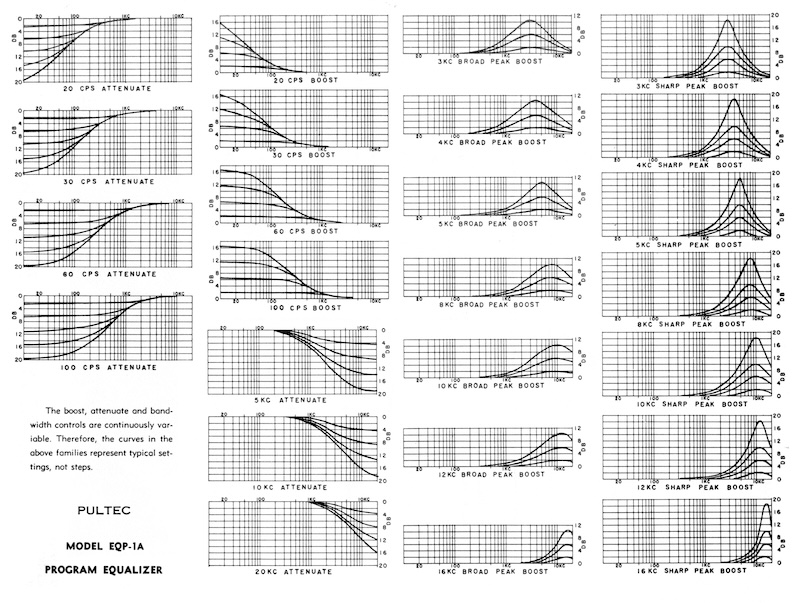

source: Pultec EQP-1A Equalizer Manual (1950s?)

Pultec EQP-1A マニュアルに掲載された、可変イコライザカーブの例

EQP-1 最初期ユーザのひとりである、Capitol (1946-1951) → MGM (1951-1957) の録音エンジニア Clair Krepps 氏 (1918-2017) へのインタビューによると、1950年代当時はマイクごとに特性がバラバラで、スタジオで鳴っているナチュラルな音をそのまま記録するために、可変イコライザが必要だった、そこで MGM 移籍直後の1951年、旧知の仲であった Pultec (Pulse Technology) 創設者 Eugene Shenk と Oliver Summerland に前金 $250 を払って制作を依頼した、と語っています。

There is an interview with Clair Krepps (1918-2017), a recording engineer at Capitol (1946-1951), then at MGM (1951-1957), and one of the first EQP-1 users. According to the interview, he insisted “what the industry needs is an equalizer”, because “An equalizer is the tool to correct the deficiencies of microphones, room acoustics, or for special effects”. So in 1951 (when he resigned from Capitol and moved to MGM) he asked his old acquaintances, Eugene Shenk and Oliver Summerland (founders of Pultec = Pulse Technology) to build such variable equalizers for $250 up front.

Susan Schmidt Horning 氏の著書「Chasing Sound: Technology, Culture, and the Art of Recording from Edison to the LP」にも、以下のような一節を確認できます。

Susan Schmidt Horning’s book “Chasing Sound: Technology, Culture, and the Art of Recording from Edison to the LP” also has the following paragrah:

The early equalizers, made by Cinema Engineering for the movie industry, posed problems when used in mastering phonograph records. They were noisy, made audible clicks when adjusted, and caused a full twenty-four decibel loss, which required the use of another amplifier to correct. Krepps, who hated using them, supported the development of the first quality equalizer for recording, made by Oliver Summerlin and Gene Shenk, two New Jersey audio engineers.

初期のイコライザは、Cinema Engineering 社によって映画産業用に作られたものだったが、レコードのマスタリングに使用する際には問題があった。ノイズが多く、調整時にクリック音が聞こえた。また 24dB の減衰が発生するため、別途アンプが必要となった。Krepps はこのようなイコライザの使用を嫌い、ニュージャージー州のオーディオエンジニア、Oliver Summerlin と Gene Shenk による初の高品質録音用イコライザの開発を支援した。

“Chasing Sound: Technology, Culture, and the Art of Recording from Edison to the LP”, p.114, by Susan Scmidt Horning, The John Hopkins University Press, 2013.ともあれ、EQP-1A に代表される可変イコライザが録音スタジオのデファクトスタンダードになったことにより、録音エンジニアは、特にポピュラー音楽向けに、思い思いの音を自在に作れるようになりました。つまり、ディスク録音再生カーブとは独立した「音作り」です。