EQカーブの歴史 や ディスク録音の歴史を、私が学ぶ過程を記録した本シリーズ。前回 Pt.24 では、録音チェーンおよび再生環境における周波数応答特性や位相特性が変化しうるパターンについて調べ、可変イコライザ等の使用による音作りが(特にポピュラー音楽系で)多く行われていることを改めて学びました。また、各種CDリイシュー音源の比較により、当時のシングルマスター、当時のLPマスター、マルチトラックマスターからのリマスター、などを比較することで、ディスク録音イコライザを通過する前の音の違いが確認できることも紹介しました。

This series have documented my process of learning the history of EQ curves and disc recording. In the previous Pt.24, I examined the patterns in which frequency response characteristics and phase characteristics can be changed in the recording chain and reproducing environment, and I learned again that the sound creation (especially in popular music) is often done through the use of variable equalizers and the like. I also introduced the comparison of various CD reissues to confirm the differences in sound between single masters of the time, LP masters of the time, remastered from multi-track masters, etc., before passing through the disc recording equalizer.

最終回 となる今回 Pt.25 は、2年以上に及び調べ学んできた膨大な内容を総括した 要約(復習)です。諸説多きディスク録音EQカーブについて、現時点で分かっていることを整理し、現時点での私の理解に基づき、最後に結論めいたものを記しています。また、少しでも読みやすくするため、仮想キャラ2名によるカジュアルな対話形式を挿入してみました(笑)

This Pt.25, which will be the final part, is a summary of the vast amount of information that I have learned and researched over the past two years. I will then summarize what is currently known — and some tentative summary and conclusion based on my current understanding of many thories — about the EQ curves of disc recordings. Also, in order to make it as easy to read as possible, I have inserted casual dialogues between two virtual characters 🙂

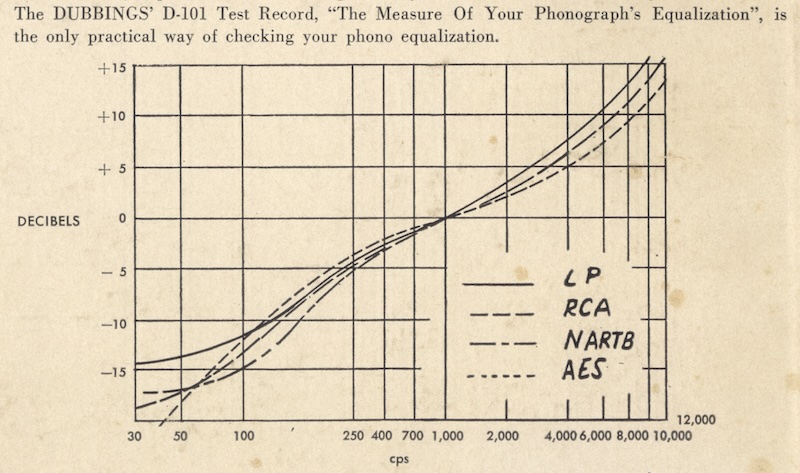

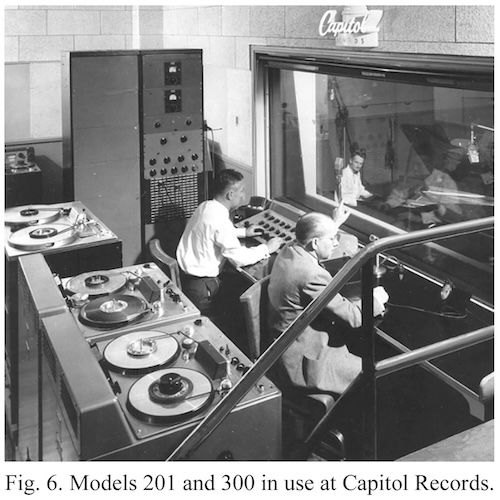

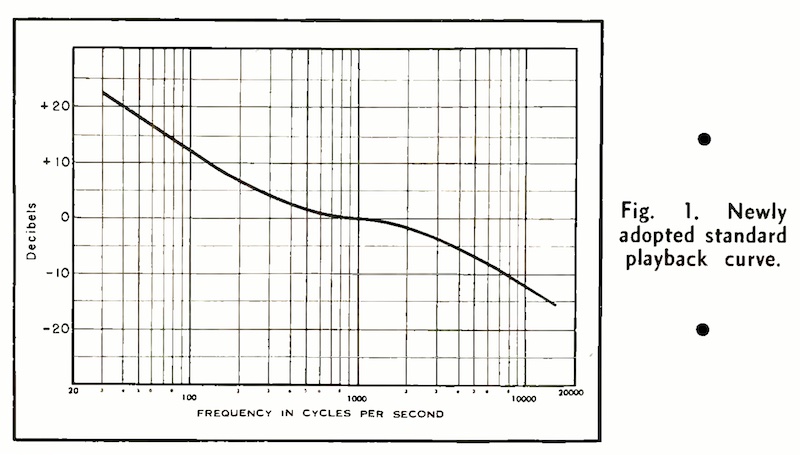

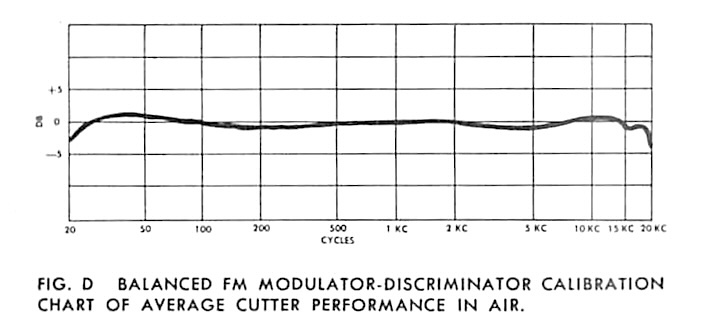

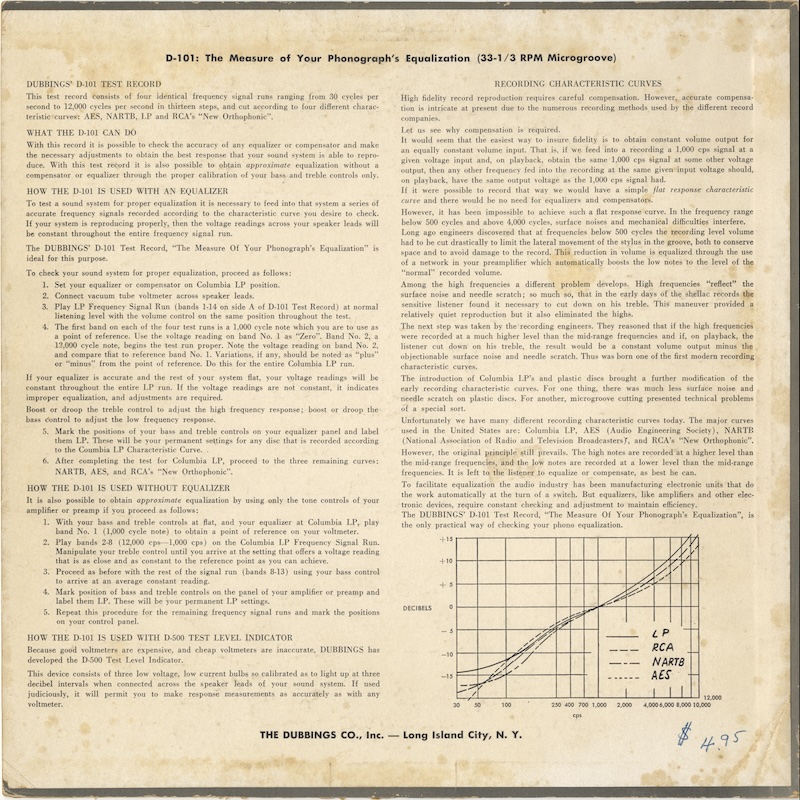

source: The Measure of Your Phonograph’s Equalization (Dubbings D-101, 1953)

from my own collection

毎回書いている通り、筆者自身の学習過程を記したものですので、間違いの指摘や異論は遠慮なくお寄せください。

As I noted in every part of my article, this is a series of the footsteps of my own learning process, so please let me know if you find any mistakes on my article(s) / if you have different opinions.

Contents / 目次

- 25.0 Before We Proceed / はじめに

- 25.1 How the “Disc Recording Equalizing” was born

- 25.2 Toward the Inception of “High-Frequency Pre-Emphasis”

- 25.3 Electrical Transcription Discs

- 25.4 Pre-emphasis with consumer 78rpms

- 25.5 Piezoelectric Pickups and its Reproducing Characteristics

- 25.6 NAB Standards (1942) and Sapphire Club in the WWII Era

- 25.7 The Birth of “Long-Playing” “Microgroove” Records and More

- 25.8 NARTB (1953) / AES (1954) / RIAA (1954) Characteristics

- 25.9 After The Standardization

- 25.10 Frequency Test Records

- 25.11 Phono EQs in Consumer Amplifiers

- 25.12 History and Variety of EQ Curve List

- 25.13 Conclusion and My Final Thoughts / 結論、および雑感

- 25.14 Notable References (for my entire articles)

- 25.15 Special Thanks To…(titles omitted, 敬称略)

25.0 Before We Proceed / はじめに

本 Pt.25 は、この2年強を通じて学んできたことのざっくりまとめとなります。大量の書籍、技術資料、論文、雑誌記事と出会ったことを改めて実感しました。また、非常に多くの有益な知見が得られた2年間でした。

This Pt.25 is a rough summary of what I have learned throughout the past 2+ years. I am reminded once again of the large amount of books, technical documents, academic papers and magazine articles that I have encountered. Also, it has been such a two-year period in which I have got a great deal of useful knowledge and insights.

例によって、非常に長いページとなっており、目を通されるのも一苦労かもしれません(すみません) が、Pt.0 〜 Pt.24 の大量の内容を可能な限りぎゅっと圧縮し、ほぼ時系列にディスク録音の歴史を追った内容となっています。

As usual, this here is a very lengthy page, and you may have a hard time reading through it (sorry for that), but the vast contents from Pt.0 to Pt.24 have been compressed as tightly as possible, and the history of disc recording has been followed almost in chronological order.

この灰色バックの囲みには、各セクションの概要を記しています。

This gray-back enclosure outlines each section.

本文中では、原則として「さまざまな資料や論文から分かった客観的事実」を述べています。

The main text states “objective facts known from various sources and papers” as a general rule.

仮想キャラ2名による吹き出しのカジュアルな会話部分には、

Casual dialogue parts between the two virtual characteris in the speech baloons like this…

わたし自身の理解と解釈に基づいた仮説・推測、および余談などが含まれています。

…contains hypotheses and reasonings based on my own understanding and interpretation, as well as digressions.

25.1 How the “Disc Recording Equalizing” was born

以下、特記なき場合は、すべて米国における歴史です。本稿では、英国や欧州における歴史についてはほとんど扱われていません。

All of the followings, unless otherwise noted, is a history in the U.S., while very little on the history in the U.K. or Europe is covered in the entire series of my articles.

まずは、ディスク録音の原理と録音EQカーブ誕生について。1920年代後半あたりの話です。

First, this section 25.1 deals with the summary of principles of disc recording, and the birth of recording EQ curves. The timespan is approximately the late 1920s.

25.1.1 Nature of Disc Recording: Constant Velocity

音をレコード溝の振幅に変換する際、周波数の高低によって刻まれる振幅に差が生じる。すなわち、音のレベルが同じであれば、低音(低周波数)は大きな振幅として記録され、高音(高周波数)は小さな振幅として記録される、すなわち定速度 (constant velocity) の特性を備える( Pt.1 セクション 1.1.1)。

When sound is converted into continuous groove amplitude engraved on the record surface, there is a difference in the amplitude engraved depending on the high and low frequencies. That is, if the sound levels are the same, low tones (low frequencies) are recorded as large amplitudes, and high tones (high frequencies) are recorded as small amplitudes, i.e. they have the property of constant velocity ( Pt. 1 Section 1.1.1).

ラウドスピーカーのウーファーは、目に見えるくらい前後に動くけど、スコーカーやツイーターはそこまで動いてないようにみえる、ってのと似てるような気がする。

It seems similar to how the woofer in a loudspeaker moves visibly back and forth, but the mid-range unit and the tweeter don’t seem to move that much.

確かに、同じ音圧レベル (SPL) であれば、低周波の方が大きく動くし、高周波では小さく動くことになるから、同様に考えられるね。

Certainly. For the same sound pressure level, the same would be true for low frequencies, which would move more, and for high frequencies, which would move less.

レコードのように螺旋状に横振動記録する場合、振幅が大きくなればなるほど、隣接する溝と接触しないように溝間隔を広くとる、すなわち1インチあたりの溝の数 (gpi, grooves per inch) の値を小さくする必要がある。しかし、そのことで、盤面に記録可能な時間が少なくなってしまう。また、振幅が大きすぎると、再生針が正確にトレースしにくくなってしまう問題もある( Pt.1 セクション 1.1.1)。かといって、全体的に記録レベルを下げて振幅を小さくすると、音量が下がり、結果としてサーフェズノイズに埋もれてしまうことになる。

In the case of spiral horizontal vibration groove like a disc record, the larger the amplitude, the wider the groove spacing must be to avoid contact with adjacent grooves, i.e. the smaller the value of the number of grooves per inch (gpi). However, this reduces the amount of time that can be recorded on the disc. Another problem is that too large an amplitude makes it difficult for playback needle to trace accurately ( Pt.1 Section 1.1.1). On the other hand, if overall recording level is lowered to reduce the amplitude, the volume will be reduced as well and consequently buried in the surface noise.

もし、低域を抑制せずに(ターンオーバーなしの定速度フラット)記録したとしたら、記録時間はどのくらい短くなるんだろう?

If it was to be recorded with unattenuated bass (constant velocity throughout all range without “turnover”), how much shorter would the recording time be?

一概には言えないけど、相当短くなるだろうね。一例として、英Wireless World誌1954年10月号に掲載された O.J. Russell 氏の解説記事 “Stylus in Wonderland” 中では、12インチ78回転盤は通常片面に5分くらい記録できるが、「もし低域抑制なしにしたら1分未満になるだろう」と書かれてるね。

It’s hard to say, but I guess it would be considerably shorter. As an example, in the article “Stylus in Wonderland” by O.J. Russell in the Oct. 1954 issue of Wireless World UK magazine, it says that a 12-inch 78rpm disc can usually hold about 5 minutes on each side, but “it would have a possible playing time of less than a minute with an unattenuated bass characteristic”.

そんなに違うんだ!低域の振幅ってそんなに幅をとるんだね。

It was that different! The amplitude of the low frquency range takes up so much width.

250Hz あたりが下限だったアコースティック録音時代と比べて、電気録音時代にはさらに低域がカッティングできるようになったから、この問題が生じたってことだね。ちなみに、電気録音最初期の特性グラフをみると、低域はおおよそ100Hz、がんばって80Hzくらいまではいけてたみたいだ。

Compared to the acoustic recording era, when the lower limit was around 250Hz, the electrical recording era allowed for even more low-freqency cutting, which was why this problem arose. Incidentally, looking at the characteristic graph of the early period of electrical recording, it seems that the lowest frequency was approximately 100Hz, or down to 80Hz at the best effort.

それに、当時は可変ピッチなんてなくて、基本的には固定ピッチでカッティングしてたんだよね( LPのオールアナログカッティングとディジタルディレイ 参照)。

Besides, there was no such thing as “variable pitch” cutting back then, and the recording was cut with a “fixed pitch” ( see also: All Analogue Cutting vs Digital Delay, written only in Japanese).

いわゆる「ダイレクトカッティング」だからね。また、ディスク録音機器もまだそんなに複雑な制御ができなかった時代だろうしね。

It was what we call “direct-to-disc” cutting. Also, disc recording equipment of the time would not have been capable of such complicated control.

25.1.2 The Dawn of Electrical Recoring and “Turnover Frequency”

アコースティック録音の時代は、実質的に記録可能な周波数帯域が非常に狭く(せいぜい 250Hz〜2,500Hz 程度)、また、そもそも録音用ホーンで収音した音をダイアフラムでそのまま振動に変換するしかなかった( Pt.1 セクション 1.1.1)。しかし、電気録音になると、最終的に下は 30Hz 程度まで捉えることが可能になったため、溝間隔の問題が顕在化することとなった。

In the acoustic recording era, the frequency range that could be practically recorded was very narrow (250Hz to 2,500Hz at most), and to begin with, the sound collected by a recording horn could only be converted directly into vibration by a diaphragm ( Pt.1 Section 1.1.1). However, when it came to electrical recording, it became possible to capture sounds down to about 30Hz at best, and the problem of groove spacing became appaent.

そこで、ある周波数より下の領域を定振幅 (constant amplitude) の特性( Pt.1 セクション 1.1.2)に抑え込む、すなわち1オクターブ下がるごとに -6dB となるように記録することで、溝間隔を広げずに記録することを可能とした。そして再生時には、その分低域を増幅することとした。

Therefore, the region below a certain frequency was suppressed to the constant amplitude characteristic ( Pt.1 Section 1.1.2), i.e. -6dB down per octave, which made it possible to record without widening the groove spacing. The low frequency range is then amplified during playback.

この定速度と定振幅の切り替わりとなる周波数のことを、ターンオーバー周波数 と呼ぶ。

The frequency at the boundary between constant velocity and constant amplitude is called the turnover frequency.

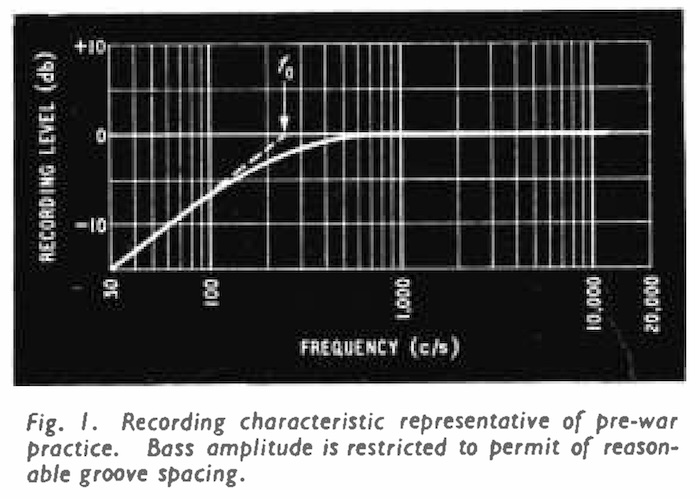

つまりこのグラフが電気録音最初期の録音カーブってことかな。ターンオーバー f0 のところがなだらかになってるのはどうしてだろう?

So, I guess this graph is the recording curve of the very early electrical recordings. Why is that the turnover f0 so smooth and round?

source: “Stylus in Wonderland”, O.J. Russell, Wireless World, Oct. 1954, p.505.

厳密に f0 で折れ曲がる理想的な特性を実現するには、実現する回路が複雑になってしまうからだね。後年のカーブ、例えば 1942 NAB カーブの元となった RCA Victor / NBC Orthacoustic カーブの解説記事でも「理想的なカーブを実現するためには非常に複雑な多段フィルタが必要となり、これを避けるために角を丸めるのが認められている」とあるよ( Pt.5 セクション 5.2.3)。

In order to accomplish the ideal characteristics such that the curve bends strictly at f0, the circuit to realize it would be complicated. Even in the 1942 article of RCA Victor / NBC Orthacoustic curve, which was the origin of the 1942 NAB curve, it reads that “In actual practice the corners at 100 cps and 500 cps are permitted to round off slightly thus avoiding the use of more complicated multiple section filters” ( Pt.5 Section 5.2.3).

実用化された世界初の電気録音は、Bell Telephone Laboratories (以下 Bell Labs) の J.P. Maxfield と H.C. Harrison によって開発され、1925年4月に初の電気録音盤が市販された( Pt.2 セクション 2.1.5)。また、1926年に Bell Systems Technical Journal に電気録音に関する技術論文「Methods of High Quality Recording and Reproducing of Music and Speech Based on Telephone Research」が発表された( Pt.1 セクション 1.1.1)。

The world’s first practical electrical recording was developed by J.P. Maxfield and H.C. Harrison of Bell Telephone Laboratories (Bell Labs), and the first electriccally recorded disc was commercially released in April 1925 ( Pt.2 Section 2.1.5). A technical paper on electrical recording, “Methods of High Quality Recording and Reproducing of Music and Speech Based on Telephone Research”, was published in the Bell Technical Journal in 1926 ( Pt.1 Section 1.1.1).

当時は、再生機器がアコースティックであり、ヴィクトローラ・クレデンザ のロガリズミックホーンを巧妙に設計し低域を絶妙に増幅することで、電気録音の録音特性にマッチした再生特性を実現していた( Pt.1 セクション 1.2.2)。

At that time, the reproducing equipment was still acoustic, and the Victrola 8-30 Credenza‘s logarithmic horns were cleverly designed to exquisitely amplify the low frequencies, thus matching the electrically recorded characteristics ( Pt.1 Section 1.2.2).

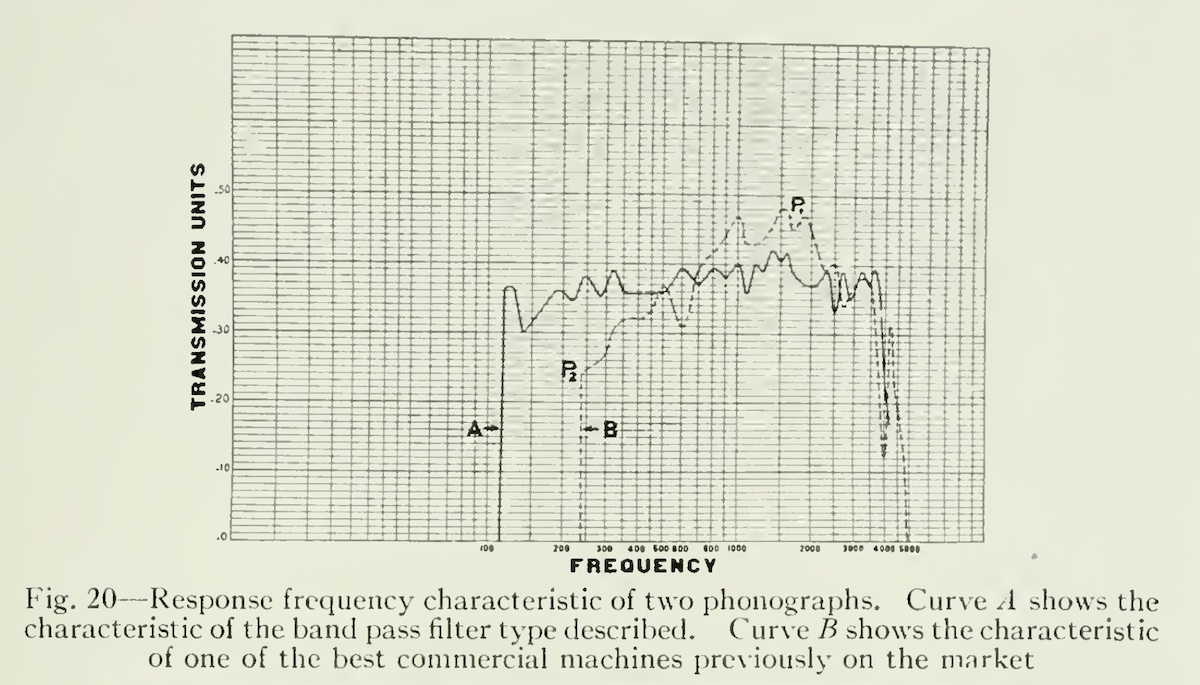

source: “Methods of High Quality Recording and Reproducing of Music and Speech Based on Telephone Research”, by J.P. Maxfield and H.C. Harrison, Bell System Technical Journal Vol.5, pp.493-523, 1926

この周波数特性グラフのAが、当時の電気録音ディスクを Victrola Credenza で再生した際の特性

電気録音でも、最初はアコースティック再生だったんだね。で、電蓄というか、電気再生はいつ頃始まったんだろう?

Even for electrical recordings, reproduction was initially acoustic! By the way, what was the first electric reproducer?

民生用としては、Victor より先に Brunswick が1925〜26年頃 Panatrope という電蓄を出したのが最初らしいよ( Pt.2 セクション 2.2.1)。その後少し遅れて Columbia から Kolster が、Victor Talking Machine から Electrola が登場したようだね( Pt.2 セクション 2.2.2)。

The first electroic reproducing system for consumer arguably was Brunswick’s Panatrope, introduced around 1925-26. It came out before Victor’s ( Pt.2 Section 2.2.1). Then, a little later, Kolster from Columbia and Electrola from Victor Talking Machine appeared on the market ( Pt.2 Section 2.2.2).

25.1.3 “Rubberline” Recorder and Its Recording Characteristics

この最初期電気録音当時のターンオーバー周波数は 250Hz であったとされている( Pt.1 セクション 1.2)。しかし実際には「200Hz〜300Hz」程度のゆるい精度で規定されていたことが、現存する当時の Bell Labs の技術資料から明らかとなっている( 2022 ARSC Conference における Nicholas Bergh 氏の発表スライド、ARSC 会員のみ閲覧可能)。

The turnover frequency at the time of this earliest electrical recording is said to have been 250Hz ( Pt.1 Section 1.2). However, Bell Labs’ technical documentation from that time, which is still in existence, reveals that the turnover frequency was actually specified with a loose accuracy of “200Hz to 300Hz” ( slides presented by Nicholas Bergh at the 2022 ARSC Conference, available only to ARSC members).

「200Hz〜300Hz」って、とてもゆるい定義だったんだね。

The definition of the turnover “between 200Hz and 300Hz” was very loose, I guess.

後年〜現代のような録音イコライザがなかった時代、カッターヘッドを巧妙に作り込むことでターンオーバーを実現していたからね。それだけ、のちの技術の発展がすさまじいってことでもある。

When there were no such things as recording equalizers like there were in later years and there are today, turnover was achieved by cleverly built physically in a cutter head. That’s how much technology has developed since then.

じゃあ大したことなかったってこと?

So you’re saying it wasn’t a big deal?

とんでもない。むしろ、今から100年前に、当時としては最先端だったラジオなどの電気工学の知見を援用して、機械的に等価になるように物理的に作った、ってのは、とてつもなく凄いことだよ。

It really was! Rather, it is tremendously amazing that 100 years ago, they were able to develop a mechanical equivalent by using the most advanced electrical engineering knowledge of the time, such as that of radios.

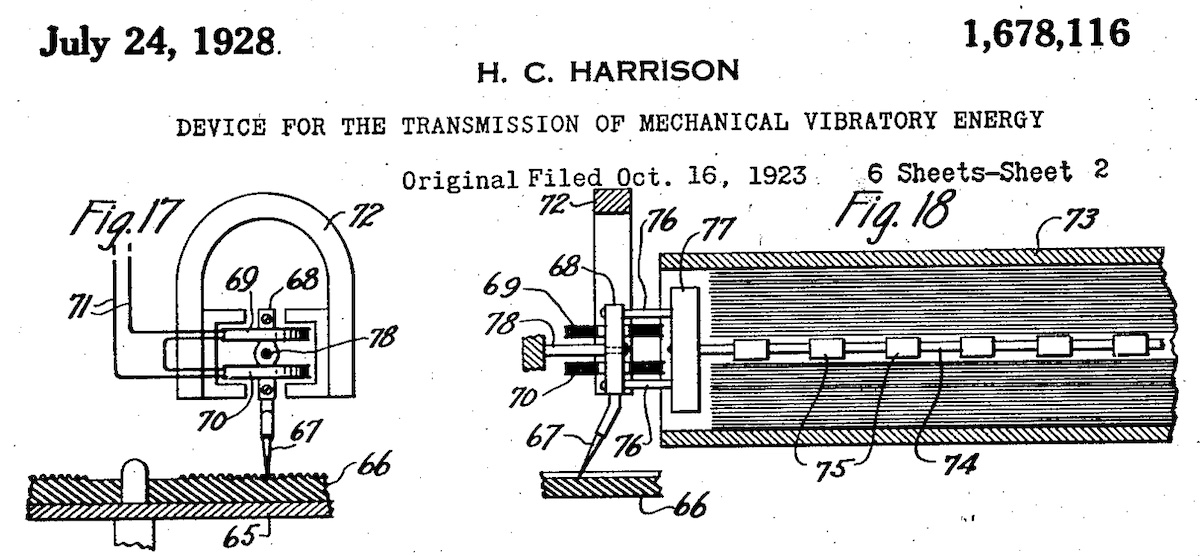

また、この電気録音黎明期においては、ディスク録音イコライザのような機器は使用されておらず、ターンオーバーの制御は、Bell Labs / Western Electric 製の通称「ラバーラインレコーダ」という当時のカッターヘッドの物理特性によって巧妙に実現されていた( Pt.1 セクション 1.2)。つまり、カッターヘッドの物理特性が、そのままディスク録音特性を規定していたことになる。

Also, in these early days of electrical recording, devices such as disc recording equalizers were not yet used, and turnover control was cleverly achieved by the physical characteristics of the cutterheads of the time, commonly known as “rubberline recorders” developed by Bell Labs / Western Electric ( Pt.1 Section 1.2). In other words, the physical characteristics of the cutterhead directly defined the disc recording characteristics.

source: “Device for the transmission of mechanical vibratory energy“, US Patent 1,678,116A, 1928

特許資料に登場する、ラバーラインとカッターヘッドの図版

Illustrations of “rubber-line” and electromagnetic cutter head, as shown in the Harrison’s patent document

そのため、経年劣化によりターンオーバーが変化してしまったり、気温や湿度によって特性が変化しやすかったと言われている( Pt.1 セクション 1.2.1)。よって、セッションによってターンオーバー周波数が一定でなかった可能性も考えられる。

Therefore, it is said that the turnover changed over time and that the properties were easily affected by temperature and humidity ( Pt.1 Section 1.2.1). Consequently, it is possible that the turnover frequency was not constant from a recording session to another.

抵抗やコンデンサの交換とか、スイッチの切り替えで微調整できたわけではなかった時代、録音特性の調整は大変だっただろうね。

It must had been difficult to fine-tune the recording characteristics in an era when it was not possible to replace resistors and capacitors, nor to adjust switches.

そうだね。それと、念の為強調しておくけど、確かに戦後以降は再生側にスイッチ切替式の可変フォノイコとかあるけど、ディスク録音イコライザは較正用ポジションを除き基本的には固定のものしかなかったからね。

Exactly. Also, just to emphasize for the record, there have been indeed switchable/adjustable variable phono equalizers on the playback side, especially since the post war period, but the disc recording equalizers were basically only fixed ones, except they had “FLAT” position for calibration.

で、この当時はどうやってターンオーバー値の調整をやっていたんだろう?

So, how were they fine-tuning turnover values at that time?

おそらく、テストカッティングをして現在の録音特性をチェックし、ずれていればラバーラインレコーダを Bell Labs / Western Electric に送り、微調整/リファービッシュ/新品交換を依頼、とかしていたんだろうね。けど、全てのレーベルが予算的に潤ってたわけではなかっただろうから、ずれていても気にせず使い続けられた、はたまた、ずれてることに気づかないまま使われていた、そんな例は少なからずありそうだね。

They probably did a test cutting to check the current recording characteristics, and if they found any discrepancies, they would send the rubberline recorder to Bell Labs / Western Electric for fine-tuning/refurbishing/replacing with new ones. However, not all labels at the time had a large budget, so there might have been a few cases where they continued using the recorders even if the cutters were out of alignment (or they didn’t even notice the difference).

高域はというと、当時の技術的限界から、当初は 4,500Hz あたり、ほどなく 5,500Hz あたりを上限にフラットに記録され、それより上は定加速度特性で急速減衰されていた( Pt.1 セクション 1.2)。これは、記録してもサーフェスノイズに埋もれてしまうから、という意味もあった。

High frequencies were initially recorded flat at around 4,500Hz and soon after at around 5,500Hz, due to the technical limitations of the time, and the above frequencies were rapidly attenuated by the constant acceleration characteristic (Pt.1 Section 1.2). This was conducted partly because the high-frequency portion of the recordings would be buried in surface noise.

source: “Recent Advances in Wax Recording”, Halsey A. Frederick, Bell System Technical Journal, Vol.8, Issue 1, pp 159-172 (January 1929)

archived at Internet Archive (archive.org)

電気録音黎明期って、高域はそんなに記録されてなかったってことなんだね。

So, in the early days of electrical recording, high frequencies were not recorded that much.

それでもアコースティック録音の頃と比べるとものすごい進化だったのは事実だよね。

Still, it is true that it was a tremendous evolution compared to the days of acoustic recordings.

25.2 Toward the Inception of “High-Frequency Pre-Emphasis”

続いて、録音EQのうち、高域プリエンファシス部分誕生前夜までの流れです。1920年代前半からラジオにシェアを奪われレコード売上枚数が激減( Pt.2 セクション 2.4)、追い討ちをかけるように1929年暮れに世界恐慌となった時期(Pt.3 セクション 3.2.1)、それでもレコードの技術開発と進化は地道に進んでいました。1920年代暮れ〜1930年代前半あたりの話です。

The next section is the eve of the birth of the high-frequency pre-emphasis portion of recording EQ. It had been a time when took market share away from records and sales declined sharply ( Pt.2 Section 2.4), followed by the Great Depression at the end of 1929 (Pt.3 Section 3.2.1). Nevertheless, technological development and evolution of phonograph records continued to progress steadily. The timespan is approximately from the late 1920s to the early 1930s.

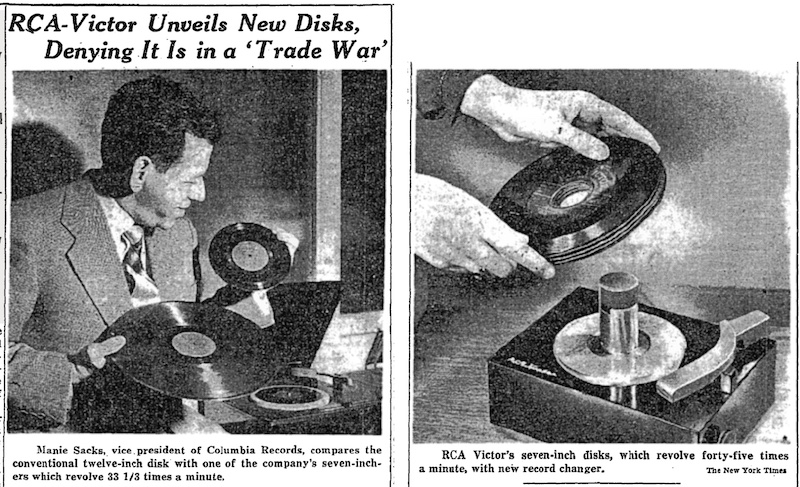

25.2.1 Vitaphone and “33⅓ rpm”

1926年、無声のみだった映画の世界にトーキーが登場、当初は映像を収めたフィルムと同期してディスクから音声を再生させるシステム Vitaphone によって実現されていた( Pt.4 セクション 4.1)。

In 1926, “talkies” were introduced, initially realized with the Vitaphone, a system that synchronized the playback of sound from a disc with the film containing the moving pictures ( Pt.4 Section 4.1).

サウンド・オン・フィルム(映像フィルム上の光学録音)ではなくて、サウンド・オン・ディスク(映像フィルムとレコードを同期させて再生)の時代だね。1931年頃にはサウンド・オン・フィルムに駆逐されたそうだけど。

Hmmm, it was the era of sound-on-disc, not sound-on-film (optical sound recording), which was apparantly eclipsed by sound-on-film around 1931.

ただ、当初サウンド・オン・ディスクの設備に投資したけど設備更新の余裕がなかった映画館が少なくなかったため、光学録音からダビングした Vitaphone の提供は1937年頃まで続いていたと言われているよ。

However, many movie theaters initially invested in sound-on-disc equipment but could not afford to upgrade their facilities, so Vitaphone dubbed from optical recordings continued to be offered until around 1937.

この Vitaphone は16インチ盤で、33⅓回転であり、現在の LP レコードの回転数はここに由来する。

The Vitaphone was a 16-inch disc with 33⅓ rpm, from which the current rpm of LP records is derived.

ところで前から疑問だったんだけど、33⅓ rpm っていう非整数な回転数に決められたのはなぜなんだろう?

By the way, I’ve wondered for a while, why 33⅓ rpm — which is a non-integer value — was chosen?

AC 60Hz 電源で 3,600 rpm て定速回転するモータがあったとして、これに 108:1 の比率のギアを使って減速すると、3,600 / 108 = 33.3333… = 33⅓ rpm となるよね。同様に、80:1 のギア比だと 3,600 / 80 = 45、これが 45rpm で、46:1 のギア比だと 3,600 / 46 = 78.2608695652、これが 78rpm と呼ばれているものの正確な回転数、ってことだね。で、当時の1,000フィートの35mmフィルムで11分間で、16インチの Vitaphone で11分間記録可能な線速度を実現する回転数ということで、33⅓ rpm が採用されたってことみたいだね。

Suppose we have a motor that rotates at a constant speed of 3,600 rpm on a 60Hz AC power supply. If we use a gear ratio of 108:1 to reduce the speed, we get 3,600 / 108 = 33.3333… = 33⅓ rpm. Simiarly, with an 80:1 gear ratio, we get 3,600 / 80 = 45 rpm, and with a 46:1 gear ratio, 3,600 / 46 = 78.2608695652 rpm, which is the exact speed of what is called 78 rpm. So, it seems that 33⅓ rpm was adopted to achieve a line speed that would allow recording on a 16-inch Vitaphone for 11 minutes on 1,000 feet of 35mm film at the time.

プロフェッショナル用途であったこの Vitaphone の技術は、のちにもう1つのプロフェッショナル分野であるラジオ放送局用のメディア、トランスクリプション盤の礎となり、その技術は折に触れ民生用レコードへと応用されていくこととなった。1931年に RCA Victor が民生用に販売した33⅓回転長時間レコード Program Transcription もその1つであった( Pt.4 セクション 4.2)。シェラック盤よりも高品質な合成樹脂を使用した Victrolac もこの際開発された( Pt.4 セクション 4.2.1)。

Technology of Vitaphone for professional use later became the foundation for another professional field of media, electrical transcription discs for radio stations, and it also was later applied to consumer records from time to time. RCA Victor’s “Program Transcription Records” for consumer use, 33⅓ rpm long playing records, was one of them ( Pt.4 Section 4.2). Victrolac, one of the earliest artificial plastic and better quality than shellac, was developed at the time ( Pt.4 Section 4.2.1).

25.2.2 Evolution of Rubberline Recorders and “500Hz” Turnover

民生用レコードのカッティングに使われていた Bell Labs / Western Electric 製ラバーラインレコーダは、徐々に改良が進み、1929年頃には 8,000Hz 程度まで記録可能となっていた( Pt.3 セクション 3.4.2)。ただし、カッティングされたワックス盤やメタルマスターには 8,000Hz 程度まで記録できていたとしても、当時の民生用シェラックレコードはシェラック樹脂が3割、残る7割が石灰岩や粘板岩を粉砕した粉(マイカパウダー)、カーボンブラック、コーパルガム、タールピッチなどで構成されていたため、サーフェスノイズが大きく、実際にはS/N比は30dBがせいぜいであった。

The Bell Labs / Western Electric’s rubberline recorders used for cutting consumer records were gradually improved, and by around 1929 they were capable of recording up to about 8,000Hz ( Pt.3 Section 3.4.2). However, even though wax discs (cut by rubberline recorders) and metal masters could record up to about 8,000Hz, consumer “shellac” 78rpm records at that time were made of shellac resin (30%), and the remaining 70% was made of crushed limestone or slate powder, carbon black, copal gum, tar pitch, etc., and such records’ S/N ratio was 30dB at best.

シェラック盤のシェラック含有率が3割だけで、岩を粉砕した粉が多く含まれていたなんて。それじゃシェラック盤じゃなくむしろ岩粉盤だね。

I can’t believe that the shellac content of the shallac record was only 30% and that it contained a lot of ground-up stone! Then it should not be called a “shellac record”, but rather a “rock-powder record” or something!

当時の蓄音機の針圧は数百グラムとかザラだったし、さらに鉄針だった。だから、純粋なシェラック樹脂だけでサーフェスノイズの少ない盤を作ったとしても、あっという間に溝が削られてしまう、だから岩粉を混ぜて針も摩耗させるようにしていた、って側面もあるよね。それで当時は岩粉のことを「抗摩耗剤」って呼んでいたんだと思う。

The needle pressure of phonographs at that time was usually several hundred grams, and moreover, the needles were made of iron. So even if a disc with low surface noise was made of pure shllac resin, the grooves would be worn away in no time, so rock ground-up stone was mixed in to wear away the needle. I think that’s why they called the ground-up stone “abrasive” back then.

一方、このラバーラインレコーダを使用するライセンス料金が非常に高く、1929年の

On the other hand, the license fees to use these rubberline recorders were extremely expensive, and the Great Depression of 1929 coincided ( Pt.3 Section 3.2.1). To avoid paying the expensive license fees, major companies began developing their own recording systems ( Pt.3 Section 3.2). However, the surviving actual recorders reveal that many of them were carbon-copy version ( Pt.3 Section 3.4.3) ( slides presented by Nicholas Bergh at the 2022 ARSC Conference, available only to ARSC members).

世界恐慌を受けて、米国でのレコード業界が壊滅的な打撃を受けたんだったよね。

The Great Depression devastated the record industry in the U.S., didn’t it?

なにしろ、1929年には全米で1億枚以上だったレコード販売枚数が、1932年には600万枚にまで落ち込んだんだからね。販売価格を大幅に下げざるをえなくなり、多くのレーベルが倒産したり大手レーベルに買収されたりしたのが1930年代前半だね。

In 1929, record sales in the U.S. were over 100 million copies, but by 1932, they had dropped to 6 million. The sales price had to be drastically reduced, and many labels wenb bankrupt or were bought out by major labels in the early 1930s.

それにしても、ライセンス料支払い回避のためにクローン開発なんて、法的にはかなりグレーな気がするけど…

Still, I think developing carbon-copy clones to avoid paying licensing fees is a very gray area legally…

当時はそういう時代だったんだろうね。そして、1940年代まで続く各社の秘密主義ってのも、ここら辺りが源流の可能性はありそうだね。

I guess that’s the way things were back then. And the secrecy of the companies that continued until 1940s may have its origin in these circumstances.

また、Columbia は 1930年〜1931年頃、RCA Victor は 1932年頃、それぞれターンオーバーを 500Hz に引き上げていたことが、当時のさまざまな資料から確認できる( Pt.3 セクション 3.4.2 および セクション 3.5)( 2022 ARSC Conference における Nicholas Bergh 氏の発表スライド、ARSC 会員のみ閲覧可能)。ちょうどこの1930年代前半頃に、米国における民生用レコードの録音特性は、ターンオーバー 500Hz がほぼ標準となっていた。一方、英国や欧州では、1950年代初頭までターンオーバー 250Hz(200Hz〜300Hz)がほぼ標準であった。

Various documents from the period confirm that Columbia and RCA Victor had increased their turnover frequency to 500Hz by about 1930-31 and 1932, respectively ( Pt.3 Section 3.4.2, Section 3.5) ( Pt.3 Section 3.4.3) ( slides presented by Nicholas Bergh at the 2022 ARSC Conference, available only to ARSC members). Just around this time in the early 1930s, the turnover frequency of 500Hz was almost the standard recording characteristic for consumer records in the U.S., while in the U.K. and Europe, the turnover of about 250Hz was the standard until the early 1950s.

米国だけターンオーバーが引き上げられたのには何か理由があったんだろうか。

Was there any reason why turnover was raised only in the U.S.?

まず、ターンオーバーを引き上げる、ということは、それだけ低域を十分に記録するための措置だよね。で、米国では早くから電気再生が普及したから、再生側でターンオーバー変更は、コンデンサ容量や抵抗値を変えるだけで対応可能ってことだね。

First of all, raising the turnover, that’s a measure to record enough low frequencies, right? And since electrial playback became popular in the U.S. early on, this means that turnover changes on the playback side can be handled by simply changing capacitance and resistance values.

じゃあ逆に、英国や欧州でターンオーバーが変更されなかったのは?

On the other hand, why was turnover not changed in the U.K. and Europe?

植民地が多かった英国・欧州では、アコースティック蓄音機が依然主流だったから、むやみにターンオーバーを引き上げられることがなかった、と言われているよ。同じ理由で、英国や欧州で遅くまで高域プリエンファシスが使われなかった(あるいは米国より控えめであった)という考察もあるね( Pt.9 セクション 9.2)。

It is said that in the U.K. and Europe, where there were many colonies, acoustic phonographs were still the norm, so turnovers were not raised unnecessarily. For the same reason, there is also the consideration that high-frequency pre-emphasis was not used (or was more modest than in the U.S.) until later in the U.K. and Europe ( Pt.9 Section 9.2)

25.2.3 Ribbon Microphones and “Voice Effort Equalization”

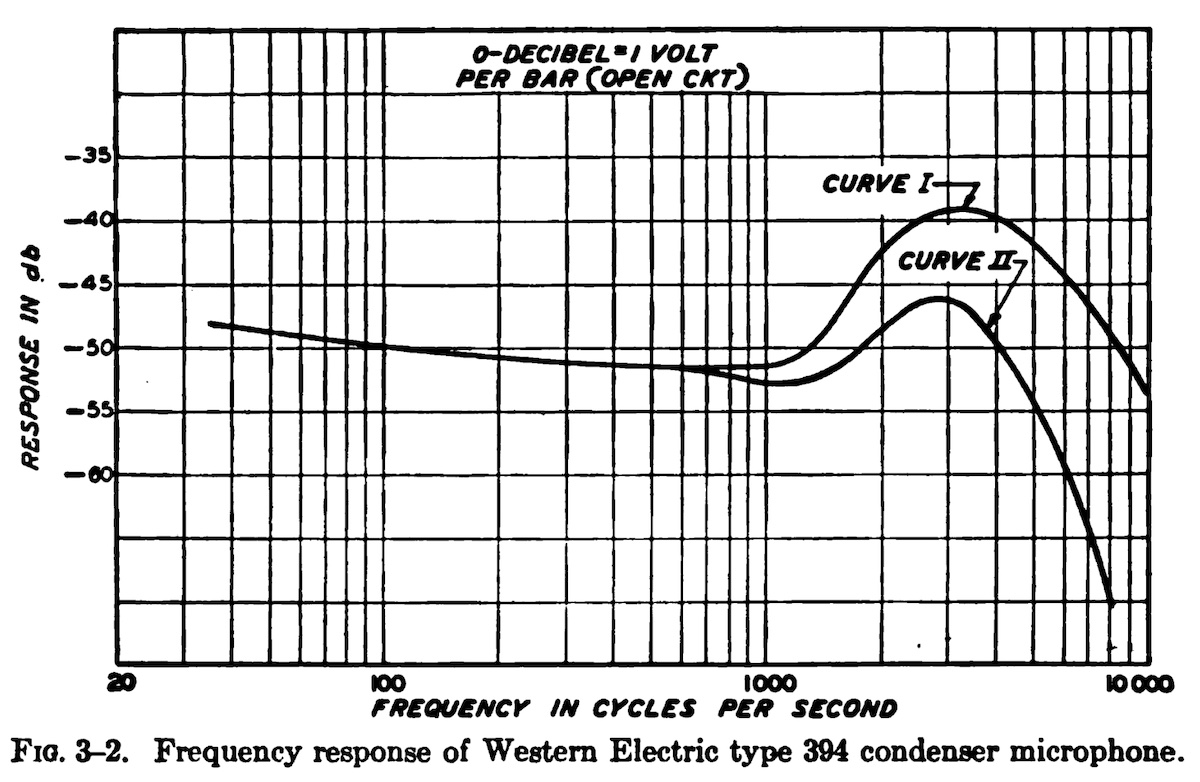

当時の民生用レコードでは、サーフェスノイズに負けないように高域を増幅して記録するための意図的な高域プリエンファシスはまだ用いられていなかったが、電気録音初期から使われていたコンデンサマイクは 3,500Hz あたりに +5〜6dB のピークを持つ特性であった(録音イコライザ目的ではなかったことに注意)( Pt.3 セクション 3.4.4)。これが、結果としてサーフェスノイズ対策の役目を果たしていたという説もある。

High-frequency pre-emphasis to amplify and record high frequencies to overcome surface noise was not yet used in consumer records at that time, but condenser microphones used since the early days of electrical recording had a characteristic of +5 to 6dB peak around 3,500Hz (note that this was not for recording equalization purposes) ( Pt.3 Section 3.4.4). Some believe that this served as a surface noise suppressor as a result.

録音・再生カーブ前提のプリエンファシスじゃなくて、当時のマイクの特性によって、たまたま高域がサーフェスノイズに埋もれないレベルで記録されていた、ってことだね。

So it was not the pre-emphasis as a recording/reproducing curve, but rather the characteristics of the microphones of the time, which happened to record high frequencies at a level where they were not buried by surface noise.

そうなるね。だから、電気録音黎明期については、そのような特性のマイクが使われてたか判明している盤については、そのマイクの特性も込みで高域を下げて再生してあげる方がいい、という立場の人もいるね。例えば、最初期の盤は 250N-6(ターンオーバー250Hz、ロールオフ 6dB at 10kHz)や 250N-8 が望ましい、とか。

That’s what it means. Therefore, there are those who argue that, in the early days of electrical recording, it is better to play back with the high frequencies lowered to include the characteristics of the microphones used, if it is known that microphones with such characteristics were used. For example, they suggest that 250N-6 or 250N-8 is preferable for reproducing early U.S. electrical 78 rpms.

source: “Elements of Sound Recordings”, p. 36, by John G. Frayne and Halley Wolfe, 1949.

Western Electric 394 コンデンサマイクの周波数特性グラフ。3.5kHz に +10dB 以上のピークがみられる

なるほどね、マイクのハイ上がりを打ち消したら、元の音に近づけられる、と。

I see. So if the microphone’s high rise was canceled, we would get closer to the original sound.

一方で、いやいや、そういうマイクの特性も込みで当時録音されたのだから、高域はそのままで再生する方がいい、つまり 250N-FLAT(ターンオーバー250Hz、ロールオフ 0dB at 10kHz)でいい、という立場の人もいるわけだね。どちらにも一理あることになる。ともあれこれが、78回転盤の再生カーブ一覧表が、諸説分かれている原因のひとつでもあるってことだ。

On the other hand, there are those who say “No, no, no, it’s better to reproduce the high frequencies as they are, since they were recorded at that time with such microphone characteristics included, so it’s adequate to be played with 250N-FLAT”. Both sides have a point. Anyway, this would be one of the reasons why there are so many different theories about the playback curves of 78 rpm recordings.

1931年にフラット特性のリボンマイクが登場した際、RCA ではコンデンサマイクの中高域ピークの音の方が好まれたため、リボンマイクのプリアンプにコンデンサマイクの中高域ピークをエミュレートするための回路 “voice effort equalization” が追加された( Pt.3 セクション 3.4.4 および セクション 3.4.5)。これがのちに、録音イコライザとしての高域プリエンファシスの源流となった可能性が指摘されている。

When ribbon microphones with flat characteristics were introduced in 1931, the mid-high peaks of condenser microphones were preferred at RCA studios, so an equalizer called “voice effort equalization” was added to the ribbon microphone preamplifier ( Pt.3 Section 3.4.4, Section 3.4.5). It has been pointed out that this may later had been the origin of the high-frequency pre-emphasis as a recording equalizer.

「高域プリエンファシスの源流」ってのは少し眉唾っぽい気もするけど、ともあれ、当初はコンデンサマイクの特性をエミュレートする回路をマイクプリアンプに取り入れ、これが後年ミキシングコンソールの後段に移動したってのは、R.C. Moyer 氏の有名な解説記事「Evolution of a Recording Curve」に書かれてるね。

The “origin of high-frequency pre-emphasis” seems to be a bit of an eyebrow-raising theory, but at any rate, R.C. Moyer’s famous article “Evolution of a Recording Curve” explains that the circuitry to emulate the characteristics of condenser microphones was initially incorporated into microphone preamplifiers, which were later moved to the rear stage of mixing consoles.

リボンマイク導入により、今まで慣れ親しんできた音が急に変わって、ミュージシャンからもスタジオエンジニアからも「前の音の方がよかった」と言われた、だからマイクのプリアンプに “voice effort equalization” が追加された、ってのは興味深いエピソードだね。

It is interesting enough that the introduction of ribbon mics suddenly changed the sound they had become accustomed to, and both musicians and studio engineers said that they preferred the sound of the condensor mics, so a “voice effort equalization” was added to the micrphone preamp.

で、その “voice effort equalization” の分を再生時にデエンファシスするか、しないか、も、また意見が分かれる、と。

And then there is also a difference of opinion as to whether the “voice effort equalization” should be de-emphasized during playback or not, right?

そうだね。更に言えば、例えば RCA Victor では、1938年頃までは 4,500〜5,500Hz 以上から、それ以降1947年頃までは 8,500Hz 以上から、それぞれロールオフした上でカッティングしていたそうだ。他レーベルもいろいろやっていただろうけど、詳細は記録に残っておらず確認できそうにない。そういった事情もあり、厳密にこだわろうとすると、単純な「ターンオーバー」「ロールオフ」の値の話だけでは解決しそうにないね。可変フォノイコを使っても「推奨近似値」でしかない、と。

Exactly. Furthermore, RCA Victor, for example, used to roll of and cut from above 4,500〜5,500Hz until about 1938, and from about 8,500Hz until about 1947, respectively. Other labels may have done so as well, but the details are not documented and survived and cannot be confirmed. Because of these circumstances, if we try to be strict about the theory, it is unlikely to be solved by just talking about simple “turnover” and “roll-off” values. Even if you use a variable phono preamp, it is only a “recommended approximation”.

25.3 Electrical Transcription Discs

続いては、民生用レコードとは独立して技術開発が進み、のちの標準規格化の礎になった、放送局用トランスクリプション盤について。録音特性に高域プリエンファシスとベースシェルフが登場しました。縦振動盤と横振動盤があり、当初は縦振動盤が高品質とされ有利だったが、Pierce & Hunt の研究により横振動盤の優位性が証明され、横振動盤が主流を勝ち取るまでの流れです。1930年代全般です。

This section summarizes the broadcast transcription disc, which was developed independently of the consumer records, and became the foundation for later standardization. High-frequency pre-emphasis and bass shelf appeard in recording characteristics. There were vertical and lateral discs, and initially vertical discs were considered to be of higher quality andhad an advantage, until Pierce & Hunt’s research proved the superiority of the lateral discs, then the lateral discs won the mainstream. The timespan is approximately in the entire 1930s.

25.3.1 “Hill-and-Dale” Vertical Electrical Transcription Discs

生放送が主流だったラジオ放送局で、録音済の音源を放送するメディアとして1929年に誕生した トランスクリプション盤 は、当初は78回転だったが、長時間放送対応のためほどなく16インチ33⅓回転盤が主流となった( Pt.4 セクション 4.3)。

Electrical Transcriptions, a.k.a. Radio Transcription Discs, debuted in 1929 as a medium for broadcasting pre-recorded sound sources on radio stations where live broadcasts were the norm, were initially 78 rpm. But soon became the norm for 16-inch 33⅓rpm discs to accomodate longer broadcast time ( Pt.4 Section 4.3).

16インチって大きいね。片面何分くらい収録できたんだろう。

16 inches is big! I wonder how many minutes could be recorded on one side?

当時の民生用78回転盤 (3mil) よりほんの少し細い溝 (2.5mil) で、まだマイクログルーヴじゃないから、LPよりは収録時間が短くて、片面最大15分程度だね。内周スタートのものと外周スタートのものがあり、レーベル面に記載があることが多かった。

The groove was slightly thinner (2.5mil) than the consumer 78 rpm discs of the time (3mil), and since they were not microgroove yet, the recording time was shorter than that of LPs, about 15 minutes maximum per side. There were two types of transcriptions, one with an inside start and the other with an outside start, which were often indicated on the label.

その頃、Bell Labs / Western Electric により1931年に初お披露目された高音質縦振動盤が登場( Pt.4 セクション 4.4)、World Program Service や Muzak などトランスクリプションレーベルで広く採用された。

Around that time, Bell Labs / Western Electric introduced high-quality vertical recording discs initially unveiled in 1931 ( Pt.4 Section 4.4), which was widely used by transcription labels such as World Program Service and Muzak.

Bell Labs / Western Electric が縦振動記録方式を採用した理由は、横振動記録に比べて記録密度をあげられること、当時の重いピックアップやトーンアームを使う横振動盤に比べて再生歪の点でも有利と結論づけられたこと、であった( Pt.4 セクション 4.4)。

Bell Labs / Western ELectric adopted the vertical recording method because it could increase recording density compared to lateral recording method, and it was concluded that it was advantageous in terms of playback distorton compared to lateral discs that used heavy pickups and tonearms of the time ( Pt.4 Section 4.4)

エジソンの蝋管やダイヤモンドディスクで採用されていた縦振動記録がまた復活したんだね。しかも当時は「横振動盤より高音質」が謳われていたんだよね。

Vertical (hill-and-dale) recording, which was used in Edison’s wax cylinders and diamond discs, was back again. And at the time, it was claimed to have “higher sound quality” than lateral discs, wasn’t it?

縦振動記録でピンチ効果歪の払拭、12インチ盤で最大片面20分の記録が可能、抗摩耗剤なしの盤質(当初はセルロースアセテート製)と針圧が5〜25グラムでサーフェスノイズが大幅減少、10,000Hz まで記録可能、と、当時としては夢のような高音質レコードだったんだね。

It was claimed that vertical recording eliminated pinch effect distortion; 12-inch discs could record up to 20 minutes per side; the disc quality (initially made of cellulose acetate) without abraisive and needle pressure of 5 to 25 grams greatly reduced surface noise; and recording was possible up to 10,000Hz… So this was a dream record of high sound quality at the time.

民生用78回転盤では結局採用されなかったけど、当時その可能性を高く評価する人が多かったんだね。

It was not adopted for consumer 78 rpms after all, but many people at that time highly valued the potential of “hill-and-dale” records.

一例として、Fortune 誌1939年9月号の記事「Phonograph Records」では、民生用レコードの新フォーマットとして縦振動盤を出したらいい、と力説されていたね( Pt.5 セクション 5.1.5)

As an example, in the article “Phonograph Records”, in the Sep. 1939 issue of Fortune magazine, it was strongly argued that the vertical discs should be introduced as a new format for consumer records ( Pt.5 Section 5.1.5).

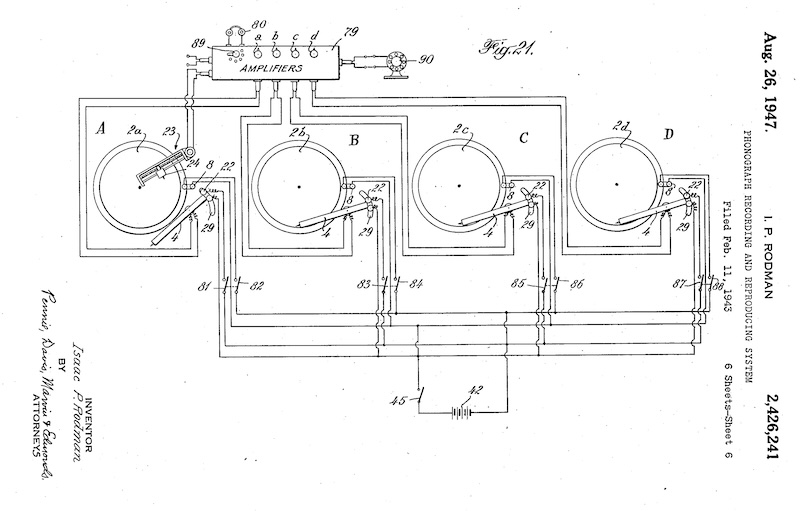

また、この WE 縦振動トランスクリプション盤で、世界で初めて 高域プリエンファシス を含んだ録音再生特性が採用された( Pt.4 セクション 4.4.1)。

In addition, this WE vertical transcription disc was the first in the world to adopt recording and reproducing characteristics that included high-frequency pre-emphasis ( Pt.4 Section 4.4.1).

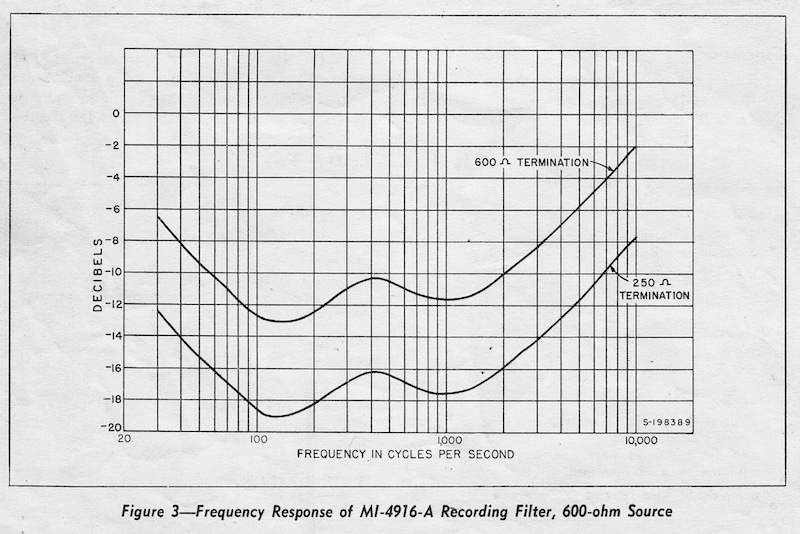

この縦振動盤用録音再生カーブは1種類で、パッシブLCR回路で構成された専用イコライザが使われた。録音特性を測定しプロットされた当時のグラフからも明らかなように、そのカーブは横振動盤用カーブとは大きく特性が異なり、現在の可変フォノイコライザ(ターンオーバー、ロールオフ、ベースシェルフ切替式)では正確な再生が不可能と考えられる( Pt.4 セクション 4.4.1)。

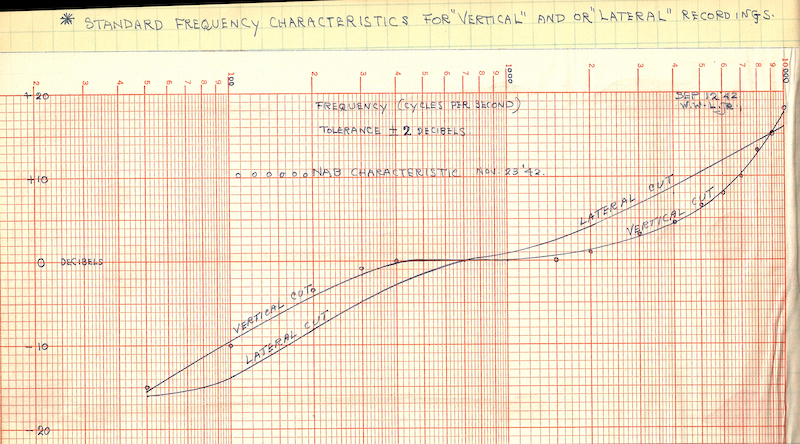

There was only one type of recording and reproducing curve for this vertical disc, and it used a dedicated equalizer composed of a passive LCR circuit. As is clear from the graphs of the time in which the recording characteristics were measured and plotted, the characteristics of that curve differed significantly from those of the curve for lateral transcription discs, and accurate reproduction would be impossible with today’s variable phono EQs (turnover, roll-off, bass-shelf switchable) ( Pt.4 Section 4.4.1).

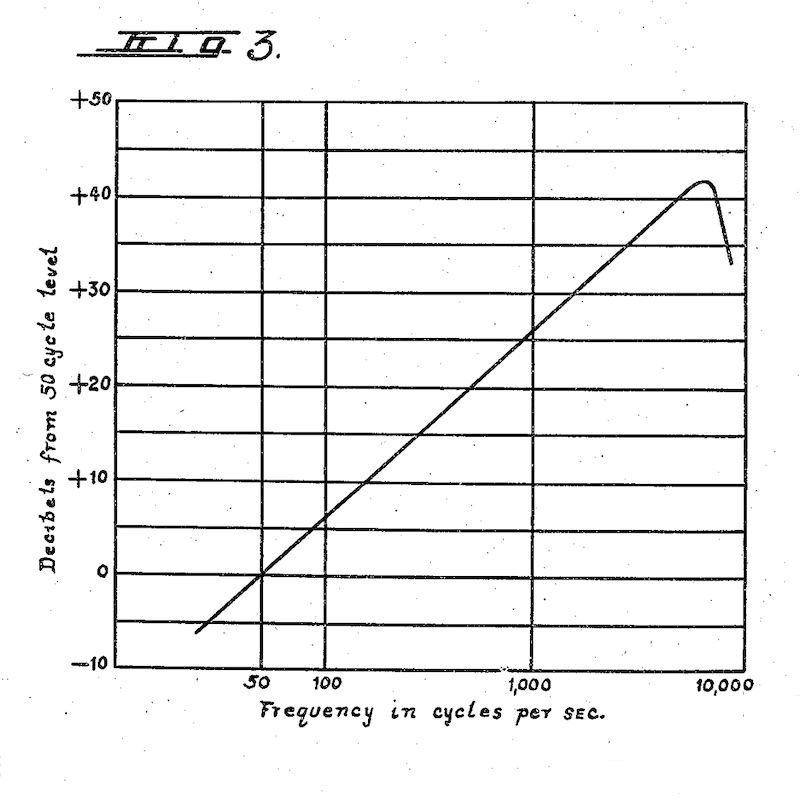

下のグラフが、1942年NAB規格で採用された、縦振動盤用(と横振動盤用)の録音カーブのプロットだね。縦振動盤のグラフは、横振動盤とはまったく違うスロープになってるね。

The graph below is a plot of the recording curves for the vertical / horizontal transcription records, as adopted in the 1942 NAB Standard. The graph for the vertical disc has a completely different slope than that for the lateral disc.

Western Electric Vertical/Lateral Recording Characteristics (1942 NAB), drawn on Nov. 23, 1942

Western Electric 社の縦振動/横振動用録音カーブ (1942 NAB vertical/lateral) をプロットした貴重なグラフ (Nicholas Bergh さん提供)

photo courtesy of Nicholas Bergh.

Pt.4 セクション 4.4.1 に載せた、Nicholas Bergh さん所有のホンモノの縦振動盤用再生イコライザの写真をみても分かる通り、本格的で大掛かりな構造の専用LCR録音再生イコライザが使われていて、特性も横振動盤とは全然違うスロープで急峻な高域プリエンファシスになってるね。これは確かに、現代の可変フォノイコでは正確な再生は無理で、当時の専用品を使うか、回路図を元に再生EQを作り直すかする必要がありそうだね。

As you can see from the photo of Nicholas Bergh’s real reproducing equalizer for vertical records in Pt.4 Section 4.4.1, a full-scale, large-scale structure dedicated LCR recording and reproducing equalizer is used, and its characteristics are completely different from those of lateral records in terms of slope and steep high-frequency pre-emphasis. It is certainly impossible for a modern variable phono preamps to reprodue this accurately, and it would be necessary to use a dedicated product of the time, or to rebuild the dedicated phono preamp based on the circuit diagram.

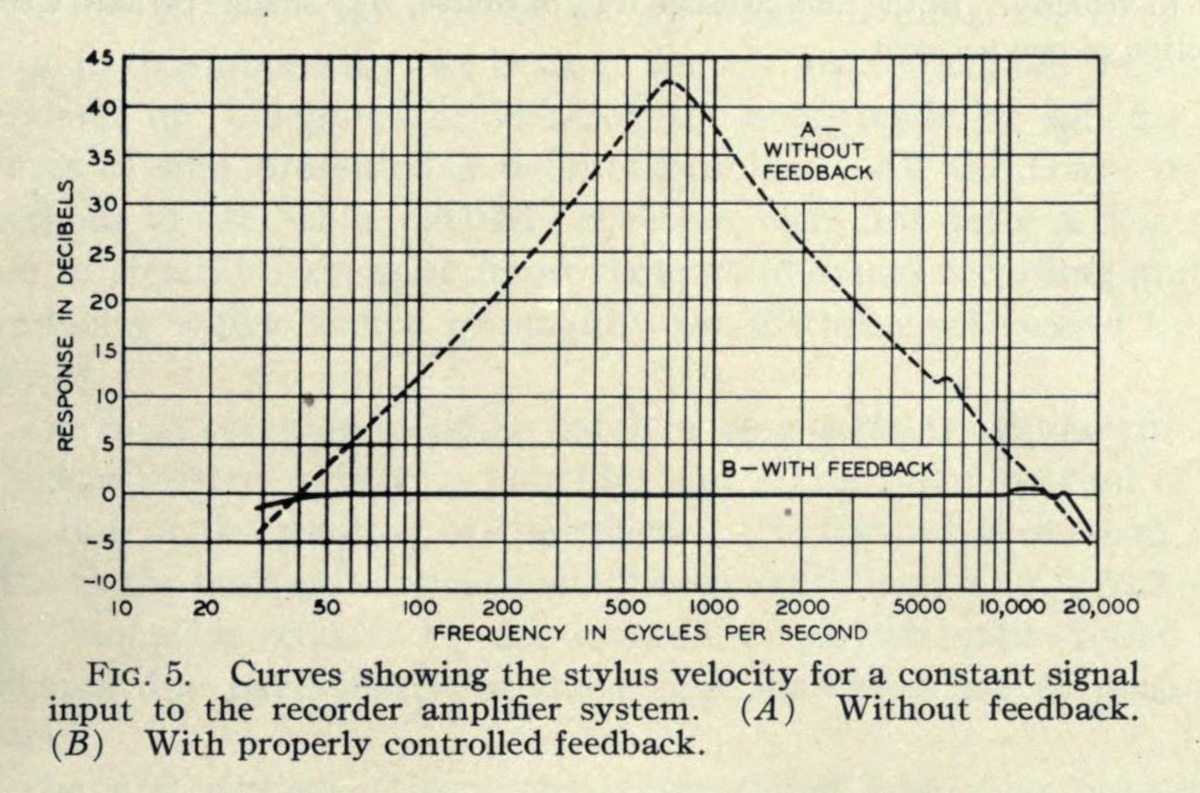

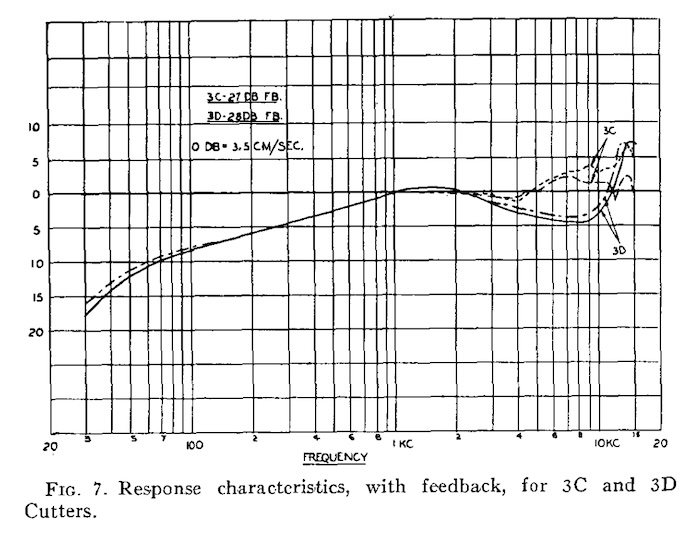

また 1937年には、モーショナルフィードバック の技術を用いたフラット特性の WE 縦振動盤用カッターヘッドが Bell Labs / Western Electric により発表され、史上初めて録音イコライザがカッターヘッドから完全に独立した例となった( Pt.4 セクション 4.4.2)。

In 1937, Bell Labs / Western Electric introduced a cutterhead for WE vertical discs with flat response characteristics using the motional feedback technique, which was the first example in history where the recording equalizer was completely independent of the cutterhead. ( Pt.4 Section 4.4.2)

source: “Recent Development in Hill and Dale Recorders”, Journal of the Society of Motion Picture Engineers, January 1938, p.103.

フィードバック回路が備わったカッターヘッドで、フラットな周波数特性での記録が可能に

横振動盤用のフィードバックカッターが米国で初お目見えしたのは1949年、本格的に使われ出したのは1950年代前半だから、10年以上も先駆けていたことになるし、当時の縦振動盤の技術は本当にすごかったんだね。

Feedback cutters for lateral records did not appear until the early 1950s — over ten years — so the technology for vertical records at the time was really astonishing, wasin’t it?

ベル研とストコフスキーの実験的ステレオ録音のエピソードも有名だね( Pt.5 セクション 5.1)。

Also famous is the episode of the experimental stereo recording between Bell Labs and Stokowski ( Pt.5 Section 5.1).

それにしてもベル研って本当に多くの研究開発で貢献していたんだね。

By the way, Bell Labs really contributed in countless research and development efforts.

ベル研は数えきれないほど貢献をしてきたよね。録音再生技術だけではなく、トーキー映画、ファクシミリ、テレビ送受信などもそうだね。さらにコンピュータの発展にも多大な貢献をしていて、リレー式コンピュータの開発、トランジスタやLSIの発明はもとより、ハミング符号やシャノンの暗号理論など、アルゴリズムの世界でも巨大な礎を作ったね。macOS や Linux の源流である UNIX、そしてプログラミング言語 C もベル研で開発されたものだね。

They definitely has made a lot of tremendous contributions. Not only in sound recording/reproducing technology, but also in many fields like “talkie” moving pictures, facsimile technology, television transmittion, and so on. They also made great contributions to the development of computers, including early relay computers, the invention of the transistor and LSI, researches on algorithms such as the Hamming code and Shannon’s theory of cryptography. UNIX (the origin of macOS and Linux) and the programming language C were also developed at Bell Labs.

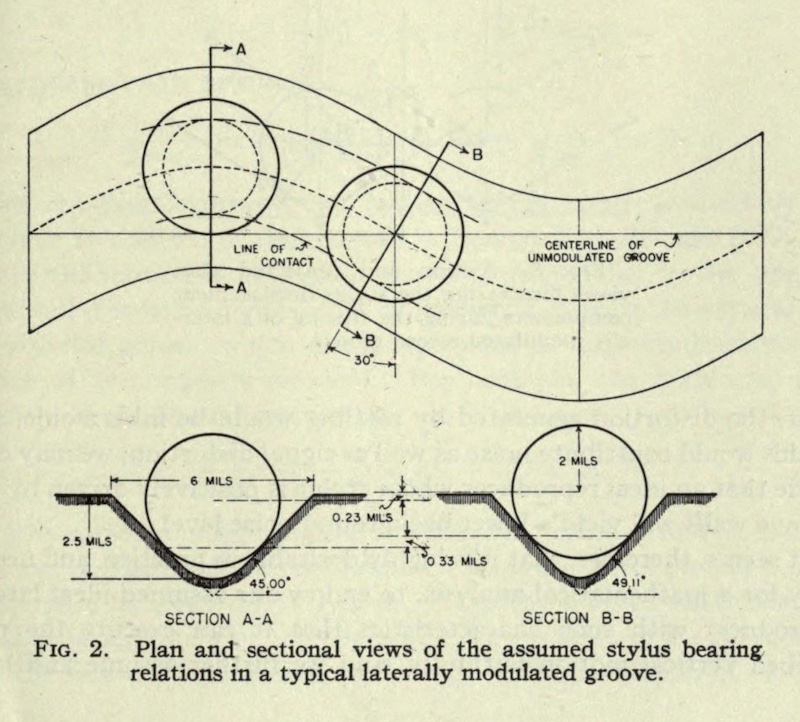

25.3.2 Pierce & Hunt’s Paper to Prove Superiority of Lateral Recordings

しかし、ハーバード大学の Cruft 研究所の John Alvin Pierce と Frederick Vinton Hunt 両氏により、横振動盤再生時に針が溝底につかず側壁でサポートされている場合、縦振動盤と比べて横振動盤の方が圧倒的に高調波歪が少なくて済むことが1938年の論文で示されたことにより、縦振動盤の優位性が否定されることとなった( Pt.6 セクション 6.2)。

However, a 1938 paper by John Alvin Pierce and Frederick Vinton Hunt of the Cruft Lab at Harvard University showed that when the needle is not on the groove bottom but supported by the side walls during lateral disc playback, the lateral disc has far less harmonic distortion than the vertical disc, negating the superiority of the vertical disc ( Pt.6 Section 6.2).

また両氏は、当時としては画期的に超軽針圧(HP6A は 5g、HP26A は 1g)で再生可能なピックアップ開発も行い、現代に繋がるレコード再生ピックアップ技術の礎 を築いた( Pt.6 セクション 6.3)。

They also developed pickups that could play at revolutionarily ultra-light needle pressure (5 grams for the HP6A, and 1 gram for the HP26A), laying the foundation for the record playback pickup technology that has continued to the present day ( Pt.6 Section 6.3).

このお二人の研究によって、レコード再生技術が圧倒的に進化したんだね。

The research of these two men has led to a tremendousadvancement in record reproducing technology, hasn’t it?

せっかく特許までとったのに、第二次世界大戦時に戦時研究従事のためこの分野から離れ、どこも訴えず、特許も放棄した、ってエピソードがシビレるよね。それにしても、1938年のJSMPE論文とElectronics誌解説記事は大興奮したよ。

It is fascinating to hear the story of how they left the field during World War II to engage in war research, never sued anyone, and abandoned their patents, even though they had already patented the technology. By the way, the 1938 JSMPE paper and the Electronics magazine article really excited me.

どこがそんなに凄いと思ったの?

What did you find so great about it?

だって、秘密主義が当たり前だった当時の蓄音機業界において、数学的・物理学的・科学的に正しく調査研究を行い、それが発表されていたこと。さらにその研究が、横振動盤の優位性を示し、同時に側壁サポートがのちのマイクログルーヴ盤による高品質再生の最も重要な礎の1つになっていること。初めて読んだ時。もう感動で震えが止まらなかったね。両氏には感謝と尊敬しかないよ。

Because, in the phonograph industry at that time, where secrecy was the norm, the research and studies were mathematically, physically, and scientifically appropriate, and they were published. Furthermore, that the research showed the superiority of the lateral discs, and at the same time, that the side wall support was one of the most important cornerstones of the later high quality reproduction with the microgroove discs. When I first read these, I couldn’t stop shaking with emotion. I have nothing but gratitude and respect for both of them.

その「側壁サポート」ってどういうこと?

What does that “side wall support” mean?

かつては、抗摩耗剤入りのザラザラした盤を重い針圧で再生していた。ということは、針がどんどん削れて針の先端が音溝の底に当たった状態で再生される。しかしこれだと、ピンチエフェクト(横振動記録であっても針が上下動する現象)への対応が不十分であり、満足な再生ができない、ってことだね。だから、軽針圧で、針の先端は音溝の底につかず、音溝の側壁と針だけが接してる状態であるのが、横振動盤再生には理想である、更には軽針圧であれば、抗摩耗剤抜きのスムーズな材質でレコードを作ればいいし、その方がもっと高品質な再生ができる、というリクツだね。

In the past, scabrous discs with abrasive agents were played back with heavy needle pressure. This meant that the needle would play back with the tip of the needle hitting the bottom of the groove as the needle was being scraped off. But this also means that the response to the pinch effect (phenomenon in which the needles moves up and down even tracing a lateral groove) is insufficient, and satisfactory playback is not possible. Therefore, Pierce & Hunt concluded that the ideal condition for lateral disc reproduction is that the needle tip does not touch the bottom of the groove, but only the side wall of the groove, under light needle pressure.

source: “Distortion in Sound Reproduction from Phonograph Records, J.A. Pierce and F.V. Hunt, Journal of the Society of Motion Picture Engineers, Vol. 31, No. 2 (August 1938), p.163

カッターヘッドの形状、進行方向と振幅方向の関係により、音溝に2点で接触する針先の場合、その通過する位置により上下動(ピンチエフェクト)が生じるため、縦方向の柔軟性(コンプライアンス)が必要

Laterally recorded groove creates vertical pinch effects, resulting the necessity of reproducing pickup’s vertical compliance.

針先は溝の底に当たらず、針は溝の側壁のみと接した状態で再生される、かつてはこれが当たり前ではなかったのはびっくり。

The needle tip does not hit the bottom of the groove, the needle is played back in contact only with the side walls of the groove… It is really surprising that this was not the norm in the past.

そうだね。けど Pierce & Hunt の研究によって広く知られるようになり、戦後くらいにはすでに一般的な知見となっていたそうだね。

Yes it is. I heard that it became widely known through the research of Pierce & Hunt, and was already a common knowledge in the postwar period.

なるほど、本当にお二人のおかげで今のレコード再生技術があるわけだね。

I see, so it really is thanks to the both of them that we have the record playing technology we have today.

どこのメーカにもレーベルにも所属しない純粋な研究者だったから可能だったんだろうね。それと、この両者の研究がなければ、縦振動盤は更に生きながらえかもしれない。そうすると、マイクログルーヴ盤登場やステレオLP誕生がもっと遅れていたり、あるいは今とは違うレコード再生の世界になっていたかもしれない。そう考えると、胸アツだね。

I guess it was possible because the both of them were pure researchers who were not affiliated with any manufacturer or label. Also, without the research of Pierce & Hunt, the vertical discs might have survived further. If so, the appearance of the microgroove discs and the birth of the stereo LP might have been delayed, or the world of record and its reproduction might have been different from what it is today. Isn’t it very exciting just to think so?

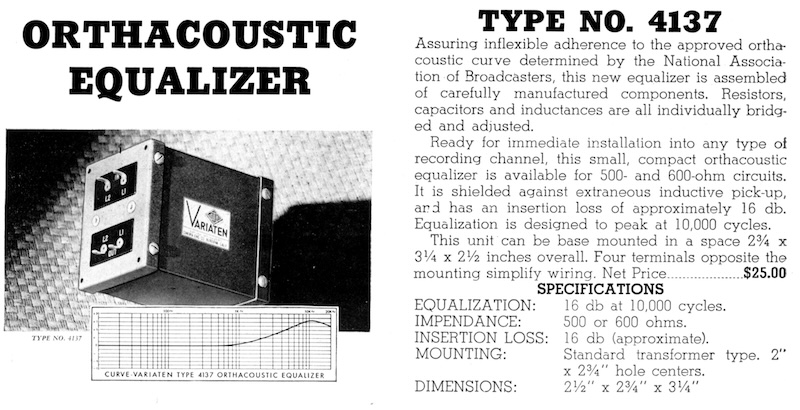

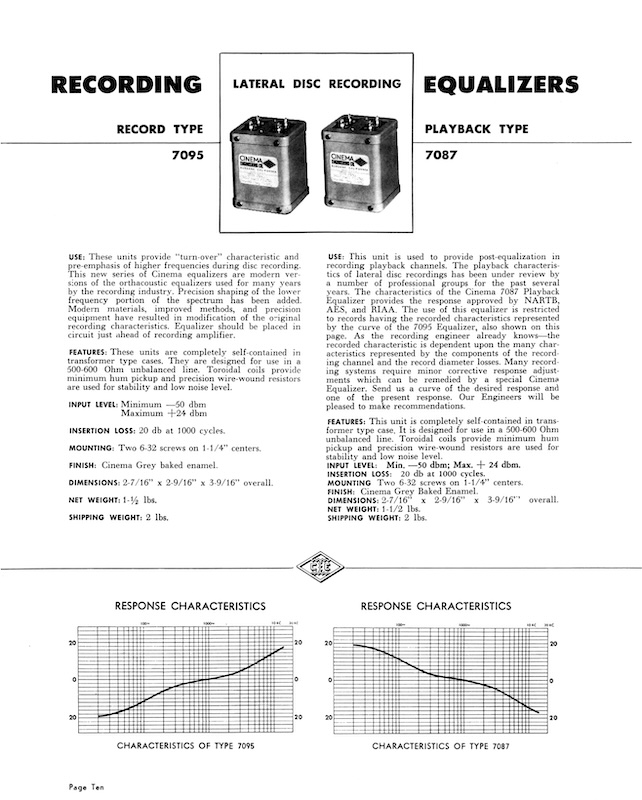

25.3.3 Lateral Electrical Transcription Discs and “Orthacoustic”

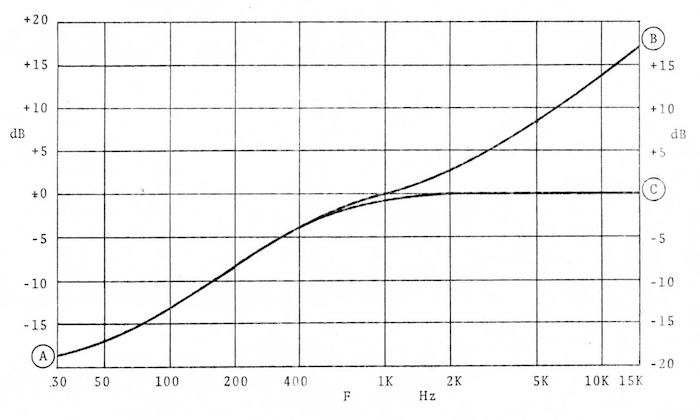

横振動記録のトランスクリプションも多く流通し、当時の民生用レコードより高音質・長時間であったが、録音再生カーブがレーベルによってまちまちであり、同時に企業秘密となっていたため、ラジオ局は正しい再生に苦慮していた。そんな中、RCA Victor / NBC が、横振動トランスクリプション盤用に Orthacoustic 特性カーブ を開発し、1939年に発表した( Pt.5 セクション 5.2.1)。

Lateral transcription discs were also widely distributed and had better sound quality and longer playing time than the consumer records of the time, but the recording / reproducing curves varied from label to label, and at the same time were a trade secret, so radio stations struggled to reproduce them correctly and properly. Under such circumstances, RCA Victor / NBC developed the Orthacoustic characteristics curve for lateral transcription records and announced it in 1939 ( Pt.5 Section 5.2.1).

source: Orthacoustic Transcriptions Ad, ATE Journal, December 1939, p.0

ATE Journal 1939年12月号に掲載された Orthacoustic トランスクリプションの広告

ラジオ局用トランスクリプション盤の世界でも、当然横振動盤が多く使われていたんだね。

Naturally, lateral discs were widely used in the world of electrical transcription records as well.

ラジオで民生用78回転盤もトランスクリプション盤もかける場合、再生機器を共通化できるからね。また、トランスクリプション盤を出すレーベルでも、縦振動の Western Electric 派でないところもあったわけで。実際のところは、ラバーラインレコーダの時と同様、Bell Labs / Western Electric の縦振動盤特許を回避するためだったようだね。

When playing both consumer 78 rpm discs and transcription discs on the radio, it was possible to share the same playback equipment. Also, there were some labels that produced transcription discs that were not Western Electric groups with vertical discs. The possible truth would be, as with the “rubberline recorders”, that the adoption of lateral recordings for transcription records was to avoid the Bell Labs / Western Electric’s patent.

この Orthacoustic カーブの高域プリエンファシスは、当時開発中のFM放送で実験用に使われていた 100μs高域プリエンファシス を援用したものであった(のちに米国FM放送のプリエンファシスは75μsと定められた)( Pt.5 セクション 5.2.3)。

The high-frequency pre-emphasis of the Orthacoustic curve was based on the 100μs high-frequency pre-emphasis used experimentally in FM broadcasts under development at the time (the pre-emphasis for U.S. FM broadcast was later set at 75μs) ( Pt.5 Section 5.2.3).

へぇ、ディスク録音カーブのプリエンファシスは、FMラジオのプリエンファシスからヒントを得ていたんだね。

That’s interesting. The pre-emphasis of the disc recording curve was inspired by the pre-emphasis of FM radio!

絶対そうだ、という証拠があるわけではないんだけど、FM放送の開発ペースと、ディスク録音でプリエンファシスが導入された時期が近いこと、また、採用された時定数が100μs/75μs/50μsと、FMで使われていたものと全く一緒であることから、以前からそのように考えられているね。

There is no proof that this is absolutely true, but it has long been tought to be the case because the pace of development of FM broadcasting is close to the time when pre-emphasis was introduced in disc recording, and the time constants used are 100μs / 75μs / 50μs, exactly the same as those used in FM.

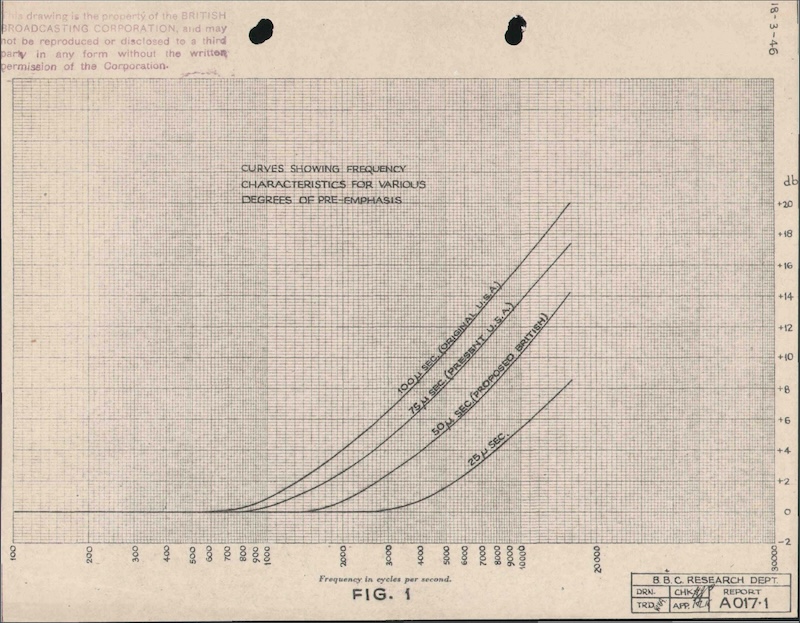

source: BBC Research Department: Frequency Modulation (Report No. A.017, Serial No. 1946/4).

1946年4月にBBC研究部門が発行したレポートより。FM放送における高域プリエンファシスのグラフ。

“100μsec (original U.S.A.)”, “75μsec (present U.S.A.)”, “50μsec (proposed British)” とある。

ところで、さらっと出てきたけど、「μs(マイクロ秒)」って何を表してるの?

By the way, just out of curiosity, what does “μs (microseconds)” stand for?

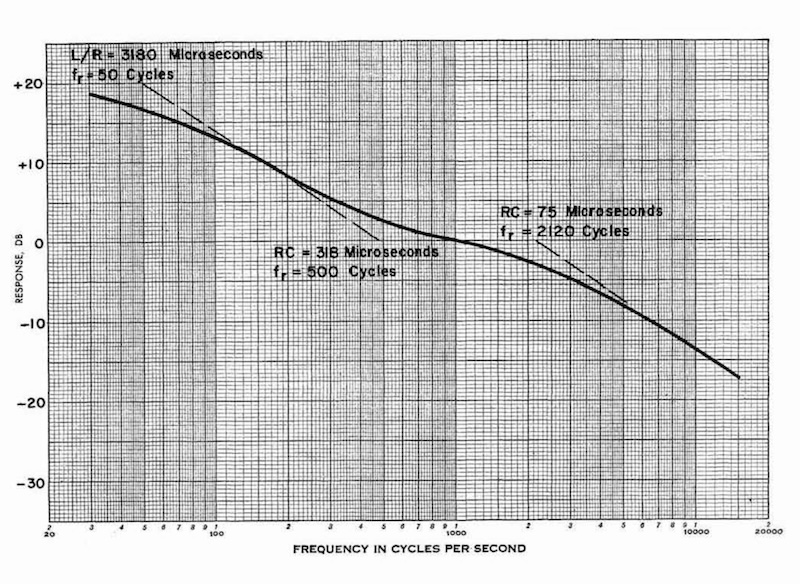

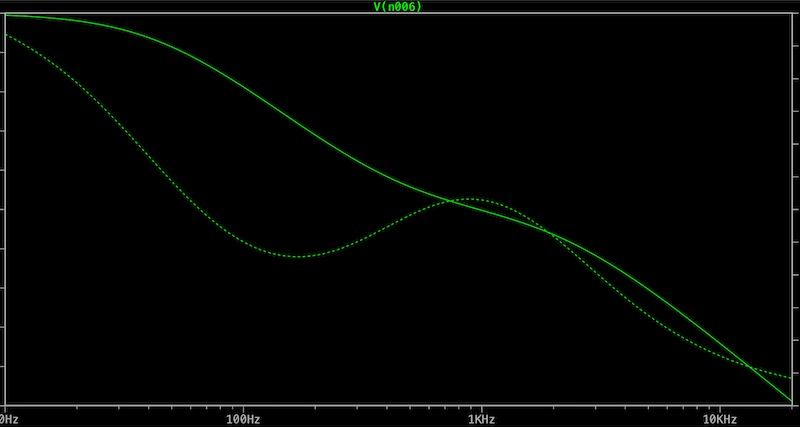

電子回路における 時定数 の単位だね。RL回路(抵抗とコイル)や RC回路(抵抗とコンデンサ)を使った信号処理系において、周波数応答の特徴を表すために用いられる。例えば、「ターンオーバー 500Hz」(500Hz 以下は定振幅、500Hz 以上は定速度)は、下の計算式のように時定数が 318μs となる。

It is a unit of time constant in electronic circuits and is used to characterize the frequency response in signal processing systems using RL (resistor and inductor) or RC (resistor and capacitor) circuits. For example, “turnover 500Hz” (constant amplitude below 500Hz and constant velocity above 500Hz) has a time constant of 318μs, as shown in the formula below.

なるほど、正直よくわからないけど、ディスク録音再生カーブの特性を正確に表現するパラメータってことかな。

Okay, I honestly don’t understand it, but I guess it’s a parameter that accurately represents the characteristics of the disc recording / reproducing curves, right?

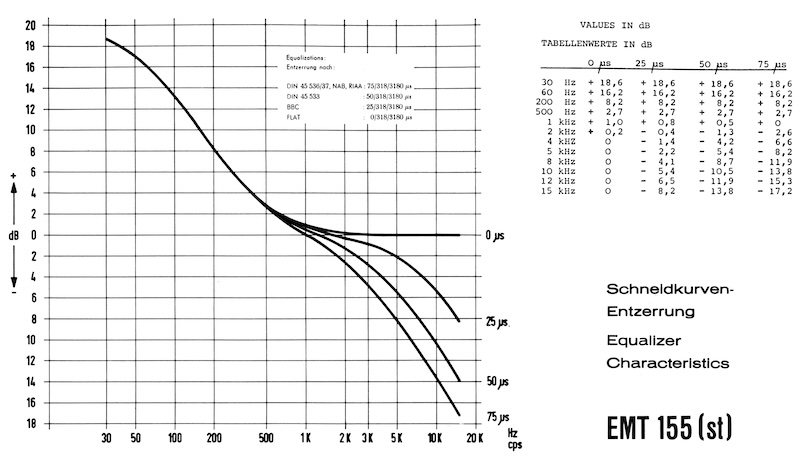

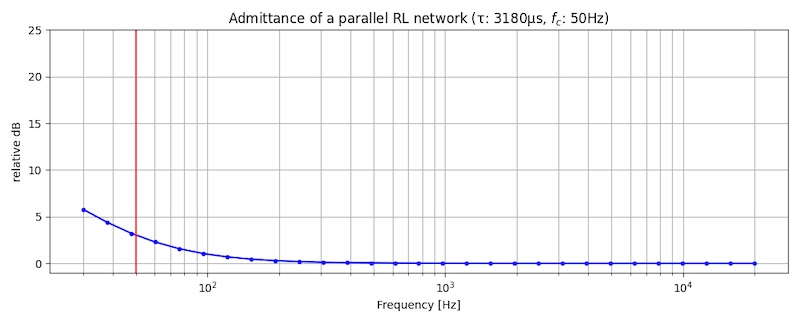

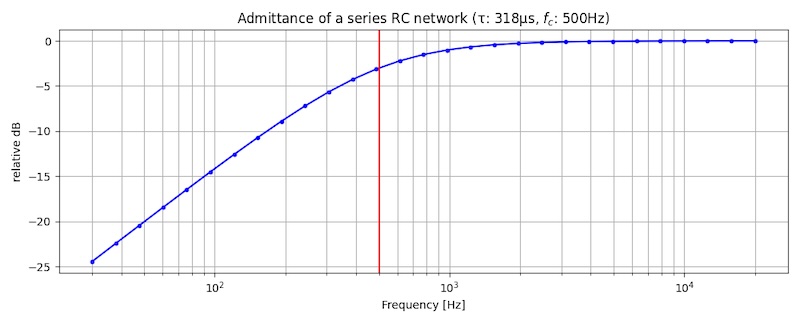

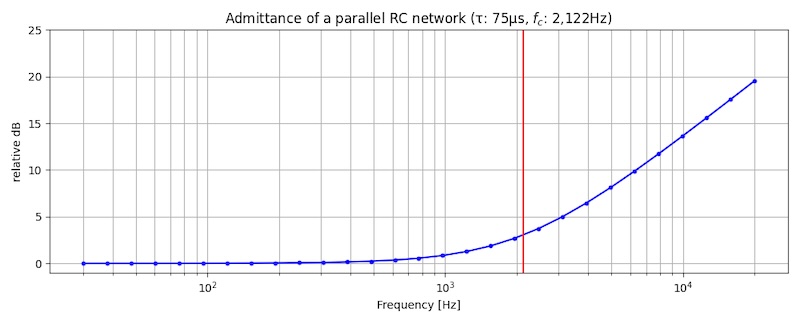

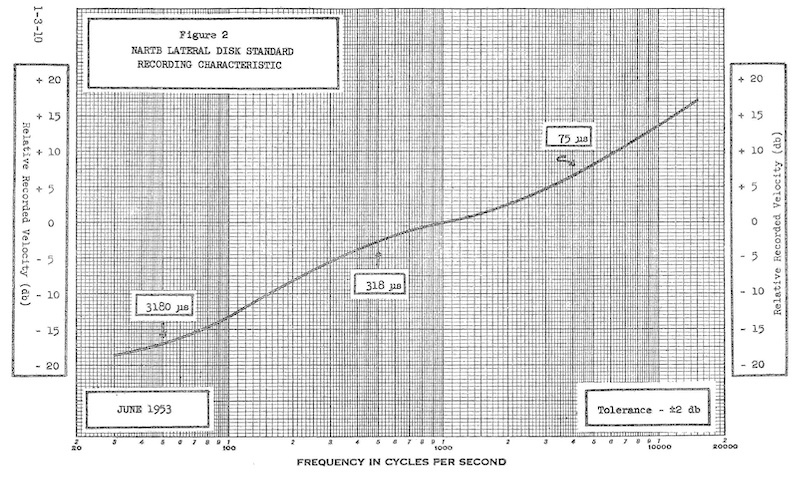

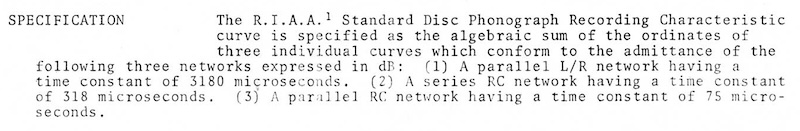

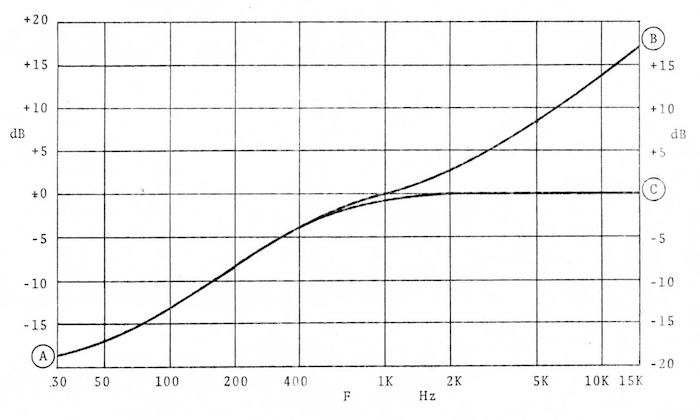

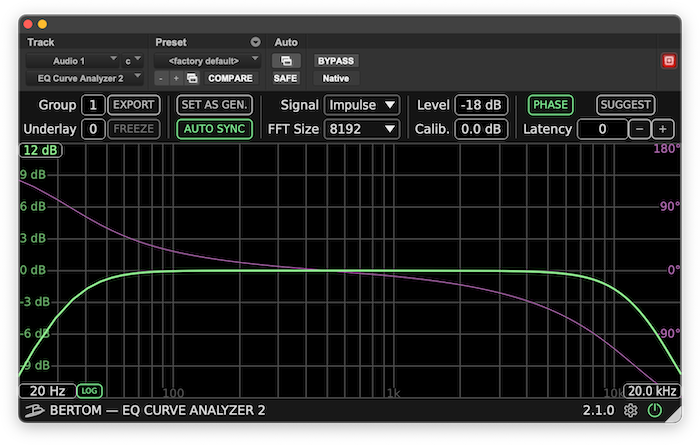

そういうことだね。例えば、現在の RIAA 録音特性を時定数で表すと、ベースシェルフは 3,180μs、ターンオーバーは 318μs、高域プリエンファシスは 75μsとなり、それぞれグラフで表現すると以下のようになるね。この3つを合成したものが RIAA 録音特性ってことだ。

That’s what I mean. FOr example, if we express the current RIAA recording characteristics in terms of time constants, the bass shelf is 3,180μs, turnover is 318μs, and high-frequency pre-emphasis is 75μs, each of which can be graphically represented as follows. The RIAA recording characteristics are the composite of these three.

Admittance of a parallel RL network (τ: 3,180μs, fc: 50Hz)

graph plotted using PySpice and Matplotlib.

時定数3,180μs、ターンオーバー周波数 50Hz の並列RL回路のアドミタンス

Admittance of a series RC network (τ: 318μs, fc: 500Hz)

graph plotted using PySpice and Matplotlib.

時定数318μs、ターンオーバー周波数 500Hz の直列RC回路のアドミタンス

Admittance of a parallel RC network (τ: 75μs, fc: 2,122Hz)

graph plotted using PySpice and Matplotlib.

時定数75μs、ターンオーバー周波数 2,122Hz の並列RC回路のアドミタンス

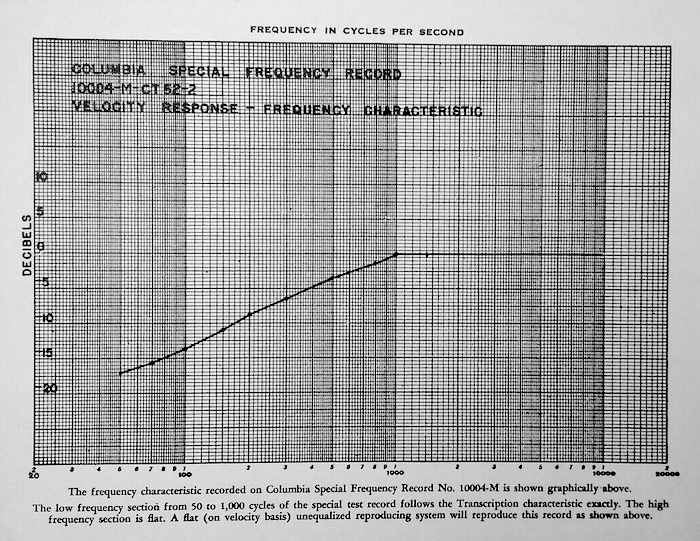

また、78回転より遅い33⅓回転であったために、ランブルノイズやレコードの反りに敏感であり、それに対応すべく、Orthacoustic はベースシェルフ(低域プリエンファシス)を採用した最初の例となった( Pt.5 セクション 5.2.3)。

Also, because the transcription records were 33⅓ rpm (slower than 78 rpm), it was sensitive to rumble noise and record warping. Orthacoustic was the first to adopt a bass shelf (low-frequency pre-emphasis) to deal with this problem ( Pt.5 Section 5.2.3).

へぇ、Columbia LP カーブや RIAA カーブでお馴染みのベースシェルフは、Orthacoustic トランスクリプション盤の時代に初めて採用されたんだね。

Wow, the bass shelf familar from the Columbia LP curve and RIAA curve was first used in the era of Orthacoustic transcription discs.

78回転から33⅓回転と一気に線速度が遅くなると、ランブルノイズ(ゴロ)が目立ちやすくなるからだね。関係ないけど、LP時代のアンプにもランブルノイズ低減の目的で「サブソニックフィルタ」がついているものがあったよね。

That’s because rumble noise becomes more noticeable when the line speed (linear velocity) slows down from 78 rpm to 33⅓ rpm. On an unrelated topic, some LP-era amplifiers also had “subsonic filters” to reduce rumble noise, right?

Orthacoustic における 500Hz ターンオーバーは、依然としてカッターヘッド自体の特性、および 500Hz ターンオーバーに揃える補正回路、の合計で実現されていた。結果として、Orthacoustic 録音カーブ全体は、カッターヘッドの特性 + それを 500Hz ターンオーバーに微調整する回路 + 100μsプリエンファシスおよび3,180μsベースシェルフの回路、という構成であった( Pt.5 セクション 5.2.3)。

The 500Hz turnover in Orthacoustic was still achieved by the sum of the characteristics of the cutterhead itself, and the correction circuitry to adjust it to 500Hz turnover. As a result, the entire Orthacoustic recording curve consisted of the characteristics of the cutterhead + the circuitry tofine-tune it to 500Hz turnover + 100μs pre-emphasis and 3,180μs bass shelf circuitry ( Pt.5 Section 5.2.3).

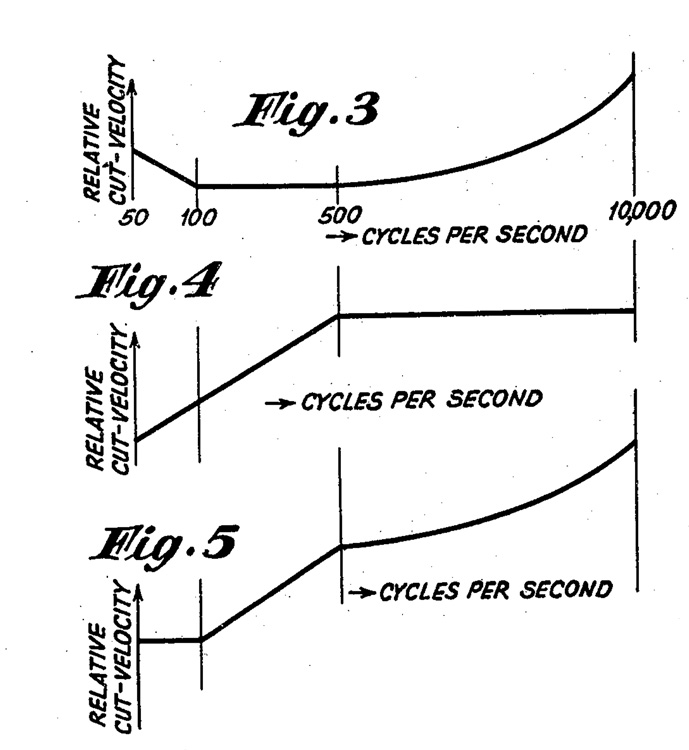

source: “Sound Translating System”, US Patent 2,286,494, Roland A. Lynn & Jarrett L. Hathaway, 1940

Pt. 5 で紹介した、Orthacoustic の特許文書より

Fig.4 がカッターヘッドの電気機械的記録特性(追加で補正回路を使う場合もあり)、

Fig.3 が Orthacoustic プリエンファシスフィルタ(録音イコライザ)特性、

Fig.5 が両者を合計した最終的な記録特性

Fig.4: Cutterhead’s Frequency Response (sometimes accomplished with additional circuits)

Fig.3: Frequency Response of the Orthacoustic pre-emphasis (recording) filter

Fig.5: Final recording characteristics of Orthacoustic, a combination of Fig.4 and Fig.3

この頃もまだ、カッターヘッドの特性がフラットではなかったから、ターンオーバー部分はカッターヘッドが担っていたんだね。

Even at this time, the cutterhead characteristics were not yet flat, so the cutterhead was still responsible for the turnover portion.

まだ横振動盤用のモーショナルフィードバックカッターが存在しなかったからね。だから以前からの伝統に則った方法で録音カーブが設定されていたわけだね。

THere was no motional feedback cutter for lateral cut records yet. So the recording curves had to be set in the traditional way.

この Orthacoustic は、本格的なLCR回路ではなく廉価なRC回路でも「±2dBの誤差の範囲内で」再生可能にすることを念頭にして定義されたものであった( Pt.5 セクション 5.2.3)。これらの技術詳細は推奨回路図込みで公開されたが、企業間の秘密主義が一般的だった当時としては貴重なものであった。

This Orthacoustic was intended to allow reproductin “within ±2dB deviation” with inexpensive RC circuits rather than full-scale LCR circuits ( Pt.5 Section 5.2.3). These technical details were published with recommended circuit diagrams, which were valuable at a time when secrecy among companies was common.

LCR 回路と RC 回路だと周波数特性や位相に微妙に差が出てしまうけど、当時は ±2dB は許される誤差だった、ってことかな。

The LCR and RC circuits have subtle differences in frequency response and phase, but at the same time, ±2dB was an acceptable deviation.

まぁそういうことだね。LCR 回路は、L つまりコイルにコストがかかり、同時に特性を安定させるのが非常に難しいから、歩留まりも悪く、どうしても高価になってしまう。RCA Victor / NBC は、廉価に製造できる RC 回路でも再生可能、と明言することで、気軽に参入可能であることをアピールした、すなわち Orthacoustic の普及を狙っていたのかもしれないね。実際、Orthacoustic の解説論文 (1939) 中でも「録音再生特性の実現を、可能な限りシンプルかつ廉価に行いたい」と書かれてるんだ。

Well, that’s what I mean. LCR circuits are expensive because of the cost of the L (coil) and the difficulty of stabilizing the characteristics, which also results in low yields and high prices. RCA Victor / NBC might have been trying to promote Orthacoustic by stating that RC circuits, which can be manufactured inexpensively, can also be used for reproduction. As a matter of fact, the technical paper (1939) on Orthacoustic reads: “a desire to achieve the recording and compensating characteristics as simply and economically as possible”.

なるほどね。低コストであれば、採用してくれるところも増えるしね。

I see. If it were low-cost, there would be more studios and radio stations willing to adopt it.

±2dBにした他の理由として、当時は再生用ピックアップの応答特性も千差万別だったから、というのもあるね。そのほかには、近似した録音特性を採用しているスタジオであれば、±2dB の範囲内だから録音イコライザの改造や新調にコストをかけず現状維持でもオッケー、というのも狙ってた可能性も考えられるね。その緩さ、あるいは柔軟性のおかげで、1942年NAB規格として Orthacoustic 特性が採用されたのかもしれないね。

Another possible reason for the ±2dB deviation is that the response characteristics of playback pickups varied widely at that time. Another possibility is, if the studios employed a recording characteristic that was close to the Orthacoustic within the ±2dB deviation, the studios could have maintained the recording equalizers as they were, without the cost of modifying or replacing the equalizers. This looseness or flexibility may have led to the adoption of Orthacoustic characteristics as the 1942 NAB Standard.

25.4 Pre-emphasis with consumer 78rpms

高域プリエンファシスの適用が、米国の民生用レコードにも進んでいった流れについて。そして、ワックス盤ではなくラッカー盤にカットする、アセテート録音機が登場し、オープンリールテープ登場までの間、即時再生用のディスク録音が徐々に普及した流れも。1930年代〜1940年代前半あたりの話です。

Next is the trend toward the application of high-frequency pre-emphasis to consumer records in the United States, as well as the trend toward the gradual spread of instantaneous disc recorders, until the advent of reel-to-reel tape recorders. The timespan is approximately from the 1930s to the early 1940s.

25.4.1 RCA Victor’s Compensator Circuit for Home Domestic Recordings (1940)

放送局用トランスクリプション盤に続き、民生用レコード(78回転盤)のカッティングにおいても、500Hzターンオーバー特性のカッターヘッドの後段への自社製高域プリエンファシス回路の追加が1930年代末頃から行われるようになった。ただし、ベースシェルフの採用はまだだった。

Following broadcast transcription records, the addition of in-house high-frequency pre-emphasis circuits to the rear stage of the cutter head with 500Hz turnover characteristics began in the late 1930s for cutting of records for consumer use (78 rpm discs). However, the bass shelf had not yet been adopted.

RCA Victor の1940年当時の社内技術文書で回路図とグラフが現存しており、当時の RCA Victor の民生用78回転レコードの高域プリエンファシスは LCR 回路ではなく RC 回路で構成されていることが確認できる( 2022 ARSC Conference における Nicholas Bergh 氏の発表スライド、ARSC 会員のみ閲覧可能)( “Master Reference Book for Disc Recording”, RCA Manufacturing Company, Inc., February 1940)。

RCA Victor’s internal technical documents from 1940 with surviving schematics and graphs confirm that the high-frequency pre-emphasis circuit for RCA Victor’s consumer 78rpms at that time consisted of an RC circuit, not an LCR circuit ( slides presented by Nicholas Bergh at the 2022 ARSC Conference, available only to ARSC members) ( “Master Reference Book for Disc Recording”, RCA Manufacturing Company, Inc., February 1940).

他レーベルにおいてもおそらくは、同様に高域プリエンファシス追加の取り組みが行われていたと考えられる。しかし、技術資料がほとんど残っていないため、または公になっていないため、正確なパラメータなどは不明である。よって、出回っているカーブ一覧表は試聴による主観判断によるものがほとんどであると考えられる。

Other labels probably made similar efforts to add high-frequency pre-emphasis, but since few technical documents remain or have been made public, the exact parameters are unknown. Therefore, it is believed that most of the curve lists that are available are based on subjective judgements based on through listening.

25.4.2 Instantaneous Disc Recorders and Cutterhead Characteristics

1934年の Presto 6D アセテート録音機、1941年の Presto 6N アセテート録音機は大ヒットとなり、レコード制作目的のフィールドレコーディングに用いられたほか、熱狂的なアマチュアにも録音手段がもたらされることとなった( Pt.6 セクション 6.1)。Alan Lomax による有名な膨大なフィールドレコーディングも Presto 6D で行われた。

Presto’s instantaneous disc recorders, such as Presto 6D (1934) and Presto 6N (1941) were big hits, used for field recording for record production purposes, and also providing a means of recording for enthusiastic amateurs ( Pt.6 Section 6.1). Alan Lomax’s famous voluminous field recordings were also made on the Presto 6D.

そういえば、「アセテート盤」ってよく呼ばれるけど、正確にはニトロセルロースをアルミニウム円盤に塗布した「ラッカー盤」が正確なんだよね。

Oh, by the way, they often call it an “acetate disc”, but the exact term is “lacquer disc”, which is an alminium disc coated with cellulose nitrate.

上で紹介した Bell Labs / Western Electric の縦振動盤が当初はセルロースアセテート製だったから、または最初期のラッカー盤はセルロースアセテート製だったから、そのコトバだけが残ったという説もあるみたいだね( Pt.6 セクション 6.1)。一方、少なくとも日本では、即時録音再生メディアとして「アセテート盤」、プレスマスターとして「ラッカー盤」、と区別して使用しているかもしれないね。

There seems to be a theory that, because the vertical records by Bell Labs / Western Electric (mentioned above) was initially made of cellulose acetate, or because the very early lacquer discs were made of cellulose acetate, the word “acetate” remained for naming “lacquer” ( Pt.6 Section 6.1). On the other hand, at least in Japan, cellulose nitrate discs may be called as “acetate discs” when used for instantaenous recording; “lacquer discs” when used for press masters.

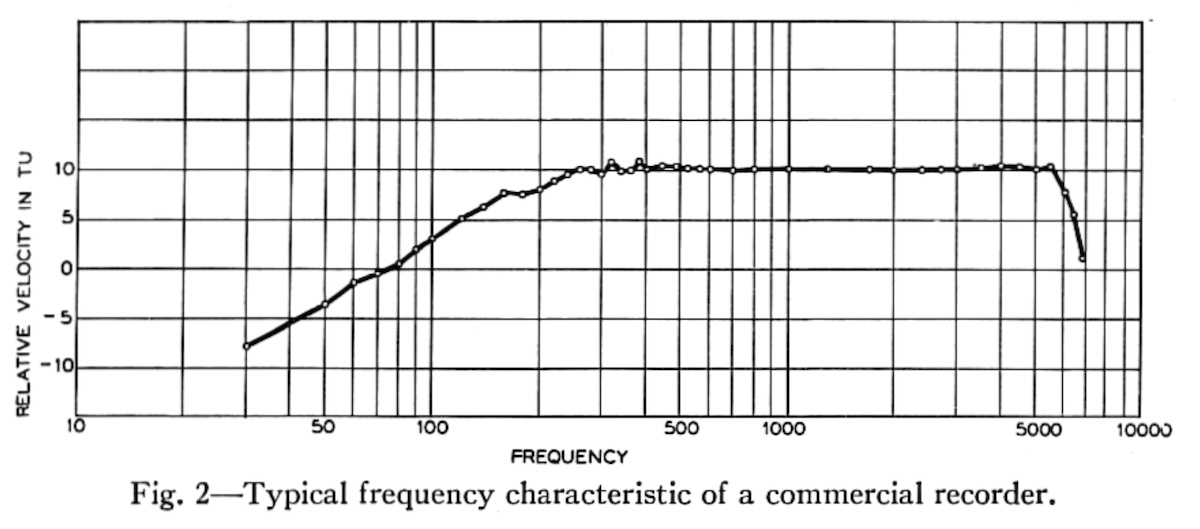

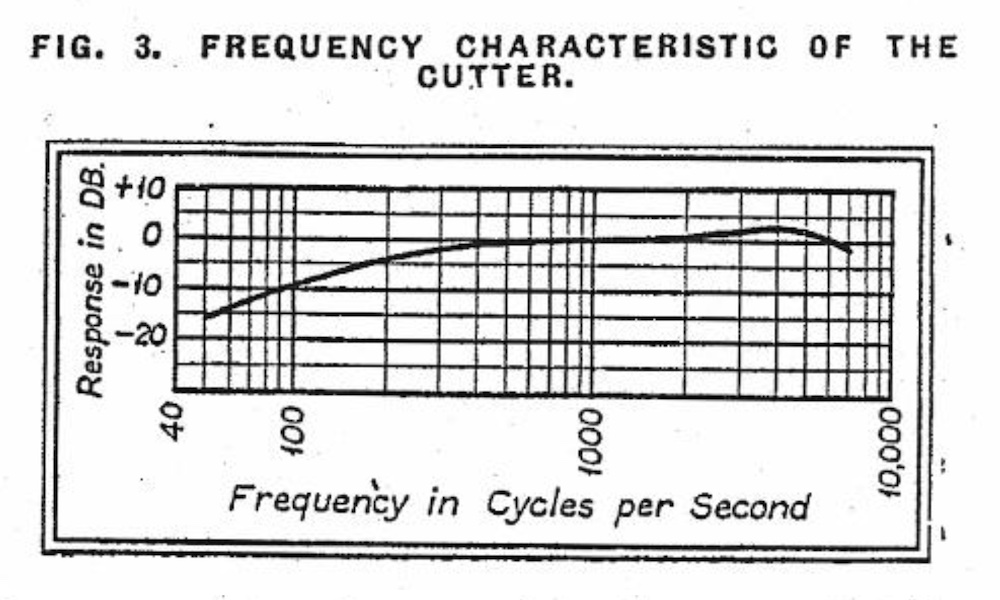

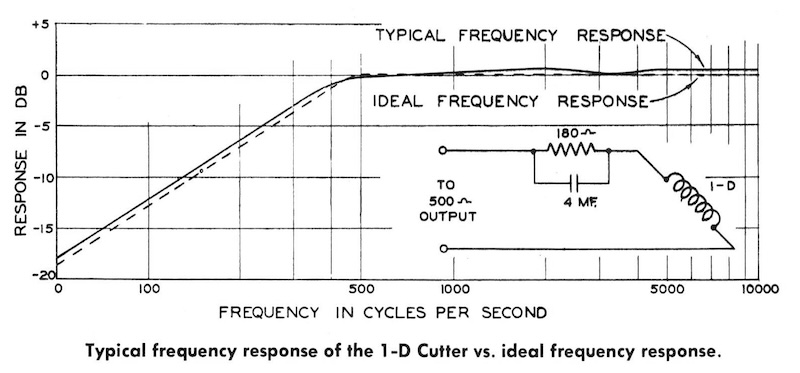

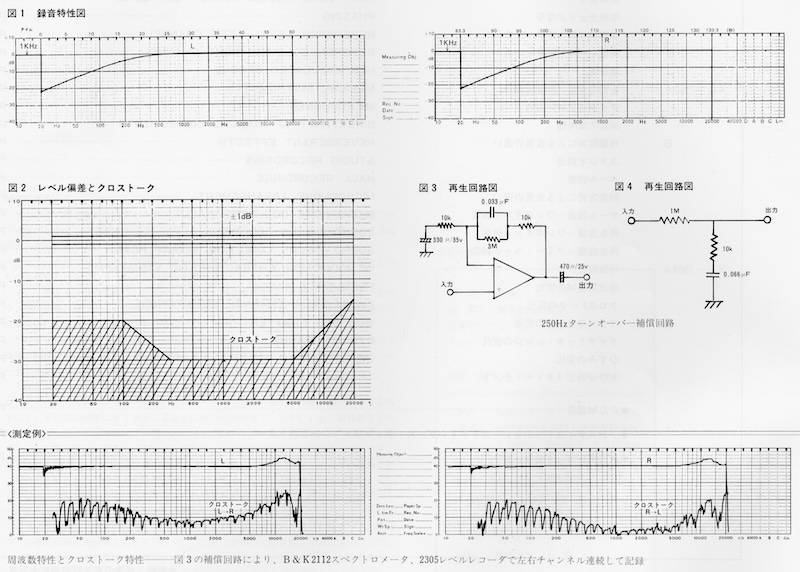

このアセテート録音機用のカッターヘッド、Presto 1-B / 1-C / 1-D は、民生用レコードカッティング用にも広く使われた。その応答特性や補正回路も資料が多く残されており、民生用レコード用スタジオ録音システムと同様、カッターヘッドの特性に補正回路を加えて500Hzターンオーバーを実現し使用されていたことが確認できる( Pt.6 セクション 6.1.1)。アマチュアやセミプロは、ターンオーバー500Hz、高域プリエンファシスなし、という録音特性を使っていた。

The Presto 1-B / 1-C / 1-D cutterheads for instantaneous disc recorders were also widely used for consumer record cutting. Many documents have survived that show the response characteristics and correction circuits of the Presto cutterheads, confirming that they were used in the same way as studio recording systems for consumer records, with a 500Hz turnover achieved by adding a correction circuit to the cutterhead characteristics ( Pt.6 Section 6.1.1). Most amateurs and semi-professionals used recording characteristics with a turnover of 500Hz and no high-frequency pre-emphasis.

なるほど、カッターヘッドの裸特性は 500N-FLAT じゃなかったんだね。

Hmmm, the bare characteristic of the cutterhead was not 500N-FLAT.

source: “An Instantaneous Recording Head”, George J. Saliba, Communication and Broadcast Engineering, March 1937 (archived at World Radio History), p.8

Presto チーフエンジニアによる、1-B カッターヘッドについての解説記事

1-B technical article, authored by the Presto’s chief engineer

そうだね。これに簡単な補正回路を足して、500N-FLAT を達成していたんだね。

That’s right. Then a simple correction circuit was added to achieve 500N-FLAT.

Typical frequency response of the 1-D Cutter (with a simple RC network)

source: Presto Recording Corp. 1948 Catalog, p.19

簡単なRC回路で補正してターンオーバー500Hz、6dB/オクターブスロープを実現

米国の民生用レコードレーベルは、社外秘の独自の録音特性を使っていたと言われているが、RCA Victor などごく一部のレーベル以外、なんの資料も残っていない(または公になっていない)ため、確認できない。ただ、民生用レコードのカッティングで Sculley カッティングレースと Presto カッターヘッドを組み合わせていたスタジオは多く確認されている( Pt.6 セクション 6.1.2)。

It is said that U.S. consumer record labels used their own proprietary recording characteristics that were kept secret from the public, but this cannot be confirmed because no documentation has survived (or is not publicly available), except for a few labels such as RCA Victor. However, many studios are known to have used a combination of Sculley cutting lathes and Presto cutterheads for cutting consumer records ( Pt.6 Section 6.1.2).

さらに、特にクラシック音楽では、ターンオーバーを最大 1,000Hz にまでひきあげ、記録可能な周波数帯域を競っていた一部のレーベルがある、という当時の噂話、さらには 3kHz 近辺を意図的に盛り上げた録音をするレーベルを評して「高域を強調すれば廉価な再生機でキンキン聞こえて良い、というインチキハイファイが始まった」と苦言を述べる1944年当時の評論記事もある( Pt.9 セクション 9.2.1)。しかし、こういった録音特性について公になった情報はなにもなく、また当時の民生用再生機器にはせいぜいトーンコントロールやスクラッチノイズ低減用の高域アッティネータ程度しか存在しなかったため、正しい特性で再生する以前の問題であった。

In addition, it is possible to confirm the rumor of the time that some labels were competing for recordable frequency bandwidth by raising the turnover to a maximum of 1,000Hz, especially for classical music. Furthermore, there is an article from 1944 in which a critic complained about some labels that intentionally boosted the frequency range around 3kHz, saying “‘phony high fidelity’ with a spurious brilliance that sounded ‘nice’ on the cheap sets” ( Pt.9 Section 9.2.1). However, there was no public information about such recording characteristics, and consumer playback equipment at that time had only tone controls and a high-frequency attenuator to reduce scratch noise at best. So the situation at the time was far from “high fidelity with correct response characteristics”.

この話がホントなのかどうかは確認のしようがないけど、一部のレーベルではかなりテキトーに録音特性をいじってたってことなのかな。

There is no way to confirm whether this story is true or not, but I wonder if it means that some labels were actually tweaking the recording characteristics in a very unorthodox way.

そうだね。業界での標準的な規格もなかった時代、再生機器側も十分な対応がとれなかった時代、民生用では忠実再生なんてまだ夢だった時代だからね。ある意味では、このターンオーバーを競っていたさまは(もし本当にそんなことが行われていたのであれば)、20世紀末〜21世紀初頭の「ラウドネス・ウォー」(音圧競争)に似てる気もするね。

It may be so, or may not. Anyway, it was a time when there were no industry standards, when playback equipment could not adequately respond, and when faithful reproduction was still a dream for consumer use. In a sense, this competition for the turnover (if it really existed) seems similar to the “loudness wars” of the late 20th and early 21st centuries.

一方、英国や欧州では、先述の通り 250Hz ターンオーバー、高域プリエンファシスなし、という録音特性が、比較的後年まで一般的であった。

On the other hand, in the U.K. and Europe, the recording characteristics of 250Hz turnover and no high-frequency pre-emphasis, as mentioned above, were common until relatively later years.

25.5 Piezoelectric Pickups and its Reproducing Characteristics

定速度特性のマグネットカートリッジとは異なる定振幅特性を備えた圧電式カートリッジが登場、ジュークボックスや廉価な民生用再生機器で一気に普及した流れについて。ふたたび1930年代〜1940年代前半あたりの話です。

This section deals with the emergence of piezoelectric pickups with constant amplitude characteristics that differ from magnetic pickups with constant velocity characteristics, and a trend that quickly spread to jukeboxes and inexpensive consumer playback equipment. The timespan is, again, approximately from the 1930s to the early 1940s.

25.5.1 Birth of Piezoelectric Pickups

1930年代前半にクリスタルカートリッジに代表される圧電式カートリッジが登場、ジュークボックス市場の発展とあわせるかのように一気に普及が進み、民生用の再生システムで長らく主流となった( Pt.7 セクション 7.1)。

In the early 1930s, piezoelectric pickups, as represented by crystal cartridges, were introduced, and their use spread rapidly, as did the development of the jukebox market, and they remained the mainstream in consumer playback systems for a long time ( Pt.7 Section 7.1).

そういえば、あの Shure って、元々は圧電式装置を積極的に開発していたんだよね。

Come to think of it, that Shure company was originally actively developing piezoelectric devices, wasn’t it?

Shure Brothers 社は、圧電素子関連の特許を持つ Brush Development と協力して、1933年にOEM用のクリスタルカートリッジを製造、1935年には Model 70 / 71 クリスタルマイクをラインアップに追加、その後も戦前は圧電式装置を製品ラインアップのメインにしていたみたいだね。

Yes. The Shure Brothers Company, in cooperation with Brush Development, which held patents related to piezoelectric elements, produced crystal cartridges for OEM use in 1933, added the Model 70 / 71 crystal microphones to its lineup in 1935. Shure continued to make piezoelectric devices a main part of its product lineup during the prewar period.

圧電式ピックアップは定振幅特性であり、ターンオーバーより下は定振幅記録、ターンオーバーより上は定速度記録、および高域プリエンファシス、という通常のディスク録音特性とは異なる。しかし、マグネットカートリッジより出力電圧が非常に大きく、かつ再生イコライザなしで(あるいはほんの少しの補正回路だけで)「そこそこいい感じで」再生されるため、廉価なこともあり非常に重宝された( Pt.7 セクション 7.1.4)。

Piezoelectric pickups have constant amplitude characteristics, which is different from the usual disc recording characteristics of “constant amplitude below turnover frequency, constant velocity above turnover, plus high-frequency pre-emphasis”. However, the output voltage is much higher than that of magnet cartridges, and the playback is “reasonably good and acceptable” without a playback equalizer (or with only a little correction circuitry), so they were very useful due to their low price ( Pt.7 Section 7.1.4).

圧電素子ブームも後押しし、一時期は圧電式カッターヘッドも登場するなど、レコードの記録再生特性を全周波数帯域で定振幅にする、という提案が一部で試みられた( Pt.7 セクション 7.1.4)。

The piezoelectric element boom also encouraged the appearance of piezoelectric cutterheads, and for a while, some companies tried to propose that the recording and playback characteristics of records be constant amplitude over the entire frequency range ( Pt.7 Section 7.1.4).

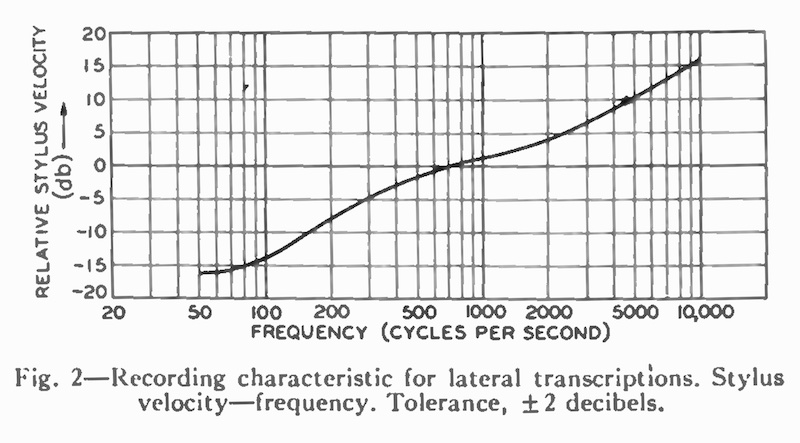

つまり、これが圧電式カッターヘッドの理想的な記録特性で…

So, below is the ideal recording characteristics of the piezo-electric cutterhead…

source: “Sound recording and reproducing system”, US Patent 2,139,916, by Stuart W. Seeley.

定振幅 (constant amplitude) で盤に記録する際の周波数特性グラフ

この特性で記録された盤を圧電式ピックアップで再生するとフラットレスポンスになる

Frequency response of the disc recorded with constant amplitude characteristic

そう、そしてこれが圧電式ピックアップの再生特性だね。

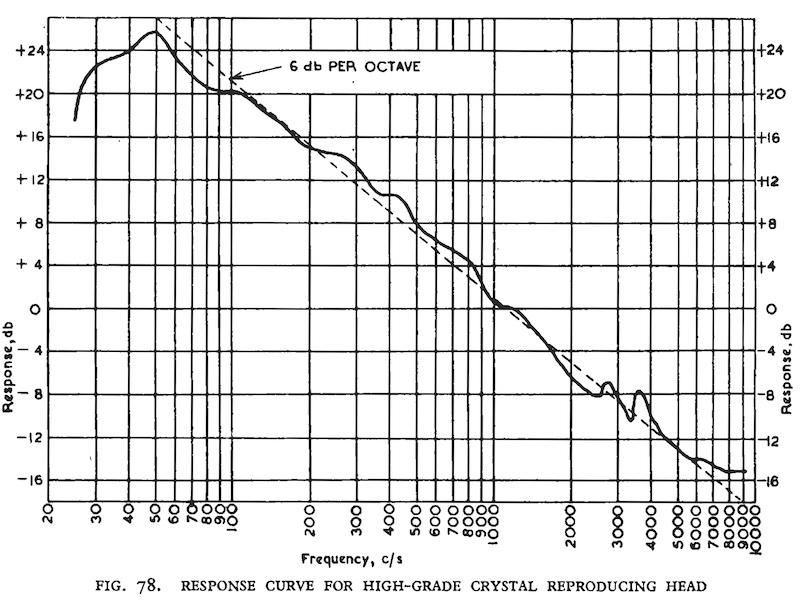

And below is the reproducing characteristics of the piezo-electric pickup.

source: “BBC Recording Training Manual”, 1953, p.89.

1950年発行のBBC社員向けトレーニングマニュアルに掲載された、高性能クリスタルピックアップの再生特性

しかし、圧電式ピックアップが温度・湿度変化に弱いこと、全周波数帯域で定振幅にすると高域増幅が過剰になりすぎてカッティング時の問題が多いことなど( Pt.7 セクション 7.1.5)から、最終的には「廉価な再生装置」としての地位に落ち着き、1930〜1970年代の一般リスナーのシステムで大いに普及した。

However, because piezoelectric pickups are susceptible to changes in temperature and humidity, and because constant amplitude over the entire frequency range causes excessive high-frequency amplification and many problems during cutting ( Pt.7 Section 7.1.5), piezoelectric pickups eventually settled on their position as “low-cost reproduction equipment” and became very popular in general listening systems from the 1930s through the 1970s.

放送局などのプロフェッショナルユースやハイファイマニア、そういったシリアスなユーザ以外の一般リスナーの間では、クリスタルカートリッジ/セラミックカートリッジなどの圧電式ピックアップが長らく主流だったんだね。

Aside from professional users such as broadcasting stations and serious users such as Hi-Fi enthusiasts, piezo-electric pickups (crystal/ceramic cartridges) have long been the mainstream among casual general listeners.

そうだね。なによりマグネットピックアップに比べて出力が非常に大きいし、そのままライン入力できる(あるいはごく簡単な補正回路をはさむだけで済む)から、一般リスナー向けに廉価な再生機器を提供できるからね。

That’s right. Compared to magnetic pickups, its output voltage is much higher, and its output can be directly connected into the line input (or with a very simple compensation circuit), making it possible to provide inexpensive playback equipment for general listeners.

なるほどね。正確な再生特性にはならないけど、フォノイコなしで「そこそこ」再生できる、ってのは当時の大半のリスナーにとっては十分ってことだね。

I see. it doesn’t have exact reproducing characteristics, but it can reproduce “reasonably well” without a phono compensation circuit, which is good enough for most listeners at that time.

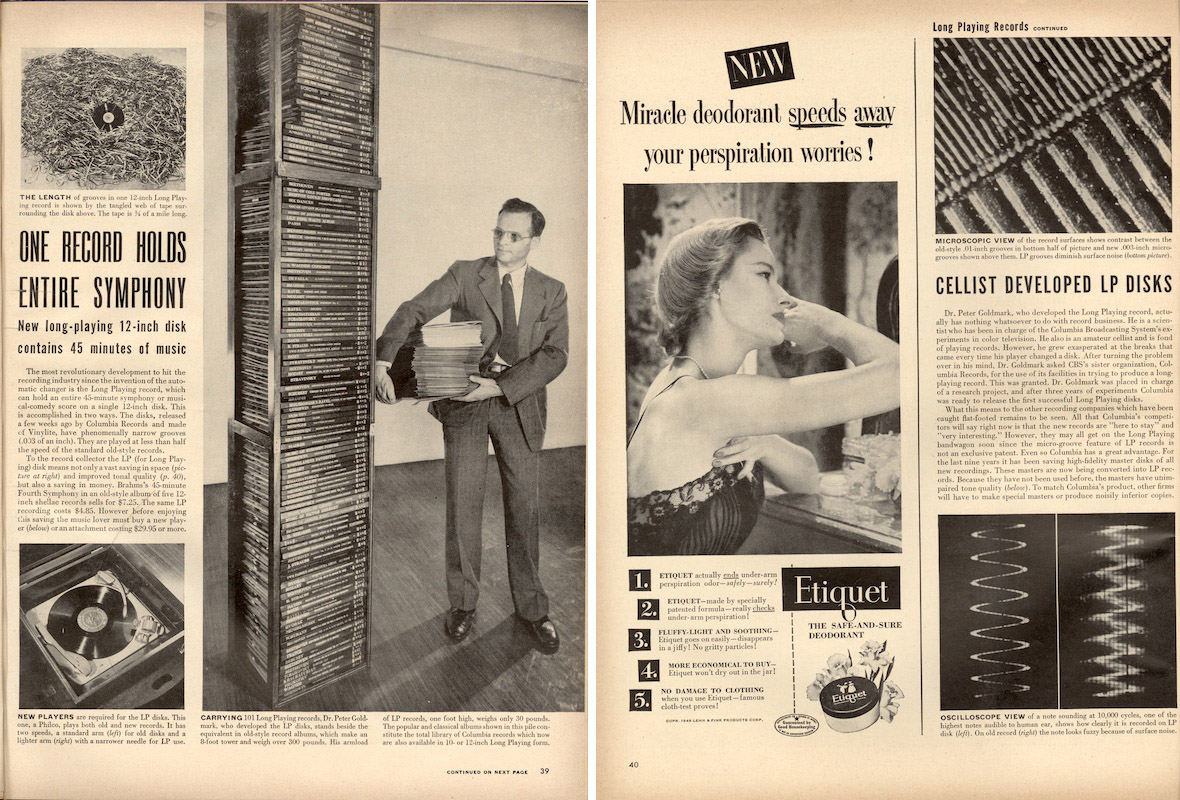

そういえば、1948年6月18日、Columbia がマイクログルーヴLPレコードを世界初お目見えした際、同時発表された世界初のLPプレーヤ、Philco M-15 Album-Length Record Player にも、圧電式クリスタルカートリッジが装着されていたんだ( Pt.11 セクション 11.1.3)。なんとその Philco M-15 のデッドストック新品と全付属品 を紹介する動画が YouTube にあるね。

By the way, the Philco M-15 Album-Length Record Player, the world’s first LP player, was also equipped with a piezoelectric crystal pickup. It was unvailed at the same time when the Columbia introduced the Long Playing Microgroove Record for the first time on June 18, 1948 ( Pt.11 Section 11.1.3). Surprisingly, there’s a YouTube video introducing a new old stock of Philco M-15 Player.

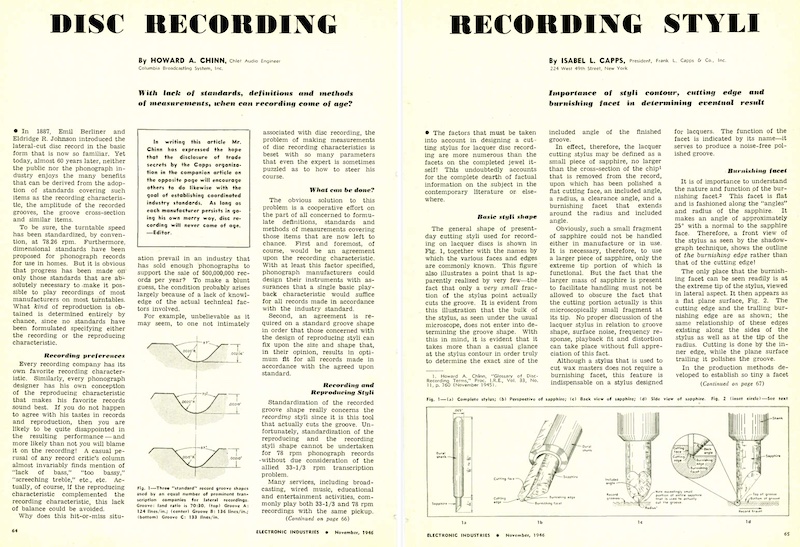

25.6 NAB Standards (1942) and Sapphire Club in the WWII Era

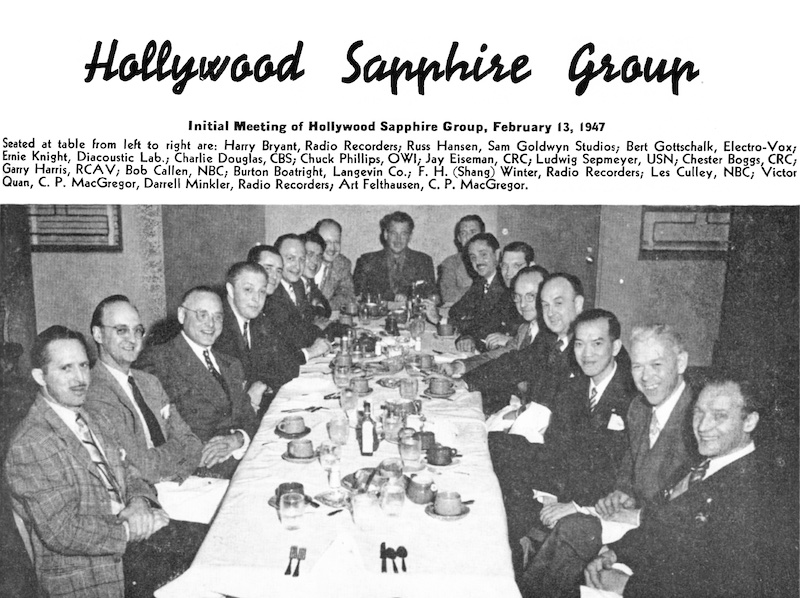

1939年頃から議論が行われ、放送局用トランスクリプション盤専用とはいえ、米国で初めてディスク録音カーブを含む標準規格が NAB によって1942年5月に策定された流れ、そして同時に第二次世界大戦中、民生用レコードの方でも、企業やレーベルの壁を超えて技術協力体制が整い出していった流れについて。1940年代前半、第二次世界大戦前後の話です。

This section deals with the trend that began around 1939, when the first U.S. Standard including disc recording curve was established by NAB in May 1942, even though it was only for bradcast transcription discs. And also the trend during the World War II, technical cooperation among companies and labels began to develop in the field of consumer records. The timespan is approximately in the early 1940s, before and after the World War II.

25.6.1 NAB Standards (1942/1949) for Transcription Discs

横振動トランスクリプション盤の録音特性がバラバラであることでラジオ局は大変な苦労をしていたため、規格標準化が求められていた。

Radio stations were experiencing great difficulties due to the disparate recording characteristics of lateral transcription records, and tehre was a need for standardization.

そこで NAB (National Association of Broadcasters, 全米放送事業者協会)が主体となって、ディスク録音技術の標準化のため、技術調査・検討委員会が複数構成され、1941年〜1942年に度重なる会合で議論が行われていたことが、当時の機関誌 NAB Reports の記事で確認できる( Pt.8 全体)。この議論には、放送局、レーベル、スタジオ、機器製造メーカなど、幅広いメンバ(1941年8月時点で58名)が参加していた( Pt.8 セクション 8.1.5)。

The National Association of Broadcasters (NAB) took the lead in forming a number of technical research and study committees to standardize disc recording technology, and repeated meetings were held from 1941 to 1942 to discuss the issue, as confirmed in an article in NAB Reports, the journal of the time ( Pt.8). The discussions were attended by a wide range of engineers (58 as of August 1941) from related industries, including broadcasters, labels, studios, and equipment manufacturers ( Pt.8 Section 8.1.5).

プロフェッショナル用途のトランスクリプション盤の世界でも、当初は記録特性の混乱があったんだね。

Even in the world of transcription discs for professional use, there was some confusion about recording characteristics in the beginning!

1941年、NAB が全米の放送局にアンケートをとった結果、最大10種類の再生イコライザ設定が必要とされていることが判明した(これでも対応が不十分)、って報告されているね( Pt.8 セクション 8.1.2)。とはいえ先述の通り、縦振動トランスクリプション盤の録音再生特性は1種類だったんだけど。

In 1941, it was reported that NAB surveyed broadcasters across the U.S. and found that up to 10 different reproducing equalizer settings were required (which still wasn’t enough) ( Pt.8 Section 8.1.2), while there was one recording / reproducing characteristic for the vertical transcription records though, as mentioned earlier.

NAB Reports の報告を時系列に追っていくと、業界に広くアンケートをとり( Pt.8 セクション 8.1.4)、専門的な技術研究者によって議論が行われ( Pt.8 セクション 8.1.9)、各企業の思惑やこだわりを超えて、放送業界一体となって民主的に標準規格化作業が行われたことが確認できる( Pt.8 セクション 8.1.13)。

Following the chronological order of the NAB Reports article, it can be confirmed that the industry was widely surveyed ( Pt.8 Section 8.1.4), that discussions were held by specialized technical researchers ( Pt.8 Section 8.1.9), and that the standardization work was conducted democratically by the broadcast industry as a whole, transcending the agendas and concerns of individual companies ( Pt.8 Section 8.1.13).

ちょうど第二次世界大戦に突入し、米国でも戦時研究が優先されるようになったため、全項目の議論と策定は戦後にまわすこととして、最低限必須とみなされた16項目が急ぎ1942年5月頃に 1942 NAB 標準規格 として策定され、1942年8月発行の IRE(Institude of Radio Engineers, 無線学会)論文誌に掲載された( Pt.8 セクション 8.1.13)。その後、戦時中は委員会審議が中断していた( Pt.8 セクション 8.1.11)。

With the entry into World War II, wartime research became a priority in the U.S., so the discussion and formulation of all items were postponed until after the war, and the minimum 16 items deemed essential were hastily formulated into a standard around May 1942. The 1942 NAB Standards was published in the August 1942 issue of the Institute of Radio Engineers (IRE) Journal ( Pt.8 Section 8.1.13). Subsequently, committee deliberation were suspended during the war ( Pt.8 Section 8.1.11).

録音特性の標準化は議論伯仲したが、どのように伯仲したかの記録は公になっていない。ともあれ、結果として、RCA Victor / NBC の Orthacoustic が横振動盤用に、Bell Labs / Western Electric の特性が縦振動盤用に、それぞれ採用された( Pt.8 セクション 8.2)。ただし、録音特性は、周波数グラフプロットのみの提示で、細かいパラメータなどは何も記載されていない。

The standardization of recording characteristics was a contentious issue, but there is no public record of how it was resolved. As a result, RCA Victor / NBC’s Orthacoustic was adopted for lateral discs, and Bell Labs / Western Electric’s characteristics was adopted for vertical discs ( Pt.8 Section 8.2). However, the recording characteristics are presented only as frequency graph plots, with no detailed parameters or anything else.

録音特性はグラフプロットのみでの提示だったんだ。

Recording characteristics were presented only as a graph plot!

source: “Recording and Reproducing Standards”, Proceedings of the I.R.E., August 1942, Vol.30, No.8, pp.355-356

1942年NAB録音・再生標準規格の第13項目として定義された、横振動用録音周波数特性グラフ

推奨回路図とかも公式には公開されていなかったから、当時の現場のエンジニアは、グラフとにらめっこしながら、実現する回路を考えたりしていたのかもしれないね。

Recommended schematics were not officially published, so engineers in the field at that time were probably staring at graphs while trying to figure out the circuits to be realized.

第二次大戦後、標準化の作業が再開し、1949年4月に 1949 NAB 標準規格 が承認されたが、当時急速に普及していたテープ機器(下の セクション 25.7.2 も参照)に関する規格策定が優先されたため、ディスク録音再生規格については1942年版を踏襲するものであった( Pt.10 全体)。

After World War II, standardization work resumed, and in April 1949, 1949 NAB Standards was approved. Because priority was given to the development of standards for tape equipment (which was rapidly becoming popular at the time) (see also: Section 25.7.2 far below), and the disc recording and reproducing standards adhered fundamentally to those of the 1942 version ( Pt.10).

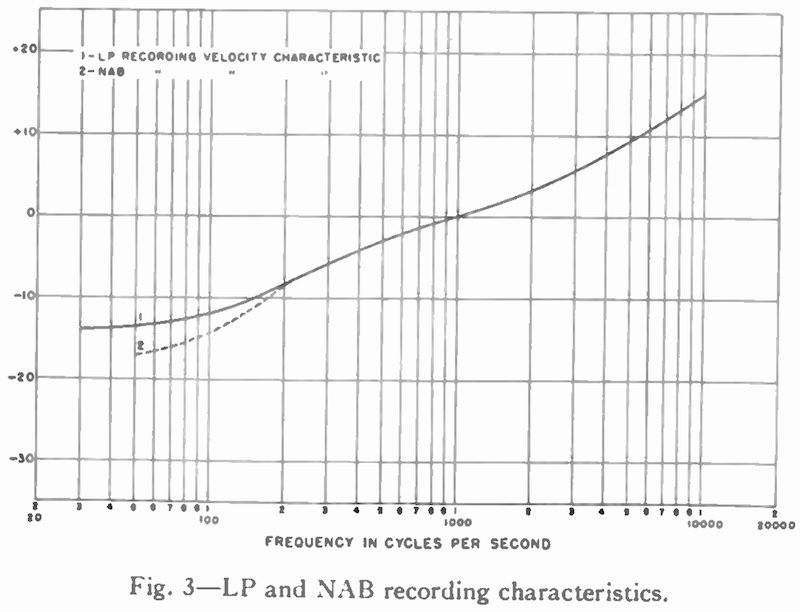

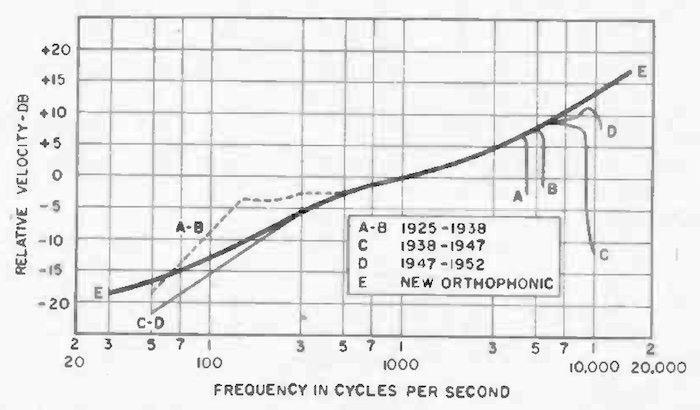

ただし、この作業の過程で、100μsの高域プリエンファシスが強すぎトレーシング歪や高域歪が増加しているから、せめて米国FM放送と同じ75μsに下げるべきだ、という意見が多くのエンジニアや研究者から盛んに出されていたことは特筆すべき点である( Pt.10 セクション 10.1.3 その他)。この議論のおかげで、のちの1953年 NARTB (NAB の当時の名称) 標準規格において、75μsプリエンファシスに変更されたという経緯がある。

It should be noted, however, that during the process of this work, many engineers and researchers actively voiced the opinion that the high-frequency pre-emphasis of 100μs was too strong and increased tracing distortion and high-frequency distorton, and that it should be lowered to 75μs, the same as that of U.S. FM broadcasting ( Pt.10 Section 10.1.3, etc.). Thanks to the debate, the 75μs pre-emphasis was later adopted in the 1953 NARTB (the then name of NAB) Standards.

この「100μsは過剰である」という意見が多数出されていた、ってのは、今回の歴史探究の大きな収穫のひとつだったね。

This “100μs is excessive” opinion that was expressed by many were one of the major takeaways from our historical exploration.

そうだね。ステレオLP時代でも Columbia LP カーブでカッティングされていた、なんてことはありえない、ってことを裏付ける情報とも言えるね。

Yes, I agree. I think this information confirms that fact that it is impossible that the LPs were cut with Columbia LP curve even in the stereo LP era.

ちなみに、1942/1949 NAB 標準規格では、定義された周波数帯域は後年より狭かったんだよね。

By the way, in the 1942/1949 Standards, the frequency range defined were narrower than in later years.

この頃はまだ 50Hz〜10,000Hz の定義域だったね。1951 AES / 1953 NARTB / 1954 新 AES / 1954 RIAA では 30Hz〜15,000Hz まで拡大された。

At that time, the definition range was still 50Hz to 10,000Hz, while the 1951 AES / 1953 NARTB / 1954 New AES / 1954 RIAA expanded the range to 30Hz to 15,000Hz.

当時はまだホットスタイラス方式のカッターが存在せず、線速度の遅い33⅓回転では内周で高域が十分にカッティングできなかったため、100μsという強めの高域プリエンファシスをかけていた、という事情もあった。そのため、カッターヘッドが内周に向かえば向かうほど、高域プリエンファシスをさらに強くかける、という自動補正イコライザ(Automatic Diameter Equalizer)も一般的に使用されていた( Pt.17 セクション 17.3.3 コラム)。

At that time, hot stylus cutters did not yet exist, and the slow 33⅓rpm linear velocity did not allow for sufficient high-frequency cutting on the inner circumference, so a strong high-frequency pre-emphasis of 100μs was applied. Therefore, an Automatic Diameter Equalizer was also commonly used, which applied a stronger high-frequency pre-emphasis as the cutterhead moved toward the inner circumference ( Pt.17 Section 17.3.3 Column).

その「ホットスタイラス」方式ってのは?

What’s that “hot stylus” method?

その名の通り、スタイラス、つまりカッター針を電熱線で加熱しながらカッティングする方法のことだね。バニシングファセットのないカッター針でラッカー盤にカッティングするとS/N比がとても悪くなる、しかしバニシングファセットありにすると高域損失が増大してしまう。当時のエンジニアはこのジレンマに悩まされていたんだけど、ホットスタイラス方式だとS/N比劣化と高域損失を共に抑制できる。これに気付いた Columbia の William S. Bachman 氏が LP カッティングに採用したんだ。そしてこの方式がマイクログルーヴ時代の一般的なプラクティスになった、というわけだね。

As the name suggests, it is a method of cutting while heating the cutting stylus with an electric heating wire. Cutting a lacquer disc with a cutter needle without burniching facet results in a very poor signal-to-noise ratio, but with a burnishing facet, the loss of high-frequency increases. Engineers at that time were troubled by this dilemma, but with the hot stylus method, both the S/N ratio deterioration and the loss of high-frequency could be suppressed. William S. Bachman of Columbia Records realized this and adopted this method for LP cutting. This method then became a common practice in the microgroove era.

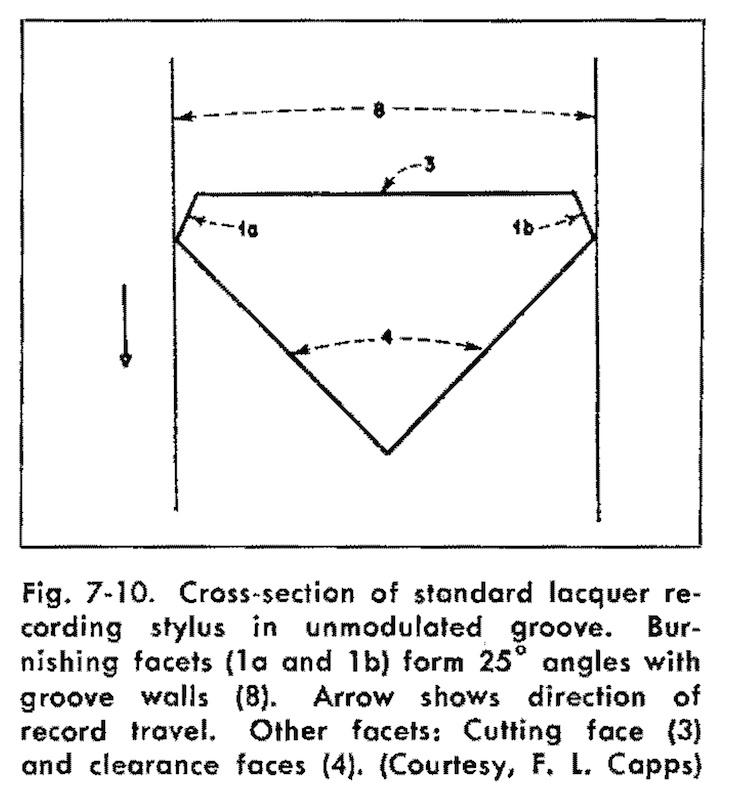

ふむ、下の図の 1a と 1b の部分がバニシングファセットか。

Hmm, the 1a and 1b in the figure below are burnishing facets.

source: “The Recording and Reproduction of Sound”, Oliver Read, 2nd Edition, 1952, p.113

バニシングファセットがないと、ラッカー盤とカッター針の抵抗が大きすぎて、カットされた溝の側壁がザラつき、S/N比が低下する。かといってバニシングファセットを広くしすぎると、細かい溝が刻みにくい、すなわち高域が十分にカッティングできなくなる。このバランスをとるのが難しかったということだね。ホットスタイラス方式が実現してからは、バニシングファセットを最小にしても S/N比を高くとれ、同時に高域まで微細にカッティングできるようになったんだ。

Without a burnishing facet, the resistance between the lacquer disc and the cutter needle is too great, causing the sidewalls of the cut grooves to be rough and lowering the signal-to-noise ratio. On the other hand, if the burnishing facet is made too wide, it is difficult to cut fine grooves, i.e. the high-frequency range cannot be cut sufficiently. It was difficult to strike a balance between the two. After the hot stylus method was realized, it became possible to achieve a high S/N ratio even with a minimum burnishing facet, and at the same time, it became possible to cut high frequencies in fine increments.

25.6.2 Sapphire Group

第二次世界大戦中、米国では多くの原材料が軍需優先物質となり、レコード業界も影響を受けていた。また、レコードの重要な原材料であるシェラックは、東南アジアや南アジアが主たる原産地であり、大戦中日本が進出していたため、シェラック不足の危機が訪れた( Pt.16 セクション 16.2.1)。これにより、シェラックの代替となる合成樹脂の開発が加速し、戦後のポリ塩化ビニル製レコードが実現した側面もある。